In the late 1980s, Doug Rogers made his move to the United States. While he still had business and music interests in Auckland, he knew that his future probably lay in the US. Much of the music industry was in Los Angeles, so that city made the most sense as a home. Over the next decade or so, he, his wife Lisa, who had been on this long journey with him, and his family spent time in both New York and Hawaii before finally settling in Los Angeles.

Doug Rogers' EastWest Studios, Los Angeles. This is Studio One, which was originally Studio One at the old Western Recorders.

“I have this kind of love-hate relationship with LA,” says Rogers. “I went twice, the first time was in 1984, but I came back for the Spinnifex deal. And then we left New Zealand permanently around 1987. We spent about a year in Australia, then to LA and I’ve been sort of bouncing around the States ever since.”

The Harlequin connections opened immediate doors for him in LA. “I was working for Kent Duncan [Kendun Studios] when I was there in 1984 and again in 1987. I’d first met him when we did the recording school [at Harlequin in 1981-82]. A total genius who redefined the LA recording scene, and with his partner Tom Hidley, designed hundreds of studios worldwide.”

Sample this

One of his last Harlequin projects was the debut album from Auckland band Fan Club. Rogers took the tapes up to Los Angeles and was mixing the record at Can-Am Recorders in Tarzana, using, in part, the sampler technology then available: the Akai S1000 and Emulator 3. However, there was a self-created glitch, albeit one that opened a door which would change his life forever.

“Producers at the time were using ‘sample reels’ to collect sounds from various sessions, which were then used for drum replacement and such,” says Rogers. “However, I’d forgotten to bring my tapes from New Zealand so I looked for some available samples in LA and couldn’t find any. With the new era of hardware samplers upon us, it seemed ridiculous that no sounds were available commercially to feed them, like a computer with no software.”

Realising he was unlikely to be the only producer or musician who required a service like this, he sensed an opportunity. It was also the era just before sampling copyright laws had been defined – in 1986, the biggest-selling album in the USA, the Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill, had largely been built around uncleared samples, so far without issue.

Rogers told the UK Sound on Sound Magazine in 2013, “People were sampling bits of records, and it was looked down upon by a lot of people as a kind of stealing, but I could see it coming. It was as clear to me as the shift from typewriters to computers. That’s where instruments were headed, too.”

Doug Rogers, The Pop/Rock Drum Samples

With all this in mind, he created a CD with drum samples and pressed a number of these to sell, releasing it locally on 24 March 1988. The Pop/Rock Drum Samples was the first commercial drum sample collection to be released by anyone anywhere, and was issued by a new company he’d just formed, EastWest Communications.

“The name sounded global,” he says.

However, musical instrument stores told him that they didn’t sell CDs, and record stores said they didn’t sell professional audio products,” so Rogers placed an advert in a local newspaper, The Recycler, and people began to ring. He followed with ads in local specialist music papers, getting a similar result. Encouraged, he went into The Guitar Center store in Hollywood and asked if he could put a box of the CDs, priced at $99 each, on their counter. “They said, ‘Fine, we’ll call you in a week or so, and you can pick up the ones that are left over.’”

Instead, that afternoon, they rang asking for more – EastWest was on its way.

Drums, more drums, bass and piano

Rogers, however, also understood that if the product was to have credibility in the industry, he probably needed a name – some star power, if you will – to raise the profile of the brand. With that in mind, he made a list of the engineers he thought captured the best drum sounds professionally. At the top of that list was legendary US engineer and producer Bob Clearmountain, a man with a CV dating back to the early 1970s. Having worked with The Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney and David Bowie, Clearmountain is one of the most successful recording engineers in the world.

“I figured I’d start at the top of the list and work my way down,” says Rogers. “I never thought I’d get a yes on the first try.” The pair teamed up to create a new collection of sounds in two famous studios, A&M Studios in LA and Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, upstate New York.

With the Clearmountain sample CD in hand, EastWest booked a space at the September 1990 AES show in Los Angeles for the launch. Since 1948 the show, hosted twice a year – once in the US and once in Europe by the Audio Engineering Society – has been the globally pre-eminent showcase for audio and production tech, and Clearmountain was on the stand. “Bob was mobbed like a rock star, and we got a lot of free press.”

EastWest sold its complete stock at the show. Among those who visited Rogers at the show was Paul Jeffrey, who recorded with Doug at the first Harlequin studio as part of Schtüng and was central to the design and construction of the second studio. “Doug was in heaven,” he told AudioCulture in 2023.

