The massive success of The Exponents’ album and singles in New Zealand in 1991 and 1992 caught the attention of the senior PolyGram bosses in Sydney, and Adam Holt was offered a job as the international marketing manager for Polydor at PolyGram Australia. The job was in Melbourne and was a big step up for the young executive. Grenville Turner was also leaving PolyGram NZ and about to be replaced by Victor Stent, with whom Adam had a weaker relationship. The Exponents, too, had a mixed history with Stent.

“The band were really pissed off with me, they’d come in because of me, and then I was leaving … but Mike Duffy [who produced Something Beginning With C] was now working at Phonogram [the other side of PolyGram in Australia, who had the option on the band] and he picked them up and recorded the follow up, Grassy Knoll, and it gave them a second shot at Australia.”

Chris Knox and Adam Holt at NZ Music Month celebrations, 1 May 2008 - NZ Music Commission

In Melbourne, Adam started off in international but was taken under the wing of one of the Australian music industry’s great legends, Paul Dickson, who headed Polydor and was gradually building that part of PolyGram from scratch.

“I learned so much from Paul. He was just so dynamic and had a great history in the business – a really instinctive feel for marketing. He taught me that you make your own luck, and you do that by believing in things and going for it. I watched him with artists; he was incredible, larger than life, and so energetic. It was as if he made things happen through willpower.”

Adam Holt with Anthrax’s Dan Spitz at PolyGram, 110 Mt Eden Road, Auckland, 1990; Adam Holt backstage on the 2018 Taylor Swift Reputation tour. - Adam Holt Collection

Polydor’s time in Melbourne was short. The Sydney head office decided that the company didn’t need a second office in Victoria, and Polydor was moved to Sydney, initially into offices off South Dowling Street in Alexandria, while the head office in Millers Point, near The Rocks, was refurbished. In Alexandria, Paul Dickson asked Adam to handle local artist marketing for Polydor. This meant Adam was now working with, among others, Powderfinger and Spiderbait, and through a joint venture deal with the local indie Redeye (originally set up by retailer John Foy), The Cruel Sea and The Clouds. “It was when the whole indie-major thing came together and totally worked”

I walked into the midst of all that when I decided I needed Polydor Australia to sell OMC’s ‘How Bizarre’ to the world. I had a trustworthy friend in the right place (two, actually, as my good mate Mark Phillips had now also moved to Polydor in Australia and was working under Adam), so I made a fateful trans-Tasman phone call. I understood that I had something with potential, and it couldn’t be sold out of New Zealand without international help. Adam was an experienced friend, so after making that call, producer Alan Jansson and I hopped on a plane to Sydney. On day one, Paul Dickson and Adam Holt committed themselves to the record. When we played him that original demo, Adam very confidently said, “I give you my word, this will be Top 5 if not No.1 in Australia.”

In 2025, Adam suggests that a big part of that confidence came from Dickson:

“He had experience with Sony and CBS and had been around when Men at Work had happened, so he always had that vision. To be fair, while big in Australia, we never really got any of the indie acts we had relationships with away in a big sense, internationally. However, it showed me that a partnership involving the indie entrepreneur and the big record company was crucial. The cool sensibility that we were able to muscle up in a way.

“We also had the connections, and being in a top six market at the time meant we could pick up the phone internationally. In New Zealand, it was harder to do that, and from a personal perspective, until OMC, I didn’t really think international success was possible.”

Adam Holt and Pauly Fuemana, Auckland, 1996 - Adam Holt Collection

OMC’s ‘How Bizarre’ reached No.1 in Australia five months later, and both Adam and Paul Dickson picked up their phones to roll out the record worldwide. Along the way, it was a very steep learning curve for all of us as we navigated the industry at its most intense (and sharkish) in the United States and Europe. However, from a personal point of view amid the mayhem, Adam was always my guide.

Hence my distress when Adam decided in 1996 to return to New Zealand for family reasons at the height of ‘How Bizarre’s’ upward trajectory. Universal Music New Zealand had just been launched by the US parent (ex-MCA), and the managing-director position was up for grabs. That position eventually went to George Ash (who had been running the MCA desk at BMG), but nonetheless Adam resigned from Polydor Australia and relocated back across the Tasman. It was a courageous leap considering he didn’t have a job to return to, but Tim Read, the head of PolyGram Australasia, offered him a position at PolyGram NZ, covering marketing and working on the OMC project with me.

