It’s the mid-2000s and Doug Rogers is commuting daily to work in Los Angeles. The daily commute took him past the site of the iconic Western Recorders studio at 6000 Sunset Boulevard, where everyone from Frank Sinatra to the Beach Boys to The Rolling Stones to Madonna – the list is endless – recorded over the previous four decades.

Doug Rogers on the cover of MIX magazine, October 2014 issue.

At the end of 2004, the studio went bust. It had been renamed several times and was in a semi-derelict state after some years of neglect.

In early 2005, Doug Rogers, originally from Whanganui, was on the lookout for a recording studio in the city that could suit two purposes. It needed to double as headquarters for his software company, as well as a place to record the samples and increasingly complex software instruments he was creating. He took a look at Western, which was now for sale, but decided that the rundown state of the facility meant it wasn’t something he needed in his life. Months later, he was still on the hunt and hadn’t found anything with spaces that sounded as good as Western, so he revisited the idea.

In the 1970s and 1980s, in New Zealand, Rogers had, not once, but several times, taken jumps that revolutionised local recording. Here he was, decades on, about to take a similar leap. He would take the software business into the facility and rebuild the whole complex as a state-of-the-art studio for other clients. He took the plunge, paying US$4.9m for the land and the buildings and then started the renovation process, a process that would more than double the purchase price.

It was almost four decades since Rogers, a Beatles-obsessed schoolboy, started his career writing an amateur music column for his local paper as an escape in a small city he desperately wanted out of.

Dear HMV …

Growing up in a sleepy North Island town in the 1960s had its disadvantages, especially if you were a Beatles-obsessed teen who wanted to be in the music business. Few towns were further away from the music industry in that decade than Whanganui, and Doug Rogers exactly fitted that description.

“I was a Beatles maniac … they were God to me, and I just wanted to be in the music business somehow, but there was no music business in Whanganui, he says. “I don’t even think there was a recording studio anywhere – the local radio station was the only place where you could record anything.”

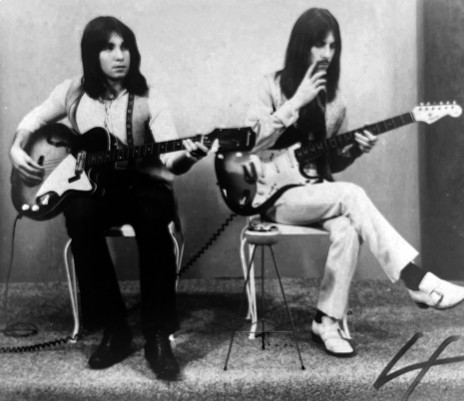

Ray Battersby (left) and Doug Rogers

His interim solution was to convince the local newspaper, the Wanganui Chronicle, to publish a regular music column. In partnership with his best mate Ray Battersby, Rogers created ‘The Young Set’ which combined news with reviews.

Rogers says it got him into all sorts of trouble at school. “The school was dead against anything to do with rock music,” he says, “and I was sort of like the devil in disguise because I wrote a column in the local paper, so they gave me a hard time.

“I began writing to the record companies and they started sending us records. We developed relationships with the record companies and any time a local tour would come through, they would send us to interview the bands. They would also send us records to review and when we’d go to Wellington, they’d just load us up with more records in the hope that we would review them.”

It was a means to an end for the schoolboys, then in their last year at Whanganui High, a key part of their exit plan from Whanganui into the industry they wanted so badly to be part of.

The day they both finished high school forever, the pair jumped onto a bus and headed to Wellington, never to return. It was the end of 1968.

