Tikao first sought out music through Sunday school. At six years old she would take herself to the library at Rowley Primary School every weekend because she enjoyed the singing. The first album she bought was from the Dance Exponents. Other music she was influenced by included Blondie, ABBA, and Donna Summer.

In school she took French and Japanese, but not te reo Māori. A strong interest in her culture didn’t come forward until university, when she started a Bachelor of Arts majoring in Māori Studies at Otago University.

“It was quite an awakening, learning about the history as well, the history of colonisation. Learning more about my own tīpuna ... It sparked a curiosity in what they went through, which I still feel like I’m learning about.”

It was while there that she did a paper on Māori art and artists. She learnt about some of the great Māori songwriters, including Tuini Ngāwai and Ngoi Pēwhairangi. There was a practical element to the course – she wrote poems and waiata. Tikao still sings two of those, ‘E Hoa’ and ‘I Kā Rā o Mua’.

Pounamu

After university, Tikao moved back to Ōtautahi and found herself part of a group organising the University of Canterbury Women’s Festival in 1992. She met some women singers and songwriters around this time, and they formed a group to perform in a lunchtime concert during the Women’s Festival. “We didn’t even have a name. We all wore purple and sang these feminist songs ... ”

The purple-wearing ensemble included Cathy Sweet, Jacquie Hanham, Margreet Stronks, and Ariana Tikao – then known as Liane.

At University, Ariana Tikao, Leigh Taiwhati, and Jacquie Hanham formed Pounamu.

In 1993, Tikao met Leigh Taiwhati who had posted a note on the board in the women’s room at the University of Canterbury looking for women songwriters to form a band. Tikao, along with Leigh and Jacquie Hanham (now Jacquie Walters) of the original purple-wearing ensemble, would go on to form Pounamu. Their first gig was as the opening act for a women’s dance.

“We didn’t have a name, even before we went up to play,” says Tikao. “We bandied around different ideas and Pounamu was the one that Leigh and I were thinking of. That was kind of my training group in music, I wasn’t really playing guitar, so I was doing mostly percussion and vocals and writing songs. I didn’t play taonga pūoro back then.

“That first gig that we did at the women’s dance didn’t really go down very well, I think they just wanted to get pissed and listen to music they could boogie to.”

Pounamu put together an album, Koha, which was released on tape. It is probably difficult to find the original in circulation anymore, but the original reels are in the Alexander Turnbull Library collection today. They paid for the album by taking on work recording jingles at a studio near Lyttelton. Taiwhati left after a year, but Tikao and Hanham continued and received funding from Creative New Zealand to make an EP. It was called Uha and featured a number of guest musicians including James Wilkinson, Richard Price, and Kelly Kahukiwa. While funded, the EP was still very much a DIY project.

Tikao talks about those early gigs where they would sell copies of the EP: “We were handwriting the labels onto hand-torn pieces of harakeke paper as people were arriving for the release concert at the Harbour Light Theatre.”

As a musical project Pounamu developed a reputation as being quite political, part of a groundswell of movements which were happening in the mid to late 90s. There was a lot of live performing at the Christchurch Arts Centre market, at university orientation and student marches. They performed at a the Composing Women’s Festival in Wellington in 1995, as well as the Fringe Festival. A lot of the music Tikao was writing revolved around identity, politics, and mana wāhine.

Pounamu was selected to tour Europe as part of an anti-nuclear testing campaign.

Pounamu was selected to tour Europe as part of an anti-nuclear testing tour sponsored by The Body Shop. Jacquie and Ariana were the representatives from Aotearoa, in a delegation that included young people from across the Pacific. They went to Strasbourg, making a presentation to the European Parliament, and lots of media events. They performed at the Fête de l'Humanité just outside of Paris with some of the others from the delegation dancing to their music.

Tikao tells a story about performing one of her songs to a man from The Body Shop, in a Paris café. Despite the song being in te reo, she remembers an elderly woman at a nearby table crying at the emotion of the melody, and how she somehow understood its meaning was to do with environmental issues.