The Clearmountain/Rogers collaboration ProSamples 1 / Drum Samples was followed by two more volumes in the next couple of years, including Percussion and Bass, as EastWest expanded its catalogue to other instruments. However, three decades on, that first collaboration remains one of the biggest-selling sample collections ever released anywhere, and it established the company as an industry leader.

American music engineer Bob Clearmountain's drum samples compilation, PRO Samples 1 / The Ultimate Drum Collection (1990), released through East*West.

EastWest’s catalogue continued to grow in the 1990s. The next year, they released the first collection to include MIDI-driven drum loops, and in 1995, the Ultimate Piano Collection took advantage of advances in sampling technology to offer multi-velocity piano samples (the keyboard will trigger different samples depending on how hard you hit the key), a world first.

Throughout this growth period, EastWest remained a hands-on business, with the Rogers-owned company doing pretty much everything from creation to the customer. As well as the virtual (software) instruments, and steadily advancing software technology, the discs (CD-ROMs), and the application of steadily advancing technology to that software, were manufactured and packaged in-house until downloading superseded that in the 21st century. The company also handled distribution and marketing.

One of the biggest breakthroughs in sampling technology came in the mid-1990s. Doug Rogers got a phone call from Jim Van Buskirk, a software engineer in Texas. Van Buskirk had developed technology that allowed the streaming of samples from hard drives without latency, ie, a delay. Before this, samples needed to be played directly from RAM (Random-Access Memory), as playing them from hard drives directly caused a small but noticeable time lag. The new technology allowed the computer to load enough of the sample into the memory of the computer to overcome that. It was revolutionary. Initially, Rogers was sceptical but Jim Van Buskirk was able to show that it worked. In 1997, Rogers partnered with Van Buskirk’s newly formed company Nemesys to create the GigaSampler software and instrument collections, which pioneered the use of “streaming from hard-drive technology.” It was a technical breakthrough without which the high-quality virtual instruments of today would not be possible.

Other partnerships were forged, especially as EastWest moved further away from just drum sample collections. A key one was with engineer and producer Ken Scott whose CV included producing David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and Hunky Dory albums, as well as records by Jeff Beck, Devo, Supertramp and Billy Cobham. He was also the recording engineer on all of The Beatles’ recordings from Magical Mystery Tour to The Beatles (aka The White Album) and the standalone singles recorded by the band in those years. As such, he knew Abbey Road Studios and the gear used in those years probably as well as or better than any other living sound engineer. Doug Rogers, ever the Beatles obsessive, was extremely keen to put together collections of Beatles sounds for EastWest. After 1990, the law on sampling copyrights was tightened substantially, so the only option was to recreate the sounds.

“Ken was involved in three Beatles albums and knew how to get [the sounds], so we teamed up. Much of the time was spent finding exactly the right equipment before we recorded a single sound because we wanted to get it right and be as close as possible to the original.

“I spent hundreds of thousands of dollars accumulating that gear: instruments, amplifiers, microphones and recording desks. It was like a treasure hunt trying to track it all down. EMI, in their wisdom, had dumped most of the tube stuff when the electronics changed to solid state. They thought no one would ever want to use it anymore, so sometimes there are only two or three of them left in the whole world. I bought a [Studer] J37 tape machine, a four-track used by The Beatles in Abbey Road, and I’ve kept it. I sold the mixers after the project ended, but I kept the tape machine because it’s unique sounding, and I use it for other work as well.”

In the late 1990s Rogers relocated to New York City for a couple of years, but apartment living was too tough on the family, so they moved back to LA and have been there ever since.

Public Enemy - Beats And Loops - Welcome To The Sampledome (2002) released on EastWest.

In 2002, EastWest released Welcome To The Sampledome, a two-CD collection created by Public Enemy for the company. It was the world’s first hip-hop sample collection by a well-known group.

A relationship with composer and producer Nick Phoenix, one of the pioneers of the birth of trailer music in the early 90s, began in 1994 when Phoenix approached EastWest to distribute a guitar and bass CD-ROM. It’s a relationship that quickly evolved into increasingly complex orchestral instruments, choirs, opera and virtual orchestras, all of which involved extensive live recording with often large numbers of musicians.

It was problematic. Both the cost and practicalities of these recordings meant that the producers, and particularly Rogers, were camping out in recording studios in Los Angeles for long periods, potentially limiting the scope of the growing number of projects, many aimed at Hollywood big-screen soundtracks; a Hollywood Orchestra collection alone has 800,000 samples.

