AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Katango

Eversden and Robinson had emigrated with their families from the UK in the 1970s, the Eversdens from London, and the Robinsons from the Merseyside city of Birkenhead – home to Elvis Costello, synth-pop architects Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, and their friendship’s prerequisite, Echo and the Bunnymen. Robinson had returned there for the summer holidays the previous year, and an encouraging older cousin smuggled the bright-eyed 16-year-old into Liverpool’s clubs to see XTC and A Certain Ratio. He bought and brought home to New Zealand every new record he could.

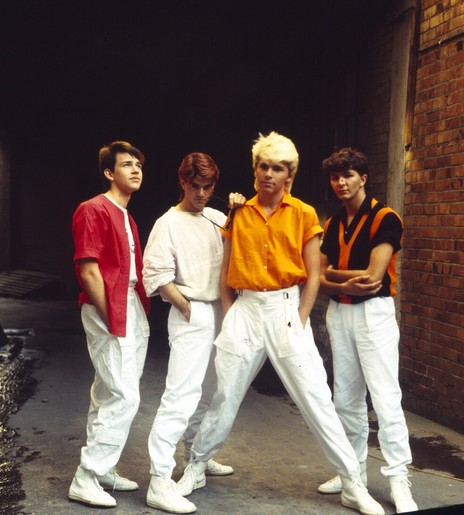

Back in New Zealand, the lads were surrounded at school by utter disinterest in English New Wave; reggae and authentic rock were the thing. Disco sucked, sure, but then what was there to dance to? Sharing precious slabs of Depeche Mode, The Human League, Ultravox and Duran Duran, new best mates and nascent new romantics Eversden and Robinson would deck out in op-shop suits, hop on a trail bike and sneak into city gigs to see bands including Blam Blam Blam, The Newmatics and The Screaming Meemees. Three-month-old NMEs – the latest copies available – were their style guides. The first Duran Duran album cover taught them how to dress, with Eversden sporting a Nick Rhodes doppelgänger bouffant.

They had the look, the inclination toward extroversion and the DIY attitude. Why not start their own band?

So: they had the look, the inclination toward extroversion and the DIY attitude. Why not start their own band, and make the music they liked? Duran Duran famously claimed to base their beginnings on an unlikely mating of the Sex Pistols and Chic, and Robinson concurred, “Keyboards and keyboard programming seemed to be the answer to punk of its time, and punk in 75-76 was all about ‘just do it.’”

Eversden agrees. “[Carl] saw me being a bit of a showoff and dancing around and thought, ‘Well this guy can sing’ and it was his idea to put the band together. Synth music had that punk attitude – you didn’t really need to know how to play, you just needed to have a synthesiser and a few machines and you could get out there and do something – it wasn’t about musicianship, it was about endeavour. We saw these guys standing on stage with their fingers on a keyboard, and they didn’t look like they could play – and we thought, ‘well, shit we can do that.’”

Depeche Mode was an even bigger influence, with no bass player or drummer on stage – only man and machine. Except that so far, these men had no machines – and no experience making music.

Robinson had started at university, where he soon met Richard Newcomb, who was into the same kind of music. He had a keyboard, a drum kit, a room to practise in – and, most importantly, he knew what he was doing. “So that encouraged us to start jamming and the three of us started trying to do stuff,” he says. “Until Richard came along we weren’t doing anything, we didn’t own any bits and pieces. I’m sure we wanted to do it but the actual physical band appeared when Richard came along.”

It was a brilliant beginning, Eversden remembers. “When we first started … we were just these kids that loved dancing and music. The three of us became like the Three Musketeers of Pop Music. Everyone used to like to dress up like Heaven 17 in old suits and things – running up Queen Street, sliding on our winklepickers into places and dancing around and singing.”

Robinson and his girlfriend had a second-hand clothes stall at Cook Street Market in central Auckland. “We would go around the country buying old ’50s shirts and classic suits and sell them, basically to people who were then dancing in the clubs we went to. So that’s where we got lots of our clothes from.” Their stall afforded them both the look and the sound, courtesy of Robinson’s agreeable partner. “I convinced her that she should buy us a drum machine, so she bought us a [E-mu] Drumulator, which was like a thousand dollars! Which was a fortune! It was like buying a Rolls Royce. She never quite forgave me.”

