When Christopher Columbus was on his famous voyage he kept a diary every day. Thirty-five days before he discovered America the diary was blank except for one solitary entry: “Saw no land – kept sailing.”

That just about sums up my career. Clutching at blind faith, frivolous curiosity and disciplined hedonism, I’ve been allowed to chase my addiction, and like all addictions they’re totally self-consuming.

I’m hardly role model material, not especially clever and very indulgent, but I’ve been lucky enough to get away with it. I’ve always considered myself really lucky. I’ve survived three major car accidents, flirted with lifestyles, held an appalling disregard for the future and endured some almost laughable (now) near disasters. On the other hand I’ve always had a place to call home and a total all-encompassing passion that has motivated me ... music.

Somewhere I developed a single-minded respect only for creativity. It seems like the only real truth. Oh yeah ... I also learnt early on to live really cheaply.

It took me a long time to realise that I was actually doing my career. An idea before its time has to learn to wait. The thing is that before I left for overseas it had never occurred to me that you could live from music. It just wasn’t a job, everybody said you couldn’t do that; it’s a hobby and exclusively the domain of the preordained. One of the guys from Herbs once told me of a similar experience – he went to sign on and was told that musician wasn’t an occupation.

My first band was wildly naïve, staunchly original ... And of limited ability.

I’ve taken crap jobs to do music but I’ve always done music. Which is weird really, because there was no music at home. A guy across the road turned me on to music. I‘d like to say that I instinctually sensed “cool” but that would be wildly arrogant. Whatever, I’ve always understood that music and cool go hand in hand.

I took five years to get a three year BA because I spent two years doing nothing but playing guitar. I left Auckland to go to Otago University and joined the music tribe. My first band was wildly naïve, staunchly original and hell-bent on making our sound as different to anything else around in order to disguise our limited abilities. It taught me to approach an instrument in a different way (it was too revealing to approach the orthodox way) and to actually grow within one’s own limitations.

Art for art’s sake hits for fuck’s sake – we wished. The underground is a really good place to be although one’s appreciation of the orthodox can atrophy. It’s easier to sneer at successful bands by hiding behind a credibility tag. Trouble is, I always loved pop so it was a pretty lame axiom.

When I went overseas I took a guitar but I just couldn’t connect in the UK. It just all seemed so bloody hard and you had to know the right people and I didn’t. It wasn’t until I lived in France and started playing early music (on a collection of guitars, dulcimers and psalterions) to accompany a travelling theatre group who performed Renaissance theatre around the villages of the Cote d’Azur. That catalysed and cemented my raison d’etre and I suddenly realized I was in the music biz. I was getting paid for it. For the first time, it was no longer a misdemeanor to call myself a musician. In France music is an honourable profession, like painting and prostitution, and there’s no such thing as a part time whore – big breakthrough.

I went back to London and via my neighbour, who turned me onto music in the first place, scored a job with a record company called Stiff Records. It was post-Pistols, very street, very London – it was an eye opener into the other side of music.

From my vantage point as general mail order gofer persona non-importante it meant, if nothing else, hanging out professionally with a lot of the wrong crowd. It was instant buzz material – Wreckless Eric, Ian Dury and Madness weren’t household names then but they were on their way; chaotically, charismatic people in an era that was fanned by hardcore speed, hash, lots of no sleep and that headspace that can cause permanent damage. Right place at the right time and got out in the nick of …

I moved to New York and worked for Stiff there as well. That was when bands like The Feelies and The Plasmatics were the main roster. You had to see The Plasmatics to believe them. A stripper called Wendy O. Williams was the singer, the band had fluorescent mohicans, wore tutus and travelled Manhattan subways like that, skagged out of their brains. Part of their act was to blow up cars on stage and mess about with chainsaws. Great show, shite music. New York is really only a place for the fearless, music culture and drug culture are just part of the same equation. The spare change route from Times Square to the Bowery is a tradition older than rock and roll, and all downhill.

At this point in time I had absolutely no idea what the fuck I was doing. I had to come back to Aotearoa. Imagine my delight to find that in the six years I’d been away that there was a really vibrant creative scene going on. And the bands here were great, they always have been and always will be ... physical distance has no bearing on the creative process!

It was totally refreshing to see a young Screaming Meemees, Fetus Productions, Danse Macabre, Blam Blam Blam making waves, a thriving Rip It Up, packed venues, dodging the boot boys and getting rowdy ... there was nothing like that when I left. I decided I was going to stay here and if nothing came my way then I’d check out Australia.

I still had no clue what I wanted to do for a career but I had zero responsibilities.

I eventually scammed a job as a tour manager for a while. The Pink Flamingos were still a huge band here on the live circuit but their piano player [Paul Hewson] was a very vulnerable man. I was to discreetly keep an eye on him – it’s not hard to double guess drug users.