I did it my way

Western Recorders, located at 6000 Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, is a big part of music history. Dating back to 1961 as a recording studio, the studio was created by Bill Putnam, himself a pioneering figure in audio recording credited with the concept and design of the modern recording desk and much of the ancillary equipment we now take for granted.

Doug Rogers' EastWest Studios, Los Angeles

In the 1960s, Western Recorders (renamed United Western Recorders in 1961) was partially owned by Frank Sinatra (until 1985), and its studios were responsible for The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and Smile albums, Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get it On, Sinatra’s 1960s catalogue including ‘My Way’, “That’s Life’ and ‘Somethin’ Stupid’, The Mamas & The Papas, Sam Cooke, Elvis, Ray Charles, Barbra Streisand, Blondie (‘The Tide is High’ and ‘Rapture’), U2 (Rattle & Hum), Michael Jackson (Thriller and Dangerous), Madonna (Like a Prayer), Whitney Houston (‘I Will Always Love You’) and Phil Spector (The Righteous Brothers), among countless others, plus many television and cinema themes including M*A*S*H and The Beverly Hillbillies. In the 80s, it was renamed Ocean Way and stayed that way until the Western Recorders part of the Ocean Way studio was sold, and the original Western Recorders building was rebranded as Cello in 1998. In more recent years, the studio’s credits include Blink-182, Rage Against the Machine, Rolling Stones, Tool, System of a Down, Weezer, Muse, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Alanis Morissette.

Changing times, however, saw a downturn in the business as many acts retreated into private studios using digital technology and the recording industry tightened their Napster-era belts. Cello declared bankruptcy at the start of 2005, and the studio was put on the market, with most bets on near-future demolition and redevelopment of what was an incredibly valuable piece of Hollywood dirt.

When it shut down, the studios were full of vintage gear. However, that was all behind padlocked doors. The city classed it as a historic site, but even with that protection, the decaying state of the buildings threatened its survival. On the hunt for a facility that would serve as both a recording studio for EastWest’s projects and a headquarters for the software company, Rogers looked at Cello but decided it was too much to take on, given the decay.

“I said thanks, but no thanks to the real estate person.”

Months later, it was still standing and for sale and Rogers was frustrated by the failure to find anything that sounded that good.

“It was like the last business on earth I wanted to get involved in again, but it became a necessity in the end because we were spending so much money on other studios. We just couldn’t afford to do that – we had to do something. We kept looking around, and that would just keep coming back and back and back, although it was so run down.

“We thought about it some more and thought maybe it is worth restoring because these rooms are so magical.”

On 17 January 2006, Rogers took the leap and acquired the studio, paying US $4.9m for the buildings and the land. Renovations didn’t begin immediately, hindered in part by the damage caused by a major storm before the EastWest acquisition, one that thankfully spared the actual studios. The plan was to somehow maintain the studio and to lift it stylishly into the future. It would not only be a home for the company but also a working, state-of-the-art 21st-century recording studio.

Rogers: “When I said to the people here, I don’t want to get some local studio designer to remodel the studios – they all look like hospitals to me – I want to get someone that’s got style, who can do something that musicians are going to appreciate. They just thought I was blowing smoke.”

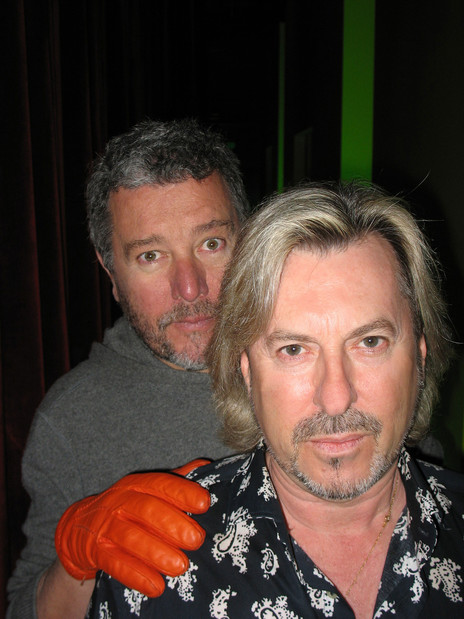

Doug Rogers and French industrial architect and designer Philippe Starck.

He decided upon Philippe Starck, the famous French designer.

“He was the obvious one. He had transformed hotels and nightclubs, all sorts of stuff. I contacted him, just rang his normal number and spoke to his people, but never heard a thing.

“Then, about a month later, the phone rang, and his secretary said, ‘Phillipe is interested in your project. Call him in five minutes.’ Of course, I called him – I was just over the moon. I called him, and it was as if he didn’t even remember what it was about. I had to remind him why I was calling him.”

