Shortly after Harlequin studio opened in February 1977, one of the first bands to record there was the Auckland trio After Hours. Neil Finn, Geoff Chunn and Buster Stiggs recorded five demos: ‘Late In Rome’, ‘Julia’, ‘Fallout With The Lads’, ‘Platform 3’ and ‘Ice Shakers’. They apparently exist in an archive.

After Hours in 1976 - Mark "Buster Stiggs" Hough and Neil Finn - Buster Stiggs collection

“That was the first time I ever heard of Neil Finn,” Harlequin’s Doug Rogers told AudioCulture, “and I was amazed at how talented he was. The songwriting was just amazing. And then, literally within a month or so of the sessions, he flew to the UK to join Split Enz, and that was the end of that band.”

There were recording sessions at Harlequin by Split Enz, who returned to New Zealand late in 1977 and then again in 1978, the second time without a worldwide record deal, having been dropped by their label Chrysalis outside of Australia and New Zealand. Even domestically, their relationship with Mushroom was increasingly tenuous. They needed a hit.

“I got to know the Split Enz guys during that time. Tim [Finn] and Phil [Judd] had fallen out for about the fifth time, and Neil, of course, had joined the band. They had returned from the UK, and they wanted to do some demos with us. They were on the brink – ‘if this record doesn’t happen, it’s all over’. They were broke and had a lot of debt. They’d lost everything. They lost their manager. Eventually, Neil Finn joining the band helped to catapult them into True Colours, which is still one of the biggest-selling New Zealand records of all time.

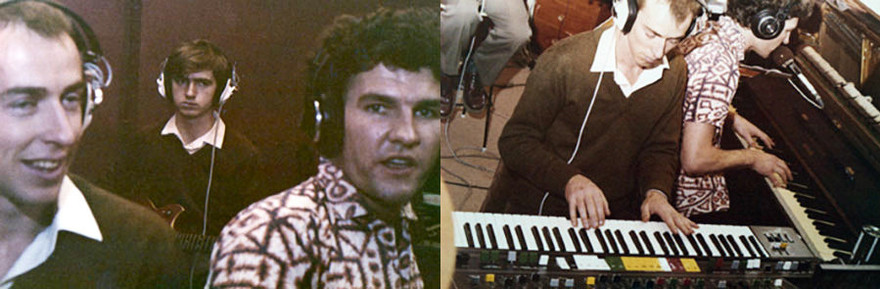

Doug Rogers with Tim and Neil Finn, Split Enz's True Colours demos, 1979.

“It’s very cool. I have 8-track tapes of those sessions; the demos, all the outtakes and all the rest of it,” says Rogers. “I’ve got hours of it. I guess Mushroom owns it, but there are hours of them jamming and actually putting together and creating those songs – the whole songwriting creation process. I have all that and eventually digitised it. Incredibly, nobody has ever asked for it back. No one at Mushroom or Warners [which now owns Mushroom] seems to care.”

Rogers says ‘I See Red’ was Enz’s answer to the whole punk movement. “They were trying to fit in. They were trying to navigate that whole thing where they didn’t come across as too theatrical and had a bit of a kind of a punkish edge. Peter [Terry] paid to bring them back for Nambassa 1979, and that’s when we started working on the early demos for True Colours, which was the next record. It was obvious to me that they had the songs to make a great album at that point, and I nearly got to produce it. We did all the demos and got on like a house on fire. We all really enjoyed it.

Split Enz: Eddie Rayner, Neil Finn and Tim Finn at Harlequin Studios, 1979.

“We had a great time. They couldn’t believe the sound I got out of that shitty little place, and so there was talk of me going to EMI in Wellington to produce the album there, then Michael Gudinski said no. He’d struck up a relationship with English producer David Tickle [who had also produced 'I See Red'] and wanted it recorded at Armstrong’s In Melbourne.

“It was absolutely the right move. It wouldn’t have sounded like the album that it ended up sounding like. He’d worked with Blondie and The Knack and gave Split Enz the sound that ended up selling all those copies. We could never have got that from EMI.”

As the months passed, the limitations of a single 4-track machine were an ongoing frustration. “We were recording on one 4-track and were always running out of tracks – having to put the drums and the bass on one track. We needed a solution.”

