In the early 1990s grunge had landed, Britpop was taking off and Flying Nun’s leading bands were internationally airborne. Auckland’s live scene was enjoying a continued purple patch, while Dawn Raid and local hip hop were looming on the horizon. Meanwhile, University of Auckland student radio station 95bFM was squarely in the heart of what was happening, gaining momentum and starting its journey to becoming a music-led subculture phenomenon.

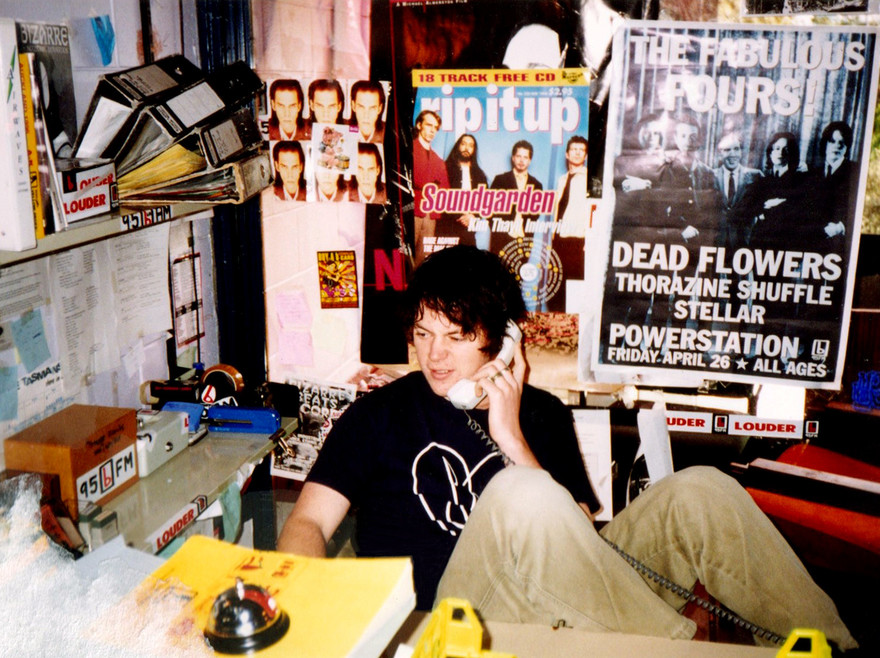

Nick Dwyer in the bFM studio. - Photo by Graeme Hill

At its peak, 95bFM’s 60,000 bCard holders and a much wider audience shared a common cultural heart. Several major, hand-picked advertising brands had direct access to, and credibility by association with, an audience they wouldn’t have otherwise had. Events were staged that people still talk about. Crucially, local artists and alternative music had an unrivalled platform offering a level of exposure that is hard to imagine in today’s multimedia world.

By this stage the station’s story had already been unfolding for two decades. As covered in Russell Brown’s bFM – the first ten years, Radio Hauraki wasn’t the only station to start on the ocean waves: “During capping week in 1969, a group of University of Auckland students got together and broadcast pre-recorded programmes from a borrowed boat on the Hauraki Gulf”.

During the early 1970s Radio Bosom, as it was then known, belted out music through big speakers around the university quad, raising the ire of some. Later, renamed Radio U, a small team of enthusiasts made sporadic pirate broadcasts from an on-campus hideaway and several flats across the city until diligent Post Office inspectors eventually caught up with them.

It seems remarkable now, but the Minister of Broadcasting got involved. There was “a question in the House” about an alleged call he made on air to the Radio U ringleader, suggesting it would be wise to stop broadcasting as there might be a possibility of the pirates getting a legal frequency in the future. How the minister came by the phone number was never revealed. (Read Russell Brown’s bFM – the pirates.)

The station eventually got a frequency, two in fact – 1404 AM and, from 1985, 91.8 FM, and broadcast as Campus Radio during term time on a series of Short Term Broadcasting Authorisation licenses. Debbi Gibbs managed the station in 1984, and successfully worked to get the station its first FM licence in early 1985. She was followed by Andrew Bishop (1985) then Jude Anaru (1986-1988). Anaru led the process of gaining a permanent licence, which was awarded in 1989, by which stage Simon Laan was manager; earlier in the 80s, Laan had lobbied Gibbs and Anaru to establish a subscriber card. At the start of 1990, the station became 95bFM; a year later, the next manager, Liz Tan, sat down with her then-flatmate, John Pain, to create the bFM logo with its small “b”. (In September 1990, Tan became the youngest station manager in the history of bFM, taking the controls when she was 21.)