“It was good,” says Adam. “No, actually it was great because I got to work on the project closely, and I also got to know Pauly. We were making videos, and hopefully, I provided a bit more sanity in the record company when we went through all that, and it provided synergy with Australia.”

New Zealand only lasted a year, and by early 1997, the Holts were back in Australia, with Adam replacing Paul Dickson as managing director of Polydor Australia (Dickson moved up a notch to head the overall Australian company). By then, we were managing the massive international success of ‘How Bizarre’, trying to come to terms with marketing figures that read like phone numbers and the ups and downs of the OMC touring machine in Europe and the US. There were more videos and daily decisions to be made. Adam was on the spot and, as he says, “learning and learning all the time.”

“to do a massive international record from New Zealand, it’s a bit like the four-minute mile”

The success of ‘How Bizarre’, Adam says now, was a psychological leap, not only for us but for the New Zealand music industry.

“We were the first to do a massive international record from New Zealand, and it’s a bit like the four-minute mile. No one could do a four-minute mile until Roger Bannister did one, and then everyone’s doing the four-minute mile. Then they’re like 3.50, 3.40. It was the same thing; once we knew it could be done, you started thinking that way. But equally, we were used to dealing in $5,000 and $10,000 deals, maybe a $20,000 deal, maybe having a hit record in New Zealand. But then you’re dealing with millions of dollars on a global scale, and then that becomes your new ‘that’s what’s possible’.”

The last half of the 1990s saw Adam and his family travelling back and forth across the Tasman. The PolyGram world was upended at the end of 1998 when Edgar Bronfman – boss of the Universal Music Group – leveraged his Seagram family fortune to take over the much larger PolyGram.

“Little Universal bought big PolyGram, and I was made redundant,” says Adam. “We had two kids by then, so I was quite keen to get back to New Zealand and quietly saying ‘Please make me redundant, make me redundant,’ and they pretty much wiped out the whole PolyGram Australasian management team. I mean, no one likes being made redundant, but I was sort of happy to get back home, although I had no clue what I would do.”

The company helped him find job offers outside the industry, which he declined. However, two kids and a mortgage were an impetus, and he was aware that he needed to find something soon.

“And then my good friend, Chris Gough – another great independent guy, independent publisher and music licensor – offered me a job. Did I want to run Chris’s Mana Music in New Zealand? Sure, and I think I was possibly his first New Zealand employee. I set up a little office doing licensing and running a composers’ agency.

“I did that for about 16 or 18 months,” he says, “and again, it was awesome. Who you meet can have a big impact on your life and Chris was one of those people. I really didn’t know anything about publishing. I was a record company guy, not a sync guy or anything like that. Chris taught me a whole other aspect of the business and rounded out my knowledge immensely, Mana became a really important independent player – it became Native Tongue Music and now Concord. I have a huge admiration for Mana and for Chris, but also a huge amount of gratitude, too, because I was on my arse a little bit, and he really helped me out.”

Ironically, the office was in St Benedict’s Street, Newton, a few hundred metres from Universal Music NZ, headed by George Ash.

“I was in touch with Universal regularly because I was doing sync deals with them. I would be in there a bit, which allowed me to get to know George and a few others from the Universal crew. I had a really good relationship with them. George was then promoted to head Universal Australia in 2001, and they were looking for someone to head the local company. I remember bumping into George in Stables Lane [behind Universal NZ] one lunchtime.”

The Universal NZ staff with U2, 2010; Adam Holt far left - Adam Holt Collection

Adam asked him who would replace him, and George replied that his Australian bosses were considering approaching Adam. He went for an interview and was offered the job of managing director of Universal Music NZ.

“I was out for about 18 months and then came back to the job I had always wanted.

“That was 24 years ago, and chapter two started. But chapter one was amazing because it was bands, clubs, record shops, Festival, PolyGram, Australia and Mana. It had been a huge learning curve, but over the years I had met industry legends such as Michael Gudinski, Harry M Miller, Benny Levin, John McCready, and Peter Dawkins – these really creative, driven people who inspired you. By the time I came into Universal, I’d had a really good education, and I felt like I knew what I was doing. I felt a lot more confident coming in. Not being arrogant, but I just thought, yeah, I’ve been around a while, and I know the business. I felt ready for the challenge.

