In 1982 Harlequin Studios' Doug Rogers was scheming. Never one to simply bank his accomplishments, and with Mushroom now gone from the studio, he launched his own record label, Ze Disc.

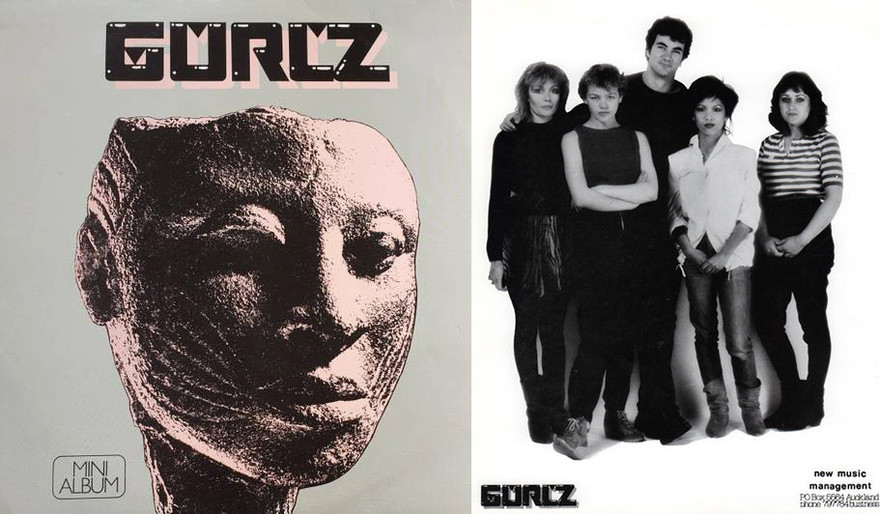

Initially distributed by RTC (later Virgin NZ), the first signing was The Gurlz, a five-piece with four women (including Kim Willoughby, soon to launch her solo career) and one male musician, Greig Blanchett: a still unusual line-up in New Zealand.

The Gurlz' EP on Harlequin's Ze Disc label, produced by Ian Morris and Paul Streekstra in 1982. From left: Carol Varney (drums), Kim Willoughby (vocals), Greig Blanchett (guitar), Debbie Chin (bass), Shelley Pratt (keyboards/vocals). - Roy Emerson

The Gurlz’ only release was the eponymous six-track mini-album released in November 1982, five months later than originally planned. Recording had been derailed by a van crash outside Whanganui on 31 May. The accident, which underlined the dangers of excessive touring and the often punishing road schedules many bands were subjecting themselves to in the 1980s, hospitalised Varney (and almost killed her husband Tim Mahon, of Blam Blam Blam) as they toured New Zealand supporting the Blams’ album. The Gurlz’ record was finally recorded in August and released with little fuss two months later. After recording an intended (but still unreleased) follow-up single with Ian Morris, they split in February 1983. Kim Willoughby, guitarist Greig Blanchett and Carol Varney re-emerged with Otis Mace in the short-lived and never recorded Heartstarters in June 1983.

The second signing to the label, which was now distributed by Wellington’s Jayrem, was another Auckland band, Tomorrow’s Partys. Their sole 12", ‘To The Beat’ – produced by Doug Rogers and Reid Snell – garnered a little Auckland airplay but otherwise disappeared.

Another Auckland band, Days Centrale were also announced as a Ze signing but never went beyond a track on the Propeller We’ll Do Our Best collection. They would return as Soul On Ice, recording two singles for WEA, and eventually formed the core of Fan Club.

Terror of Tinytown - I Am The Need (Ze Disc, 1983)

Arguably more exciting was the (ex-Spelling Mistakes’ drummer and songwriter) Julian Hanson led Terror of Tinytown. Their fine September 1983 single ‘I Am The Need’, produced by Rogers and Gerard Carr, may have spent just one week in the chart at No.48 but has since developed quite a sturdy reputation as a synth-pop collectable and classic.

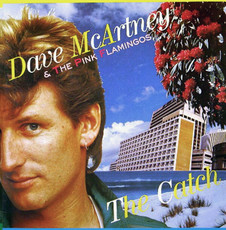

The final release on Ze Disc was the last album released under the Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos name. The Catch, produced by Doug Rogers and Davey Moore in December 1983, was financed and released on Ze Disc by CBS (who would release the Harlequin-related label releases hereafter as the relationship between Doug and CBS boss Murray Thom evolved).

Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos - The Catch (Ze Disc 1983, CBS Australia 1984)

The Catch started life as a Polydor release until that company, who slashed almost all local recording under a new boss, Australian Nigel Sandiford, declined to finance it anymore. Rogers re-recorded it for Ze, selling it onto CBS who paid Harlequin $25,000 for worldwide rights. Recorded over three months, it featured both McArtney and Harry Lyon, and while it wasn’t a sales success (despite strong belief from CBS), it was the final step before Hello Sailor inevitably reformed in April 1985. Hello Sailor would play a key role in the second half of the Harlequin story.

Spinnifex and the US

The first half of the 1980s was notoriously the era of the often grey deal, or testing how far the law could be stretched. As New Zealand emerged newly-deregulated from the constraints of the Muldoon era, now under the fiscal eye of Roger Douglas and the fourth Labour government, money was king. Along with the freewheeling stock markets and money dealers came the tax-reduction schemes, some walking a very fine line between legit and not. One of these was the leveraging using complicated tax rules which allowed investors in a creative project, called a Special Partnership, to write off more than they had invested against their tax. Investors, not all wealthy, and some just small investors guided by financial advisers, often successfully managed to make substantial profits from films funded under these leveraging schemes. It played a big part in the local boom in cinema in the early 1980s. Would it work for music? Harlequin and a group of partners thought it might.

Doug Rogers: “It was a smart idea. It was completely stolen from the film industry. I knew a guy who had done one of these deals for the film industry, and it occurred to me the tax break just mentioned the arts, not film. I went to him and said ‘Why couldn’t we do this with music?’ and he couldn’t see any reason why not. We needed investment to get music out of the country and this seemed to be a solution.”

Rogers and his business partner, Patty Greenall, had relocated to LA in mid-1984, where he worked under management contracts with both Kendun Recorders in Burbank and Artisan Studios in Hollywood, but they came back in early 1985 to set up the deal and partnership. Once back in New Zealand, he set up a new record label, Zulu Records, signing a worldwide distribution deal with CBS. Doug hired Hello Sailor’s Harry Lyon, who had been managing Harlequin while Doug was in Los Angeles, as Zulu’s label manager.

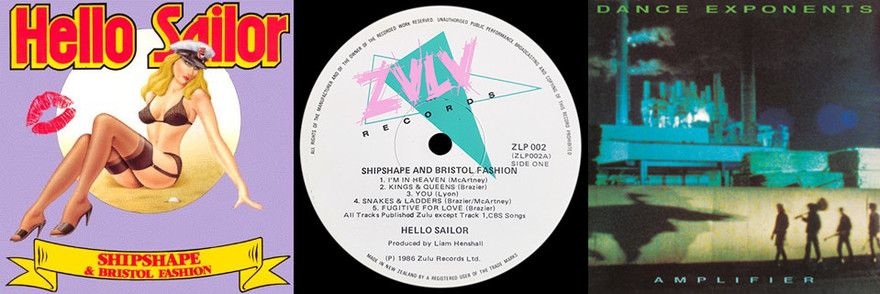

“We signed Hello Sailor and the Dance Exponents,” says Rogers, “who had been dropped by Mushroom and had no label. And (ex-Peddlers) Roy Phillips. I don’t know how Roy ended up in there.”

The idea was to use the money raised to record nine albums, three by each artist, recorded at Harlequin using offshore producers. These would then be mixed and mastered in the US for the international marketplace, and distributed by CBS (Columbia in the US).

Hello Sailor's Shipshape and Bristol Fashion and the Dance Exponents' Amplifier, released on the Zulu label in 1986.

The prospectus for the special partnership, now named Spinnifex Investments (with principals Geoff Leadley and Robert Rondel, an Auckland lawyer, and underwritten by Barclays Bank) said that the intent was to raise $2,230,000. Zulu would record the albums using funds advanced by Spinnifex and acquire the masters in these to repay those advances. The prospectus says on the front cover, “Investment in this venture is considered to be of a speculative nature.”

