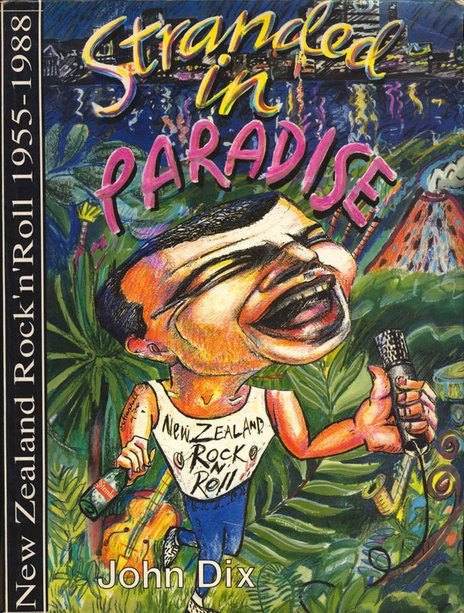

1980 was a pivotal year for New Zealand music with the demise of a number of trailblazing bands, the successful forays into the international market of several others, the arrival of a new crop of young acts, and the resurgence of local independent record labels. I found myself at the coalface of much of this activity, researching a book on New Zealand rock’n’roll, the book that would evolve into Stranded in Paradise.

Stranded in Paradise, the 1988 first edition (Paradise Publications).

At the beginning of 1979 I was living at Snoring Waters, the communal homestead at Waimarama Central, Hawke’s Bay, along with the families of Alun Bollinger, Bruno Lawrence, Geoff Murphy and Martyn Sanderson, and my own young family, wife Dot and daughter Karenza. During an Auckland visit a lucrative offer came my way and for that I have to thank Dolly Rocker.

Dolly was a blower, a telephone advertising salesman, strictly commission, on the dodgy side of publishing – when there’s an egg in town, there’s a meal on the table. It was Dolly who told me about Tasman Publications, a new company looking for writers and editors.

Publisher Geoff Adams and I immediately hit it off and when he realised that I had more experience than he with the publishing process, he employed me as Managing Editor, responsible for a dozen titles, mostly industrial and trade union magazines. Late in the year, at my suggestion, a swag of one-off regional tourist guides was added, fortuitously taking me around the country.

Geoff, a former blower himself, wanted to legitimise his new company and, in time, that was achieved with a professional design team, writers, photographers and editors – and salesmen that actually went out and met their clients. My thanks to Dolly for introducing me to what was a very good earn was to send him and the other blowers packing.

With a full-time position, I required permanent accommodation to house my family, and that too fell into my lap. My good friend Andy Anderson, once one of the wild men of rock’n’roll, had recently abstained from drink and drugs. He had fled the temptations of hometown Wellington and shifted his family to Auckland. His attempts to reform a new-look Andy Anderson Express came to nothing but, an experienced actor and television frontman, he scored a lead role in the short-lived television soap opera Radio Waves. He was the main MC at the Nambassa Festival and sang with Jacqui Fitzgerald in Strange Brew, resident band at Mainstreet Cabaret, also short-lived. He turned his eye to Australia but required a house sitter. The Dix family moved into Andy’s Titirangi home in mid-79.

Meanwhile, I continued contributing music articles to Rip It Up, Rock Express and Australia’s RAM magazine, prompting Adams to suggest a New Zealand music magazine. Partly in deference to Murray Cammick and Rip It Up, that idea didn’t last long and it was Geoff who first suggested a book on New Zealand rock’n’roll. With obligations to Tasman’s growth, the project was scheduled to kick off in the new year, 1980.

Geoff Adams was the unsung hero of Stranded In Paradise, carrying the project for two years and giving me a huge advance and covering many of the expenses. I became fully aware of his generous support during a conversation with my Titirangi neighbour, esteemed author Maurice Shadbolt. “He advanced you how much?” he asked, incredulously. Unfortunately, due to a variety of reasons, Geoff didn’t see the project through but we remained good friends and, sadly, he died of cancer in March 1990.