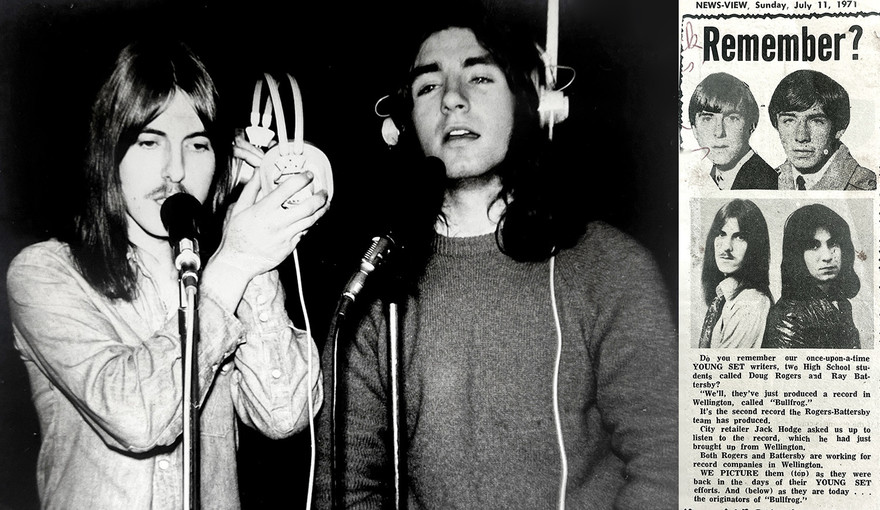

Doug Rogers and Ray Battersby

“I had some contacts in the record companies, so I wrote to them all asking for a job,” says Rogers. “I tried to get into HMV – it was my preferred place to end up – but they had nothing. Then I got a response from Murdoch Riley at Viking offering me a job. He was a terrific guy and gave me a job which paid $28 a week. I was working with his artists – he seemed to attract some of the most interesting acts at the time – as an assistant.”

Ray Battersby, however, had scored a position at HMV in Wakefield Street, where the multinational had what was then New Zealand’s state-of-the-art recording facility. As part of his new job at Viking, Rogers found himself spending a lot of time at HMV.

“Viking had no studio in Wellington, so they used to record in Wakefield Street. I’d always had at the back of my mind that I wanted to go there because they had a recording studio and Viking didn’t. Eventually, Ray got me a job there – I wasn’t doing recording at that time, but I was around a lot of recording and knew that was what I wanted to do.”

Now employed by HMV, Doug Rogers began to watch and learn. The HMV pop machine was in full swing at the time, with a talented production team led by Peter Dawkins creating hit after hit, and radio nationwide supported the local industry even if the playing field was somewhat stacked in their favour.

“I wanted to go to HMV because they had a recording studio and Viking didn’t.”

“Peter Dawkins and Alan Galbraith were truly great producers but cleverly HMV and the other record companies would also take hits from overseas and give them to local acts. They would hold up the release of the overseas original to allow the local artist to have the hit.

“It was like the New Zealand Wrecking Crew. They had a bunch of very accomplished local musicians, and they would just bang out these hits, and then they’d find some pretty face with a good voice to stick out front, and turn them into stars like Mr. Lee Grant, Craig Scott or Shane. Dawkins did an incredible production job with records like Shane’s ‘Saint Paul’ so the system worked. These producers were talented, and they didn’t have much to work with technically. I think about the equipment that they had to work with, and some of the stuff that they managed to produce is remarkable.

“Eventually the parent companies found out but until then it helped create one of the most successful periods of New Zealand pop ever. The public was genuinely engaged in New Zealand music at that time, and so was radio because they had all these hit singles that they could play by local artists. Once the overseas labels got wind of what was happening, they just killed it. And then all the bands and artists who had been doing covers had to start writing their own stuff, and radio lost interest with a few exceptions each year.”