Trevor Reekie (far right) backstage at Auckland's Town Hall with The Cure, manager Chris Parry (left), and promoter Terry Condon. - Trevor Reekie collection

This led to scoring a job working for a small independent label called Stunn Records. They licensed The Cure for New Zealand because the Stunn label owner was a good friend of ex-Fourmyula drummer Chris Parry (who managed The Cure, started Fiction Records and became a millionaire). When I came on board, Stunn had just released the 17 Seconds album and the band toured here for the first time.

One of my first impressions of The Cure was picking them up from their hotel in Parnell – an irate house manager of Italian descent was going utterly ballistic. He had to break into the band’s apartment to find that the band had had a lot of fun with some complimentary fruit, the minibar and some local escorts. Robert Smith seemed to be asleep spread-eagled over an ironing board.

Being offered studio time is like putting a narcissist in a roomful of mirrors.

Stunn also handled Australian band The Church and released their debut stuff, but for me, the real attraction was to break into the local scene and develop a roster. We set up a joint-ownership deal with Mandrill Studios and started the Reaction label. This really was my formative introduction into the creative side of producing music and through Mandrill’s generosity, I started living in studios.

Being offered studio time is like putting a narcissist in a roomful of mirrors. We recorded bands like Danse Macabre, Marginal Era (remember the theme song to Radio With Pictures, ‘This Heaven’?) and the big one we signed was The Mockers. They sold a shitload of records.

By then I’d started playing again. After producing the Danse Macabre album, the band split and from that Car Crash Set came together and asked me to produce and play guitar. At this point of time, Auckland was going into “club” mode – stupid haircuts, dumb fashions and serious drinking. My income was being subsidised by working in a record shop part-time but my real focus was on recording, learning how to approach media and the basic mechanics of running a small label. Looking back it was pretty much a case of scrambling around to make the rent but in the process learning a lot, making a name ... and having a good time.

Car Crash Set: Trevor Reekie, Sharon Tuapawa, Nigel Russell, Quays, Auckland, 1984

Car Crash Set eventually stepped up to the plate after starting as a recording band only. We began doing a moderate amount of gigging, chasing a sound that was somewhere between New Order and Alan Vega. We thought it was pretty revolutionary stuff and in some ways it was. Let's face it, the instrumentation we used back then was the prototype for the electronic instruments of today, except this was pre-MIDI. It was scary stuff, trying to get keyboards and drum machines to synch up in a packed, smoky venue while opening up for visiting acts like OMD, Hunters and Collectors, New Order and Shriekback.

And of course you wouldn’t get much stick for it, either from the Flying Nun anti-fashion fashion brigade. Not that we gave a fuck, I saw Nun for exactly what it was, pop music, image and tons of goodwill wrapped up in radical chic.

The combination of all this introduced me to the next opportunity. A film company called Mirage Films asked me to initially supervise music for some of their big productions – Came A Hot Friday, Bridge To Nowhere, Queen City Rocker, The Leading Edge – and in the process, begin a label, organise distribution, and create an identity. Was I interested? Hello …

Our label philosophy was “the only real alternative is to listen to all kinds of music”.

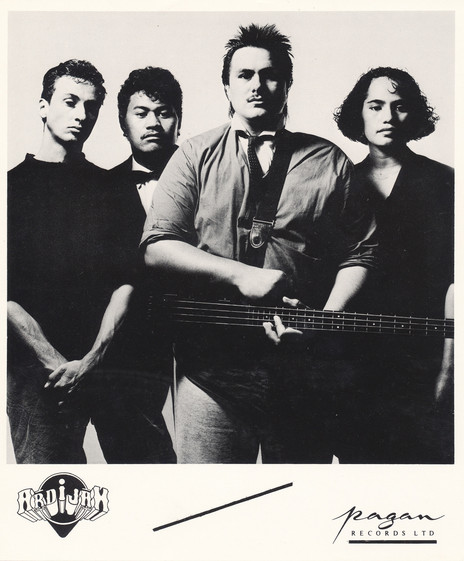

Running on empty, Pagan Records was born. It very easily could have fallen flat on its arse. It was never meant to be your usual indie type label. It was deliberately well out of comparison’s way of Flying Nun, they had their thing and I respected it. Our label philosophy was “the only real alternative is to listen to all kinds of music”, something the Nun people didn’t do. I remember driving to Wellington with Roger Shepherd once and I forced him to listen to The Warratahs (whom we’d just signed) all the way down there. Their first album was recorded for about $600 and went on to sell double platinum.

Pagan also signed Billy T. James for a live comedy album. Billy had been around every major record company in town, got turned down and came to us. I couldn’t believe it. The guy is and was a legend. His live comedy album went platinum on release.

We signed The Holidaymakers after CBS said no and had the biggest selling single of the year, outselling U2 – we also recorded an album with Shona Laing that ended up being released worldwide, going top five in Australia. Once again the local industry had pooh-poohed her because she had big hits when she was young and sang with Manfred Mann for a couple of years before returning home. We also had huge hits with Prince Tui Teka and Ardijah.

That same year the film company went into receivership, which meant the label was wiped out and it wouldn’t even have made history. I sensed the trouble looming six months before the creditors reeled in the film company and set up a trust account to safeguard artist royalties and creditors, controlled by my lawyer – very tickety-boo. And that saved my ass.