“I also came in at the absolute peak of the record industry.”

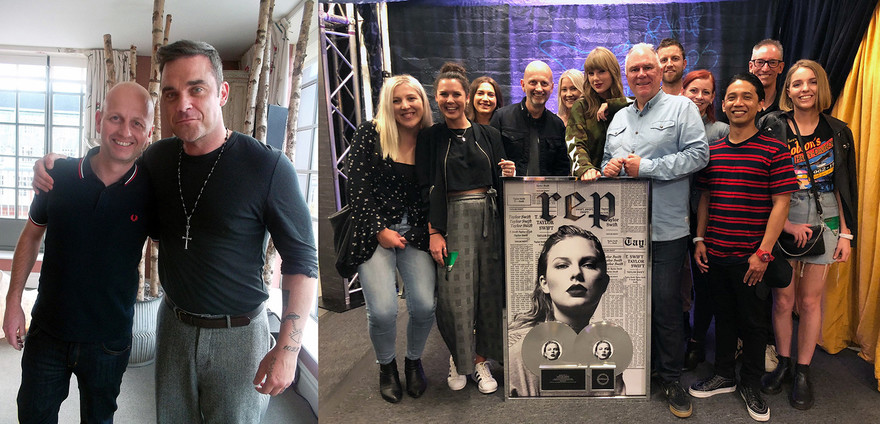

Adam Holt and Robbie Williams, 2015; Adam Holt and the Universal NZ staff backstage with Taylor Swift in 2024 - Adam Holt Collection

It may have marked the peak, but the global music industry was also about to go off a huge cliff, a collapse that pundits suggested might be terminal. The advent of the MP3 and pirate file-sharing sites such as Napster led to a rapid decrease in compact disc sales, leaving major labels in disarray worldwide.

Adam admits, “The annual New Zealand industry wholesale figures as we talk today still haven’t beaten those of 2001”.

Investment in new artists and A&R development was increasingly risky but still an essential part of the process. Record companies must invest in the future to survive, no matter the current climate. New Zealand was no exception.

Sheryl Crow and Adam Holt, Sydney, late 1990s; Universal’s Alister Cain and Adam Holt with Stevie Wonder, 2008 - Adam Holt Collection

“I came into Universal and then immediately went on this absolute roller coaster of a ride through the piracy era. We were signing acts and having some local success, while watching business is just falling away from us. It was a crazy journey navigating our way through the biggest changes the music industry had ever been through, while desperately trying to maintain our investment in artists and A&R. I knew it was vital that we kept that part of the business alive. It got rough at times but with the timely dawn of the digital era, our luck began to turn around. We surfed that dip and then the rise.”

Adam Holt and Hayley Westenra, 2016 - Adam Holt Collection

Adam inherited what is still one of Universal NZ’s most significant A&R signings, a young crossover classical vocalist from Christchurch, Hayley Westenra. George Ash had signed her to Universal NZ and released two albums locally, but Adam could see Hayley’s global potential. He says, “We really had to take Hayley to the world because everyone knew she was pretty special and had that potential.”

Hayley Westenra in November 2003 with the Universal NZ staff and Prime Minister Helen Clark - Adam Holt Collection

After consulting with Hayley and her parents (she was still in her early teens), Adam struck a partnership deal with UK Decca classical boss Costa Pilavachi: “a great, great music man”. Hayley’s third album, Pure, was released in 2003. A mix of classical, pop, and waiata, it became a global sensation, both critically and commercially. Upon its release in the UK, it became the fastest-selling debut album in the history of the UK classical chart and sold over three million copies worldwide.

Universal’s first local A&R deal under Adam was a partnership with the fast-rising South Auckland hip-hop and Pacific soul label, Dawn Raid.

“I started in July 2001. I walked in on my very first day, and this kid was standing at the back of the room. I was meeting everyone, and it wasn’t until the afternoon that I went over and said, ‘Oh, who are you?’ He replied, ‘I’m Andy from Dawn Raid, and I’ve been waiting to see you’. He knew the new boss was coming in, and it started a pretty amazing relationship.