Through hire purchase, student bursaries – and generous girlfriends – they soon had a fully electronic setup.

The trio hung out at a music shop in central Auckland where employees Nigel Russell (Car Crash Set, Danse Macabre, The Spelling Mistakes) and Greg Mackenzie (The Normal Ambition) would chat about new bands and let them play with the machines that they couldn’t afford. But through hire purchase, student bursaries – and generous girlfriends – they soon had a fully electronic setup with lead, bass, and drum synths.

Newcomb led the way, writing the music and encouraging Eversden and Robinson to learn their parts. He wrote the music to their first single, ‘Pop Boys’, sitting in his room at home. He played the song over the phone to Eversden, who then wrote the lyrics. “We were so impressed with Richard,” says Eversden. “Here we were with our little thumbs and fingers just holding down bass notes and letting the machines do everything – and he could actually play!”

And they were just on the verge of making the scene, Eversden remembers. “We were all kids from the suburbs, and there was nothing to do there but get drunk and cause mayhem, and when we discovered this place called A Certain Bar we used to go there every weekend and listen to the music.”

On the corner of Wellesley and Albert streets in Auckland’s CBD, A Certain Bar was Peter Urlich and Mark Phillips’s first club. There, the young lads could hear otherwise undistributed new music that a slightly older generation were importing. Phillips became their first manager – and they moved from just dancing to playing music to dance to.

They weren’t yet Katango, though: the trio was originally called the Entebbe Rebels, a roughneck, rockist name referencing a heroic Ugandan hijacking rescue. “It sounded pretty cool, it sounded pretty punk,” says Robinson. Their tag “Katango” was in fact just an invented word. It sounded poppy and dance-y, like a Batman sound effect, in the primary colours and halftone dots of a Lichtenstein painting – very ’80s and technicolor and fun, rhythmic with an electric twang.

The first Entebbe Rebels gig was with the Diehards at the Pakuranga Yacht Club. Robinson: “It was a very typical Diehards gig, they got completely drunk and fell backwards through the drum kit and smashed everything up so … perfect rock and roll! We were terrible of course, but it didn’t matter because we were dressed funny and had funny hair and girls all thought we were weird so that’s good.”

Another time, another yacht club – Bucklands Beach this time – another drunken Diehard: “One of the Diehard members sabotaged us – we had one lead going – and he pulled the plug and everything just went dead.” Playing to an audience of friends, Eversden just “swore at him and got them to plug it back in again, and started back up again! That was a lesson we learnt, that we were totally dependent on these machines.”

Eversden was learning to bring his swagger to the stage – but to throttle it too. “I thought I was a bit invincible, and I had all this confidence. And so, we would get on stage, and we’d jump around and sing … sometimes it would be quite embarrassing because we’d be jumping around and the machines would break down and we’d have to sort of bluff our way into the next song!”

“Sometimes it would be quite embarrassing because we’d be jumping around and the machines would break down.”

Not that they were alone in this fragile new electronic landscape, as Robinson remembers. “We always had technical issues but I think everyone did. I remember going to see New Order at Mainstreet, and they had a Drumulator and an Emulator, and for some reason they just didn’t want to talk to each other that night. One was stopping, one was starting and the whole gig was completely ruined, that was it! That was the way it was and there was no backup.”

Katango played a few gigs as a threesome, and got a bit of notice supporting other bands playing the North Shore, but before long the talented Newcomb was poached by Paul Agar for his new band, Marginal Era. Eversden: “When we lost Richard, we thought it was the end of the world, but then Steven and Andrew came along, and that was another twist.”