An aspiring and enthusiastic young West Auckland engineer, Simon Alexander, offered Doug the use of a second 4-track. This gave Harlequin the ability to bounce tracks across and go beyond that four-track barrier, much as bands such as The Beatles had done in the 1960s.

“I was introduced to Simon by a mutual friend. We linked the two 4-track machines together, and we could bounce one to the other and back again and basically build up multi-tracks that way.”

It was also the start of a lifelong friendship and a working relationship that continues. Simon (now Zennor) still works with Rogers when called on from his base, still in West Auckland.

As Harlequin’s equipment pool grew, so did the way it was used. A friend, Greg Peacocke, had returned from the US with state-of-the-art Cerwin Vega PA speakers, but he lacked a mixing desk for a forthcoming Hello Sailor tour, so he used the Harlequin mixer. After that tour, Greg Peacocke purchased his own desk and that was the beginning of Oceania Audio.

“It’s funny how these things began,” says Rogers, “with like-minded people cobbling together what they had because, as you know, no one had any money then, you had to find the resources where you could. Money was just not even a part of the equation. If you could pay the rent, you were doing really well.”

Nambassa

In 1976, organiser Peter Terry approached Rogers to work on the upcoming Nambassa Festival.

“I knew Peter through a friend from Wellington, Sue Miller, a fashion designer. I got to know him through her, and then, when he was planning to do his first festival, I think I was about the only person he knew who had any knowledge at all of the sound and music business, so he asked me to come onboard.”

Doug Rogers with Paul Moss with Barton's techs at Nambassa festival. Paul Moss collection.

Doug Rogers would go on to work on all the Nambassa festivals except the last. “It all started off very small in Waihi; at that time, it was a house-truck type festival. Very hippie, because the whole thing came at a really interesting time musically, a transition going on between bands that wanted to sound like Supertramp and the arrival of punk. All of a sudden all the bands that wanted to sound like Supertramp or Pink Floyd were out of vogue and Nambassa was on the cusp of that, it impacted the festival. That hippie lifestyle met the new wave, and it worked.

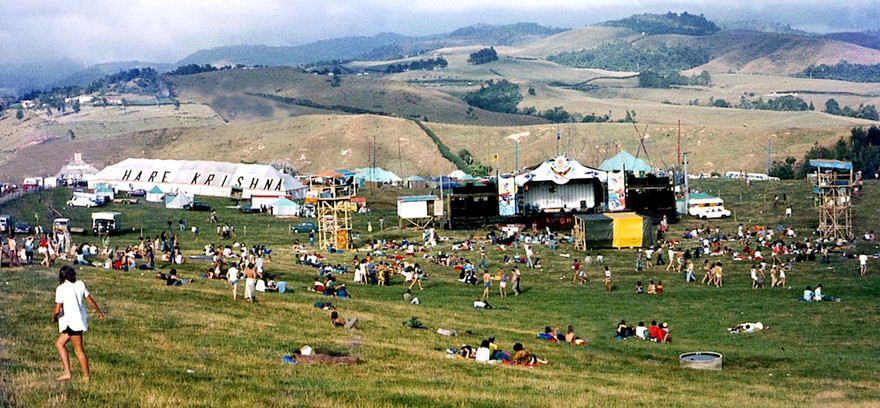

“Nambassa got bigger and bigger each year until 1979 when unexpectedly, some 75,000 people turned up. No one was expecting half that number, and it was madness. From an organisational point of view, everything was stretched to the max. They were bringing in supplies by helicopter. Peter had his team literally sitting on 44-gallon drums of cash. There were no credit cards in those days, just cash, so it was mindblowing. The music was phenomenal, and the crowds loved it, but I think that was the reason he decided not to do it in 1980. At a management level, it was just too much. It required so much energy to pull it off.”

Nambassa, 1979: to the left of the stage, the white Harlequin sound booth

In 1979, Peter Terry decided to record the event. He built Rogers a control room at the side of the stage into which Doug installed Harlequin’s desk and multi-track machine.

“It was the same gear we had in Harlequin but it just sounded so much better in there. The studio was so flimsily built and was up on eight or nine-foot high stilts. It was almost like having an open-air studio, whereas in the studio, the bass got trapped and got a little muddy.”