In the interim, as the partnership was being put together, Zulu recorded a reunion single with Hello Sailor, ‘Fugitive For Love’, produced by Rogers, which had gone Top 20 and spent eight weeks in the chart. What could go wrong?

It’s unclear how much was raised but it seems a substantial amount, as one album by each artist was recorded. Hello Sailor alone locked out Harlequin for three months starting in November 1985, with Liam Henshall and keyboard player Rob Fisher. Recommended by legendary British producer Muff Winwood, Henshall was the hot new producer behind UK band King’s big hit ‘Won’t You Hold My Hand Now’; Fisher was ex-Naked Eyes and went on to form pop duo Climie-Fisher.

Harry Lyon told AudioCulture in 2023, “You can hear the money on the tracks,” and you could. Fisher’s expertise was in the complex state-of-the-art Fairlight CMI digital workstation. It was a brand new machine, the first in New Zealand, owned by Alan Jansson and Garry "Gazz" Smith from formerly Wellington-based synth-electro band The Body Electric, who were now Auckland-based and working out of Harlequin. They’d purchased it with a loan after Doug Rogers had committed to use it for the Zulu projects.

Henshall was sent a tape of 40 Hello Sailor tracks, including songs previously recorded – Graham Brazier’s ‘Billy Bold’ and McArtney’s ‘Remember The Alamo’ included – but thought that since this record was for the international market the best songs, no matter the provenance, should be chosen.

Nobody really knows how much the album cost. But 40 years on, most people agree it probably wasn’t money well spent. Harry Lyon: “Some [tracks] used up to three reels of 24 track tape; the Maclay Duff [Distillery] Pipe Band were brought in to play on ‘Billy Bold’, Herbs came in for a session to sing ‘ummmm’ – once; Red McKelvie on pedal steel, a multi-tracked Annie Crummer and a harp all mustering feelings of paradise on ‘I’m in Heaven’; whips and rifle shots for ‘Remember the Alamo’ and of course plenty of Fairlight to give it that 80s sound ... then mixing at Electric Lady Studios in New York.”

The unfortunately named album, Shipshape & Bristol Fashion (“Graham used to refer to it as ‘Shit Faced and Piss All Passion’”) finally arrived in December 1986 and is not well remembered.

Doug Rogers: “Liam Henshall came in and made it sound like some other band, and it was like they just … It was a fucking awful album, and there was no saving it. I tried giving it to different people to mix it.” Henshall is now a professional photographer in the UK.

Two 45s were released – ‘Billy Bold’ in late 1986 and a 1987 Doug Rogers/Rhys Moody re-recording of ‘Winning Ticket’ which was an airplay hit. CBS declined to release it internationally.

The Dance Exponents album was arguably more successful artistically. Amplifier, released in November 1986, suffered from similar mid-80s excesses. But it also contained one of the band’s classics, ‘Caroline Skies’, released as the first single in August – plus re-recordings of ‘Sex & Agriculture’ and ‘Only I Could Die (And Love You Still)’, the second single, in November. Produced by Doug Rogers and US producer John Jansen – known for his work on the Jimi Hendrix catalogue, Television’s Adventure, the Cutting Crew’s ‘(I Just) Died In Your Arms’ and Lou Reed’s New Sensations – the guitar-heavy album was mixed at the House Of Music in New Jersey. Despite good reviews, only reached No. 18 in the local charts. Again, CBS International declined to release it.

The final release by The Dance Exponents on Zulu was the single ‘Brand New Doll’ in January 1987. While it garnered good reviews – Rip It Up said it was “their best thing for ages” – and was getting airplay, a member of the band, Brian Jones, was not happy.

Doug Rogers: “I co-produced the album with John Jansen, and we just knew that there wasn’t a hit single on that album. And so Jordan [Luck] came to me one day, and he said, I’ve written this song called ‘Brand New Doll’. He played it to me on guitar, and I said, that’s it, that’s the one, that’s the song – we need to record this. This album was actually released so we recorded it as a follow-up single and we glammed it up a bit. We tried to give it more of an international sound. Debbie Harwood sang backing vocals on it and it turned out sounding very international. CBS were over the moon – ‘this is something radio will play’. And then, the moment Brian Jones heard it, he said, ‘I fucking hate that record. Tell them to pull it.’ I had to make a call to Michael Glading (head of CBS NZ) and say ‘Michael, the band has told me to have the single pulled.’ He said, ‘You’re kidding me! This is the only fucking record that radio wants to play, and you want me to pull it?’

