Bennie Gunn, jazz pianist, stops on the Desert Road beside a plywood car he built, on his way to join the Auckland scene in 1957 - Bennie Gunn Collection

In 1957, aged 24, Wellington jazz pianist Bennie Gunn left his job as a radio technician at the New Zealand Broadcasting Service and headed to Auckland with the intention of becoming a professional musician. His mode of transport reflected his adventurous nature and his “popular mechanics” skills: he drove up in a sports car he built himself out of plywood.

Gunn quickly befriended the leading young jazz players in central Auckland, and began performing with them in small clubs around the city. Many of them lived together in the notorious musicians’ house at 57a Symonds Street. All the while, he continued his craft as an electrical technician. In the basement of 57a he built a large ham radio set, and began making amplifiers. Before long, he formed his own manufacturing company, Concord, which supplied amps to many aspiring rock bands in the 60s and 70s.

The Gunns were a musical family. Gunn’s mother Dorothy (née Hanify) was a pianist who gave recitals, performed on radio, and taught music. Gunn was born in 1933 and followed in her footsteps. He told Chris Bourke, in a 2009 interview, “When I was a little kid I sort of observed this crawling around on the floor at home, she had particular pieces that I grew to like particularly well, particularly Chopin, some of Beethoven’s stuff, and Mozart. I sort of absorbed this as osmosis. It’s almost as if I was able to play that stuff with much less difficulty than I would have expected.”

When Gunn was six the family moved from Wellington to Invercargill, where his father was offered work (and his mother organised radio programmes on 4YZ). Gunn learned piano, played in the competitions, and joined the college dance band when the family shifted to the Hutt Valley in 1947.

Llew Arnold's School of Modern Music, Lower Hutt

At the age of 14, Gunn would sit with a wind-up gramophone on a golf course near their house learning Woody Herman and other 78rpms after an uncle gave him a clarinet for his birthday. His mother taught him piano, and from a book she gave him about boogie-woogie piano he learnt the boogie bass lines and matched them with some two-part inventions by Bach in the right hand. “They fitted together perfectly,” Bennie recalled. “It was an astonishing discovery. Bach was the first jazz musician that I knew of.” His mother wasn’t happy about it, though, and soon Bennie was with a different teacher, Llew Arnold, who was open-minded to jazz.

Gunn's schoolfriend Bart Stokes, Hutt Valley saxophone prodigy

The band at Hutt Valley High School was “pretty terrible” but included saxophone prodigy Bart Stokes, who was only a couple of years older. “We did a lot of playing together. Bart was most unsatisfied with that band and caused all sorts of ructions. We formed a group and played at local dances, as you do.”

They played “the usual stuff”, starting with Fats Waller’s ‘Alligator Crawl’ “and progressing from there.” Another influential piano tutor was multi-instrumentalist Bill Hoffmeister; Gunn would arrive straight from school in short pants. Hoffmeister encouraged him to perform in public, and soon he was playing with well-known local names such as Don Richardson, Ken Avery, and Vern Clare.

Visiting Americans turned up at jazz club evenings in Cuba Street. “They played some astonishing stuff. So bang on and precise, it’s electrifying. Playing with people who are tremendously talented sort of lifts your game. If you get that chance you rise to the occasion. You have to.”

Bennie Gunn's Blue Rhythmaires, 1949; Gunn is at the far right - Bennie Gunn Collection

In Wellington the Majestic Cabaret broadcast weekly concerts with musicians rotated between orchestras assembled by Don Richardson and Vern Clare. The repertoire ranged from pure jazz to commercially orientated pop. “It’s a difference between what you have to do and what you want to do. It’s only in recent times that I’ve been released from that necessity because I don’t have to go and play stuff that I find irritating and pointless. That’s why I’ve long since given up playing dances and 21sts, particularly weddings and so on. It’s the sort of thing that would drive you completely nuts. Unless you enjoy it, it’s not worth doing.”

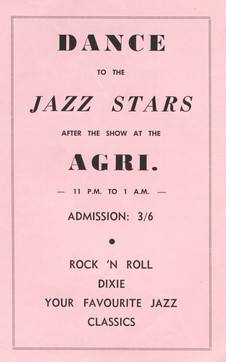

In the early 1950s Gunn performed with his groups – a trio, a quartet – at jazz concerts in Wellington’s Town Hall, and began venturing further afield. In 1955 The Bennie Gunn Quartet played at the One Night Stand jazz concert at the Auckland Town Hall, and in 1956 performed at a jazz concert in New Plymouth. The local reviewer wrote, “there is no doubting this boy’s keenness and versatility.”

Agri Dance, New Plymouth, 1955: "There is no doubting this boy's keenness and versatility."