Newcomb gracefully introduced two ex-schoolmates from Auckland Grammar, boffins Steven Glaister and Andrew Milne. They were a couple years younger but crucially added Roland drum machines and a bass synth, from their band called Honesty Box – which just so happened to need a vocalist and synth player – so the two bands fused. Eversden and Robinson brought their Roland SH-101, TR-606, and Juno 60, and Glaister slipped into Newcomb’s role as principal songwriter.

They were glad to add the new machinery, and they squeezed the most out of it, as Eversden describes: “When we first got the 303 [Roland TB-303 Bass Line Synthesiser, with memory storage for seven songs] we wanted to do more songs. So there was this guy we used to go to and we’d open up the back and take the chips out and he’d piggy-back the memory chips on top. He put a switch into it, and it was a Kiwi cheap way of putting more memory in them!”

Honesty Box was a school hobby band, and the two new guys were both quite shy, but they had some interesting songs and it was clear that Glaister was a clever songwriter and skilled performer. Eversden and Robinson brought four or five songs from the Newcomb era, but Glaister was now the main composer. “We all wrote together but Steven was the primary keyboard writer. We’d write lyrics on top of music Steven had come up with, or Steven would come up with half a song and then I’d work a bass line around it. We’d add stuff to it [and] spend a lot of time practising.”

They could no longer use Newcomb’s practice room, but Eversden’s sister had gone back to England so there was a spare bedroom at his house. There, remembers Robinson, “we bothered his parents for as long as they would put up with it, then moved to my house and bothered my parents for as long as they’d put up with it.” The band eventually shifting to a proper practice space when they could afford it.

Robinson’s supportive and deep-pocketed girlfriend not only ran the fan club and bought them gear, she also introduced them to her ex-boyfriend Russell Crowe, an Auckland scenester who chewed the scenery at an underage club he had called The Venue. Eversden remembers that the future gladiator would sit “in the back room with his cowboy boots up, leaning back on his chair like somebody out of a movie.” Crowe had his own band, [Russ le Roq and the] Roman Antix, who “used to do their own graffiti around Khyber Pass Road,” banking on band vandalism and Crowe’s ambition for their self-promotion.

the teens at Russell Crowe’s club loved KATANGO’S ELECTRONIC POP.

As soon as they could, they played originals exclusively, though Eversden remembers playing a cover – of The Human League’s cover – of ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’ at The Venue a couple of times. “We loved it so much, and it’s really simple because it’s in the key of C – you just hit the white notes on the keyboard. I used to try to sing it like Phil [Oakey] did!”

Auckland’s adult audiences didn’t yet exactly back Katango’s brand of electronic pop, but the teens at Russell Crowe’s club loved it. “We would play with Graham Brazier or someone like that,” says Robinson, “and people thought we were crap and booed because we weren’t rock and roll, and we wore make-up and dressed funny. So the normal places where everyone was going to watch gigs were very much rock and roll based, there was nowhere to play. Schools or school balls or school gigs – or The Venue. The Venue was kind of a blessing because there was an underage audience and they loved us because we were kind of pretty boys if you like, interested in fashion.”

Katango played Crowe’s club two or three times a week, wrote more songs, tightened up their live act – and soon they had a record deal. “That’s where we got picked up. [Nick Morgan] worked at Harlequin Studios as an engineer … and then at night he was doing the desk at The Venue.”

Zulu Records was set up as a sub-label of Doug Rogers’ Harlequin Studios to record their “second” bands in the downtime. The label was distributed by CBS under their “new artist” series. “It was an interesting time in New Zealand because the international people like CBS were getting a hard time for not recording, not supporting local talent,” Robinson recalls. Some New Zealand radio stations were upping their local content, “and the record companies, to look good, would do a few little runs of New Zealand bands. It was good for us – we were lucky.”