The artists were paid out and I took what was mine, which amounted to little more than a typewriter and some filing cabinets. The receivers appreciated they had a record label with admittedly a small, hot catalogue, but no one knew its value. Besides, every artist on the label exercised the receivership clause written into their contracts.

Ardijah's promotional portrait for their debut release on Pagan, Give Me Your Number, 1986. - Adrienne Martyn

I offered the receivers $1000 for the label. They laughed but within a week they accepted. I was now my own boss (just like the old boss), with my own business, my own PO box and not a lot else. Most of the artists came with me and before the end of that same year, we bounced back with a huge hit from Tex Pistol, AKA Ian Morris.

I have never ever done a budget or a spreadsheet. I’ve either said, “Cool let's make the record” or else said, “Piss off and chop meat somewhere.” I’ve never discovered an artist, just recognised them. Originally we focused on artists who were “roots” because they work a lot live and they’re cheap to record – I’ve made five albums with Paul Ubana Jones and the collective budget wouldn’t exceed $20,000. Paul sells a lot of records and is totally motivated by his own self-belief. The same goes for The Warratahs and Barry Saunders.

We signed a lot of pop stuff as well. Greg Johnson, Strawpeople, Hallelujah Picassos, Southside of Bombay, Shihad ... Making pop is expensive, very hands-on, and very frustrating. Hits are determined by the amount of radio you get and like everyone else we’ve had more than our fair share of hits that never were and should have been. We never had a hit with Strawpeople; eventually, the band got frustrated with us and ran off to Sony. We had a huge hit with Shihad but we couldn’t raise the budget to do their first album and we had to let them go. When they went the Picassos went with them, mumbling sheepishly about label identity and not wanting to be released on the same label that just sold 30,000 Bluespeak CDs. (Point taken – we started a second label called Antenna to separate the dented gents and the young folk.)

Greg Johnson was something else again. I personally rate Greg as this country’s finest songwriter. I love his words, his music, his sense of humour and his style. I was in his band for 10 years. That band was a hard-touring band and was always blessed with top-grade musicians. It also still holds the record at Bar Bodega for the heaviest drinking touring band to visit. We must have trashed that venue 20 times.

The Greg thing started courtesy of Mark Tierney from Strawpeople, who was working on Greg’s first recordings with This Boy Rob – I was sold on the opiate content of Greg’s music and since the Car Crash Set had just broken up we simply joined and called it The Greg Johnson Set.

There we were, with ‘Isabelle’, a huge hit single, and only a half recorded album.

Greg’s first album was made on and off at The Lab, using mainly Terry Moore from The Chills to engineer. It’s still a great record but it was the making of the second album that was a killer. If you could make a mistake making a record this was definitely our Apocalypse Now. We had a huge hit with ‘Isabelle’, a song that none of us had heard before we went in to record it (it was completed in six hours) and it was a monster surprise hit, with us being the most surprised. There we were, with a huge hit single and only a half recorded album, dumb and dumber. By the time the album was done the ‘Isabelle’ moment had passed.

Timing or destiny or fate or something also comes into pop. Darcy Clay died (rest in peace) and The Nixons had to change their name, tour America twice, had all their gear stolen and it wasn’t until they recorded their fourth studio album as Eye TV that they had their first hit single. Cruel. By that time the band had burnt out.

To tell you the truth I burnt myself out. One year before I moved into an office I was living in a kind of big boatshed made out of tin with a 35-foot stud. In winter it was freezing and when it rained you couldn’t talk on the phone. It had these huge wooden doors that I could barely open. I loved the place but it nearly blew me out. I had pleurisy three times and the label almost ground to a stop. My dad died the same year, a huge rite of passage for me.

Pagan's Sheryl Morris and Trevor Reekie with Paul Ubana Jones

That same month we recorded Bic Runga’s first stuff in a converted office in Wellington. It’s still brilliant music, some of those tracks appeared as B-sides to ‘Drive’. We never signed Bic, just went ahead and recorded a record. By the time she moved to Auckland, a bidding war started between Mushroom, PolyGram and Sony. Bic went to Sony, Shona Laing went to Sony, Strawpeople went to Sony, Ardijah went to Warners.

We all build our histories as tempus fugits – I’m shamelessly doing so here – people growing up in public get especially good at it when the spring of youth is receding and the tales and commentary are all that remain. Each one of us ends up in a different place. I blatantly admit to cultivating an image, a veteran with a thousand-yard stare.

The music industry is somewhere between crossing one’s palms with silver and cutting a deal with Lucifer. It rocks with ambiguity. On the other hand, it’s kind of a done deal. Music chooses those it taints, while many that choose music drop away. In Aotearoa, the odds aren’t brilliant. I got around it by never considering it as a job, more of a lifestyle. If you make a buck it’s a bonus. I still never know how to describe myself on a customs form, but I’m still living and breathing music. And I know now that it’s a career.