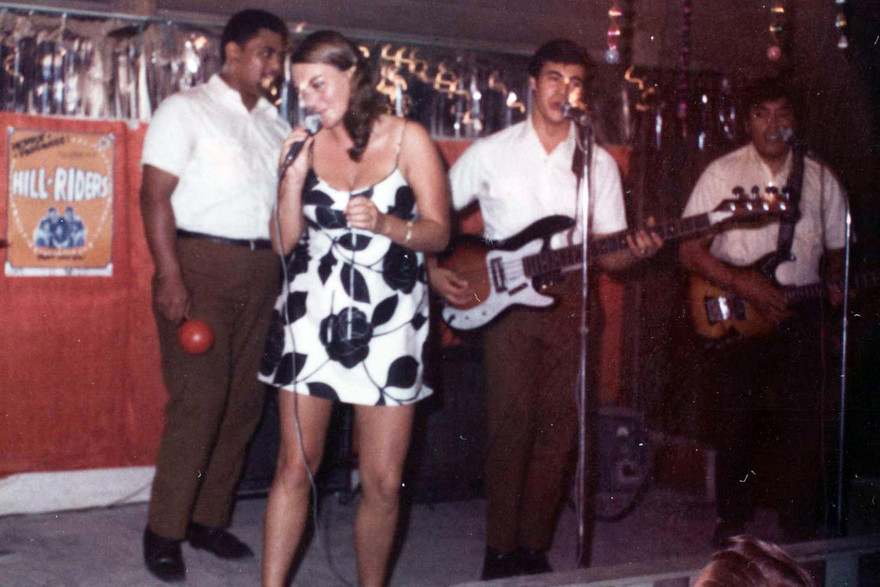

Vietnam, 1969: Ann Pacey performing with the Māori Ambassadors. - Ann Pacey Collection

For many reasons, the conflict in Vietnam came with its own soundtrack.

The war and the music were fed and defined by the young age of the Allied combatants; the turnover of new US, Australian and New Zealand troops arriving; those back from R’n’R leave (rest and recreation) in places like Sydney or Manila with their nightclubs and bands; the portability of records, transistor radios and record players …

That’s why no American film about the Vietnam war since seems complete without songs by Creedence Clearwater Revival (‘Run Through the Jungle’, ‘Fortunate Son’), the Animals (‘We Gotta Get Out of This Place’), or the Doors’ doom-laden ‘The End’, which opened Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film Apocalypse Now.

The Quin Tikis in Vietnam: Weasel Tairoa, Gary Wahrlich, Kevin Rongonui, Freddy Summers, Keri Summers, Sam Mateparae. Photo by Noel Bell

During the war – which ended in 1975 with the evacuation of Allied personnel – there was also the entertainment for the troops near the front line. Many New Zealand artists – mostly Māori showbands – went to Vietnam, performing under dangerous conditions.

“We were performing at a base outside Da Nang on the back of a truck when the fighting broke out,” Mahora Peters of the Māori Volcanics wrote in her band biography Showband!

“Again without warning we were hustled into a foxhole, me still in my skin-tight sequined gown. Upside down I went with no apologies as helicopters flew overhead and the bombs fell dangerously close.”

From 1963 to 1975 more than 3000 New Zealand troops served in Vietnam – 37 killed, almost 200 wounded – although the number of New Zealanders on the ground (fewer than 550 in any year) was small in comparison with the hundreds of thousands of Americans and more than 50,000 Australians.

What these men and women wanted in their downtime in Vietnam – usually on well-guarded military bases or in the fleshpots of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) – was entertainment which allowed them to escape their reality for a while.

And that is what the Māori showbands provided: a mix of mainstream popular hits, standards, some tear-jerkers and – for the women performers – costume changes. It was all served up professionally and with flashes of humour: a full, professional entertainment package. A tonic for the troops.

The Māori Volcanics did four tours in Vietnam: “It was great experience,” Billy Peters told Piripi Walker for RNZ in 2005. “But we were doing 21 shows a week, so that’s three shows a day. In that heat. When you got on stage your uniform from the previous show was soaking wet already. Even if you had three uniforms you couldn’t keep them dry. So you went on in this cold, wet outfit.”

The 1RNZIR band plays for New Zealand and Australian troops amongst a rubber plantation at Fire Support Base Discovery, 28 October 1969. To attend the short concert the soldiers had to emerge from their jungle hideouts. It was well appreciated, said bandmaster Major Jim Carson, as their "lives get somewhat tedious where long patches of time are endured between actions." - VietnamWar.govt.nz

Among the New Zealand many entertainers working in Vietnam were showbands such as the Volcanics, Quin-Tikis – and a 19-piece Dixieland jazz band of the 1st Battalion Royal NZ Infantry Regiment.

Dinah Lee, her ‘Blue Beat’ days behind her and living in Australia, also performed there under her own name Diane Jacobs, and was subsequently awarded an Australian Vietnam Logistic and Support Medal (established in 1993). She made two tours to Vietnam, in 1966 (including concerts at Luscombe Field in Nui Dat), and again in 1969, after which she stayed on privately (and unpaid) in Vung Tau. Her brother Peter served as a lance-corporal in Vietnam with the RNZIR.

Dinah Lee on stage with an Australian soldier, Nui Dat, Vietnam, 1967. - Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-4801-1-20

In a 1993 oral history with Roger Watkins, Lee’s memories were mostly buoyant: “I loved it,” she said. “We were looked after ... You were treated as generals, type of thing, bodyguards, they made things for you – if there wasn’t a toilet they’d make one, you know, for the girls. They’d do anything for you – beautiful food, officers’ mess, wonderful. They couldn’t do enough for you. So that side of it – the fun side of it – yes. But then, you know, we’d go and visit the hospitals and the people that were – the young guys that had been injured, and you know, and then we saw that side of it. So, you got to see these young guys – they don't know, they’ve just come back and some of their mates hadn’t [returned] with them.”

To Mahora Peters of the Volcanics, entertainment may have been the job but the real world was always there: “We’d been around long enough to know you could get killed anywhere.”

“One of the saddest memories is singing to 18-year-old soldiers in Vietnam today and then hearing they were killed tomorrow,” Ronnie Ransfield of The Sheratons told the Rotorua Daily Post in 2016.

“It was very sad to stand on the airport terminal and watch 500 to 1000 alloy caskets being shipped home to be buried. I couldn’t bring myself to photograph that.

“Hearing gunfire and bombs going off while you are performing was nothing out of the ordinary. But we were young and had no fear.”

At the time Ransfield was one of 13 Vietnam entertainers being honoured with a service medal similar to that of the Australians. In 2016 New Zealand artists who had entertained the troops during the war were deemed eligible for the New Zealand General Service Medal 1992 (with clasp “Vietnam”) and the New Zealand Operational Service Medal.

Members of the Quin Tikis (band leader Sam Mateparae – the older brother of Sir Jerry Mateparae who was Governor General 2011-16), the Māori Tikiwis, the Māori Ambassadors, the Māori Volcanics, the Māori HyMarques, the Māori Minors, the Tikiwis, the Māori Te Pois, and the Māori Travellieres showbands – some contracted by the United States Service Organisation – were encouraged to contact the New Zealand Defence Force to confirm their eligibility.

Veterans who entertained troops in Vietnam, and some relatives, receiving medals for wartime service at Government House, