There are a million stories in Christchurch City and Jim Wilson’s contribution to their music scene is one of them. By his mid-teens he was running and promoting teenage dances and later booked and promoted a plethora of bands into Christchurch venues such as The Gladstone, the Hillsborough, and the Star & Garter. He created a musical hub that was crucial to that city’s musical growth. Jim is the sort of guy who just wants to light up the sky with what he does.

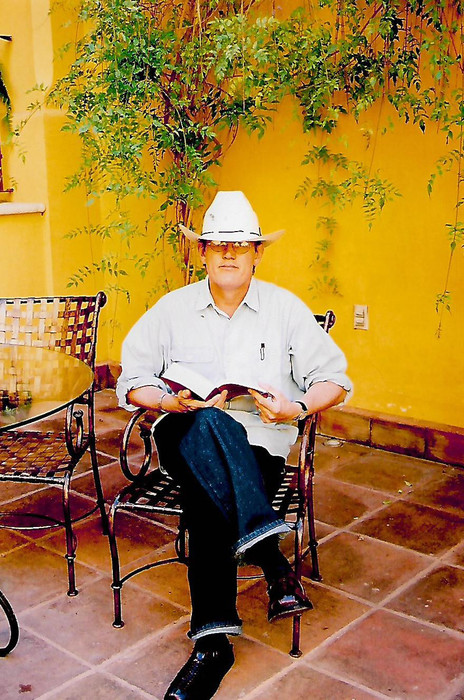

Jim Wilson in the US. - Jim Wilson collection

These days, Jim is better known as the founder and owner of Phantom Billstickers, a nationwide poster and promotional company that has a huge and diverse client list. Jim has always seen the poster as “flora for the concrete jungle” and putting colour in the streets.

Jim grew up in Russell Street in Dunedin during the 1950s, the youngest child. His older brother Colin was 14 years older and “a really nice guy, a rugby player who worked with heavy earth-moving machinery at Benmore but also had a touch of the Devil in him”. Colin loved Jerry Lee Lewis. Jim’s sisters loved The Beatles. One of them ran down the street after The Beatles when they played in Dunedin in late June 1964; at the time Jim was barely 13.

His childhood memories still resonate strongly. In an email to me in 2015, he wrote: “I well remember being in the kitchen in my parents’ house in Dunedin sometime in the mid-60s, or maybe it was in Christchurch. What I do clearly remember was the old valve radio beaming the Spencer Davis Group into the room. I remember the feeling of becoming so alive in tune to the music.

“Like many other kids born in the 50s, music and sport, was an important factor in developing one’s identity. It was both crucial and cultural!”

Before The Beatles’ 1964 New Zealand tour, the first wave of New Zealand rock’n’roll artists – Johnny Devlin, Max Merritt, Ray Columbus, et al – paved a path for bands that were later seen nationwide on black and white TV screens on shows like C’mon.

Bands such as The Underdogs and The La De Da’s were part of the wave that especially excited Jim’s musical curiosity. “I have no doubt that a lot of these guys gave true life to many Kiwis (myself included), at a time when society was strangling us in strange and unusual ways,"” says Jim “They set us on a path. We were so lucky.”

The Beatles provoked a reaction among young New Zealanders who embraced the beginnings of a youth culture that head butted with this country’s “puritan patriarchy”. As Christchurch-born poet and playwright Alan Brunton once wrote, “People stood for something else, their clothes and hair had symbolic roles, people played roles their accoutrements demanded.” (read AudioCulture, “Hey Bird”, part two)

Jim Wilson's father, Sid Wilson. - Jim Wilson collection

Jim’s parents relocated to Christchurch in the mid-60s. “I came out of high school like a bullet in 1968,” he wrote in his blog, A Tinker’s Cuss. “My father had announced that I could not go back to school to sit university entrance exams and that I had to get a job. My older brother [Colin] had died a year or two earlier and this left my family deeply sad and explosive on the inside. Of course, none of us said anything. I merely saw my dad hang his head in misery every single day and I know that my mother cried herself to sleep. Good mothers will do that. I never knew my dad and I really would have preferred to have seen him explode and then to have started to speak and to open up. I can now only speculate as to what he thought.”

In Christchurch, Jim’s early work experience included stints working in petrol stations and railway yards. Inevitably, he gravitated towards music. The music business at that time was still a fledgling industry, but a camaraderie and excitement was palpable.

“When we moved to Christchurch, I met one of my very best mates and a joker who was a brother to me his whole life through. His name was Mike Jones and his mum owned a dairy down by the railway tracks on Wilson’s Road. Our family lived just across the street. My mum worked in Melhuish’s pickle factory that was almost next door to our house and my dad worked at Stainless Castings in Woolston. This was good work for both of them and they enjoyed it. It took me a while to get used to a Christchurch summer after a Dunedin one, but I enjoyed the change. Christchurch just seemed to have more fresh air. I have always cherished having good mates. There is nothing better for me than the feeling of being part of a team.” (A Tinker’s Cuss, 2015).

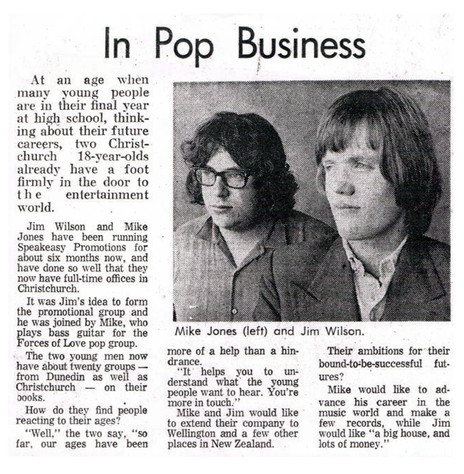

Jim Wilson and Mike Jones of Speakeasy Promotions, 1969. - Jim Wilson collection

Between 1968 and 1972 there were regular dances in halls all over town: Brake Street in Upper Riccarton, Zone 2 on Selwyn Street, Surf City in South Brighton, a hall down Linwood Avenue, one on Tennyson Street, the Mt Pleasant Community Centre Hall, the Caledonian Hall, the Horticultural Hall. Typically, these dances – held either on a Friday or Saturday night – would draw 400-800 teenagers.

Jim: “It was outrageous fun to be out and to be laughing about whatever beset us. Our childhoods had cooped us up and we were about ready to be let out.”

Jim Wilson and Mike Jones, 1969. - Jim Wilson collection

Mike and Jim, aged about 17, would hire venues like the Mt. Pleasant Community Centre Hall and book, promote and run teenage dances. Sometimes these gigs were fraught with friction where the kids were at one end of the hall while the Epitaph Riders bike gang took over the other half of the hall. “We’d get between 600 to 800 people in the Mt Pleasant Community Centre Hall, and we’d have 10 bouncers … there would be a lot of fights and the toilets would get broken, and you’d have to call the police … but it was a really magical time!

“After the dances we all went to the hamburger bar down Colombo Street or to the Silver Grille steak house down Manchester Street. Very few places would be open and Christchurch was dark. We emptied bottles of Wattie’s Tomato Sauce over everything we ate and at 5am or 6am we’d drop each other off home with love. We never thought of it that way, but that’s how it was.” (A Tinker’s Cuss)

Jim Wilson, teenage dance party promoter. - Jim Wilson collection

These were the good times. Young, bulletproof, and a lot of laughs, but always learning more about the game. By the time Mike and Jim were 18 they had graduated to bringing bands up from Dunedin as well as sending bands down to Dunedin to play at Eddie Chin’s venues. In 2018, Jim recalled to RNZ: “He (Chin) was a fantastic influence on my life and he was a really good man. He was kind and knew a lot about business.”

Lessons were learnt: “I wanted to send a band to Dunedin and he offered me $10 for them to come down from Christchurch.” When Jim would try to up the ante, Chin would point out that the fee should cover the band’s beer and cigarettes, then he would laugh and take Jim across the road to the Dragon Café and buy him a steak to celebrate the deal.

“On these excursions in the vans my mates and me would start laughing in Christchurch and we might have ended up in Rattray Street, Dunedin six or eight hours later still laughing. The Standard Vanguard van – or Bedford – would break down multiple times and yet we’d arrive at Eddie Chin’s club with someone’s pantyhose being used as a fanbelt replacement. They always belonged to the drummer and we always arrived just 15 minutes before the band was due to go on stage. These were some of the best years of my life.” (A Tinker’s Cuss)

Jim learned early on about the promotional power of posters and handbills. Before photocopiers were widespread, printing methods included a Gestetner (stencils) or taking layouts to a firm with an offset machine.

Putting up posters in the late 60s was akin to running the gauntlet. He’s heard the words “you can’t put that there” more times than anybody else in New Zealand. After printing posters on a Gestetner – courtesy of the Canterbury Education Board, where Jim worked in his teens – he and Mike would run around at night pasting up posters and putting flyers under car windscreen wipers.