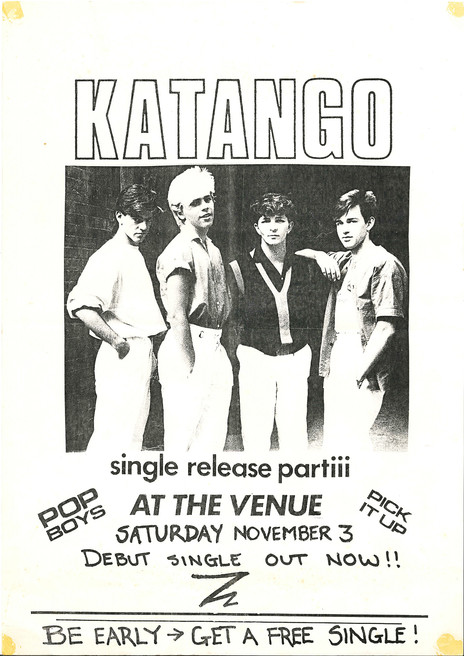

Their first 7" for Zulu, 1984’s ‘Pop Boys’ b/w ‘Pick It Up’ was a manifesto in both form and content, one of a tiny handful of all-electronic pop records from early ’80s New Zealand, featuring songs written by Eversden with both the departed Newcomb and new guy Glaister. A-side ‘Pop Boys’ was their policy statement, steeped in the sunshine cast by ‘Just Can’t Get Enough’ by their heroes Depeche Mode. It was bubbly and upbeat, pure and playful, sunny and simple – both the definition of pure synthpop and a naive notification of intent, echoing the ’80s existential employment angst of both The Body Electric’s ‘Dreaming In A Life’ and The Scavengers’ ‘Mysterex’:

Wake up,

It’s time to earn a living.

Make your daily bread,

Get up, get out of bed.

Monday,

The week is just beginning.

Another day, another dollar,

White boy, white collar.

Pop Boys, Pop Boys,

Waiting to be found.

Pop Boys, Pop Boys,

Looking for a sound.

I don’t

Wanna be a nine-to-fiver.

It’s a life I dread,

I’ll be a Pop Boy instead.

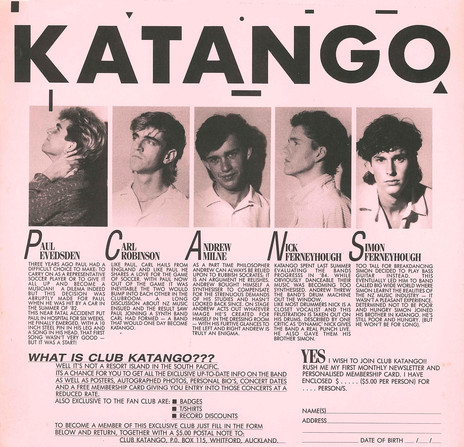

It’s a wee bit starry-eyed, as the reviewer noted in Rip It Up, “Katango would like to be on the cover of Smash Hits and that’s kind of a nice ambition in a way,” though they also wrote that the A-side wouldn’t get them there. The ever-modest band agreed, with Eversden noting in his bio on the insert to their next release, “that first song wasn’t very good – but it was a start!”

B-side ‘Pick It Up’ has a more of a kinetic glow – it makes your pants itch for the dance floor. Rip It Up’s reviewer approved, writing “well-executed, with just the right sprinkling of pretension, it actually communicates something youthful in its grooves – and that’s important, no?” Glaister wrote the music and most of the words for ‘Pick It Up’ but Eversden penned the rap at the end, inspired by Wham!’s early single ‘Young Guns (Go For It)’.

on TV’s Shazam, Eversden was soft-spoken and self-effacing

After the release of the first single, they began to show up on afternoon telly, with front man Eversden ever soft-spoken and self-effacing in their Shazam interviews. “If you wanted to be on TV you had to try to get on these bloody things,”, he groans.

They were on Shazam! at least four times, performing live – or “live”, rather – miming along to the tape for an audience of 9-12 year olds. “It was a bit weird, really,” Eversden laughs. Host Phillip Schofield remarked that “they hit it on the nose” with their “blatantly commercial sound,” which most bands would shy away from. Eversden explained that it was just the start: “there’s not enough people for you to become a cult band,” so they’d “give the public what they want, see that we’re good songwriters, then we can develop from there, y’know?”

