Rob Hemi-Te Miha was an original member of the Māori Hi-Five, playing rhythm guitar, bass, and singing. Before he died in November 2007 he wrote a memoir for the iwi magazine Wairarapa Moana Mailer.

1. “Keep the beat and make it loud!”

At about age eight my palm was read, along with everyone else’s at the farm Waimarie in South Wairarapa. “This boy will play music in a very strange way,” was the verdict.

The matakite was a Mrs Jackson, from Tuai, mother-in-law to our uncle George Ahipene. Looking back over the many years of travel and work, her words accurately presaged events.

To avoid any misunderstandings, there are four or five people called Robert Te Miha around the country and several Robert Hemi – my parents were Hekenui and Hughina Hemi.

It was not until leaving college that music became a part of my life. An introduction to the guitar by a shearer started me off, on songs that were rather risqué. Travel was in my blood and in Tokoroa my friends, the Panapa boys, coaxed me into playing for Waikata kapa haka at Ruatoki in 1957. Canon Wi Huata was the kaiwhakahaere and his words to me were “keep the beat and make it loud!” I had come across several guitar players. The one who impressed me most was Barlow Karaitiana. He remained in my memory for years as one who played great rhythm, great chords and apparently didn’t drink either. A nice role model.

At Ruatoki, fate stepped up in the form of Ihaka Metekingi, of Pūtiki. He talked of forming a band and invited me to sit in with them that night, which I did. He re-appeared several months later at Tūrangawaewae, still talking about a band.

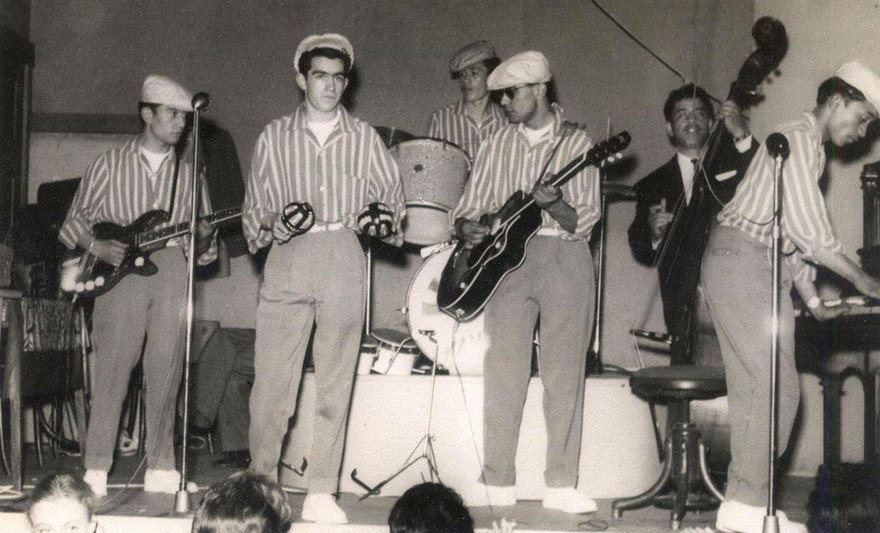

The Hi-Five Mambo in Whanganui, October 1958: Ike Metekingi, Costa Christie, Jimmy Rivers, Rob Hemi, "Fro The Pro" (a guest), and Sol Pohatu. - Costa Christie collection

Later that year I went to Wellington, and shortly after he appeared again. I was doomed. We formed a band, The Hi-Five Mambo (later to become The Māori Hi-Five showband) and took on Solomon Pōhatu and others. We got a stand in the Cubana nightclub in upper Cuba Street. Ihaka mentioned recently that he deliberately chose the band members not for their ability but for their “feel”.

During our time at the Cubana a lot of musicians came to look us over. Rana Waitai mentioned that they would come down from Rātana Pa now and then. Tommy Adderley would come and sing with us every time he was in town. Tony Eagleton from off the Dominion Monarch would sit in with us when he was in port. One night, Rupert Branker, musical director for The Platters, came up and sat in with us. And there were always lots of locals who could sing, ready to get up and join in. Later, we moved to the Trades Hall in Vivian Street. Here we ran talent quests every Sunday night. Mere Nimmo sang ‘Blue Moon’ which I liked and one night Isobel Whatarau came on to sing ‘Solitude’. In Wellington, we lived at 184 Willis Street along with Ruru Karaitiana and often had chats with him.

We did a few trips to Whanganui to do shows, one or two with Johnny Devlin. One day these young girls turned up, saying “we’re your cousins!” They were George Ahipene’s daughters (“Georgie Pop”). Old friends turn up even today, unexpectedly and in unexpected places.