“Andy and Brotha D had been having sketchy talks with George [Ash] about a deal, but they hadn’t nailed it or signed anything.

“Earlier, when I was doing some sync work with Mana, I had been trying to find a Dawn Raid track, and was asking who is this label Dawn Raid? I called Real Groovy Records and asked if they knew of them. They said, ‘Oh, yeah, they come in every few months with a batch of CDs, and we buy a few of them. We haven’t got their number or anything like that.’ So I knew of them, and I knew that they were entrepreneurial, and, yeah, there was Andy in our offices on day one, waiting for me.”

The pair hit it off immediately and worked out a distribution deal which opened the door to a decade of massive successes with the groundbreaking label, not just in New Zealand, as local hip-hop exploded in 2003, but worldwide, as Dawn Raid signed deals with Universal’s labels in the US.

When I asked Adam about his career high points, the first thing he mentioned was his next signing.

Elemeno P’s Dave Gibson with Adam Holt of Universal Music NZ - Adam Holt Collection

“I asked Grant Kearney, who was [Universal] A&R, to give me all the demos he had, and he gave me a whole pile. One tape that immediately caught my attention, and I thought, ‘I love it,’ and signed them straight away. That was Elemeno P.”

Not everyone was convinced.

“There were a few doubters; the industry was a bit sniffy about them. People thought they’d been put together by the label, but they hadn’t been. They were just a really cool band. They were real, and it was the height of that pop-punk thing. But more than that, they were special. They were great songwriters, and Dave [Gibson] was, and is, a magnetic and charismatic person who single-handedly became friends with the whole music industry.”

Before the band’s debut album was released, the record company led with a string of singles, ‘Every Day’s A Saturday’, ‘Urban Getaway’, ‘Nirvana’, ‘Fast Times In Tahoe’, all of which received substantial airplay, but Adam felt they needed one more.

Brendan Smyth from NZ On Air and Adam Holt at the launch of Elemeno P’s Trouble In Paradise album, 2005 - Adam Holt Collection

“I said, we need a couple more tracks, you know. Sorry to do this to you. And then they went away and came back and gave me ‘Verona’, which was the big, big cut-through track. I said, ‘I think we’ve got it. I think we’ve got the track.’”

The band’s debut album, Love & Disrespect, was released on 3 July 2003. It debuted at No.1 and has, to date, been certified triple platinum in New Zealand.

An awards ceremony for Gin Wigmore’s 2009 Australasian smash album Holy Smoke. Gin Wigmore, fourth from right; Victoria Blood, second from left; Adam Holt kneeling centre. - Adam Holt Collection

The A&R successes continued. The Bleeders, signed in 2006, had a gold album with Sweet As Sin; Gin Wigmore (both her solo releases and the 2009 pairing with Smashproof, which produced the single ‘Brother’, which topped the charts for 11 weeks, the longest continuous run at the top since our charts began); distribution deals with expat New Zealand music exec Kirk Harding’s Move The Crowd label; Marlon Williams, The Phoenix Foundation, Beastwars and Six60, whose hundreds of thousands of sales in the past decade was essentially done via the same deal he worked out with Dawn Raid at the start of Adam’s Universal years.

“That was the archetypal indie-major partnership, one that I treasured and still exists today. I’ve always felt responsible as the biggest label that your job is to support the industry and lift people up. If you get given a job like this, it’s a real privilege, and you want to make sure you do good things with it. You can be an arsehole, or you can make a difference.”

Part of that responsibility arose when, in 2012, Universal NZ acquired the rights to the EMI New Zealand catalogues through a global takeover. EMI’s vast repository of New Zealand music, combined with the other catalogues the company already owned (Polydor, Vertigo, Philips, Pye, Tanza, pre-1975 RCA, and Allied International), was significant. Given the way the industry operated in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, much of that music was originally released on 45 singles and has since become largely unavailable.

Adam and former EMI boss Chris Caddick devised an incredibly ambitious plan. While physical reissues were out of the question, the arrival of digital distribution made it viable to put everything online if it could be sourced. Furthermore, each artist would be given a new contract with greatly improved royalty rates and would be paid, many for the very first time. With Chris leading the charge and Adam providing both the distribution and the financing, the project took over a decade to complete. Few of the acts will have made much money from the reissue of their often-limited number of recorded tracks, but some have.

