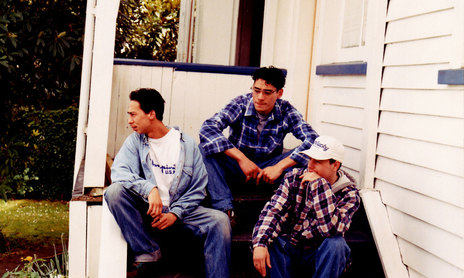

If Chris Ma’ia’i’s father had his way there might not have been a group called 3 The Hard Way. A doctor from Samoa, he wanted his son to attend Auckland Grammar, but the culture of the school didn’t suit the West Auckland boy and he insisted on being transferred to nearby Waitakere College. It was here that Ma’ia’i met Grant Kearney (Sample Gee) and, after school ended, he joined up with his group Total Effect. They soon became part of the newly evolving dance party scene that was happening in the central city in the late 80s.

A number of the dance hits at the time included rappers in the mix (think: C+C Music Factory and Beats International), so there was an open-minded attitude towards having hip-hop acts playing in the midst of dance music sets. Total Effect found themselves playing alongside other upcoming hip-hop acts like UCD, Syndicate Steppers, the Semi-MCs, Enemy Productions (early group of Dei Hamo), and the Power & the Glory.

At the heart of this scene were the Voodoo dance parties and talent quests put on by DJ Andy Vann (then a part of Voodoo Rhyme Syndicate, which included the two singers who would go on to be Sisters Underground). Ma’ia’i featured on one of the Total Effect tracks released on the AK 89 – In Love With These Rhymes compilation (put together by bFM station manager, Simon Laan, as a response to the Flying Nun compilation, In Love With These Times).

Through Grant Kearney, Ma’ia’i met Alan Jansson – a talented producer, who’d already had a string of hits in the 80s with his synth-pop group The Body Electric. Ma’ia’i and Jansson formed Chain Gang and had two hits of their own with ‘Break the Beat’ (which reached No.22 in 1990) and ‘Jump’ (which hit No.16 the following year), both driven by the deep, commanding rap style of Ma’ia’i.