The posters didn’t always have a long period of visibility: “Back then everyone was having a go at it so you’d get covered a lot and there were a lot of fights … you had to be up first thing in the morning to have your posters on top. Rip It Up editor Murray Cammick said to me once, put the posters up high … you had to have them up high so nobody else could reach them. Or you had to be prepared to put them up in the day time, which was really very difficult, because police stopped you and the City Council would get your registration number and then you’d get a letter … it was a very difficult business.” (RNZ interview)

Jim quickly acquired some serious entrepreneurial skills; he seems never to have shied away from taking a risk. In 1970, aged 19, he took over an inner-city Christchurch nightclub and re-christened it The Joynt. He started booking top live bands such as The Human Instinct, The Underdogs, The Kal-Q-Lated Risk, and The Inbetweens.

“I was really young and I leased the club off Trevor Spitz, who was Phil Warren’s man in the South Island. Trevor Spitz was just all about business. He had fantastic musical taste, don’t get me wrong. He was the same as Eddie Chin really. You learn about boundaries. These guys want to make a buck. So, I went into it and the first night I had a wedding on stage with a couple of my friends going through a fake marriage and I might have had The Human Instinct, I don’t really remember …

Wilson’s accountant looked at the earnings and said, “hmmm, you might just make it at this …”

“But I do remember going to see my accountant in Armagh Street in Christchurch during the week after it and I’d had 600 people on both Friday and Saturday night, and he looked at the figures and he said ‘hmmm, you might just make it at this’ … and I just thought, ‘oh hell, I can’t do that every weekend’. I think about four people had gone broke in that venue before me. Because if you went around the corner in Christchurch you saw the Secrets at the Plainsman, who filled the room four or five nights a week. If you went to Cathedral Square you could see Ticket at Aubrey’s nightclub – and Ticket were a fantastic band. I was naive and I thought everything was about love and all the rest of it, but these were vastly different times. It was a great education. It taught me that noble intentions and good feelings are not necessarily money in the bank.” (RNZ)

The Joynt closed its doors.

Another part of that same education involved dealing with creative musicians and managers. “That’s the hardest thing on God’s Green Earth,” Jim recalled in his RNZ interview. “Dealing with creative people is often very difficult. You want to fill the room and they want to, y’know, make their point, and good luck to them, that’s what they should do. The very best creatives are, at best, unmanageable.”

Some might say that Jim was a little unmanageable himself. Working and living the nightlife came with a laundry list of different distractions. As he recalled in a 2018 email to me, “Nothing to me felt better than standing out the front and watching Phil Judd of Split Enz. Nothing felt worse to me than being in handcuffs. I’ve had both.”

Jim elaborated in his RNZ interview: “When I was young I had difficulty in relationships and I saw people around me begin to use drugs and I was one of the last to go really. I’m talking about intravenous drugs and I joined in after a difficult period of time with a girlfriend. I thought we were all just beat bohemians and the end result of that is I went to jail.

“Jail teaches you a hell of a lot … it’s a great education. A lot of these people in there are really good people. On the outside, you meet people who really should be in jail, but they’re not. I was caught in jail with drugs again and put into the punishment unit in Paparoa. That’s where they take everything off you and shave your hair off. They take your blankets off you at 6am and you’re sitting there by yourself all day. There were two screws, both Vietnam veterans who were running the punishment block, ‘The Pound’ – and they were tough. Once again, you learn lessons from people who are tough like that.

The day of Jim Wilson's release from prison. - Jim Wilson collection

“And then I met a shrink in jail who pretty much helped me clean up my act. I’d asked to see a Justice Department shrink and he came in and I said to him ‘I feel like committing suicide but there’s nothing in here to do it with’, and he said ‘use your teeth.’ That’s one of the biggest life lessons I’ve ever gotten. Y’know, I was depressed in jail and then one day I picked up a book, still my favourite book, Soledad Brother: the Prison Letters of George Jackson, and that enabled me to get angry and anger got me through jail.

“You need it in your life to just get through some of the stuff that happens. You can have all the best intentions in the world and then something happens that you didn’t expect. But if you’re angry and know how to balance that, then nine times out of 10 you will get though. I think the trick is not to become destructive. And, besides, after they’ve punished you that way, what more can they do?”

Upon his release, Jim could see that the local music scene had ramped up. The UK punk explosion had resonated strongly in Aotearoa. A new generation of young musicians had embraced the punk ethic and some of those bands had found a home with Simon Grigg’s Propeller label and Ripper Records, founded by 1ZM disc jockey, Bryan Staff. Roger Shepherd’s Flying Nun label was still just an idea fermenting in the wings at this point. These same bands were being written about in Murray Cammick’s Rip It Up magazine as well as being championed on TV by Dr Rock (Barry Jenkin) and the late Dylan Taite.

It was Taite’s TV piece about the Sex Pistols and the early punk rumblings from the United Kingdom that really resonated. It sparked and inspired a new breed of music that would, within a few years, find an outlet on student radio stations nationwide. These bands built an audience, performing live and promoting their gigs with posters and a DIY mentality that embraced the idea that anyone could play three-chord rock’n’roll.

Jim’s internal antennae tuned in to the excitement that some of these bands were generating with their original material, image and especially attitude. “I got out of jail and I was at a bit of a loose end for a year or two and then I started working for my old mate, Mike Jones. He and Mark Cassin were running Ezzy Promotions in Christchurch, and they were kind of old school, and they were booking the pubs, but they didn’t understand punk.

“What happened to me was that I had a really good friend called Phil Brennan and he took me to see a band called The Vauxhalls [Mark Brooks, Martin Archibold, Scott Brooks] at the Mt. Pleasant Community Centre Hall, and they played ‘I’m Waiting For The Man” in 25 seconds and I just couldn’t believe it … it just excited me so much, so I wanted to take this into the pubs”. (RNZ)

Phil Brennan remembers: “A mate, Tony Blain, and I were putting on dances, as they were called then, at the Mt Pleasant Community Centre. The bands were The Vauxhalls, Stanley Wrench and the Monkey Brothers and Gordon Fitch’s band called The Nameless.

“It was 1978 or 79. Tony Blain went on to own and run the biggest live rock merchandise company in Australia, Acme T-shirts. The week prior, Jim was running a gig at the same venue with some hard rock bands and I asked him to come to our gig the following week. The Vauxhalls had some great songs of their own and covered all sorts, including themes from TV adverts. All played at breakneck speed. They had a solid Christchurch fan base and most of the kids came from the other side of town, on the bus, I guess.

“Jim came along during their set and stood there with his mouth open, blown away by the energy in the hall. Within a year or two, Jim booked The Vauxhalls as openers for The Police and The Boomtown Rats concerts at the Christchurch Town Hall. Shortly after, I was managing The Vauxhalls, and Ezzy Promotions had folded. Jim took over booking the Gladstone and the Hillsborough Tavern. We landed up working together. I was operations and Jim booked the bands and launched some of the best marketing Christchurch music had ever seen. We’d go out late at night and plaster the town with band posters. Jim had a Mini with the back seat taken out that always had posters and a paste bucket in it waiting for a good site. There were numerous issues due to the tightly buttoned-down Christchurch bureaucracy, but the posters always went up.”

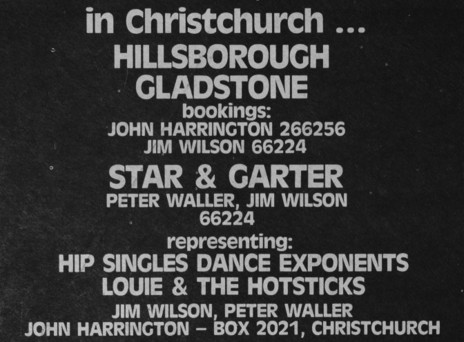

Jim: “I talked to the manager of the Hillsborough [John Harrington] and took over booking his pub. He was a generous man who started Harrington’s Breweries and who had previously been a sausage salesman on the West Coast of the South Island. Then, here he is, he’s got this venue licensed to hold 472.

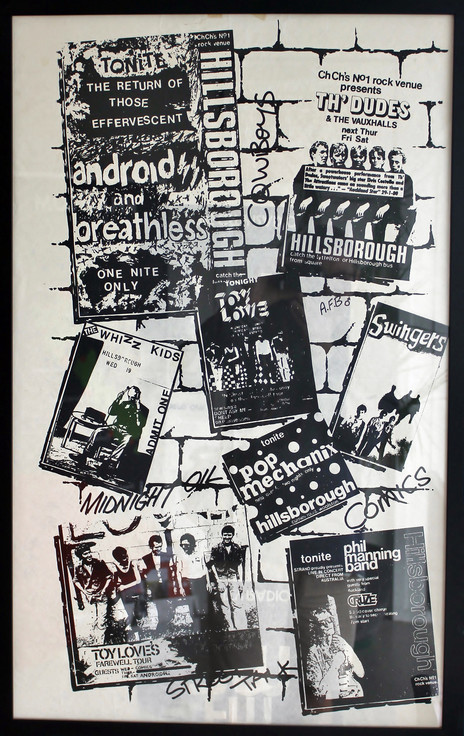

Hillsborough wallpaper. - Jim Wilson collection

“I started booking bands in there and then I started booking the Gladstone as well … all kinds of things happened. John Halvorsen was my graphic designer doing my newspaper ads and posters. Auckland band The Whizz Kids [Andrew Snoid, Mark Bell, Tim Mahon, and Ian Gilroy] were coming through town and I said to John Halvorsen on the Wednesday, from memory, can you form me a band to play at the Hillsborough as support to the Whizz Kids this weekend? He formed The Gordons – and I remember looking at The Gordons and they must have had four or maybe five songs, but they got five or six encores just playing those same songs over and over ... it was just a very exhilarating time cos there were that many good bands around, so it was a ground breaking time for New Zealand music.” (RNZ)