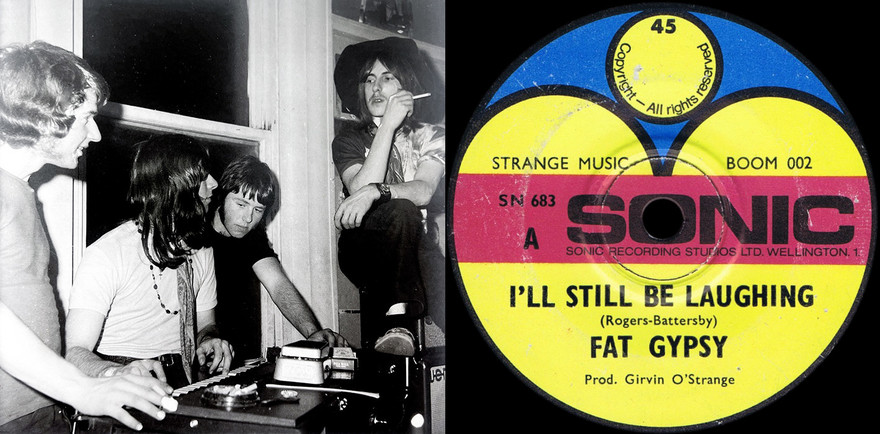

Doug Rogers and Ray Battersby in Fat Gypsy, and at right, their 1970s release I'll Still Be Laughing (Sonic, 1970, produced by Girvan O'Strange).

While working for Viking and HMV, the two friends from Whanganui also jumped onto the other side of the industry, recording and releasing two singles for the tiny Sonic label. The first, under the name Fat Gypsy, was a rocky 45 called ‘I’ll Still Be Laughing’ in 1970, and the second – ‘Bullfrog’, in 1971, as Rogers-Battersby Legend – was a more poppy affair. However, both singles disappeared without bothering radio or the charts. More successful was ‘Here In My Heart’, composed by Rogers and Battersby, which graced the flipside of Creation’s smash hit ‘Carolina’, winner of 1972’s Loxene Golden Disc.

Ray Battersby would later be seen in Wellington new wave band The Puppettz, who recorded two singles for Bunk Records in the early 1980s, and then again in the 1990s in Bizarre Tales.

After three years in Wakefield Street, Rogers did what many young New Zealanders did – and still do – and moved to the UK, arriving there on 16 March 1973, the same day Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon was released. There he honed his studio craft, working in the sound business and staying for a year.

Back in New Zealand, EMI (formerly HMV) had made a disastrous mistake. They’d decided to move their established recording studio out of the Wakefield Street address it had occupied for over a decade, close to the lucrative advertising industry and the entertainment hub, and move it to a new facility in Lower Hutt. Advertisers saw it as too far to travel, so new studios in the central city, notably Marmalade, began to eat into EMI’s work.

“We all said, ‘Who’s going to go out there? Who’s going out to Lower Hutt to record? It doesn’t matter what you’ve got out there, no one’s going to go out there and make records. It just doesn’t have the vibe.’ Sure enough, that studio was a complete turkey. All the great producers left and they ended up just selling it for parts in the end.”

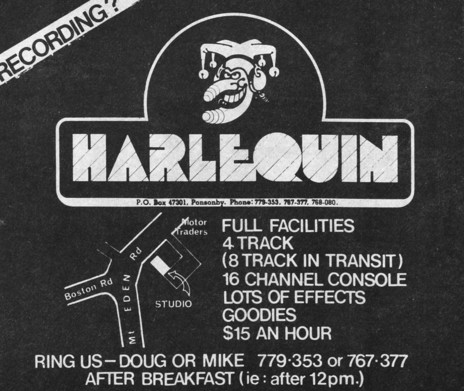

Rip It Up, November 1977: an ad for Harlequin Studios shows a map of the first premises, on Mt Eden Rd.

Rogers instead made a pragmatic decision to move to Auckland in 1975, and to create his own recording studio with his business partner Patty Greenall. The relocation made sense: in the mid-1970s, the record industry had begun its inevitable move north; WEA, the soon-to-be-independent CBS, most of Polygram, RTC, Festival and Pye/RCA were now based in the biggest music market in the country. EMI would not follow for another decade, and their once-dominant studio was increasingly out of the running.

Rogers had to start at ground zero. “I decided to try and cobble together the equipment to start a studio,” he says. “I knew Alastair Riddell very well from EMI. Alastair had just had a huge hit with ‘Out In The Street’ and was on top of the world. He also had keyboard player Eddie Rayner in his band at the time. I got to know all those guys. Alastair had a 4-track TEAC 3340 and I had a [recording] desk that I had constructed for a PA system that never happened, built by Moby [Michael Diack], an electronics wizard.”