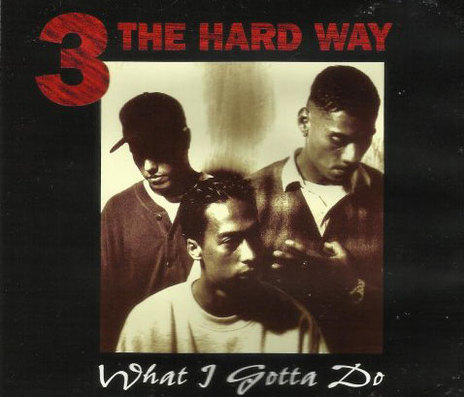

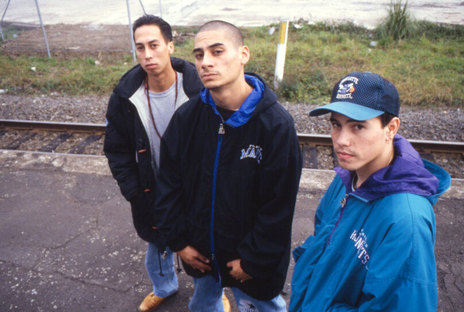

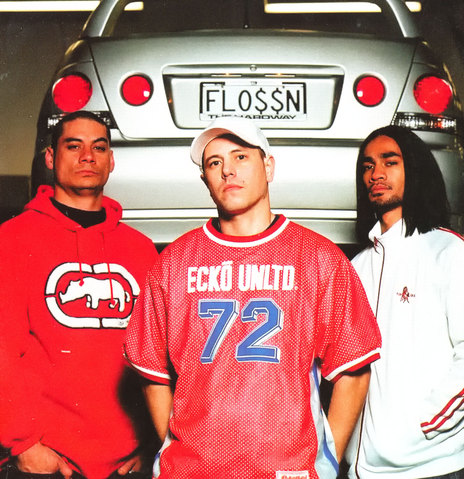

Meanwhile, Ma’ia’i had formed his own hip-hop crew with another former schoolmate – Lance “DJ Damage” Manuel. The pair joined with DJ John Petueli to form the BB3 (with Ma’ia’i taking the name “Voice C” or, later, “Mighty Boy C”) and they took on a more uptempo approach inspired by the Miami Bass sound that was popular at the time. Manuel also intended to start his own DJ crew with another turntablist, Mike “Mike Mixx” Paton so they could work on cutting and scratching over instrumentals. Ma’ia’i heard that they’d been working together and saw an opportunity to get further back into the world of hip-hop so asked if he could join them. Kearney gave them a slot at dance club DTMs (on K Rd) and, without a second thought, 3 The Hard Way was born.

The trio began gigging around town and, after one show, Ma’ia’i met influential local DJ/producer Mark Tierney (Strawpeople), who said they should approach a new independent label, Deepgrooves, that was interested in releasing local hip-hop. This led to a meeting with the label’s owner, Kane Massey, and an agreement to do a single-by-single deal.

The group began teaching themselves production – joining with Lucky Luciano Lopesi to form Hang Em High Productions. They recorded their first tracks at Incubator studio with Angus McNaughton, who’d made his name primarily as the recording engineer and live soundman for the Headless Chickens but who would soon gain respect in the local hip-hop scene (working with Joint Force, DLT, and Kidz in Space).

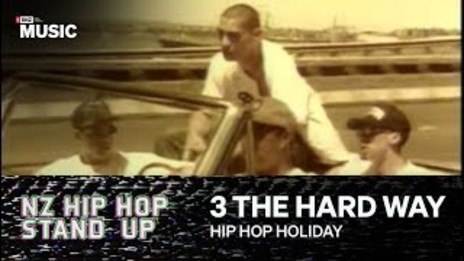

Hip-Hop Holiday hit No.1 in early 1994, reaching gold status, and a few months later it broke in Australia, reaching No.17 and staying on the Top 40 for 13 weeks.

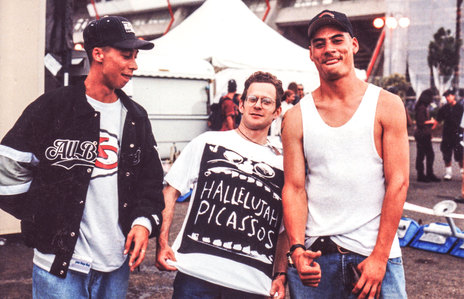

The members of 3 The Hard Way came up with the idea of doing a version of ‘Dreadlock Holiday’ by 10cc – an unusual choice of material for a hip-hop group, but Manuel and Paton had both worked as party DJs and knew the track had a great hook. All they had to do was switch out the word “reggae” in the chorus, so the refrain was “we don’t like hip-hop, we love it.” Yet the original reggae influence was kept by arranging for the singer, Bobbylon (Hallelujah Picassos), to do a verse of ragga-style toasting – it was meant to just be a short interlude, but after he’d done his first take, the group were so impressed that they gradually gave him more room on the track.

The original melody from the 10cc song was re-recorded and the tune was moved into a different key, so the people at Deepgrooves believed there wasn’t any necessity to contact the original composers of the song. After all, this was just going to be a run of 500 singles that would introduce 3 The Hard Way to the local market …

The song blew up. It was good timing for the track to arrive, since Ngāti Whātua had started a new station, Mai FM, in mid-1992 and it now provided a solid audience for hip-hop and R&B music (especially when combined with airplay on student radio). 'Hip Hop Holiday' hit No.1 in early 1994, reaching gold status, and a few months later it broke in Australia, reaching No.16 and staying on the Top 40 for 13 weeks. A 40-day tour was arranged across the Tasman and Urban Disturbance were taken as a support slot, along with Bobbylon.

By the end, 3 The Hard Way had sold over 50,000 copies singles throughout Australasia, but there was a problem. The original rights had never been cleared, even after 10cc’s lawyers had written to complain of the copyright breach. After six months with no response, they successfully petitioned to take all the royalties from the sale of the single and 3 The Hard Way were left with nothing.