Moving to Auckland, Gunn met more big names such as Crombie Murdoch and Nancy Harrie; he checked out venues such as the Civic Wintergarden and the Peter Pan, the Orange Ballroom and the Crystal Palace. He performed with the Pem Sheppard Band at Tauranga during the summer of 1957-58, and with the Pete Shaw Band and Alan Levett Group back in Auckland. At the Waiwera Hotel in the early 60s, Gunn led a band that included top players Bob Ewing on bass, drummer Lachie Jamieson, and acclaimed saxophonist Colin Martin. Bennie sang, played piano and “electric accordion”.

He recalls driving out to the El Dorado nightclub in Papakura in Bart Stokes’ Morris Minor in the early 60s, with a set of drums, a bass, and Stokes’ saxophone on board. “Before the motorway, that was quite a mission to go that far. But nonetheless, that was what working was.” The Auckland after-hours music scene evolved, as nightclubs and up-market restaurants started to open and employ small line-ups: The Back of the Moon, The Dutch Kiwi, The Toby Jug, Pine Song.

Gunn took a room in a big, central city house at 57a Symonds Street, which had been a notorious musicians’ bolt hole since the late 40s. Also living there at the time were saxophonists Bernie Allen and Pete Robson, pianist Val Leemon and bassist Lyn Christie. Allen was organising a big-band line-up, with rehearsals each weekend. “They used to come down there every Sunday morning, hung over, in various states of repair,” he recalls. “That’s where they got the core of their talent from.”

Bennie Gunn on guitar, 1950s, and his ham radio set at 57a Symonds Street

While at 57a Gunn built a big ham radio set, rewired the house’s electricity to the tenants’ advantage, and began building amplifiers and electric guitars. Residents at 57a were down to “about five pounds between us” when Gunn decided to build amplifiers. His first job was assembling and installing a public address system in the La Boheme restaurant on Wellesley Street, a former steakhouse. Gunn worked all hours at 57a, sometimes starting some carpentry about 2.30am after a gig. His hammering noise soon woke the neighbour and the pair exchanged fisticuffs.

Amplifier manufacturing would become a business when Gunn established his own company, Concord. He drew up designs and started a production line in the basement at 57a; his workforce he recruited from musicians hanging about between gigs. (Among them was Glyn Tucker, who worked at Concord long before opening the Mandrill recording studio in Auckland.)

Another project, inspired by Gunn’s wife Ces (née Celeste Howard-Smith), was the Swing Club at the Royal Empire Society club rooms in Queen Street. Visiting performers included Ella Fitzgerald and June Christie, plus locals such as Alan Broadbent and Bart Stokes. “They’d just come up and blow all the time. Then we opened it up to the public because we needed some money to pay the rent. Remember that nobody had money in those days.”

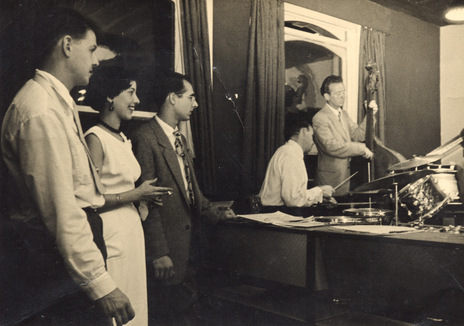

Watching from the wings at the Stork Club 1950s: Bart Stokes, Ces Howard-Smith, Benny Levin; Bob Ofsoski on bass, Bennie Gunn out of shot. - Bennie Gunn Collection

Not long after arriving in Auckland, Gunn tried teaching aspiring musicians, but found he was “temperamentally unsuited” to teaching. One pupil wanted to be a bass player, and Gunn walked him through the positions, taught him the scales and how to move between arpeggios. Half a term later, the pupil quit: he had joined a band. “What do you mean? You got a job? You can’t even play!” The pupil was joining Johnny Devlin’s band. Well, that’s okay, thought Gunn, with a jazzer’s attitude to rock’n’roll: musicianship wasn’t required.

Another wanted to play jazz piano, and his favourite player was Oscar Peterson – Gunn’s favourite, as well. The prospective pianist hadn’t played before and was prepared to practise for nine months to play like Peterson. “He didn’t last long.”

In the early 60s another generation of venues and musicians emerged, at Auckland clubs such as the Embers, the Morocco, the Montmartre. Performers included pianists Mike Walker and Mike Nock, singer Tommy Adderley, drummers Don Branch and Lachie Jamieson. After the Korean War, Jamieson had lived in the United States and learnt the new style of bebop. Deported after several years, he moved into 57a, painted his room black, and ramped up his drug habit. “The shame of it was that Lachie was a damn good drummer and changed the whole drumming scene. He was out of the Art Blakey school which had never been heard in New Zealand. He played that way and played damn well.”