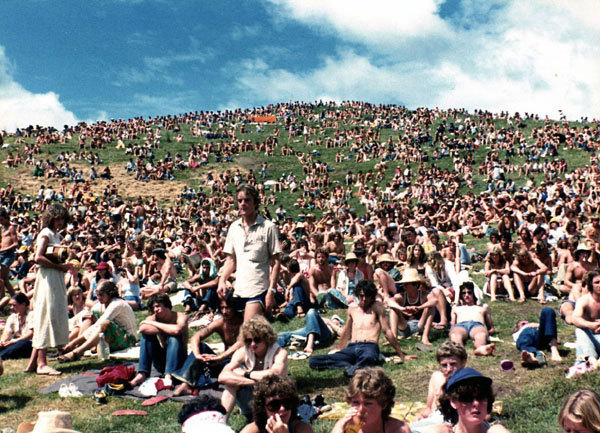

Sweetwaters, 1980

If The Book had a starting point, it was the first Sweetwaters Festival in late January 1980. I first met Sweetwaters organiser Daniel Keighley in 1977 when he was flatting with Snoring Waters habitué Martyn Sanderson in Ponsonby and he’d also visited Waimarama with a contingent of Nambassa Festival organisers, trying to coax Bruno into reforming BLERTA. But my connection to Sweetwaters was due to Radio Hauraki announcer Kevin Black, whose recently formed PR company, Black Marketing, handled the Sweetwaters promotion. With just a five-minute walk between the Tasman and Black Marketing offices, I moonlighted for a short spell in late 1979.

Another festival organiser, Paul McLuckie, had offices on the corner of Karangahape Road and Howe Street, and Black Marketing was confined to one room: three desks, three phones, fax machine and photocopier. Ian Watkin wrote copy for radio ads, I put together a media plan.

Blackie would come in around lunchtime after finishing his Radio Hauraki obligations and roll joints for the team, the three of us carefully smoking up at the window, lest McLuckie walk in on us. Blackie chalked an X outside a phone box across the road, which he rang whenever a likely candidate approached, claiming to be a Post Office technician fixing a problem below – “And if you wouldn’t mind, sir, could you possibly help us test the wiring’s stability by jumping up and down on the X outside?” Blackie considered the sight of some hapless sap pounding the pavement during lunch hour traffic a source of great hilarity. I soon felt like excess baggage myself and concentrated on Tasman business.

When I arrived backstage at the festival there was a problem. With the start time looming, the stage crew had downed tools until the promised deposits were paid. Danny Keighley, busy as, asked me to negotiate and I spent the first afternoon in the ticketing booth to ensure the crew received first dibs on cash sales.

There were many memorable moments over that scorching weekend. In a masterful stroke of marketing, PolyGram Records distributed 20,000 cardboard sun visors bearing the logo for Split Enz’s forthcoming True Colours album, and the band’s premiere of the album was a festival highlight. Toy Love delivered a blistering set, Chris Knox at his most manic and a drunken Mike Dooley at his most frenetic. The Crocodiles’ daytime set launched a successful career and Th’ Dudes unfairly received a barrage of empty beer cans, which only served to fire them up. Dragon’s Paul Hewson beefed up Hello Sailor’s sound but it was a lacklustre performance, a mixture of jaded lethargy and sheer drunkenness. Backstage, headline act Elvis Costello played God, a grumpy prick who alienated everyone he came across, except maybe Barry Jenkin, who delivered him to the festival. His two-hour performance, however, was outstanding.

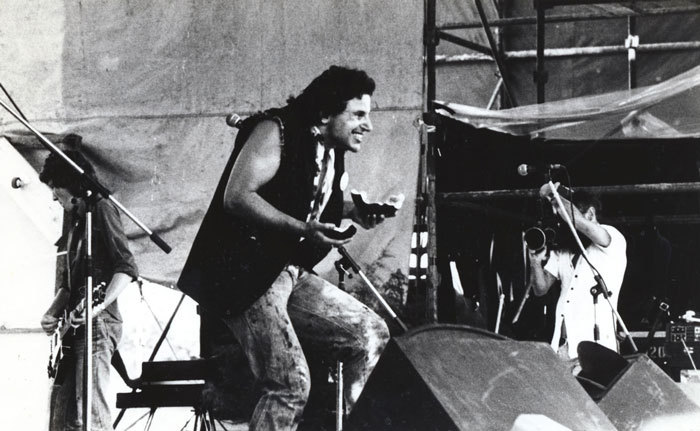

Toy Love at Sweetwaters 1980

I must confess that, without any actual duties, the weekend passed in a blur, backstage mischief was rife. I used the opportunity to put the word out about The Book. Most were keen, others not so much. Steve Gilpin, Mi-Sex’s lead singer and a former next-door neighbour, said, “I’ll have to speak to our management about that.” “What,” I said, “I have to conduct interviews by committee?” Steve took offence, not for the last time over the next 12 months, testing our friendship.

Later in the week I called into Mandrill Studios, where Todd Hunter was producing Toy Love’s second single, ‘Don’t Ask Me’ c/w ‘Sheep’, at the behest of WEA’s Terence Hogan. Hogan was also responsible for the now-iconic artwork for the AK79 compilation of Auckland punk bands. As Simon Grigg has noted, the album captured a moment in New Zealand music which had largely passed by the time of its release but, nevertheless, an early copy provided me with the soundtrack to the summer of 1979-80.

Throughout 1980 I was to become a regular visitor to the Auckland recording studios: Mandrill, Mascot, Harlequin' and Stebbing’s state-of-the-art enterprise in Ponsonby; also EMI and Marmalade studios in Wellington. As any gossip-seeking journalist knows, the best person to speak to is the receptionist and at Mandrill I spent more time chatting with Carol Tucker at the front desk than her husband Glyn in the studio. Eldred Stebbing’s wife Margaret was the best source of information. “I don’t mind the bands using our crockery and cutlery,” she once said, “but I can’t for the life of me understand how Hello Sailor burn the tea spoons.”

Shortly after Sweetwaters, Hello Sailor announced that they were disbanding. Upon hearing the news, I called in to see Graham Brazier, staying with his mother in Mt Eden. “The end of an era,” I said hopelessly. Graham just shrugged, “the time has come, the walrus said … let’s got for a beer, John.”

Sailor’s farewell performance at The Windsor Castle in February was a wild and raucous night and they delivered a near-perfect set that the band themselves regarded as one of their best ever – so good that they briefly considered not splitting up after all. Within days, though, Brazier and Lisle Kinney were back in Sydney.

Meanwhile, Toy Love was getting ready to tackle Australia themselves. Hopes were high for the band but their farewell performance at Auckland University in March was an indication of things to come. Dooley demolished his kit during the encore, annoying the others, not least Jane Walker, who actually owned the drums, and Knox, hit by a flying cymbal. Words and fists were exchanged backstage.

Down at Waimarama, Bruno was preparing to take a hiatus from The Crocodiles. Almost everyone at the communal homestead had an involvement with Geoff Murphy’s feature film, Goodbye Pork Pie, then in post-production. Bruno had done his part, playing the part of a drug dealer; now he wanted to play some music.

The Crocodiles’ star was shining, the debut single, ‘Tears’, had broken through, the album was due shortly and there was talk of an unlikely shift to Holland. Most of the Crocodiles shared a large sprawling house on Grafton Road, Auckland (Bones Hillman and Phil Judd of The Swingers also spent a spell there). I mostly stayed away, feeling a little compromised by Bruno’s audacious behaviour. Not that I was a contender for husband of the year; my son Dylan was born in May. I was present for the birth but within a week I’d legged it. There were other distractions. In Melbourne, Andy had secured a major role in the popular television soap The Sullivans. Homesick, his family, Marilyn and daughter Cristal, returned to Titirangi, and my family returned to Waimarama.

Throughout the year, on the many nights spent away from Waimarama, many friends provided accommodation, from personal bedroom with all the trimmings to a makeshift bed on the couch, and paid accommodation ranged from sleazy motels to four-star hotels.