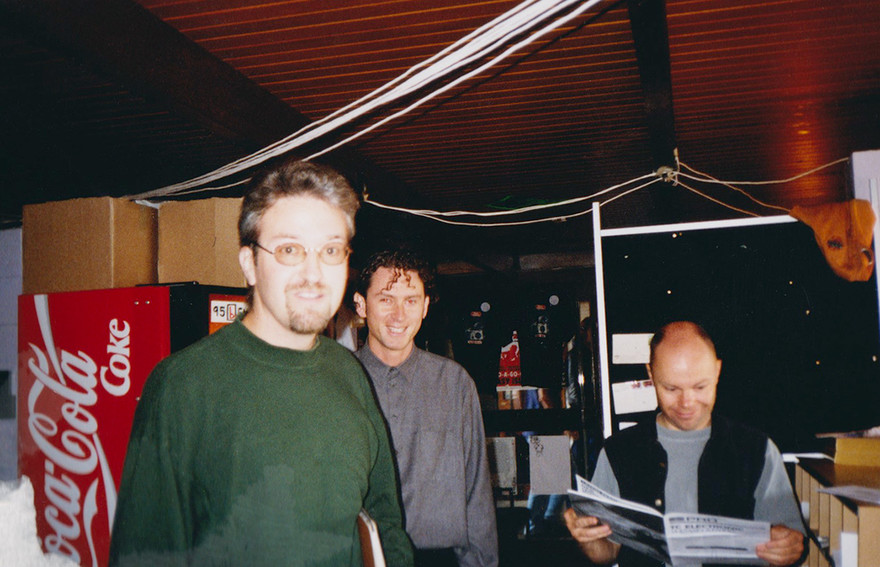

95bFM board member Mark Green, and station manager Adam Hyde with technical director Rick Huntington at right. Photo by Graeme Hill

Technical Director Rick Huntington was there when the intitial shift from AM to FM happened over Christmas 1984. He managed the transfer and is still running the technical side at the station in 2025. He also co-hosted In the Pink, bFM’s gay show that ran on Sundays from 1991 to 1996.

Huntington is considered a bit of a legend by everyone. Programme director and Breakfast host Graeme Hill explains, “Rick does, well, erm … everything, from the soldering iron to broadcasting masts, from studio design to builds, all with tiny budgets.”

Seemingly unflappable even on the later bFM Breakfast Bus broadcasts, Huntington is a master of the mysterious science of broadcast sound. “No one really understood how he did it,” says Hill, “but while Hauraki were a bit louder, they sounded shit compared to ‘b’. We always sounded much better.”

Ever cheerful, devoted to the cause and oblivious to any politics, Huntington has remained a constant as generations have come and gone. “He even helped the guys at George FM get their sound right when they started,” says Hill. “He just wants Auckland to have good music on air”.

“I’ve built and rebuilt the place a few times from the flooring up,” says Huntington, “... I keep it going I suppose, and I’ve done all the outside broadcasts.”

The Breakfast Bus broadcast became quite notorious. On one circuit of the city, Mikey Havoc at the helm, Garageland stopped morning traffic and rattled windows playing their new single ‘Nude Star’ on Takapuna’s Killarney Street.

From New Year 1986 and onwards bFM was a fully functioning student station, on air 18 hours a day and non-stop at weekends, supporting a wide range of genres and giving New Zealand music a much-needed outlet. It had grown a loyal, mostly student-based following when Graeme Hill was appointed as the first permanent, paid Breakfast host in 1989.

A new era

Graeme Hill stayed with the station until 1996, rotating between the Breakfast and programme director roles, at one stage doing both, “which almost killed me”. He avoided death by bringing Marcus Lush onboard to take over Breakfast. Hill later returned to Breakfast for a final year in 1996, by which time he’d also introduced a young Mikey Havoc to the Friday afternoon Drive show. During these years Drive had different hosts each day. As well as Mikey Havoc, Mark “Slave” Williams and Otis Frizzell (MC OJ & Rhythm Slave) hosted Wednesdays. (It’s a format the station returned to in the 2020s.)