Phil Brennan: “John Halvorsen’s band The Gordons played their first paying gig. Fifteen minutes of the best melodic noise Christchurch had ever experienced. Jim’s feel for things was obviously working well that day. I still don’t know how he did it, but Jim even got an article about their show in the Sunday papers.”

The first Phantom ad, Rip It Up, February 1980.

Painting the city with posters was crucial to promoting these gigs. Murray Cammick recalls: “Touring New Zealand back in the day, you were lucky if the venue had put your band’s posters up. You might arrive and find a big pile of your posters in the pub manager’s office or backstage. You might be asked to sign a pile of posters after the gig. With Jim, you knew the posters would be up and, on the day, they were very visible on your known route into Christchurch!”

Jim: “I watched John Halvorsen doing some of those early Gordons posters and I thought my head would split. Every time I put one of them up, I felt something through my whole body.” (A Tinker’s Cuss)

Christchurch venues and artists booked by Wilson, 1981.

“Bands got a better deal at the Hillsborough and the Gladstone than they got anywhere else in the country and mostly they earned better money as well. I fought for the bands and at both those venues they got several hundred dollars a week spent on radio advertising, and another several hundred dollars a week spent on newspaper ads. I did devastating poster runs and sometimes I even printed the posters as well, screen-printing them on my lounge floor. My idea was to develop the bands up through the Gladstone/Star & Garter and then put them on tour (in the case of the local bands) and then put them into the Hillsborough as headliners. That’s what I did with the Pop Mechanix.”

Phil Brennan: “Jim had a remarkable feel for the real thing and his strong support of any artists he could see some uniqueness in, meant Christchurch became a very financially viable town for many bands. The Swingers played the Hillsborough Tavern numerous times before their single ‘Counting the Beat’ became the biggest-selling single of the year in Australia. If Jim thought a band was worth the effort, there wasn’t anything he wouldn’t do to get them on stage.”

Jim: “For Auckland bands, I saw that they loved coming to Christchurch because they often did better there than they did in Auckland. They went back to Auckland feeling refreshed.

“I also booked a resident band into Doodles nightclub for Phil Warren. I always felt guilty about that because I didn’t have to do any real work except pay the band. So each week I got a cheque for $2250 and I paid the band $2000 and kept the balance. It didn’t seem real. I usually didn’t like the ‘resident’ bands either. But it was at Doodles where I met Chris Sheehan who later joined the Dance Exponents and who was, in my opinion, one of the best things to ever happen to them. Chris came down from Palmerston North to play with a resident band at Doodles. His talent was unbelievable.”

Simon Grigg: “I’m unsure when I first met Jim Wilson, but I think it was probably via phone when he booked The Screaming Meemees to come south on their first trip to Christchurch in April 1981 as part of the Class of ’81 weekend at the Gladstone. We were firm friends from that day onwards and remain so four decades on. Under Jim’s deft guidance, the Christchurch venues were some of the most important in the country and no band could deem themselves successful until they could fill the Gladstone or Hillsborough. But, more than that, he also had an unerring and shrewd eye for what mattered on the edges: Jim instinctively understood musical movements long before they arrived and was not only one step ahead of the game, he often created the game. Jim was, and still is, a passionate friend and ally to musicians, struggling independent labels and those of us in the creative communities who needed support where we could find it. He made a very large part of what we did possible.”

Murray Cammick: “Jim professionally booking and promoting the Christchurch bars was the glue that held the 80s touring scene together. He loved the music and was making it possible for original artists to tour the country. North Island bands such as The Swingers could count on a good Christchurch gig to fund their South Island tour and bands from the Dunedin scene could earn the petrol and ferry money in Christchurch to continue their trip North to play Wellington and Auckland.”

--

Read more: Jim Wilson: an oral biography, part two

<iframe src="https://embeds.rnz.co.nz/audio/2018632414" width="100%" frameborder="0" height="62px"></iframe>

Further Reading

Diary of a Billsticker, part two

Trevor Reekie interviewed Jim Wilson for RNZ in 2018, and by email in 2016 and 2018. Phil Brennan, Simon Grigg, and Murray Cammick comments via email, 2018.