He later added the Mascot Studio 16-track to that and recorded the whole weekend. The audio was used for the Nambassa movie (now in Ngā Taonga) and for a double album issued by Stewart Macpherson’s Stetson label, both eventually released in July 1980. The album’s selling point was side four, with three songs from Split Enz, who, having been brought back to New Zealand by Peter Terry for the festival, turned in a fierce performance – despite having lost much of their gear in a rehearsal hall fire a few days earlier.

Oddly, when it was released, the recording credit was given incorrectly to Mascot’s Doug Jane.

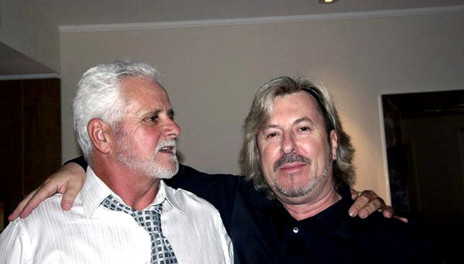

Lifelong friends: Nambassa's Peter Terry and Doug Rogers photographed in 2009.

Peter Terry and Doug Rogers have remained lifelong friends, talking periodically, but Rogers’s next festival experience was less positive.

Sweetwaters

“In late 1979, [promoter] Daniel Keighley asked me to do the sound and lighting and secure some of the performers for his Sweetwaters festival [on Auckland Anniversary weekend 1980], which I did.”

Rogers was credited as the Entertainment and Technical Production Coordinator for the Main Stage in the event marketing material. He was also quoted in the January 1980 Rip It Up very positively, saying that rig was the largest audio-visual-musical undertaking New Zealand had ever seen.

Forty-four years on, the event evokes a sour memory. “That was the last festival I did. It was a completely different festival altogether; it wasn’t about lifestyle anymore, it was primarily about music and money. It was more like a Western Springs show, out in the country. I only did the one because Daniel claimed they had lost money, and he never paid me. He told me that only 23,000 had been there. Later, the IRD did an aerial count and counted 45,000. He claimed then [that] many had got in free. Daniel was a very persuasive and charismatic person, but doing business with him was no fun. I was like down on my last legs financially, and he came in one day and said, ‘oh, the festival lost money’. They never paid me a cent.”

“In the 1990s, Peter and I talked about doing Nambassa again. I asked him if he’d be interested because it seemed like that kind of festival had kind of come around again, with what was happening in Byron Bay and others like that. We looked at it, and I researched it with [Oceania Audio’s] Greg Peacocke, but in the end, we just decided it was too risky.”

Schtüng

One of the starring acts at Nambassa was Wellington band Schtüng, whom Rogers had grown close to over the years.

Schtung on the Nambassa main stage in 1979. - Photo courtesy of Peter Terry and Nambassa Trust

“We came up [to Auckland] at the end of, I think, the summer of 76,” Schtüng’s keyboard player Paul Jeffery told AudioCulture in 2023. “It was the first Nambassa, and Doug was the person who got in touch. He knew us from Wellington and was dead keen to get Schtüng [for the festival]. He then introduced us to Greg [Peacocke], who had a couple of Cerwin Vega speakers he’d brought back from the States, and we used them on stage at Nambassa for side fill.”

Utilising those same speakers, Paul Jeffery and Greg Peacocke went on to co-found the sound company Oceania Audio in 1978, one of the major players in the industry in the years that followed.

Schtüng’s self-titled debut album was released in early December 1977. Despite critical acclaim, it had the misfortune to arrive just as homegrown punk also arrived, and their semi-classical prog rock sound seemed instantly anachronistic. Wanting to move forward, they asked Doug Rogers to produce their next album and managed to extract a budget from Phonogram, who, under label boss Stuart Rubin and A&R manager Gerry Beyering, were again proactive in the local scene.

Doug Rogers at the first Harlequin Studios with Schtüng.

The band recorded demos at Harlequin before heading south in June 1978 to the new Marmalade Studios in Wellington. It didn’t work out.

“I made a huge mistake, taking it down to Marmalade,” Doug Rogers recalls. “They’d just finished their 24-track studio, and the studio was a disaster. Nothing worked. It was just awful, and it essentially broke up the band in the end. The record company was pissed off. We did a few more tracks in Auckland, and then Morton [Wilson, the band’s guitarist] and I had a serious car accident. That was the end of the band.”