“During the early and mid 90s a lot of what we know as bFM became solidified,” says Hill. “Permanent, paid breakfast hosts, The Wire, the logo, the bCard, specialist shows, the whole ethos … all things that are still the same in 2024. I credit Paul Casserly for instituting and institutionalising the bulk of these.”

Able Tasmans: Graeme Humphreys and Jane Dodd, bFM Summer Series, 1995 - Graeme Hill collection

Hill and Lush took things to a completely different level, introducing a new style of broadcasting in a land where the main options on offer were Americanised commercial radio, religious affiliated stations, talkback, or the then very straight-laced National Radio. Mainstream broadcasting was a void for music fans wanting anything outside Casey Kasem’s American Top 40, classic hits, easy listening, or Concert FM.

bFM's Gemma Gracewood at left, Grant Osborne second from right.

Others followed, many of whom have gone on to careers in mainstream media. Among them: Havoc, along with Jeremy Wells/Newsboy, Wallace Chapman, Charlotte Ryan, Noelle McCarthy, The Professor, Hugh Sundae, Jennifer Weathercentre, Jason “Rockpig”, Pheobe Fletcher, Gemma Gracewood, Damian Christie and Camilla Martin, and others.

Hugh Sundae. - Photo by Graeme Hill

Camilla Martin personified the “living the brand” youth culture aspect of the station. Like Hugh Sundae before her, she started hanging around bFM while a teenager still at school. And like Sundae she went on to be one of its enduring personalities and taste makers. The first woman to host Breakfast, she took it over in 2004 aged only 20, offered the job by station manager Aaron Carson. Her two years on Breakfast were a real success.

Wallace Chapman, known to many from RNZ’s The Panel, moved from Dunedin to join bFM as creative director. Working with Richard Larsen he took responsibility for the station’s already idiosyncratic ads for several years and hosted “a slightly crazy late night show every second Friday between 10 and 12pm.”

Station managers included Simon Laan (after Anaru), Harriet Crampton for two years from 1991, followed by Geoff Devereux in 1993-94, and Adam Hyde in 1994, who oversaw Flying Nun’s God Save the Clean covers/tribute album. Suzanne McNicol took over in November 1997, staying in the job through until the end of 2001.

bFM staffers Ben Hill, Jubt Avery, Johne Leach and Suzanne McNicol, at the bFM 25th anniversary gig, the Powerstation, c June 1999.

McNicol remains enthusiastic about bFM. Reflecting on the station manager role, she says, “It’s a pretty multifaceted juggling act, trying to run a viable business, liaising with auditors, preparing board reports, coordinating and mentoring up to 100 volunteers and managing the paid team, while trying to foster and not kill the all-important vibe of the place, and ensure it’s a good radio station.”

Nigel Horrocks hosting the Jazz Show, early 1990s

Outside of Breakfast and Drive, bFM’s morning, lunchtime and afternoon shows offered variety and an intelligent connection with what was happening in the world. There were the varied volunteer-run specialist shows that remain pivotal to the station’s relevance: Dirtbag Radio and Dubhead’s The Rhythm Selection. New Zealand music showcase Freak the Sheep. The True School Hip Hop Show. Friday night’s Gang of Four. And Sunday’s Jazz, Border Radio and Hard, Fast and Heavy shows. They still feature as appointment listening for many music fans.