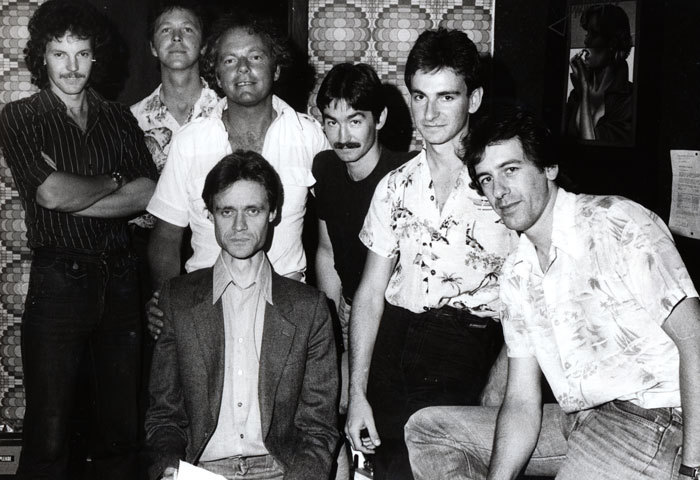

Street Talk at Mandrill Studios, Parnell, with Kim Fowley and WEA Record's Tim Murdoch: Stuart Pearce, Jim Lawrie, Tim Murdoch, Kim Fowley (front), Andy MacDonald, Mike Caen and Hammond Gamble - Murray Cammick

I was staying with Sue and Hammond Gamble in Ponsonby when Street Talk’s Battleground of Fun was launched at Mandrill Studio, the band performing the album for a live broadcast on Radio Hauraki. It was a Sunday night and there were few present, apart from family, friends and a small smattering of fans. To Hammond’s dismay, not one single representative from WEA was present. I mentioned this to WEA head Tim Murdoch the following day. Apparently, the B-52’s were in town and they’d been taken out to dinner. Tim took umbrage when I said, “They won’t be here next week, Tim, Street Talk will. Your priorities are wrong.” He hung up on me. Offending the heads of the multi-national record companies was to become something of a forté in the coming years.

Street Talk split up in September at a packed Gluepot, and the Hammond Gamble Band debuted to a packed Windsor Castle a month later. I was present at both events, again staying with Hammond and Sue. The Street Talk farewell was a remarkable event. Gary McCormick had flown up from Christchurch with his partner Diane Columbus and the five of us passed the afternoon in Parnell. Returning to Ponsonby around 5.30pm, we were all amazed to see two or three hundred people queueing outside The Gluepot, two hours before the doors opened. Street Talk had a fanatical following.

Other top bands divorced in 1980, notably Th’ Dudes and Toy Love, but there were many newcomers on the horizon. Having earlier met manager Will ‘Ilolahia, I was fortunate to catch a very early performance by Herbs at the Ponsonby Community Centre, and I stumbled across a teenage band named Rank & File at a South Auckland garage party. They were hilarious, drinking themselves into a stupor and repeating the same dozen songs time and again into the wee hours. Waltons founder Tim Werry was on guitar.

Rank & File entered a battle of the bands held on Easter Weekend at the Windsor Castle. Rock Quest was organised by Windsor Castle promoter Larry Young and Simon Grigg, avid music fan, record store employee and manager of the defunct Suburban Reptiles. Partly inspired by Ripper’s success with AK79, Simon was starting his own label, Propeller Records. The main Rock Quest prize was studio time at Hugh Lynn’s Mascot Studio, the results released on Grigg’s new label.

The event was held over two days, with about 18 or 20 bands. Judges included maverick DJ Barry Jenkin and Hello Sailor’s Harry Lyon; Simon and I were the only ones who judged on both days. Things got quite messy at the judges’ table. Winners were The Spelling Mistakes, with The Features as runners-up. Propeller released singles by both bands in mid-year. Another promising entry was Wellington’s Ambitious Vegetables, soon to morph into The Mockers.

Two days later I flew to Sydney …

--

To be continued, with tales from the Stranded in Paradise research trips to Australia.

Read more: John Dix – From Pembrokeshire to Paradise