Being a rhythm guitarist might have seemed an easy option in a band. It was hard work for a left-hander with two left feet. There were better guitar players in Wellington and my only advantage was playing with others who were far more talented and motivated me immensely. What made a huge difference to me was having Kawana Pohe join the band. He was an extremely competent musician and brought into the repertoire lots of great tunes. His forte was the sax and in my opinion he could hold his own anywhere in New Zealand at that time. Kawana was partially blind and our decision to go overseas was based on the need for him to have eye operations in London, which were carried out.

Looking back, part of the early training on guitar occurred at parties. Everyone sang in those days and having to follow singers was good ear training. In Wellington lessons were taken from Len Doran and, later, Dave Tatana. In London lessons were taken at the Ivor Mairants School of Music for a few months. Most of my style developed through adopting bits and pieces from the work of others. Circumstances dictated the way I would play, as a rhythm player.

Back to the polka. We did shows in Rotorua before leaving New Zealand, during Christmas 1959. Our last show was in Auckland at Carlaw Park. Shortly after, in January 1960, we left for Australia where we were welcomed by our old friend Johnny Devlin.

Music has been a good standby over the years. Here on the coast, schools provided employment for many years teaching young students to play the guitar. In recent years close contact has been maintained with my old band mate Solomon Pohatu of Muriwai. We play gigs now and then with two young chaps who like the way we play. It’s nice to be wanted!

2. The Māori Hi-Five Showband in Australia

In December 1959 the Māori Hi-Five showband went to Auckland, where we put on a farewell performance at Carlaw Park. (Among the supporting acts was the Howard Morrison Quartet – a famed exponent of the farewell performance in years to come.)

Sydney airport, 1960: how the Māori Hi-Five got their piupiu through Customs. From left: Paddy Te Tai, Tuki Witika, Rob Hemi, Wes Epae, Kawana Pohe, Solomon Pohatu.

We flew to Sydney, Australia, on 19 January 1960. We had no support body or sponsor so it was a “do-it-yourself” exercise. Here, I might add that virtually all the Māori showbands and entertainers who left New Zealand, from the Brown Bombers onwards, did so under their own steam with no assistance from anyone. This must be recorded, in view of the fact that much is made of musicians and entertainers now who sign recording contracts, TV contracts, etc, before venturing beyond these shores. There were sometimes no work contracts for a lot of the groups in those days. We went confident in our ability to get work and with no thought of failure or turning back!

The band personnel was: Kawana Pohe (Whanganui) sax, clarinet, piano, arranging; Waihuka Te Tai (Rāwhiti) lead guitar, bass, vocals; Rob Hemi (Wairarapa) rhythm guitar, bass, vocals; Solomon Pohatu (Muriwai) vocalist, bass, piano, sax, guitar; Wes Epae (Manaia) vocals, bass; Harata Tawhai (Auckland) vocals; Tuki Witika (Kerepehi) drums.

Our arrival in Australia can be viewed in the accompanying photo. We performed a haka on the tarmac and walked through Customs in our piupiu, a dodge designed to circumvent the difficulty of declaring a “grass skirt” – it worked.

The air hostess on the plane, Gay Allan of Dargaville, handled our luggage and clothes. Our old friend Johnny Devlin was there to meet us, along with Cole Joye, a famous Australian pop singer of the time. Sydney was stinking hot and we soon settled into the routine of drinking lots of liquid (any colour!).

Rob Hemi-Te Miha and Paul McCartney, Hong Kong, 1964. Photo-bombing them is Wes Epae.

Australia was a revelation. They appreciated, catered for and rewarded talent. Their venues made New Zealand equivalents look like garages. Here, it is fair to state that Australia provided, for Māori showbands, a proving ground from which to launch their shows into the top entertainment centres of the world and to “hack it” with the best. Some of the best included Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie (“just call me Bill”), the Beatles, Mel Torme, Harry James, Eartha Kitt, Johnnie Ray, and Billy Eckstine.

One of our first tours we were given on reaching Sydney was around the red-light district of Woolloomooloo. I have never forgotten it, the whole scene looked shifty and sordid. At another time, we called into a hotel down near the Cockatoo Docks at the bottom of McLeay Street in the early hours of the morning. While we were drinking, a guy came up and asked if we wanted a ticket in the raffle. We asked how much and he said, “A quid!” Then we asked what the first prize was. He looked over the bar at the barmaid and said, “Her!” We took to our heels.