It was Starck’s first and only music project, and it took almost three years to complete.

“He did an amazing job, and the musicians love it,” says Rogers. “They just love the atmosphere that he created. So, yeah, that kind of worked out. And as you know, I always try to do things a little differently. I knew it was going to be a money pit, and it was, but we did it.”

Doug Rogers' EastWest Studios, Studio 5

The studio, now renamed EastWest Studios, re-opened in March 2009, again into a depressed market, this time amid a global financial crash. The expenditure of the design, construction and substantive upgrading of the technical side cost EastWest at least a further $7m.

“We own the real estate, so that’ll pay off eventually because it’s right in the heart of Sunset Boulevard, in an area that’s undergoing major development. But we probably invested $12-13 million dollars into that place – try getting that back at, you know, recording rates, which are actually less than they were in the mid-80s! I just said to Candace, who’s the studio manager, ‘Look, I know it’s not going to make any money because this is the nature of the business, but just don’t lose any, you know, that’s all I’m asking.’ It’s a horrible, horrible business, but we justify it through the software company. We spend months in there recording this stuff and that’s how that’s how we get payback.”

Inside Doug Rogers' EastWest Studios

EastWest is one of the last of the so-called big studios in the USA, with four standalone studios in the complex. Music recorded there has had some 190 Grammy nominations in the 15 years since it reopened, more than any other studio in the world; this includes recordings by Kendrick Lamar, Frank Ocean, Justin Timberlake, and Beyonce.

Doug Rogers has received over 120 international industry awards, including Recording Engineer of the Year, and was named in The Art of Digital Music (2004) as one of the 56 Visionary Artists & Insiders.

It’s a very long way from a four-track in Mount Eden with a mud-filled carpark and driveway.

The EastWest Sounds software company, now in its 36th year, has also evolved. Currently run by Doug and his eldest son Blake, EastWest Sounds has over 42,000 virtual instruments in its catalogue. It has won or been awarded countless industry awards over the years with recording and software development both in Los Angeles and Germany.

However, in the age of Spotify and Netflix, the way we purchase and consume software was quickly changing. In 2015, Doug decided to move from the one-off purchase model to a subscription model, a shift which gave more subscribers access to EastWest’s complete collection of virtual instruments.

The circle completes ...

And so, the circle turns. The COVID-19 lockdown gave Doug Rogers a chance to reflect on his history and how he ended up where he did.

“The weird thing is it took a Kiwi to go to America and let them know what the future was going to be,” he says. “It’s the weirdest thing of all, but then that seems to be the way – it’s usually foreigners who have kind of paved the way in the States.

“We all come from a very hungry background. When you try to be in the music business in New Zealand, it’s like there was never any money and just about every day you are desperately trying to make ends meet. And so, you got to be good at what you do; you got to be on top of your game and just take advantage of all the opportunities that come along. And that’s not the mindset of the average American. So, you bring that with you. I got to the States, and I still had that hunger. Still do. And, you know, we just kind of annihilate everybody because they don’t work hard enough.”

Rogers’s current passion is lost New Zealand music, in particular, lost master tapes. Part of his reflection during lockdown revolved around the music he’d recorded at both Harlequin studios in the 13 years he was recording in New Zealand.

“I often talk to Morton [Wilson from Schtüng], and he said, “Don’t you ever have any kind of nostalgia with all this stuff you did in New Zealand?’ I said ‘sure’ and thought about doing something with the Harlequin recordings I liked. I started putting feelers out to track down the multi-tracks because I wanted to remix. I thought that would be a different twist, to remix these in my studio up here in LA.

“We decided to remix the second Schtüng album and look at releasing it. There were no tapes. Not even of the first album. We couldn’t find anything. We know that those tapes were given to Polygram, and then Polygram got absorbed into the Universal group; somewhere along the way, they all disappeared. I said to them, ‘You guys had these; what happened to them? Surely your record company does not throw out tapes.’ But they had no idea where they were.”

That was followed by a search for the tapes of one of the most successful New Zealand bands of the late 1980s, When The Cat’s Away.

Rogers had recorded and produced a single ‘Leader Of The Pack’ at Harlequin in 1987 followed by a live album, recorded at His Majesty’s Theatre. Both were released via CBS (later Sony) and were huge sellers. In the years since Sony had moved several times and, in the process, downsized substantially. Things were not kept.

“There was nothing anywhere,” he says.

