Incubator control room, mid-1990s.

Incubator Studios was not a typical professional recording studio. Apart from anything else, it was situated in a six-bedroom flat. Yet it became a key part of Auckland’s inner-city cultures and turned out a string of iconic recordings – including two Taite Prize Classic Record honorees. So how exactly did it happen?

In March 1988, Mike Hodgson got a job as a field sound recordist for a TV news show. It meant moving from Christchurch to Auckland and he asked Angus McNaughton, his partner in the adventurous electronic collective Tinnitus, whether he wanted to make the move too. He did.

Incubator Recording logo.

They arrived in a car packed with gear and set about looking for somewhere to put it. They found Bristol House, a rundown building in Albert Street already full of artists and band rehearsal spaces – and the first Auckland office of Flying Nun Records.

But, like many old buildings in Auckland at the time, Bristol House was marked for demolition only a few months later. Hodgson went looking again and found a former clothing factory (and before that, a ballroom dancing studio) above the shops at 203 Upper Symonds Street.

Incubator Recording studio at dusk.

They moved in their gear, built a basic studio, and gave it a name. Their former Albert Street room had contained an old egg incubator (“goodness knows why,” says Hodgson). They removed the “incubator” plaque, stuck it up in the makeshift recording room they’d made and Incubator Studios was hatched.

The pair began recording other artists and performing live in the studio.

Ant Nevison, Janet Sergeant and Gordon Rutherford during construction of the upgraded Incubator.

“One highlight was a long live-to-air from Incubator in March 1989,” Hodgson recalls. “Rick Huntington from bFM had said if we could install a double twisted pair phone line into the studio, he had a box that could encode the stereo signal from Incubator and broadcast it in high fidelity. We got sponsorship from [clothing label] Virus and had this line installed for a year so any DJ could flick a switch and we could play a new mix straight from the studio on air.”

But the duo’s plans began to diverge. By 1990, McNaughton wanted to build a proper recording studio, says Hodgson, and “I was keen to just stay in my underground space, so I moved into another warehouse across the road and set up Pitch Black Studios,” which duly gave its name to the musical duo Hodgson formed with Paddy Free.

McNaughton found a couple of business partners, Gordon Rutherford and Anthony Nevison, both several years older than him but still in their twenties, to help make the professional studio dream a reality.

“I always give Gordon the most credit in terms of saying, let’s take it seriously and make it happen,” says McNaughton. “I wouldn’t have been capable of doing it so professionally. He was very motivated.”

Stinky Jim and Mike Hodgson trouble the decks at an Incubator party.

Rutherford, the former drummer in Nocturnal Projections, was now working for the audio hire company Oceania and Nevison had returned from working at Battery Studios in London (where Samantha Fox, among others, recorded) to a job at the production hire company Dreamhire.

“I made a lot of money then flew to New York and went to 48th St where all the music shops are and walked in with a list,” Nevison says. “I bought reverbs, a sampler, all the stuff, and shipped it back to New Zealand.”

Nevison joined the Headless Chickens and took a new job at Mascot Studios. Without telling management, he sneaked the band in during weekends and the single ‘Gaskrankinstation’ was recorded for no more than the cost of the tape. It was a big change from the Chickens’ first album, Stunt Clown, which saddled the band with significant debts – and they decided they liked working without the meter running.

In its first incarnation, the Symonds Street studio also housed the workspace where Louise Maich made paper mâché objects. The Christmas trees were brought over from Bristol House.

Construction of the new studio commenced. “We got bFM to advertise for mattresses – with no maps of Australia on them – to go on the walls,” Nevison recalls. “And then we got 400 sheets of gib delivered onto Symonds Street and me and Gordon and Angus and his architect friend Robin Walker hauled them up there. We built the whole thing with no council consent. It was so heavy it could’ve just fallen through the floor.”

McNaughton’s experience with Tinnitus influenced the way Incubator worked. It was not only a different kind of studio space but the recording process itself was different. Years before ProTools brought cut-and-paste editing to musicians’ desktops, Incubator offered new ways of recording.