Their instincts were good: in 1984, they won the Shure Golden Microphone Best New Band competition (The rest of the top five was: #2 – You’re A Movie, #3 – Car Crash Set, #4 – Marching Orders, #5 – Blasé).

Girls loved this cute, trendy energetic band, with Rip It Up’s Jeremy Templer painting Katango as “potential pin-ups playing synthesiser pop” at a gig at The Venue, as they packed the dance floor (after quashing the ubiquitous technical issues). “The idea of being on stage when you’re a keyboard band – visually there’s not much to look at, so Paul would dance around like an idiot, and I played the bass keyboard,” says Robinson. “I could move around with the 101 [the SH-101, which could be held like a guitar] – which was at least something to look at – with the other two grinding away in the background with keyboards that did or didn’t work.” Eversden elaborates: “When we used to go out dancing, we’d sort of take over the dance floor … we thought we were a bit indestructible, y’know? So when you saw us on stage, that was really just Carl and I playing out this thing.”

And then they started playing out all over the place. Hanging out at Harlequin and The Venue, they rubbed shoulders with older, established musicians such as Dave McArtney, who gave them advice, helped out on recordings, and got them gigs.

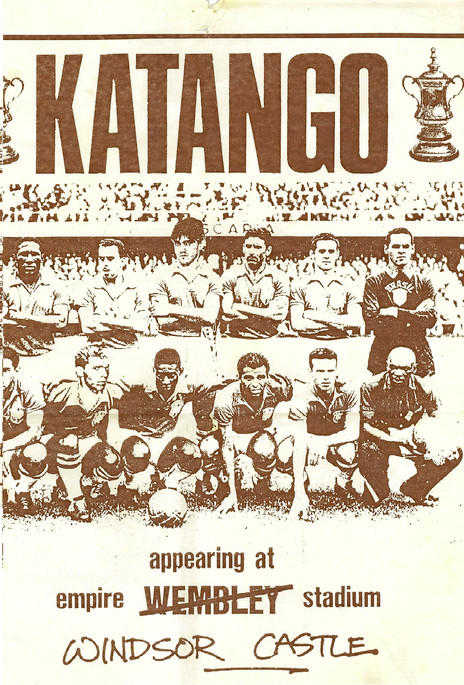

Robinson: “We started playing at places that we loved, places like the Windsor Castle and The Gluepot, where we’d been as kids, so it was heaven.”

1985 marked the biggest year for Katango, and also the beginning of the end.

After playing support for other unknowns for so long, they started playing with other bands “that were more our ilk like The Mockers and those kinds of bands of the ‘next generation’, Jordan Luck … the Meemees … people like The Body Electric who were more our style.”

1985 marked the biggest year for Katango, and also the beginning of the end. They would soon have a new line-up, a new record, a whole swag of high profile gigs – and make an ill-fated shift.

Glaister was over it though – Katango was taking too much time away from his studies. He enjoyed academia, later gaining a PhD and teaching philosophy at American universities. Robinson recalls that “he liked writing but he didn’t really like playing or travelling around the country, and we had travelled around the country quite a bit.”

“Carl and I thought ‘what the hell are we gonna do,’” continues Eversden, “and we sorta thought, ‘well, we better learn how to write songs!’”

They placed an advert in Rip It Up to replace Glaister. The steadfast technophiles were pre-programming more and more on their machines, Milne taking over Glaister’s parts and Robinson adding fills, “so we thought, ‘well why not get a bit more visual and add a live drummer and live bass player?’ because we’d seen bands like Tears for Fears and Nik Kershaw who were doing that, and it was something more to look at. Actually, we were only looking for a bass player, so Simon came along as a bass player and said, ‘well my little brother’s a really good drummer,’” says Robinson. “Nick was only 17,” adds Eversden. “He was so young when we started he wasn’t even allowed in pubs!” Nick and Simon Ferneyhough joined the band for the last leg of Katango’s New Zealand years.

“At one school the girls were throwing knickers on stage! Obviously, they were doing it as a joke ...”