She shares her thoughts about the differences in the contemporary Māori music landscape in those days. “Things were quite different back then. There were the local stations like Tahu FM, we could just rock up and quite often they would play the music. A lot of the Māori stations seem to be less community-orientated these days.”

Pounamu was chosen by Tahu FM to represent the South Island at the Gig on the Roof in 1994, a concert recorded on the roof of TVNZ in Auckland. They stayed at Hoani Waititi Marae (Oratia) in the lead-up to the show. There were Māori bands from across the country, mostly singing either entirely in te reo or bilingually. An exciting moment for Pounamu.

In 1996 Tikao moved to Palmerston North to pursue a post-graduate degree in Museum Studies. Pounamu recorded one more album together in Wellington, Mihi. They launched it at the Folk Club in Ōtautahi, and then Jacquie went to live in the UK the next day. Pounamu didn’t continue much after that.

Solo projects

Afterwards, Tikao followed a different path for a few years. She met her husband, moved to Sydney and to Tāmaki Makaurau, and then she had kids and moved back to Te Waipounamu.

It was the journey into motherhood that prompted Tikao to begin writing again. She went to a poetry reading by Hone Tūwhare. She asked him if he needed isolation to write, and Tūwhare replied with “write what you know”. She started writing poems and songs about her experiences as a mother.

the journey into motherhood prompted Tikao to begin writing again.

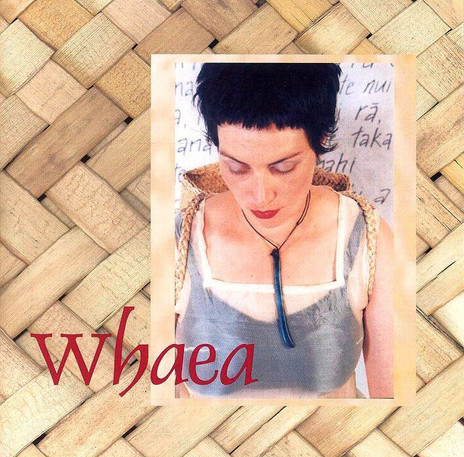

This resulted in her debut album as a solo artist – Whaea was released through maorimusic.com in 2002. The site was a platform for kaupapa Māori music, though it disappeared in unknown circumstances along with much of its stock. Nevertheless, it was this platform that supported Tikao to reach wider audiences. Whaea was played on iwi radio stations around the country and on Māori Television, and was represented internationally at the World Music expo, Womex.

The album moved away from being an entirely folk project and allowed her to introduce a more electronic sound. Playing this music live was a challenge for Tikao, and required a band. Richard Nunns had played on the album and was already known in the festival circuit. He started to play live with Tikao, and helped raise her profile to get Arts Festival bookings, etc. She was touring often, all while still raising two young children, working in the GLAM (cultural heritage) sector, and freelance writing.

Eventually, Tikao started work on her second album, Tuia. In 2003 she had met electronic producer Leyton (of Epsilon Blue and Rotor + fame) through a mutual friend in Ōtepoti. Their song ‘Kōrakorako’ featured on compilation The Green Room 002: Wahine, released by Loop in 2003, a label that Leyton was involved with at the time. It was through that single that Tikao secured funding for Tuia.

Released in 2008, Tuia was recorded between Ōtepoti and Ōtautahi and was primarily electronic. It also featured taonga pūoro, played by Richard Nunns. Some of the album was recorded in Tikao’s bathroom and hallway. “I don’t really have a lot of formal training in terms of vocals or a European music tradition,“ says Tikao, “so a lot of it is quite instinctive.”

Tikao worked with Louise Pōtiki Bryant to create a video for the title track. Tuia won Best Video at ImagineNATIVE Film + Media Festival in Toronto in 2009.

Following the release of Tuia, Tikao undertook a brief residency with the New Zealand Studies Research Centre at the University of London.