“I said, ‘It’s out of my hands …’”

It was also the last record The Dance Exponents would make. In April, they moved to the UK. When they returned to their 1990s success, they were simply The Exponents.

Roy Phillips, the UK born former leader of 1960s hitmakers The Peddlers, was less lucky. He recorded an album at Harlequin with American Mallory Earl, who had, in 1978, produced Split Enz’ Frenzy and the related hit single, ‘I See Red’. Despite an assurance in late 1986 that it was on its way, only one single was ever issued: ‘Step By Step’ in January 1987. It disappeared without trace and the album has never seen the light of day. Phillips was, and still remains, angry and disappointed but Doug Rogers claims there were no record company buyers for the finished album.

“He made an album but nobody wanted to release it. The album was okay. But they didn’t see any kind of future for him.”

With the lack of interest in the already recorded albums (in the case of Hello Sailor and Dance Exponents, both possibly accentuated by internal demons), Spinnifex and the Zulu label quickly faded away. Spinnifex Investments Ltd was removed from the company register in 1993. In the interim, the government had closed the tax loopholes in the legislation that empowered such special partnerships.

Harlequin’s last days

Harlequin had been busy while the trio of albums noted above were being recorded. The studio’s recording credits include the debut single for Ardijah, ‘Give Me Your Number’, Obscure Desire’s self-titled club hit, The Body Electric’s ‘Imagination’, Goblin Mix’s The Birth & Death Of Goblin Mix (delayed by a $5000 bill owed to the studio). There were also audio-engineering school classes in November 1986 and October 1987.

However, in 1987, the studio’s lease was terminated unexpectedly by the building’s owners. They had grand plans for a tower on the Albert Street, Victoria Street and Elliott Street block they owned. But the stock market crashed, and instead Auckland was gifted a 40-year empty eyesore.

The studio still had some years to run on its lease so they decided to fight it and asked the arts funding body, The Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council, for support. QEII’s music head, Brendan Smyth, testified on their behalf and the judge ruled in the studio’s favour, negating the termination. Stuck, the landlord was forced to buy out the lease for a substantial sum. Harlequin Studios, the recording studio that had done so much to transform New Zealand’s recording industry over the last decade, shut its doors early in 1988.

The Fan Club - Sensation (CBS, 1988).

Among its last projects were the debut album by the Fan Club, a group that had its roots in Days Centrale, and The Killjoys. Both had recorded in the early midnight-to-dawn recording sessions that made so much of the early indies explosion possible, with Days Centrale eventually signing to Ze Disc in 1983 (they recorded an unreleased album). Now with Malaysian-New Zealand vocalist Aishah fronting them under the Fan Club name, Doug Rogers decided to record the band and break it himself internationally. No more special partnerships. He signed them directly to CBS and, with Rhys Moody, recorded their 1988 album Sensation at Harlequin and, when that closed, at Mascot Studios in Eden Terrace, mixing the singles in Los Angeles at Can-Am Recorders.

Released in October 1988, the record took off around the world, especially in Southeast Asia where Malaysian audiences pushed the title track, plus ‘Paradise’ and ‘Call Me’, into the local charts. A second album followed, produced by Mark Berry, before they split.

By then, Doug Rogers had relocated to Los Angeles. His final New Zealand project was a brief partnership with Oceania’s Greg Peacocke and Paul Jeffery, and promoter Chris Cole. The quartet purchased Mt Eden’s Galaxy live venue from Phil Warren late in 1987 and, after extensive renovations, reopened it in May 1988 as The Powerstation. The partnership was short-lived and ended fractiously shortly afterwards with Rogers, Peacocke and Jeffery all walking away.

Harlequin Recording Studios Ltd was removed from the company register on 17 October 1990. However, by that time Rogers was established in the US with a new company. In the coming decades, it would revolutionise recording globally.

--