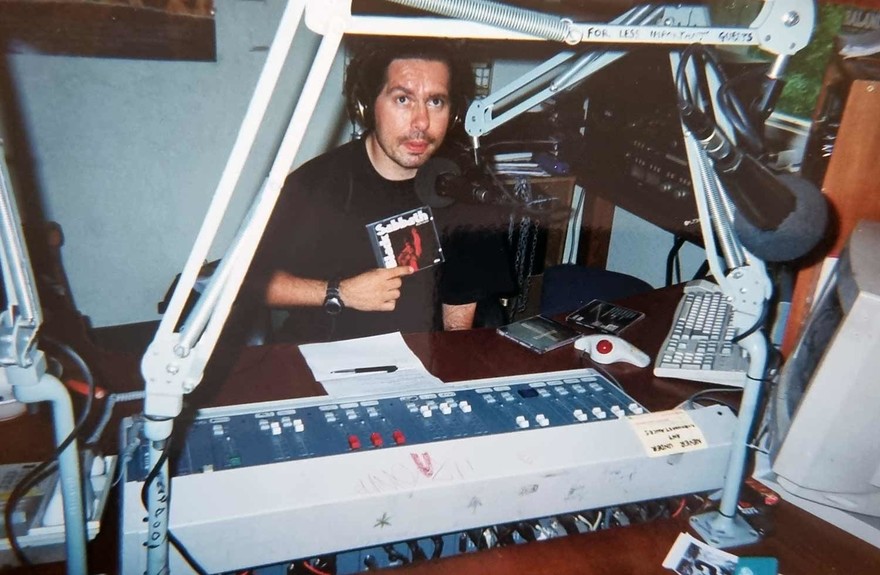

Hard, Fast and Heavy show host Sicoff (Simon Coffey) in the bFM studio - Simon Coffey Collection

Good grooves

One of the strengths of 95bFM in the 1990s was the conscious decision to build on the weeknight specialist shows. Stinky Jim’s Stinky Grooves arrived in 1990 and soon evolved into an institution, focusing on an eclectic mix of dub, reggae and the newer flavours of dub-focused club music, on a midweek evening for two hours, and joined Dubhead’s The Rhythm Selection.

Murray Cammick’s Land Of The Good Groove was already long established as the station’s soul and funk show on Tuesday evening when Simon Grigg took over the Beats Per Minute show from Simon Laan in 1989. Grigg focused on a mix of hip-hop and house music, initially on a Monday. In 1990, Graeme Hill consolidated all the dancefloor shows on Thursday evenings and added The Kaos Techno Show with Sam Hill and Sample Gee in 1991, which played a mix of rave and early bass music.

DJ Rob Salmon joined Grigg on the BPM show in 1991 and, when Salmon moved to NYC in 1995, he was replaced by Greg Churchill.

Left: The Stylee Crew (later known as 37 Degrees), who individually all hosted shows on bFM at various stages. Clockwise from top left: DLT, Roger Perry, Stinky Jim, Dubhead, Slowdeck. Right: A 2011 reunion of bFM dance godfathers Sam Hill, Greg Churchill, and Sample Gee.

In 1993, Dominik Nola moved Cammick back to Tuesday and added The True School Hip-Hop Show with DLT, Phil Bell, Otis Frizzell, Mark “Slave” Williams and, eventually, P-Money (then a young kid from South Auckland who used to bus in every Thursday for the show). This allowed BPM to focus exclusively on house and Detroit-influenced techno. The rave show was replaced by a drum and bass show later in the decade, but the Thursday night shows formed a solid block of club shows throughout the 1990s and often outrated the daytime shows.

During the days, the playlist also reflected the growing number of Pacific soul, hip-hop and dub releases arriving on a number of new indie rhythm-based labels such as Deepgrooves, Tangata, Kog and Murray Cammick’s Southside, capturing sounds that were largely being ignored by mainstream radio. It was 95bFM that first played Sister’s Underground’s ‘In The Neighbourhood’, OMC’s ‘We R The OMC’, 3 The Hard Way’s ‘Hip Hop Holiday’ and tracks by Dam Native, Sulata, Urban Disturbance, Ermhen, and Grace.

And on Saturday mornings, Bevan Keys and Peter Urlich’s long-running show Nice and Urlich woke Auckland up to house music.

Left: Dom Nola in 1987, near at the start of her long association with Campus Radio/95bFM. Right: Renee Jones (95bFM DJ), Stephanie Cook (Fake Purr), Michelle Lowe (95bFM DJ), Jason from Anonymous Guru, Anneliese Stunzner (95bFM DJ), and their friend, music stalwart Kathryn Owler. - Photo by Tim Mason

Other radio stations are shit

Breakfast and Drive, flagships on any radio station, started to draw more listeners. Irreverent, often funny and sometimes provocative, they reflected bFM’s growing audience and were literally in tune with the times. “They had so much talent,” says Aaron “Captain” Carson, “and it was about treating the audience with respect, not as gullible children like some radio stations do.”