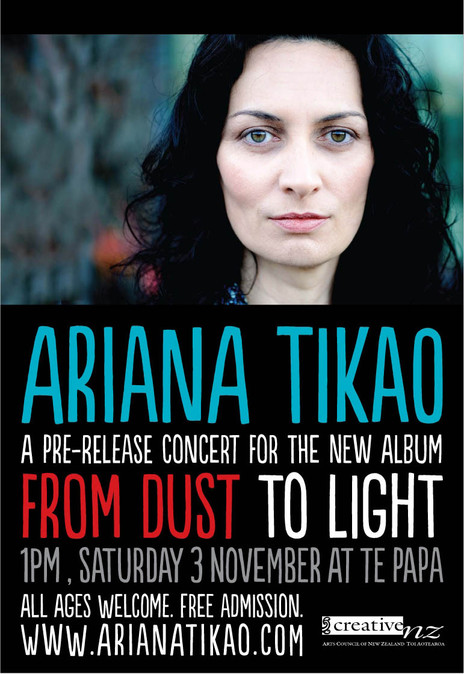

Her most recent solo album From Dust to Light was released in 2012.

Taonga Pūoro

Today, Ariana Tikao is one of many people associated with the Taonga Pūoro movement. The revival of taonga pūoro is a large and rich history, and in the 20th century the first wave of the revival was championed by the likes of Hirini Melbourne, Hinewirangi Kohu-Morgan, Brian Flintoff and Richard Nunns. It is appropriate to say that Tikao is one of several prominent figures from a second wave of that revival, mentored by whānau and by the likes of Nunns and Flintoff.

now, Tikao is one of many people associated with the Taonga Pūoro movement.

Tikao first met Richard Nunns and Hirini Melbourne at a taonga pūoro workshop at a Kāi Tahu Arts Festival in 2000. Nunns had heard of Pounamu, and that introduction was what eventually led to his involvement on Tikao’s solo projects.

About that first introduction to taonga pūoro Tikao says: “I really loved the sound of them but at the time I felt that they were too hard ... There was a perception that you had to be an expert to play.”

In the early 2000s, Tikao visited Flintoff at his studio near Nelson. He showed Tikao how to get a sound from the taonga, and she left with her first whānau of instruments: a big pūtōrino, a pūtātara, a kōauau, a pōrutu, and a porotiti.

Tikao was already familiar with the instruments in a museum context, through her post-graduate research. She had worked on creating new housing for taonga housed at the Whanganui Museum.

Tikao emphasises that taonga pūoro didn’t really feel accessible to her in the late 90s and early 2000s. Part of this was not having any wāhine role models to model her own relationship to the taonga on. But Flintoff in particular was very influential for her, supporting Tikao and her wider whānau to reclaim a relationship with taonga pūoro.

It wasn’t until much later, in 2016, that Tikao met Aroha Yates-Smith, an original member of Haumanu, and then in 2020 that Tikao and other wāhine players were able to connect with Hinewirangi Kohu-Morgan, another of the prominent wāhine figures in the revitalisation of taonga pūoro. Tikao was aware of Kohu-Morgan’s poetry at a young age.

There are several other figures who might be included in that second wave of the taonga pūoro revival, including Jerome Kavanagh and Alistair Fraser.

Today, the network of taonga pūoro players is vast, inherited by third and fourth and now perhaps even a fifth generations of players.

“When I first came in, people were used to seeing people like Richard Nunns there leading the kaupapa, who did great work at building the awareness of taonga pūoro. I feel like we’re starting to, not take it away from that space, but really broaden out their original kaupapa, and build upon what they did, when they went around all of those communities, gathering up stories of taonga pūoro.”

Despite many opportunities to work with taonga pūoro on a high-profile public level, for Tikao, the most exciting work is that which can be done on a community level, with hapū, iwi and whānau.

Collaborations

In recent years, it is the work of collaboration that has been the focus of most of Tikao’s projects. “I find it quite good, working more collaboratively and not being the main person because it can be quite exhausting carrying a kaupapa by yourself.”

Tikao often works collaboratively: “it can be quite exhausting carrying a kaupapa by yourself.”

One of those strands of collaboration includes work playing taonga pūoro with orchestras. Tikao’s first foray into this world was performing karakia and karanga with the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra’s In Paradiso in 2015; this work was supported by Richard Nunns. In that same year she co-composed ‘Ko te tātai whetū’ with Phil Brownlee for the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra and performed in that show as a soloist.