“It’s a cup of tea in terms of royalties at the end of the day for most of the artists, but the tracks are now there, and people can now find this great legacy of New Zealand recordings to enjoy. The project was never really about money, it was about respect to the artists and the industry that came before us. But equally, you never know what might happen once they became available again. We did a US$10,000 sync for [60s folk band] The Southerners a few years ago; they would never have got that if we hadn’t done the reissue program. The bottom line for the future is that it’s now been done. Chris obviously did all the hard work on the project, and he should be absolutely applauded for it.”

“In a job like this, you want to make sure you do good things with it. You can be an arsehole, or you can make a difference.”

What made it possible was the same thing that enabled much of the A&R and local artist successes in the last years of the 2000s and the decade and a half that followed: digital and streaming.

Apple launched the digital library iTunes in April 2003 and then set out to sell it to record companies, many of whom were initially resistant but were on board by the time another service, Spotify, entered the digital music game in 2009 as a streaming service in the UK, followed by the US in 2011. New Zealand followed in May 2012, and other services entered our market thereafter. A combination of them, but especially Spotify, iTunes (which launched its streaming service, Apple Music, in 2015), and YouTube Music forever reinvented the game. If the arrival of the MP3 posed significant questions about the future of the entire music industry, streaming – despite all the controversies surrounding it, provided an answer that was firm (and, to some, profitable). Despite the resurgence of physical formats, especially vinyl, the answer remains streaming.

“In 2004 I had to fight to continue investing in New Zealand A&R because at that low point in the industry there was so much pressure on the business. I had to make the company a bit smaller, and run a tight ship to control costs but luckily, I was supported on staying in A&R. We got through the tough times, and then iTunes came along, and the stabilisation of the business began.

“And again, I love change, and I’ve always had this philosophy: Don’t be scared of change; just run towards it and grab it. I was very progressive with digital. I worked really hard with Apple and then subsequently with Spotify to grow the digital business in New Zealand. I always said if this is the future then we’ve got to get our heads around it and own it. By 2011 things started feeling a little bit better again. There was still a long, long way to get back, but then we got to 2012, and two things happened …”

The first was a demo tape.

“Scott MacLachlan [then Universal’s A&R manager] and I were separately sent this tape of Ella Yelich-O’Connor performing at her school,” says Adam. “I called Scott and asked, ‘Have you seen this? It looks pretty interesting.’ He loved it and said, ‘Leave it with me.’ Ella and I have laughed about it since, but she came into the office with her mum and dad, Sonja and Vic, but hardly said a word to us. I didn’t know what she was thinking, but we could see she had something special. From there, we started her off on a development programme that Scott put together and ran. That long-term development helped Ella figure out what she did and what she didn’t want. The rest is history.”

Lorde presented with a RIAA Diamond Single Award for Royals by Monte and Avery Lipman at Republic Records’ Grammys afterparty in New York, 2018. Adam Holt second from left. - Adam Holt Collection

The story of Lorde’s pathway to success is well documented, particularly her decision to post a song called ‘Royals’ on her private Soundcloud account, despite nervousness from her record company. This song quickly virally skyrocketed around the world, especially in the world’s biggest music market, the United States. As a result, the US Universal operation came knocking. This prompted Adam to make a quick but possibly dangerous decision. Traditionally, when an artist seemed poised for international success, the small New Zealand company partnered with a larger offshore branch with deeper pockets. This was the case with OMC (in the pre-mass-internet and digital era, I had no way to fund or market a local act in the US or Europe), and again, Dawn Raid had partnered with the US Republic division of Universal, Hayley partnered with Decca, and even Gin Wigmore was signed with Island Records in Australia.

This time it would be different.

“There was a moment when I thought, this is going to get so big, I don’t think we can handle it, says Adam. “I was about to do a deal with Republic, where they would take a share of the project. But at the last moment, the great Andrew Kronfeld, [executive vice president] at Universal, said to me, ‘Take a breath. This single is huge. I think you’ll be okay, and we’ll back you if you need it.’ While we never needed that help financially, Andrew supported us with international staffing through the Pure Heroine campaign. In retrospect, I can see that was a critical moment for the New Zealand music industry. It was certainly a pivotal moment in my career.”