The jazzers’ haven at 57a Symonds Street would survive several eras as a musicians’ crash pad

Gunn was recruited to play on national tours by the Howard Morrison Quartet, and backed visiting American performers including Dee Dee Sharp, Ben E. King and Gene McDaniels (“an outstanding musician”). In New Plymouth, McDaniels and his piano player Mike Melvoin (father of Wendy, bassist for Prince in the 1980s) caught influenza and Bennie was dragged out on piano. “It was quite a considerable challenge because of the way he played, the sophistication and arrangements – everything he did was absolutely stunning.”

Mostly, Gunn dreaded the rock’n’roll repertoire. “The music was corrupting everything that we thought was good about music and jazz, even commercial music. It was loud and pointless, ludicrous.” Nevertheless, he had to play it occasionally, albeit reluctantly; on one tour he was required to play violin and throw sausages into the audience. Another moment featured bass player Galvin Edser playing his instrument upside down while Bennie played piano with his bare feet. “It was corny, most of it absolute crap, but there is quite a lot of damn good rock music if you look for it.”

The jazzers’ haven at 57a would survive several eras as a musicians’ crash pad. A place for wild parties, meeting of like minds, and cutting-edge music. “It stayed there until everybody moved out. The Health Department took over and demolished it in the end.”

Gunn later formed a quartet, playing trumpet himself, with Lachie Jamieson on drums and Jimmie Sloggett on saxophone (recruited from the Gene McDaniels tour). But their repertoire was regarded as not suited to school socials. The inevitable demise of the jazz era and the quartet came as radio stations and tour promoters, such as Benny Levin and Harry M. Miller, moved into pop music and electric guitars.

In the 1960s Gunn hired guitar instrumentalist Peter Posa to promote Concord amplifiers, and during the guitar boom of the 60s, sales increased toward 1000 a year in New Zealand; demand spread to Australia and the Pacific.

Throughout his long career as a manufacturer, Bennie continued performing in many different combos, and he began writing songs, jazz pieces, and came third in a competition for classical composition. One song that did well in TV’s Studio One competition was ‘Tears Behind Her Smile’, which was one point behind the leading song in 1970; the following year he entered a Sinatra-style ballad, ‘Everywhere I See You’.

“I had regular gigs, all over the show,” he recalled to Bourke in 2025. “Generally playing every Saturday night, sometimes during the week. One was at Waiwera – the hotel there – and after we finished playing at midnight, we’d stay on and have a jam session. As a result we never got home until after about two in the morning.”

Early in the 60s, Gunn was a member of the Bart Stokes Quartet, with drummer Ray Edmondson and bassist Galvin Edser. “I played with Bart all the time, right up to when he died,” said Gunn. “he was a great tenor player, one of the best I ever played with.”

Bennie Gunn's jazz peers at Mt Maunganui, 1957. From left, Bruce McDonald, Bart Stokes, Greta Greer, Merv Thomas, Benny Levin, Bernie Allen. - Bennie Gunn Collection

As a teenager, Stokes was hired for some of the best gigs in Wellington, and he was only 20 when he led his own big band in a live broadcast on 2YA in 1952. Stokes was an early proselytiser of bebop, and for several decades was a professional player and arranger overseas. He died in Auckland in 2014, aged 82.

For 50 years, Gunn’s combos included the veteran bass player Bob Ewing. “I have played with other bass players since then, but none for as long. He could adapt in any way; he’d follow what you were doing and never put a foot wrong.”

Over the decades Bennie has also made many jazz recordings using his own equipment. An early example featured the Kahi brothers (Mark and Tommy) accompanying Mavis Rivers singing ‘How High the Moon’, recorded on an old tape recorder at Mount Maunganui. Lachie Jamieson played brushes on an upturned beer carton. Other recordings included pianist Bill Coleman, and a live concert by Tommy Adderley in a hall at Titirangi. Examples can be heard at Gunn’s website, Bennie Gunn Jazz.

Bennie Gunn at the Gables, 1990s (photo by Dennis Huggard), and in the 2000s

Gunn celebrated his 92nd birthday in 2025; for over 65 years he has been married to Ces, a jazz aficionado when they first met in the mid-1950s, and to this day. Most days, he can be found playing his piano or organ – sometimes with his grandson, Auckland musician Max Gunn – and he often makes recordings in his home studio in a retirement village on the North Shore. “I’m still writing,” he said in 2025, “either songs or piano solos – not with singers, mainly. I’ve written a hell of a lot of tunes, though most of them never get any further.”

Gunn’s renaissance-man career – as performer, composer, songwriter, and instrument and amplifier manufacturer – has seen him make a substantial, if often unsung, contribution to New Zealand music.

--

Bennie Gunn’s Concord Takes Flight