‘Ko te tātai whetū’ was the first taonga pūoro concerto, based on a mōteatea from Tikao’s great-grandfather Teone Taare Tikao. Because Tikao is not classically trained, that process involved working closely with the conductor for cues.

Tikao had worked with Louise Pōtiki Bryant on the video for Tuia, as well as videos for a show called Ōhāki in 2010. Later on, Pōtiki Bryant got in touch about the idea of working on a kaupapa based on a story from Tikao Talks – the collection of interviews with Tikao’s great-grandfather. The story was about atua wāhine of the winds. Tikao loved the idea, and Pōtiki Bryant eventually created the role of Hinearoaropari – atua of echoes – so Tikao could also be in the show.

The show Onepū was toured by Atamira Dance Company in 2019. Pōtiki Bryant and Tikao also worked on Te Taki o te Ua – a video installation with Paddy Free in 2022.

Two prominent collaborators for Tikao are Ruby Solly and Alistair Fraser. Tikao and Fraser met through Nunns at a Pao! Pao! Pao! show at Wellington Town Hall in 2008. Fraser supported Tikao with a taonga pūoro performance at that show. Fraser also performed some taonga pūoro on From Dust to Light (produced by Ben Lemi) and has since joined Tikao for many performances and shows. Together they released their collaborative album, Nau mai e kā hua, in 2020.

Tikao met Ruby Solly through the latter’s project towards a master’s degree in musical therapy. Solly interviewed Tikao for that work, and that led to lots of collaborations. They worked on each other’s performances for the Suffrage Songs Recomposed concert in 2018.

IN 2021 ALISTAIR FRASER, ARIANA TIKAO, AND RUBY SOLLY FORMED THE LABEL ORO RECORDS.

In 2021 Fraser, Tikao, and Solly formed the label Oro Records as a platform for their own music and that of like-minded musicians, especially those with a taonga pūoro focus. Through the label they also launched their collaborative project Tararua with Phil Boniface (double bass and taonga pūoro) and released their first album, Bird Like Men.

Tikao has also collaborated on work with Maianginui – a quartet of wāhine made up of Tikao, Ruby Solly, Te Kahureremoa Taumata, and Khali-Meari Materoa. The quartet was scheduled to perform with the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra in 2021, a performance finally completed in 2023 because of Covid-19.

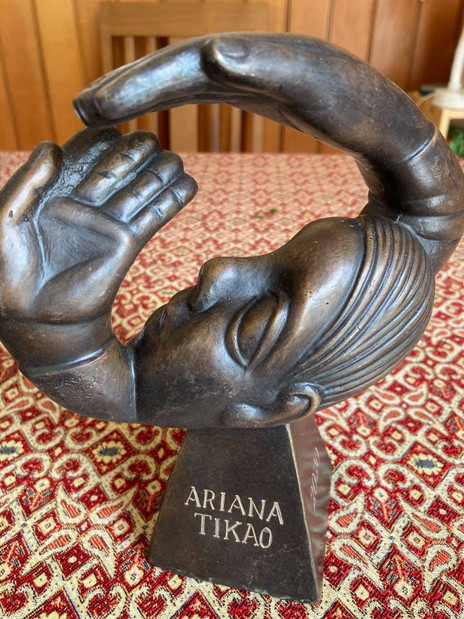

In 2020, Tikao was named an Arts Foundation Laureate. Her vision, drive, and passion for taonga pūoro and te ao Māori are relentless. There are countless other threads of her work that are worthy of note.

In recent years she has been focusing on rebuilding a body of knowledge about taonga pūoro and birthing practices. This work was supported by study of rongoā and a desire to see taonga pūoro returned to the healing realm. She has supported sound meditation work, as well as Māori antenatal classes. She supports a group for Māori mothers with Sam Palmer where whānau are taught how to make and play taonga pūoro. She is working with her cousin Kelly Tikao to introduce oriori – lullabies – back into the daily fabric of the young family back home in the Kāi Tahu rohe.

In 2022, Auckland University Press published Tikao’s first book Mokorua, with photographer Matt Calman and her partner Ross Calman. The book follows her own journey towards receiving her moko kauae.