Adam Holt with Max Hole (CEO of Universal Music International), Lorde and Sir Lucian Grainge (Chairman of Universal Music Group) at the Universal Music Group 2014 Grammys after-party in Los Angeles; Adam Holt at a PolyGram conference, Australia, 1993. - Adam Holt Collection

And so Universal New Zealand, from an office in Newton, Auckland, managed and drove one of the most significant global music stories of the past decade at a business level, working directly with the artist.

“After OMC, I wasn’t a total stranger to global success, but not that level of success. This was a whole other thing, and it changed everything. It changed the New Zealand company, and it changed the relationships and connections I had with people around the world. To this day, we work directly with Lorde, and I am very, very proud of that.”

With the success and millions of sales for Ella came company pressure. Multi-national record companies operate with regional budgets, and the only way is usually upward. If a company like Universal NZ achieves a massive success in one financial year, then it’s expected to grow that result the following year. This is much easier in a large company division or territory with a depth of A&R to draw on, but for a territory the size of New Zealand – where there is at most one internationally successful act each year – an act like Lorde inevitably blows the budget out.

Was there pressure after ‘Royals’ and Pure Heroine?

“Yeah, yeah, absolutely. Growth is expected every year, especially when you’ve got a big star on your roster. It was my job to protect Ella from that pressure and give her time to develop her next phase at her own pace. Initially, Melodrama obviously wasn’t as big as Pure Heroine, but over time, it’s become a bigger record culturally than her debut.Economically, it’s still Pure Heroine largely because of ‘Royals’, but ‘Ribs’, amazingly, also off the first record, is one of our biggest streaming tracks now. I think Melodrama was where Ella fully realised her vision about who she was, and when everyone suddenly went, oh, my God, there’s something really special here.”

However, Lorde wasn’t the only massive success coming out of Universal NZ in the second decade of the 21st century.

Around the same time as he’d heard Ella’s demo, Adam was watching television one evening and …

“I saw these two young Samoan boys [Pene Pati and Amitai Pati] singing opera on TV,” he says. “Because of my background with Hayley [Westenra, and his experience in Australia marketing Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Really Useful Group in that country], I knew the market was there, but I also knew they were really, really special. We tracked them down, discovered [third member] Moses [Mackay] was part of their group as well, and we signed Sol3 Mio.

“In that same year [2013], we released both Lorde and Sol3 Mio. Obviously, ‘Royals’ was globally huge, as was Pure Heroine, but Sol3 Mio sold more than Lorde in New Zealand that year and since. I don’t know what the Sol3 Mio first record is up to now, but it’s something like 11 times platinum.

“We went from navigating through this terribly tough time, and then suddenly, we had these two huge things happening, both of which were phenomenal. It was just the most heady, heady time.”

It’s been three and a half decades in the music industry, so I had to ask the question: out of all the records you’ve released, A&R-ed, and mentored, which are you most proud of? There was a long pause and a quiet, considered response.

“Oh, oh, I gotta be careful on that one…

“Okay, here’s the one I’m probably most proud of: we had a number one single with this song for the SPCA. One that you couldn’t hear; only dogs could hear. And it went to number one. I thought, okay, now we can do anything.”

Another silent pause.

‘It’s pretty hard to go past Lorde. That first record was life-changing for her and us, and for New Zealand, and then critically, Melodrama as well. But there are so many artists I love. We only distributed it, but I love the first Cut Off Your Hands record, and it’s still on my playlist. Elemeno P, of course. I feel so close to that.”

As he remembers, he smiles. These are not records, they’re lifelong friends.

“we had a No.1 single with a song for the SPCA. One that you couldn’t hear; only dogs could hear it”

“I gotta say [The Exponents’] ‘Why Does Love ...’ is where it started, too. To actually have the first record you ever made in the record business become this sort of unofficial New Zealand anthem. That’s pretty good, you know. So yeah, that one.

“And then How Bizarre’. Being involved in ‘How Bizarre’ is still just like, wow.

“I’m so proud of those, but it’s weird looking back. In this job, you tend not to look back, you tend to look forward, you ask what’s next? That’s your job. Success is great, but it’s in the rear-view mirror.”