Almost. In late July, in one of the forgotten oddities of New Zealand’s musical past, came Thijs Van Leer. A Dutchman, Van Leer was a founding member of Amsterdam’s Focus, a band that had several big hits in the early 70s (notably ‘Hocus Pocus’, a US No.10 in 1973). The Music Trades Association, a grouping of music hardware retailers and wholesalers, hosted an annual show in Rotorua. “It was boring,” Paul Jeffery says, “and [Auckland company] Jansen announced that they were going to do a big one at the Town Hall with bands instead next time and somehow convinced the others. Schtüng were booked, and it was filled with gear Jansen had imported Lowry organs and expensive bits and pieces.”

Jansen constructed state-of-the-art gear for the show. “They were building the PA as the show was being set up, bringing amps down from the Jansen factory and plugging them in live ... that was hilarious.”

The show opened on 27 July 1978 with a concert by Van Leer, supported by both Hello Sailor and Schtüng (and a sound system, described by Rip It Up – possibly because of the experimental state of it – as “as grim as any turned on in the Town Hall this year”). Emboldened, Doug Rogers invited the Dutch flautist to Harlequin the next day to work with Schtüng.

Paul Jeffery: “Somehow [Doug] managed to talk Thijs into it, I mean, it was a bit of a scumhole. Van Leer came up to the studio the next day with his little manuscript book, and of course, I was the only one in the band who vaguely knew how to write and read music and he had all these ideas. He said, “What you need to do is try this and this and … ” and the rest of the band would be, ‘wha…?’ I was trying to call out chords to them but it didn’t connect. Nothing came of it.”

However, arguably, the invitation was indicative of how confidently Doug Rogers approached his business and what the future would hold. “Doug was such a mover and a shaker,” says Jeffery, “and we all thought he was pretty cool because of that, because he was dynamic and interested and encouraging. He did things. Made things happen.”

Hello Sailor

When Hello Sailor returned from their famed/notorious six months in Los Angeles in early 1979, they arrived with a bunch of demos produced by David Bowie’s guitarist, Earl Slick. Harry Lyon recalls: “The songs were part of our repertoire, and we wanted to be able to reproduce them live, especially the ‘I’m an ancient android’ line from one of Graham [Brazier]’s new songs ‘Olio’ that had an early digital harmonizer wound up to eleven to make him sound like a robot. To do that, Doug Rogers agreed to be our soundman for a national tour and essentially took his studio control room equipment from Harlequin on the road.”

Hello Sailor: Dave McArtney, Graham Brazier and Harry Lyon performing at Mainstreet, 1979 - Photo by Murray Cammick

Doug’s memory is possibly more nuanced. “I toured with them when they came back to New Zealand and did their live sound both in New Zealand and Australia, and, boy, that was an experience and a half: the New Zealand Rolling Stones. Can you imagine what the dressing rooms after the gigs were like? Oh, my God! You’ve got no idea, it was unbelievable.

“Graham had everything you needed to be an international rock star. Everything – great looking, great voice, great songwriter. Everything. But …

“I just felt so sorry for Graham. He just got bitten by the devil with his heroin addiction. Could never shake it.”

Paul Jeffery has yet another memory: “Doug brought the Harlequin recording console on the road. It was an absolute nightmare – they had to treat it with kid gloves because there was no road case or anything for it to protect it.”

Albert Street

Doug Rogers decided then that he needed something better than the studio in Mount Eden. “I’d seen first-hand what could go wrong when you build a studio like that and decided that I wouldn’t make the same mistakes if I did it myself.

“We had gone as far as we could [in Mt Eden]. The drive was an ongoing issue, and there was even a brothel upstairs, so in the morning, there were always these condoms outside the front door. I was looking for a place that didn’t have those kinds of problems. I had more fun there than any other time in New Zealand. We had no financial pressure. It was just a great time, but it was time to move on.”