Newsreader Ria Keenan. - Photo by Graeme Hill

The news was delivered by a revolving team of student volunteers, using the station to learn their craft in public. Their on-air bulletins were, and remain, a long way from the polished mainstream. As likely to cover some little-known animal rights protest or an obscure incident in a faraway land as any big story of the day. Alongside these, shows like The Wire and Culture Bunker offered more in-depth review and discussion of current affairs and the arts.

Aaron Carson and Bill Kerton on a Breakfast Bus live to air. - Aaron Carson Collection

Content could switch from intelligent, insightful interviews to a competition for concert tickets. From Havoc’s much loved “What am I?” game with dozens of listeners calling in, to a debate among the team about genetic engineering, followed by the debut of a new local single such as Darcy Clay’s ‘Jesus I was Evil’. All underpinned by a varied, alternative leaning playlist mixing the best of local and international music. Authenticity was the name of the game, and the on-air competitions didn’t seem naff or corny – because they weren’t.

Darcy Clay at bFM Private Function, 29 Nov 1997, Old City Markets. - Photo by Murray Cammick

“Our presenters weren’t trying to capture a demographic,” says Harriet Crampton. “Listeners can tell when they’re being sold to by people who don’t really see them. bFM had a mindset which was driven by being interesting, being anarchic, being on point with what was new. Its presenters reflected that mindset.”

Suddenly there were car bumper stickers all over Auckland proclaiming “bFM Louder” and “bFM – Other Radio Stations are Shit”.

“We were there to reflect our people, and our people were all sorts who wanted something different, something that reflected their lives,” says Carson. “... the whole point was you might hate that hip hop song playing but then your favourite Replacements or Alex Chilton song would come on and you’d think, well maybe that hip hop song is quite good after all.”

It wasn’t all plain sailing. Havoc lived up to his name at times, testing the patience and resilience of the programme directors and station managers. There was a long-running saga where he repeatedly voiced his subsequently discredited views on the health dangers of soy-based products, and more than once said on air “that stuff is like having an old man spit snot in your mouth at a bus stop”. Sales dropped for brands like Bean Supreme and Sanitarium, the latter bringing in the heavy legal artillery. Station manager Suzanne McNicol was having weekly Friday meetings with a lawyer at one stage. While it was evidence of bFM’s growing influence, she could have done without the stress.

Mikey Havoc

Bill Kerton, who put Havoc on Breakfast when he took over as programme director in 1994 – a move not unanimously supported at the time – recounts the Karen Walker debacle. Walker’s brand was taking off. She was a fan of the station and one of bFM’s main sponsors. Havoc took to insulting her looks on air. After a meeting with management, he wouldn’t commit to never doing so again. Sales rep Josh Hetherington had the unenviable task of meeting with Walker to explain this, while trying to secure ongoing advertising spend.

Sales rep and host Josh Hetherington with the Powerstation's Carmel Bennett. - Photo by Graeme Hill

Havoc was also frequently late for Breakfast. It might have seemed like part of an ongoing in-joke for many listeners, but it drove management nuts.

Bill Kerton. - Photo by Graeme Hill

Bill Kerton started in radio as a 17-year-old copywriter in Whangārei. He arrived at bFM with a decade of experience in the commercial sector as a writer, DJ and programme director, including two eventful years with a station in Belfast, Ireland. He later left the station to direct Havoc and Newsboy’s TV show, Havoc. “I’d never directed anything on TV until the day I started,” he says.

Kerton knows Mikey Havoc well: why did he have such an impact as a host?

“He was already a DJ and part of the furniture,” says Kerton. “I just transferred him to Breakfast where I knew his high-octane delivery and genuine creativity would be given free rein. He immediately had a huge impact on the station’s fortunes. Having worked with him later in television, he is one of those incredibly rare individuals with genuine ‘X-factor’.

“He instinctively understood the power of connecting directly with his audience, making them laugh, cajoling, lampooning but always on their side, setting up their day. One thing I knew from my commercial radio background was the adage ‘win breakfast, win the day’. Mikey gained an enormous cult following and laid the foundation for bFM’s assertive role in the mid and later 90s media landscape.”