The band was reforming and wanted to reissue their recordings digitally for the streaming services. Eventually, the album was lifted off vinyl at Stebbing Recording Studio. However, Rogers has tracked down the ‘When The Cat’s Away Live’ multi-tracks at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington. “Maybe I’ll do a re-mix just for fun when they complete the multi-track digital transfer,” he says. “The blend of those five vocals in When The Cat’s Away is just magical.”

It’s no secret that much of the music recorded in New Zealand in the 20th century is missing. Master tapes were dumped or destroyed, or have disappeared over the years as record companies merged or shut down. The multitrack and often the mixed-down production tape archives of most of the major label recordings are gone. The bulk of our reissues now come from pristine vinyl or even cassette.

“I buy things off Discogs because the masters are all gone. I’d love to be able to source the tapes – the masters that were sent to these mastering houses to actually cut the record would be great if there are no multi-tracks.” Both the Cat’s records had been mastered in Sydney at EMI’s 301, but they had nothing in their archives either, which probably meant the masters had been returned to New Zealand and lost or tossed out at some stage.

“When we shut down Harlequin and I was moving up to the States all the tapes that we had – we had a lot – were returned to either the artist or the record company, and they’ve all lost them,” says Rogers. “I’ve contacted almost all of them, and they’ve all lost them. None of them have any clue where they are. I would love to do a project where I remixed some of the ones that I really liked working on because, obviously, we have got a lot better.

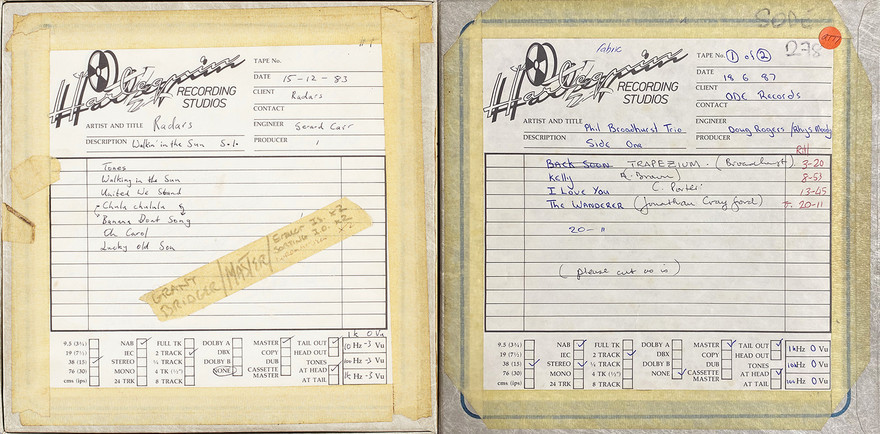

Master tapes from Harlequin Studios: The Radars and Phil Broadhurst Trio. Now lodged with the Alexander Turnbull Library.

“But also, just to save the tapes. [Dr] Michael Brown [Curator of Music at the Alexander Turnbull Library] is doing an amazing job, but there is only so much he can do, and it’s hard when things are gone. Where are they? Abbey Road has everything, you know. I have all the [Split Enz] True Colours demos, and I offered them to the record company. [They include] probably two hours of them jamming and actually putting together songs and creating those songs and the whole songwriting creation process. And I have all that; I have actually digitised it myself. The record company never asked for it back. No one cares.”

At the time of writing, I spoke to Rogers at his home in Mexico, from where he commutes to Los Angeles. I hadn’t spoken with Doug for almost four decades when I reached out to him by email. It’s fair to say our relationship had ended fractiously back then, despite all we’d managed to achieve and put on record in the early 1980s, from that 1977 Suburban Reptiles recording – the very first Harlequin record – to the double slam of The Screaming Meemees and Blam Blam Blam albums, a unique pairing of global standard albums that would not have been possible without Doug Rogers. I was also aware of what he’d achieved in the years since, and it was a story that needed telling.

After I reached out, we talked on Zoom for some six hours over two nights. We laughed and told stories, remembered. However, as much as I tried to keep the conversation focused on the task at hand – an AudioCulture profile that embraced 50-plus years in the business – it seemed to repeatedly return to the music and the minutiae of the Harlequin years, which went from a borrowed four-track in what was little more than a shed with egg cartons on the walls, to what was the most advanced “designed” recorded studio ever built in New Zealand, and the vast catalogue of New Zealand music it enabled.

The owner of one of the world’s greatest studios – one where Frank Sinatra recorded ‘My Way’ and Brian Wilson painstakingly constructed the music for ‘God Only Knows’ – is still the passionate kid who wrote to HMV asking for a job.

--