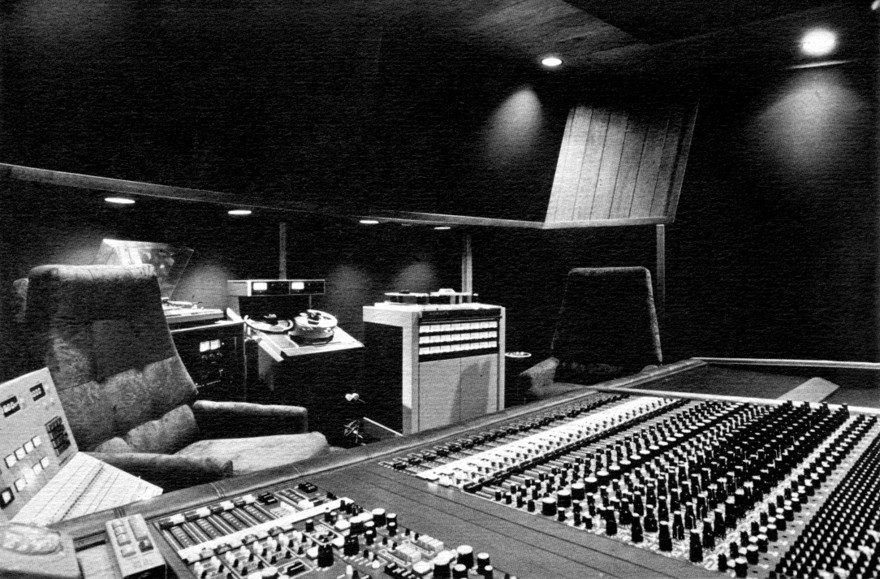

In September 1978, on a trip to the US, Rogers commissioned studio designers Jerry Smith and Jay Truax, who were one of the most successful studio design teams in the US, to design a new studio. He just needed a space, central and with easy access. He found one early in 1979, a multi-room site just off Albert Street in the city in the lane behind the (now demolished) Royal International Hotel. The lease was signed in February, and Jerry sent their construction foreman, Jeffery Nebb, to oversee the construction, assisted by Rowan Chadwick and Robbie Sinclair.

“It was actually, I think, a Hare Krishna temple,” says Rogers. “I liked it – right in the middle of the city. For some reason, those guys were moving somewhere, and the space became available, so I grabbed it. It took us about six months to build it, and I had to borrow a lot of money to get us up and running.”

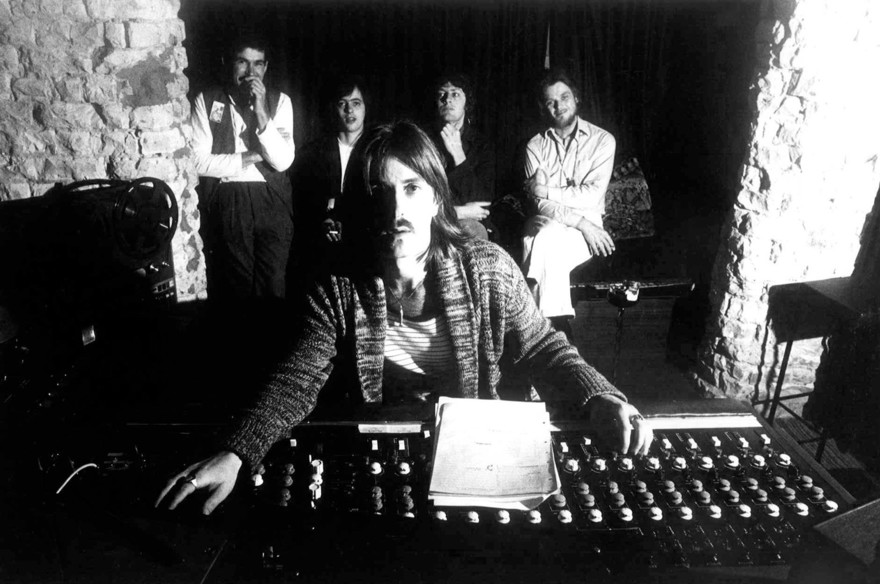

Doug Rogers in the new Harlequin on Albert Street, c. 1980

The quoted figure at the time was $500,000 and included a floating concrete floor, sitting on rubber to isolate the studio from the sounds of the city outside. There were rubber-mounted triple walls, suspended ceiling traps and a sound-insulated air conditioning system to prevent air-conditioning noise leakage. Twenty-four lines connected the studio to the Post Office data network to allow outside broadcasts to be recorded. It was, by any international standard at the time, absolutely state-of-the-art.

An ad for Harlequin's new studio, c. 1981.

The studio opened on 9 April 1980 for what was termed a six-month “break-in” period. Initially, the studio operated with an 8-track machine and a UK Soundcraft mixing console. By May 1980, with Simon Alexander assisting, the studio was offering bands a $25-an-hour deal at nights and weekends. It was eagerly snapped up by the dozens of new bands filling the city’s venues, not least the North Shore bands managed or guided by the young promoter Hillary Hunt, who booked the likes of The Screaming Meemees, The Ainsworths and The Killjoys in over the next few months.