Doing a school tour was a quick way to make some cash, tighten up and play straight to their audience. For six weeks they played lunchtime gigs around the Auckland region, drawing up to 500 kids at each. The tour included a run of 10 schools in two weeks. Eversden cringes, chuckling, “at one school the girls were throwing knickers on stage! Obviously, they were doing it as a joke – it was just a fun thing.” With his unusual last name all alone in the phone book, Eversden was plagued by besotted girls calling after these gigs.

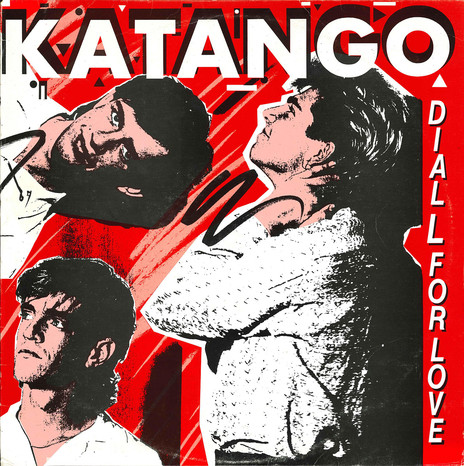

And they got to work on their next record, Dial L For Love. Though he’d left the band, Katango recorded a radio mix and an extended mix of the Glaister-penned ‘Dial L For Love’, backed with a remix of his ‘Pick It Up’. Dave McArtney produced the record and added his guitar to the mix, and the band took advantage of the newest technology. Eversden remembers: “Paul Streekstra, who engineered it, had just got this new sampler. Back in those days samplers were really new, early days. There was the Fairlight, and then Emulator came out with this sampler. It was a bit naive the way we used it because we were just so excited to be able to do that sort of thing, and one night Paul and I sampled a whole lot of things and stuck it into the record.” Sounds included ringing telephones, weird stridulating creaks – and Eversden’s vocals multiplied and played like a keyboard, drenched in reverb.

Robinson explains another necessary innovation in electronic pop. “I reckon [Nick Ferneyhough] was one of the first drummers to play to a click track in New Zealand – that was really unheard of. Because everything was programmed, he had to play with headphones to a click track to keep time.” Ferneyhough used this metronomic method in the studio and on stage, playing live like a real-life Kraftwerk robot.

At the 1985 New Zealand Music Awards, Eversden was nominated for Most Promising Male Vocalist, and Katango for Most Promising Group, losing out in both cases to Satellite Spies. They returned to Shazam! to perform ‘Dial L For Love’ which shared Shazam!’s Top Ten with Alison Moyet’s Alf, Madonna’s Like A Virgin, and Ultravox’s The Collection.

They got a big break too, supporting Nik Kershaw when he came to New Zealand on the wave of his international hit, ‘The Riddle’. “That was probably our biggest live audience,” says Robinson. “We played some of the big group concerts, and we played the last gig at Mainstreet with Graham Brazier. Mainstreet was where I had seen Siouxsie and the Banshees and New Order so for us it was heaven, it was an institution. The dressing room walls had thousands of lyrics all over, graffiti from all kinds of famous artists. I remember that we were in there smashing bits – literally taking the plaster off the wall with this graffiti all over it to take home. That seemed to be fine!”

They were just more popular than ever, playing His Majesty’s Theatre with The Mockers, and a “Super Rock” concert with Peking Man at the Christchurch Town Hall. Admittedly, their pull wasn’t just about the sounds: journalists outside the Town Hall gig quizzed girls on Katango and got quotes like “great guys … and great music,” and “I like the lead singer, personally – he’s quite nice, really!”

Katango only released three songs and a couple of remixes, but videos of two unreleased songs from the Glaister and Newcomb days (‘Brand New You’ and ‘Pretty Baby’ respectively) can be found online, recorded at the Town Hall. They recorded demos of these – and more – at Harlequin, but Zulu Records weren’t happy with them. Not poppy enough, laments Eversden. “Music was changing a bit and we wanted to change with it. I certainly didn’t want to be in a band just singing to young girls anymore. We were trying to look for a bit more creativity.”