Our first job was at Andre’s nightclub in Castlereagh Street: dinner, drinks, dancing-girl revue, with compere Joe Martin. TV work followed on various shows such as The Brian Henderson Show (he was a New Zealander), the Johnny O’Keefe show and the Coca-Cola show. Some funny things would happen at these TV shows. Once a camera came close by me; it had a card mounted on the lens barrel which read, “When in doubt, PANIC”. The mainly young audiences were exhorted by a guy running around between the cameras waving large placards entitled “SHOUT, SCREAM, LOUD APPLAUSE, LAUGH”, etc.

Then there was the occasion when the house band drummer fell back off his rostrum seconds before his drum solo; instead of a solo there was dead silence and a yell for help! On some shows we worked alongside three skinny boys who called themselves the Bee Gees. We did a show at the Sydney Town Hall for the then Mayor Jenkins. Nephi Shortland was present – a member of the Allen Brothers group and later in one of the Māori showbands. Another whom we ran into frequently was one of the greatest Māori entertainers, Kahu Pineaha. Also performing at the Latin Quarter nightclub was one of the world’s top jazz guitarists, Mark Kahi. On weekends, we would sometimes link up with another New Zealander, Derrin Hinch.

Sydney was followed by a long residency at the Skyline Lounge of Chevron Hotel in Surfers Paradise. Surfers was then a small town where high-rise was three storeys, max. As far as I know, we were the first Māori to live in Surfers. Here, we struck racial prejudice when attempting to join the Queensland Musicians’ Union. The matter was sorted out and we became members, finding out that the constitution was started to keep Aborigines out.

Māori Hi-Five, 1963. From left: Mary Nimmo, Kawana Pohe, Paddy Te Tai, Peter Wolland, Robert Hemi-Te Miha, Solly Pohatu and (front) Wes Epae.

(I digress here to relate an incident that shows how much impact the showbands achieved in Australia. In 2005 younger brother Spencer passed away in Manly, and upon our arrival at his home, I saw a picture of him with a message on the tree on the street outside. A car pulled up and a woman got out. As she neared me, she looked at me then exclaimed, “You’re Robbie!” I asked her how she knew me, to which she replied, “You were in the Hi-Five! I used to go and watch your band in Surfers Paradise!”)

As a group, we held karakia regularly, and on Sundays it was followed by a trip to the beer garden where, if you had travelled more than 50 miles, you could register your name, address, etc, and get a drink. Everyone knew each other in Surfers, so there were many “ghost addresses” each Sunday. The Surfers Paradise beer garden boasted a bandstand, next to which was the Ladies. Now and then the bandleader would stop the music and wait for the hapless victim to emerge. He would then ask her if she could hear the band, to which the inevitable reply was “No”. His retort was, “Well, we could hear you”.

This heartless bit of “fun” took an unexpected turn one afternoon when an outraged husband leapt on to the stand and felled the leader with a well-placed blow to the head!

Regarding beer gardens, they were relatively laidback venues; people walked in off the beach in togs. One day a guy walked through the beer garden, beer in hand, wearing only a grin, to loud applause.

All fun aside, Australia for us was a time of hard work preparing for the future. TV, beer gardens, nightclubs, extra shows, constant practice and rehearsal prepared us for what was to follow in the UK, the Continent, and Scandinavia. This association of the Māori showbands with Australia is at present being recognised in a planned documentary spearheaded by Nephi Shortland entitled Kia Ora, Mate! Around 1964 there were about 15 Māori groups, along with whānau in Sydney. The city was full of Māori entertainers. Why so many? An answer might be found in this quote by Leslie Lipson, a US academic – “It is acknowledged by all judicious observers that New Zealand is notoriously ungenerous to talent!” The evidence is clear in what is referred to here as the “brain drain” – in all professions.

At some stage in the saga, the Māori Hi-Quins arrived in Surfers, resulting in “a Māori on every corner” and some memorable times. We often put a hāngī down, usually at their place Brier Rose, as our place had no backyard.

It was in Australia that our show format was created, tested and perfected over the months and proved watertight over the following years.

Note that we weren’t the first Māori entertainers to travel to Australia. We were preceded by The New Zealand Quartet (aka The Brown Bombers), Mark Kahi, Kahu Pineaha, Tui Teka, Lenny Hutchinson and Barry Erickson, among others. Our contribution was to create a show format that others followed in some way or other, as well as the band names: the Māori Premiers, The Māori Volcanics, for example.

Once we left Australia, we rarely came into contact with the later groups. We’re still catching up with them. I recently contacted Kelly Haeata (the Māori Hi-Liners), whom I last saw in 1957 in Mangakino.

--

Rob Hemi passed away in November 2007.

This piece first appeared in Wairarapa Moana Mailer magazine in two parts: issue 4 (December 2006) and issue 8 (December 2007), and is republished with permission. Thanks to Henare Manaena of the Wairarapa Moana Incorporation.