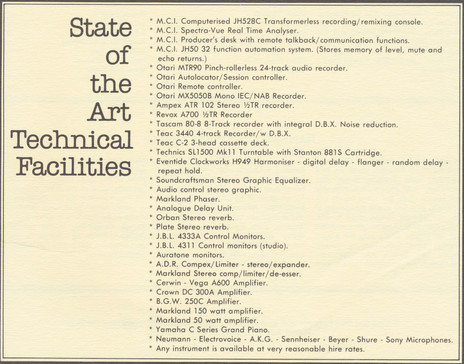

Harlequin Studio facilities, December 1980

Other bands who recorded in the new studio in 1980 included The Features (their second 12" EP), Techtones (demos of ‘Shed A Tear’ and ‘Hi-Flying’ followed by the Propeller single ‘That Girl’ backed with ‘The Silencer’ released in November, possibly the first release from the new studio), The Valentinos (featuring ex-Sheerlux vocalist Paul Robinson), Newmatics, The Respectables, Flight X7 and The Gordons (the classic and sonically challenging ‘Future Shock’ single recorded in one overnight cheap session in November). It was a fairly impressive list of what are now regarded as timeless New Zealand recordings.

At the Harlequin desk (L-R): Peter Solomon from Techtones, Paul Streekstra, Simon Alexander and Rhys Moody.

The bar had been notably lifted and Auckland now had several world-class studios, with Harlequin the clear industry leader. It was partially driven by a trio of new, young, inventive and fresh recording engineers Doug had brought on board: Steve Kennedy, Lee Connolly and ex-RNZ engineer Paul Streekstra. Later on, Rhys Moody, Reid Snell, Nick Morgan, Martin Williams and Gerard Carr joined the roster. A talented grouping of recording technicians, all would find their names on countless credits and be lauded in multiple awards in years to come.

The studio quickly became the nerve centre of a thriving young band recording scene, the likes of which Auckland hadn’t seen since the 1960s. The midnight-to-dawn rate – raised in 1981 to a still very affordable $30, then $35 per hour – meant the studio was heavily booked.

“That literally paid the bills, even though it was super cheap,” says Rogers. “It did two things: it paid the bills, and it enabled us to train up our new engineers – they used to start doing midnight to dawns and those would give them the opportunity to learn their craft in real-time.”

Nick Morgan, an engineer who would work in the studio both as an in-house engineer and later as a freelance, also got his start that way. “I started popping in, I guess, in wonderment in 1981 and sort of hung out,” he says. “I was kind of smitten by the bug of wanting to move from being a live engineer [with the Instigators] to a studio engineer.

“I worshipped Paul Streekstra’s work and thought he was the greatest engineer I’d ever heard. The kind of free and flowing style he had as an engineer was unique. I hung out with him as much as possible, watching and learning. I was the junior guy, rolling cables and doing whatever they wanted me to do. I picked up a lot from him, Steve Kennedy and Reid Snell – and Doug, of course. Then, soon, I started doing sessions on my own, when they deemed me worthy enough. It was all midnight to dawn, and soon I was running the whole midnight to dawn shift.”

Harlequin's control room in 1980.

At the start of 1981, the studio upgraded the 8-track main studio to an Otari 24-track MTR-90 recorder, later matched with an MCI computerised console, as used by the famed Criteria Studios in Florida (Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Rod Stewart and countless others). It was the first fully automated system in the country, matched with effects upgrades in a luxurious room designed to operate 24 hours a day. The 8-track was moved to a second studio in the building, opening in February. It was a huge investment – Rogers told Rip It Up in April 1981 that he’d spent $500,000 on equipment, design and acoustics – a huge risk, but his eye was on creating music he could sell to the world.

Nick Morgan: “I remember the day Doug and Patty [Greenall – Doug’s business partner] walked across the road with a bottle of champagne and gave it to the bank manager after MARAC [Finance] approved the huge loan. Doug would do things like that – he wasn’t ever afraid.”

Paul Jeffery – nicknamed The Professor by now – was a key part of the team that rebuilt the studio, an experience indicative of the passion that put it together. “I can’t actually remember being paid for anything I used to do at Harlequin, but I essentially lived there when we were installing it. The big MCI desk came in, and Doug got a guy out from America to commission it – a really strange guy who Doug fell out with terribly, as I recall.”