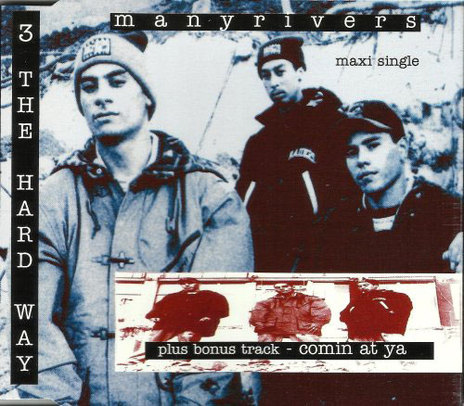

Meanwhile, the group had continued onward. Their next single, ‘Many Rivers’, was another attempt to draw from classic reggae – turning a Jimmy Cliff number into a hip-hop track. It reached No.10, buoyed by the sweet vocals of R&B singers Cherie Mathieson and Sulata (the latter also released an album through Deepgrooves).

Their album, Old Skool Prankstas (1994), was hurriedly recorded and released. Further tracks had since been recorded at Revolver studio with Malcolm Smith, usually with the help of Anthony Ioasa (Grace) who also added keyboard parts and helped with production. The result was a laidback form of g-funk, with a jazzy, backpacker edge to it and plenty of cut-up vinyl (especially on ‘DJ’s Nightmare', on which Manuel and Paton were joined by DJs Petueli and Ned Roy for a total scratch-fest). The album just managed to sneak into the Top 50 although it achieved platinum sales in 1995. A third single, ‘All Around’, hit No.22.

Yet, the relationship between 3 The Hard Way and their label was soured by the lost royalties from ‘Hip Hop Holiday’ and eventually the group decided to sit out their contract rather than be forced to continue working with them.

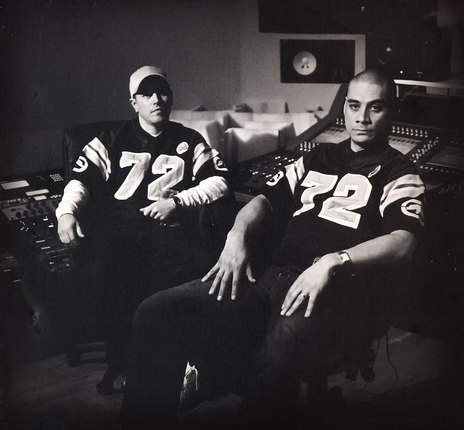

Four years passed before they turned their minds back to re-starting the group, by which time Manuel had quit (eventually moving to Australia). Their early success was now too far in the past to open doors for them and it wasn’t until a further four years had gone by before they were finally ready to start work on a new album. Ma’ia’i knew exactly who he wanted to work with this time around – his old Chain Gang writing partner, Alan Jansson.

‘It’s On’ reached No.1 and pushed the subsequent album, Eyes On The Prize, to No.14.

In the interim, Jansson had been a key force behind the track ‘How Bizarre’ by OMC, which had topped charts throughout the world. Through this connection, the group hooked up with Simon Grigg (who’d also been involved with the overseas success of OMC) and signed to his label Joy Records, with distribution through Sony. Jansson had been recording with OMC backing singer, Sina (Siapia), and brought her on board for the 3 The Hard Way album. However it was a track recorded with singer, Clem Karauti, that proved to be the hit – ‘It’s On’ reached No.1 and pushed the subsequent album, Eyes On The Prize (2003) to No.14. Both went gold.

A lot had changed in the intervening years. When the group had first started, there was a dismissive attitude to hip-hop within the wider culture and Radio Hauraki, The Rock (Hamilton) and 89FM (Auckland) radio stations even had ad campaigns that proclaimed that they played “no rap, no crap.” Now hip-hop culture had gone mainstream and 3 The Hard Way’s new problem was that they had fight for a share of the limelight against younger acts like Scribe and Nesian Mystik.

Even more problematic was the time pressures created by the fact that both Chris Ma’ia’i and Mike Mixx each had a couple of children. Their comeback had been successful but they didn’t have the energy to make it stick and eventually decided to go their separate ways. They’d helped break rap music to a New Zealand audience – not once but twice – and could now look back as godfathers of a thriving local hip-hop scene.