Rogers had the basic equipment in hand but needed a space. Riddell came to the rescue again. “Alastair said, ‘I know this guy who has an electrical repair shop in Mount Eden. He’s got an empty studio space under his shop.’”

Preston Bruin, Simon Alexander, and Jed Town (The Anaesthetics) relaxing outside the first Harlequin studio premises at 81 Mt Eden Road, Auckland. In the background is Geoff Martin.

The space, under 81 Mt Eden Road, had been fitted out for use as a studio a decade or more before but had never been used as intended, sitting empty and unloved ever since. Access to the space was down a very steep drive to the side of the repair shop.

“Alastair told me it was just sitting there, basically ready to go. We went and looked at it and thought, ‘Perfect, this is it. We don’t have to spend anything …’”

The place had a bar in the control room, reflecting the owner’s idea of a studio. “We bought egg cartons and put them on the walls to try and deaden it a bit, then we covered them with drapes, so you couldn’t see them. But, yeah, it worked well. Some of the stuff I recorded in that studio still holds up today.

“Some of it is sounding a bit old now, partially because the transfers were never done properly, and – of course – the ubiquitous cassette was around in those days and those things were just a disaster, they would never translate from one machine to another. If you recorded on one machine and you played it back on the same machine it was semi-okay, but if you tried to play it back on another machine it was just always off.”

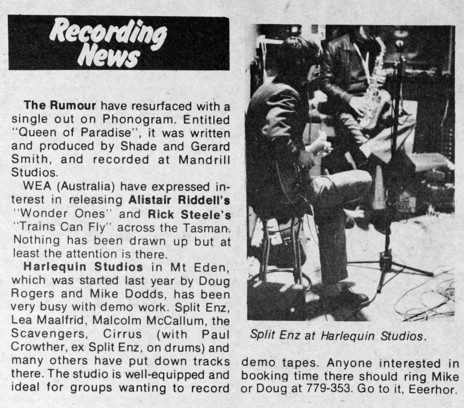

Rip It Up, September 1977: Split Enz records demos at the first Harlequin studio on Mt Eden Road.

Harlequin Recording Studios opened in February 1977 and quickly became popular with bands and musicians wanting a quality product from an experienced engineer that wouldn’t break the bank. Many clients were part of a maturing Auckland live music scene that would explode over the next few years as punk and post-punk arrived. Marketed as “The Biggest Little Studio In The World”, early customers included Lea Maalfrid, Paul Crowther’s post-Split Enz band Cirrus and Malcolm McCallum.

“It was super cheap and so we were attracting all the up-and-coming bands. I had a lot of fun during that period. We were there for two or three years [it closed early in 1980], and we just bartered much of it. I did stuff for Alastair for free, and he lent me his recorder as payment.”

However, it was also testing. The steep drive also acted as a drain of sorts, and when it rained (as it often does in Auckland) the water flowed down to the gravel carpark at the bottom, quickly transforming it into a muddy swamp. Access to the studio tested everyone, especially musicians or road crew trying to load gear into the studio via the slippery and unforgiving uphill pathway that led to the studio door.

Robert Gillies, Mal Green, Nigel Griggs at Harlequin Studio in Mt Eden Road, September 1977. - Photo by Murray Cammick

Vehicle access was another issue: “To get up the hill, you had to take a run at it, and it would often be the second or third try before you got the momentum up to make it.”

(One night, after an all-night Suburban Reptiles session, we came out to find that I’d left the lights on in the red Mini that sufficed as the band’s command vehicle, and the battery was completely dead. It took an already exhausted five of us to slowly push the car backwards far enough up the steep hill to allow me to jump in, then roll it forward back down the hill, gathering enough momentum to jump start it. We repeated this a grinding three times before I finally managed to successfully kick it back to life. I then had to try and get sufficient speed up to allow me to escape up the hill and park it, ready to receive the Reptiles drum kit – yes, we carried it in a Mini – which then had to be carried up piece by piece.)