“Things happened very, very quickly, from being ’84 Band of the Year/Golden Microphone, and then the next year Paul and I were getting really itchy feet,” says Robinson. They were making a full time living in Katango and travelling throughout New Zealand, but felt they were already thrashing against the sides of their enclosure, and they never wanted to be just a “cult band”.

“We knew we could keep going and doing what we wanted to do but it wasn’t enough,” says Robinson. “For Andrew – who was finishing his Masters – it wasn’t going to be enough for him unless it was really big. And same for the Ferneyhoughs, they were both smart kids and going through university.

“The Dance Exponents had said they were gonna crack Australia within a month [famously, on Radio With Pictures] and came back with their tails between their legs, then about six weeks later they buggered off to the UK, and then so did the Diehards.”

Robinson and Eversden thought they might have a go too – that they’d get better by being there, as well as have a much larger audience. Why not? They were both originally English, and they had an introduction from their New Zealand label head to meet with CBS UK.

The duo left for London in late 1985, bringing keyboards and sequencers, to make it big and to drink with Dance Exponents and ex-Diehards. Flashing back to a fateful first meeting on an Auckland football pitch, Robinson recalls, “we used to play soccer together at the weekends with the Screaming Meemees guys and the Dance Exponents guys and the Diehards. We all had soccer as a common love.”

They weren’t the first to find out – and won’t be the last – that it’s hard to break the UK. They had a polite meeting with CBS – who courteously offered to attend any gigs that Katango might play. Without solid representation or management, they struggled. Katango never again played a formal gig, though they spent two years writing and practising and trying to spread the word.

“IT WAS A BIT LIKE BEING A PUNK IN NEW ZEALAND BECAUSE WE WERE DIFFERENT”

And they had a blast, sighs Eversden. “We fell in love with going out so much and having fun in London that we kind of lost our way, and it didn’t really happen.” Robinson concedes. “We just kind of got hit by London, y’know? When you’re in New Zealand and you’re the best keyboard band or whatever – you get to London and there are 50 bands much better than you, and it’s tough. So we just kind of faded, I suppose.”

Robinson had separated from his new girlfriend, a Japanese major at university, when he left New Zealand. She left for Japan, then shifted back into Robinson’s life and the London flat with him and Eversden. When the lads finally let go of Katango, she and Robinson married and moved to Tokyo, where today he runs companies importing and exporting wine from around the world.

Robinson no longer plays much music. “I don’t have a keyboard. Having a music room is a bit of a luxury in Tokyo!” Being in Katango was a fun and momentous time, and it felt so fresh back then. “It was a bit like being a punk in New Zealand because we were different, we didn’t have any proper musical instruments and we wore make-up so people thought we were gay. We were so into the music, we just didn’t care, we really wanted to change New Zealand.”

Eversden turned the trip into an OE, spent a year in America on the back of a Kerouac book, landed in Sydney where he met his wife, and returned to Auckland to follow in his father’s footsteps running a lighting company for film and television. And though he’d already sung on some of the country’s biggest stages, he took singing lessons, and learned to play guitar and keyboards. “For me it was quite an inspirational time, in those days when I used to watch Steve Glaister write. It really excited me, and since then I’ve actually learned how to write songs myself.’ These days he plays with Steve Melville from Roman Antix, and also with old bandmate Newcomb.

“We saw so much music around us, everyone was so serious and they were all so insecure,” he adds, “but we just wanted to get out there and have fun. We were real pioneers in fact because we were one of the first bands around to perform without any guitars or any bass or any drums. It was just some machines, synthesisers and my voice – and me jumping around on stage.”

Shazam! Interview and 'Pick It Up'

'Dial L For Love' at Telethon 1985

'Dial L for Love' (concrete mix)

Zulu

Paul Eversden - vocals

Carl Robinson - synthesiser

Andrew Milne - synthesiser

Steve Glaister - synthesiser

Nick Ferneyhough - drums

Simon Ferneyhough - bass

Richard Newcomb - synthesiser

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air