Doug Rogers, then, at considerable expense, flew in legendary US mastering engineer and Sierra Audio studio designer Kent Duncan to refine the room.

Paul Jeffery: “[After it was built] Kent Duncan came, and he and Doug sat in the control room one night for hours and hours and hours. I played the piano for them in the main studio and they kept getting me to do things, and they were fiddling around. I think they were trying to voice the studio monitors in there. He came back to do that commissioning of the room, if you like, where they decide on how the room’s working, and where they have to put a bit more absorption somewhere, or reflection somewhere else. He spent about a week or 10 days there with Doug and the engineers, just fine-tuning.”

Class of 81

1981 was an important year for Harlequin, and the work coming out of the Auckland studio was industry-transformative. In March 1981, the Class of 81 album was released on Propeller, and 11 of the 12 tracks came from the midnight to dawn deals (the 12th, by The Newtones, was recorded in Christchurch at Nightshift Studios); it topped the compilation charts. The same month, Blam Blam Blam’s eponymous 12” EP was Top 20, and they followed that with two more Top 20 singles that year, ‘There Is No Depression In New Zealand’ (July) and ‘Don’t Fight It Marsha’ (December).

Class of 81 (Propeller, 1981)

A double A-sided 45 on Bryan Staff’s Ripper label, from The Screaming Meemees (‘Can’t Take It’) and the Newmatics (‘Judas’) was also released in March and spent three weeks in the Top 40. After signing to Propeller, both bands found more success later in the year, with the Newmatics’ double 45 Broadcast OR (co-produced by Don McGlashan) reaching No.13 in October.

It was The Screaming Meemees single ‘See Me Go’, released in August, that helped define Harlequin’s year when the single became the first New Zealand record – 45 or LP – to enter the charts at No.1. The song had become something of a cause celebre in the studio with at least three versions being recorded there, with multiple credits from Doug Rogers, Paul Streekstra, Pop Mechanix’ Andrew Snoid, Ian Morris and myself appearing on various recordings. The Meemees’ sequel, ‘Sunday Boys’, was another Top 10 single in December, produced by Ian Morris with Steve Kennedy on the desk.

If the singles by the “Screaming Blam-matics” in part defined Harlequin in 1981, then so did two albums, albeit from opposite sides of the musical divide. The Gordons’ self-titled album was a sonic tour-de-force, recorded in 22 hours in October with Simon Alexander engineering and co-producing. Released in December, it failed to chart. But given its audience, perhaps more importantly, it was named the best album of 1981 in Rip It Up’s annual readers’ poll. The album received the inaugural IMNZ Classic NZ Record award in 2013 and was, with a global reputation, reissued worldwide in 2021.

Graham Brazier’s debut album could not have been more different. Funded by his manager Chris Cole with a $4000 budget, the Paul Streekstra-engineered Inside Out was put down over evenings in August and September with friends and Rogers contributing to it. Brazier was in periodic detention for assorted offences which didn’t help and when the album was licensed to Polydor for November release, a disinterested record company did little to sell it. Despite that, an album that contained ‘Billy Bold’, ‘No Mystery’ and ‘High Wind In Jamaica’ among its many highlights could only grow in stature over the years and, like The Gordons, is now regarded as one of our greatest long-players, with both albums rating highly in the May 2023 AudioCulture Classic NZ Album poll.

1981 also saw album releases from Graeme Gash (ex-Waves), the gorgeous After The Carnival, engineered by Paul Streekstra and co-produced by Graeme Gash and Lee Connolly; and West Auckland Stooges-obsessed punks The Dum Dum Boys, whose Steve Kennedy-produced Let There Be Noise would become one of New Zealand’s most collectable records in years to come.

Both The Screaming Meemees and Blam Blam Blam would commence albums in late 1981, the Meemees working with Steve Kennedy and Ian Morris, and the Blams with Paul Streekstra.

The other significant record was a 45 by Dave Dobbyn’s brand new band, DD Smash. Dobbyn, who had worked almost exclusively at Stebbings until now, released his second single with the band, the Ian Morris-produced, Doug Rogers and Paul Streekstra-engineered ‘Repetition’ in late December. The single peaked outside the Top 20 at No.25.

--