“Sampling was one of the big things for me,” says McNaughton. “I really embraced it as a creative tool. I could chop up and rearrange material, allowing for flexible songwriting in the studio – something that’s taken for granted today. A lot of clients who didn’t have access to any of this in their home studios at the time really liked working at Incubator, writing and producing songs from scratch.

“We had an Atari ST computer that couldn’t really record audio but it had quite powerful 64-track midi sequencing. We were still using the good old 16-track reel-to-reel, but then synchronising the Atari to that and layering a whole lot of electronic music production live on top. So we were able to get the 16 tracks of audio and add on a whole lot of samples live in the mix – it meant you could put a lot of layers together.”

Building Incubator.

The first project in the new studio was NRA’s album Hold Onto Your Face. The next would eventually become Headless Chickens’ Body Blow, with Visible producing – and pretty much anyone who was handy engineering.

Headless Chickens - Body Blow (1991)

“We had at least five people who could operate the machinery, so you didn’t have to worry about all that stuff,” says Headless Chickens’ Chris Matthews.

“Right from the beginning of the band we always operated in a studio environment – it was me and Michael and Johnny writing and recording onto Michael’s four-track. So recording with these guys who built their own studio in their house was perfect for us. We didn’t really have time constraints – it was just, do it until it’s right.”

The lounge (and former dance school) at Incubator.

Incubator was a home, a six-bedroom flat, as well as a workplace. The three owners lived there and Nevison’s partner Helen O’Connor oversaw a makeover of the kitchen, with its iconic Atomic coffee-maker. Rutherford’s partner Janet Sergeant used it as a base of operations while she and Hilary Ord set up Verona café on K Road.

“It was a social scene, it was part of the K Road café scene. It was a creative hub,” says McNaughton.

And then there were the legendary parties.

“Gordon would get the PA, the DJ gear and the smoke machine from Oceania,” says Nevison. “We’d lock the door after about 10pm and there’d be 200 people there. We charged five bucks for a Heineken and a shot of tequila.”

Incubator party.

Incubator’s status as a kind of community centre gradually receded as Rutherford moved to London and Nevison to Muriwai and it became effectively McNaughton’s space.

“It was my whole world really, so I was just sitting there doing the bulk of the actual studio engineering.”

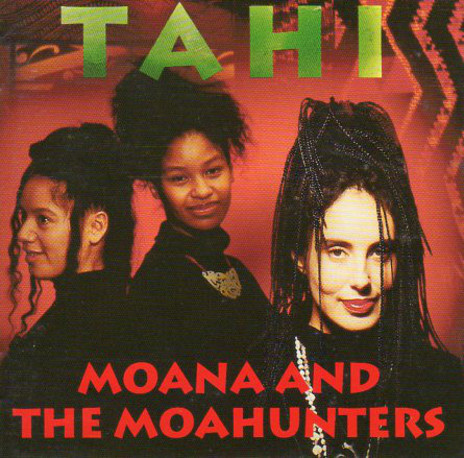

Murray Cammick directed much of the recording work for his Southside and Wildside labels to Incubator – including Moana and the Moahunters’ Tahi.

Moana and the Moahunters - Tahi (1993)

“The only studio I’d been in before was Mandrill, where Dalvanius would do his work, which was quite flash, and what’s now The Lab,” says Moana Maniapoto. “It was very funny, because Incubator wasn’t flash. I remember going upstairs and there was this tiny little cupboard that you went into, which was the vocal booth. And I liked that as a vocalist – because I found standing in the middle of Mandrill’s A studio quite daunting. This was a nice, intimate space.

“I loved Angus. He was like a big kid and we got on really well. He let me drag him around the country to sample things, haka slaps and all that. And he would sit there on his machine and start turning the knobs and he’d just almost be levitating, this big grin on his face. It was like a childish enthusiasm and he really liked exploring the traditional Māori elements were doing – and then he’d bring his beats to the party.”

Incubator.