I tell Adam that one of the defining things about Lorde for me was that it sounded like an indie record, albeit one released by a major record company. It has an indie soul, if you will.

“Lorde’s US management have always very complimentary about Universal New Zealand for that very reason. They say working with us is great because even though we’re a major label, it’s like working with an indie. We can offer boutique, personal service while still having the ability to scale up a release globally using the global muscle that UMG has, especially in the US. But you know, the spirit of the New Zealand company is hands on, caring and personal, and it’s inspired by small independent labels like Dawn Raid and Propeller.

“I think what has really driven my career, especially my major label career, is understanding the passion of independent labels, and their willingness to take risks and give artists chances. I try to apply the same approach.”

“It has been amazing watching Ella grow, and her artistry continues to bloom. That’s the thing – she is a true artist, she does everything on her terms. We’ve worked really hard to always protect that independence for Ella. I mean, she would accept nothing else, because she truly knows who she is and what she wants to do, but having the honour of supporting her through these last 12 years has been just ... it’s just the absolute pleasure and pinnacle of my career.

“It’s not a great analogy to use in print, but in curling, you have someone who puts the stone down the ice, and these other people who sweep in front of the stone while it’s moving to smooth the path ahead. I’ve always felt that Ella throws the stones with brilliant accuracy and we’re the ones sweeping the path for her.

“I love the business, and I love record companies, and I love what I did, but that’s ultimately what anyone in the business wants, that global success. To actually achieve it with Ella was dream-come-true stuff, and even better, it wasn’t like it was a one-off or a one-hit wonder. She was the real thing. She’s absolutely incredible.”

The last years of the 20th Century and the early 2000s saw New Zealand take its music to the world, but we almost always did it in the most unusual ways, often with the most unusual music. Lorde is just the most successful example of an antipodean tradition of success beyond our shores, with unique music.

“We need things like Lorde, which are different, interesting, and unique. There’s no point in us trying to export coal to Newcastle. OMC was this breath of fresh air and, if you see Flight of the Conchords on TV, you go, what’s that? That’s weird, and I think that’s a strength. That’s what Flying Nun did, too. It’s not about chasing the latest trends or anything like that, but just finding the odd ones, the unique talents that have something different for the world, and really, really supporting them.”

Adam Holt and the late Kirk Gee, from the social pages of ChaCha magazine, 1984; Lisa and Adam Holt with former EMI Australia managing director John O’Donnell and his partner Sue, 2018 - Adam Holt Collection

For the last 24 years, the kid who came across the bridge with a garage band in 1980 has mostly been just a few short metres from addresses with significant personal history. Universal Records NZ is located in the small, as the name suggests, colonial-era Stables Lane, just behind the old shophouses and early 20th-century buildings of Symonds Street.

“I still love walking down that lane, looking at the Edinburgh Castle Hotel, where we, the Meemees and all the other bands played. Next to it is [Neil Finn’s] Roundhead Studios; down Symonds Street was Russell Crowe’s Venue, where Sons In Jeopardy often played; we’ve got The State Theatre where I saw The Terrorways. Up the other way is The Powerstation, which used to be The Galaxy and The Asylum.”

At the last venue, a quiffed young man would often be seen throwing himself around the stage to the sounds of the Beastie Boys, a few hours before he had to open the doors on a Queen Street record shop and sell their records. It’s a life in music and a life of musical passion.

In the music industry, the phrase “a record person” is really the highest compliment. It doesn’t imply age but rather a desire to sell music for the music’s sake, using an instinctive grasp of the machinations of record companies and the market. To do right, for the right reasons, by the artist and the record company. Think of Chris Blackwell, Martin Mills, Sylvia Rhone, Michael Gudinski, or Clive Davis. They are incredibly rare. In my years in the New Zealand industry, Adam Holt is probably the purest example of an old-school record man I’ve ever known. I’ll leave the last words to him.

“I always had this philosophy: if you lift others up, you win, because if they succeed, I succeed too. Obviously, you’re in competition with the other labels and all that sort of stuff. But yeah, it’s really about building that community and a place artists want to be. Then we all win.”

--

Read Adam Holt, part one: Class of 81, school bands, The Screaming Meemees, record stores and The Exponents.