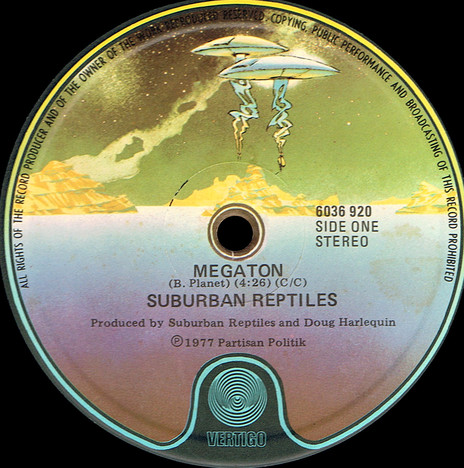

Megaton / Suburban Reptiles 12" (1978) with the first Doug Rogers credit, recorded at Harlequin

Harlequin was the venue of at least three sessions from the Suburban Reptiles in September and October 1977. These sessions, a learning curve for us all, eventually produced the ‘Megaton’ single, which was the first released record (on February 22, 1978) recorded at Harlequin. Nominally produced by Tim Finn, who had temporarily returned from the UK with Split Enz, the credit more correctly went to Doug Rogers, who guided a quintet of studio novices through the creation of their debut single. The credit I added to the record was “Produced by Doug Harlequin” – I didn’t know his last name when I filled in the label copy – and, although it was far from his first production, was the first printed production credit for the new studio owner to appear on a released record.

Fellow Auckland punksters The Scavengers had earlier recorded at the studio; when they put down six or seven songs early in 1977 they were probably one of the first bands to do so outside of Doug’s immediate musical circles. Guitarist Johnny Volume told AudioCulture, “[It had] sound-deflecting beach umbrellas on the ceiling ... Des had been visiting pubs and clubs to ask if they’d let us play. They all wanted to know what we sounded like, so we pooled our money and went to the Harlequin, as it was local and the cheapest studio around … it did the trick.”

The band returned again in late September to record two tracks for TVNZ’s Ready to Roll, a cover of the Sex Pistols’ ‘Pretty Vacant’ and an original, ‘I Don’t Like You’, both of which have been lost over the years.

In May 1978, Th’ Dudes recorded two demos – it was the first time Dave Dobbyn recorded in a studio – and an intriguing trio comprising Phil Judd, Brent Eccles and Mike Chunn was noted in Rip It Up as recording there in June. A month later, Fane Flaws booked Spats into the studio where the band that would later morph into The Crocodiles recorded their classic ‘New Wave Goodbye’.

In November of that year, the studio recorded Dunedin punk band The Enemy’s full live set with departing bassist Mick Dawson. Of obvious historical importance, this has still not had a full release but exists in the Chris Knox archives (not at the Alexander Turnbull Library) and has been bootlegged in part over the years, in inferior quality, off cassette. Auckland new wave band Sheerlux also recorded two demos the same month.

After The Enemy morphed into Toy Love in January 1979, the band recorded tracks that could be the three tracks found on AK79 (there is some argument that these are later Mascot recordings).

Art punkers The Plague entered Harlequin in May 1979 (although their tracks were not released until 2015, digitally, and 2022 on vinyl), and The Swingers put down ‘Certain Sounds’, ‘The Way We Used To’ and ‘The Jinx’, none of which have ever been released. What were released were two tracks by The Primmers in April, ‘Funny Story’ and ‘You’re Gonna Get Done’, both of which found a place on AK79.

From Scratch also recorded in Harlequin, with Phil Dadson bringing in his experimental percussion group several times in 1977 and 1978. Rogers recalls, “They had all these big long plastic tubes, and I was like, ‘How the fuck am I going to record these? It was a challenge and eventually, we figured out that you attached a mic to one end outside of the sound hole. We did it.”

The Terrorways were possibly the last band to record at the original Harlequin when they laid down ‘She’s A Mod’ and ‘Never Been to Borstal’ in November 1979, also for AK79.

--