Mikey Havoc singing with his band Fontanelle, 95bFM Summer Series, Albert Park, 1995. - Chris Familton collection

The makeup of bFM’s listenership remains part of its own X-factor. On one hand as it grew bigger than its student base it became increasingly diverse and the age range started to stretch. On the other it was unified by a common outlook that’s still hard to pin down. Is it primarily about alternative and local music? Or does it also reflect the fact a certain percentage of people gravitate towards the counterculture (whatever that is these days) and independent broadcasting with “no sanitised bullshit”? All of the above, probably.

Commercial radio programmers would have had a conniption at “b” because this community was so hard to define. But as we all know, youth and/or popular culture, especially when music related, sometimes pole vaults over the accepted status quo. Liverpool, London and San Francisco in the 60s. Dunedin in the 80s. There are many examples.

Harriet Crampton: “If you had a ‘b’ sticker on your bike or a bCard it was obvious you were a certain type of person, it was like a Masonic handshake – you were part of a group which was at the tip of the local zeitgeist. I can’t even describe it really ... an intellectual, left-wing, vocal, influential young fogey loping around Tāmaki with a critical eye on the world.”

However it’s defined, bFM’s audience kept growing, fuelled by the notion that “eclecticism” was okay as long as it was cool, interesting and worthy. That’s where the intangible “being at the heart of the culture” stuff comes in, along with the need for instinctive “on the money” curation by the station’s programme directors. Of course, some listeners thought some of what was happening (music, general content, hosts) was rubbish at times. But that’s part of why it survives too. If you want safe, repetitive radio there is plenty to be found elsewhere.

At the peak of this period there were 60,000 paid up bCard holders (there were 11,000 in 2024). The bCard still provides discounts at selected retailers, concert ticket discounts and the ability to take advantage of on-air competitions. But it’s also a badge of belonging.

But it wasn’t just bCard holders. The growing audience continued to defy convenient demographic norms. They might live in a scruffy student flat or be an aspiring yuppie. Some were vegan alternative lifestylers.

They all had one thing in common. The desire for intelligent broadcasting delivered with attitude. A radio station that played The Stooges alongside a 60s soul track. Where the latest Soundgarden or Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds album was featured. Where the Mayor of Auckland or the Prime Minister would phone in for a cheeky interview on Breakfast.

On the Breakfast show you could also hear the daily Surf Report phoned in from the coast, and Jennifer Weathercentre’s weather report was really more of a morning chat between friends. The Drive show hosted its long-running Cocktail Corner, the on-air team gleefully making and consuming a different concoction each week.

The ratings game

Radio surveys, run by The Radio Bureau today, have become weekly in the digital age. Back in the decade we’re visiting they were six monthly, commercial stations loading their programming with give aways and competitions in the weeks prior.

Surveys are vital for networks selling advertising, providing data on listener numbers and demographics. bFM has traditionally not participated, partly because it sees no point in the investment (it costs to do so) and partly due to a philosophical stance of not playing the numbers game that could grease the slippery slope towards commercialised programming. That didn’t stop it having success attracting major advertisers.

The station had numbers from a late 1995/early 1996 survey and McNicol quietly sought board approval to buy another survey in mid 2001, “just so we could see once and for all what the listenership was”, she says. These offer interesting insights.

At the end of 1995 bFM had 2.5% of Auckland’s one-million 10+ (age) potential radio listeners. Six months later this had doubled to 4.4%, or 44,000 listeners. It coincided with Bill Kerton taking over as programme director, putting Havoc on Breakfast, pruning some of the specialty shows and tightening up the playlist to push music the station’s growing audience wanted to hear that commercial radio wasn’t playing.

That 4.4% figure wasn’t known to bFM at the time but the survey McNicol bought in 2001 confirmed the station was sitting at 4.3%. These ratings undoubtedly rattled some mainstream cages and hastened the arrival of the likes of commercial rock stations like Channel Z. We don’t know what happened survey-wise through into the mid 2000s, but it’s fair to assume things grew substantially given the 60,000 bCard holders and the arrival of several big advertisers – survey numbers for bFM would still have been researched even if the station didn’t pay to see them.

--