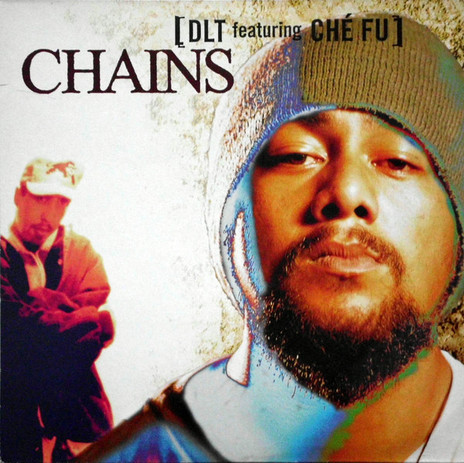

Later in the 90s, Incubator produced DJ DLT’s 1996 album The True School – and its iconic single, ‘Chains’. The single was a product of Incubator’s style of recording – and its attitude to extended hours.

“‘Chains’ went through quite a number of revisions,” says McNaughton. “It really started off as more of a downtempo Pacific reggae beat and originally Che wrote lyrics about his family having to move out of Ponsonby to South Auckland, that wave of gentrification that was happening at the time.

DLT featuring Che Fu - Chains (1996)

“We wound up going through about five different revisions and really all we kept was the chorus hook, because that was the catchy part of it. They rewrote the verses to be a much more global concept. And right at the very end we said, right, the reggae beat’s not working, so put in this much harder hip hop beat that we’d sampled off vinyl – and it all came together.

“I facilitated the time we spent doing that. I’m actually one of the writers on ‘Chains’ – back then I would be more likely to negotiate with artists to get a cut of their songwriting. That was my justification for proving hundreds of hours of studio time for very little cost. If I’m going to help develop the song and program it, I’m putting a lot of ideas in there. So I’m a 15% songwriter on ‘Chains’.”

Incubator control room.

3 The Hard Way’s ‘Hip Hop Holiday’ was also recorded at Incubator (it was a hit only after the removal of a whacking great sample from the 10cc’s ‘Dreadlock Holiday’, in response to a legal threat). MC OJ and Rhythm Slave and their subsequent project, Joint Force, also recorded there, as did Upper Hutt Posse.

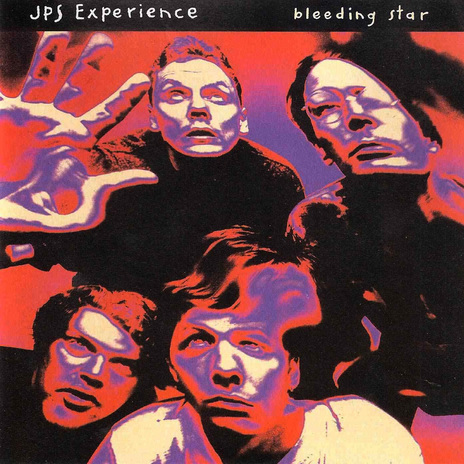

There were indie bands too, including HDU, Solid Gold Hell, Hallelujah Picassos and The Terminals. The final album from Jean-Paul Sartre Experience, Bleeding Star, was made at Incubator and most of Dimmer’s I Believe You Are a Star was mixed there. The soundtracks for Alison Maclean’s film Crush, Lisa Reihana’s Tuawera and Garth Maxwell’s When Love Comes Along and Michael and John Sheils’ 1994 Red Scream (New Zealand’s first CGI short film) were recorded at Incubator. There were TV commercial soundtracks and jingles, and sound for early CD-Roms produced by Terabyte Interactive.

Jean-Paul Sartre Experience's final album Bleeding Star, produced by Mark Tierney (1993)

But Incubator, which had so many connections to Auckland’s 1990s inner-city scene, would prove to be a 90s story itself. In 2000, a little over 10 years after it became a professional studio, Incubator closed down and McNaughton moved out, becoming an audio production teacher and one of the country’s most respected mastering engineers.

“It came to a natural conclusion where it was just time to do something else,” he says. “The lease ran out, the work dried up a bit and it was time to move on.”

Moving out, Incubator.

But the structure of the studio stayed. The three original partners had rather overdone their construction and soundproofing and McNaughton wasn’t about to try and remove it on his own.

Remarkably, it didn’t go to waste. Another budding producer, Andrew Buckton, found the space in a newspaper ad in 2001 and re-established it as Studio 203, which turned out recordings by successive generations of artists – Head Like A Hole, Tahuna Breaks, Clap Clap Riot and many others – until he, too, called it a day in 2014. But that’s a whole other story.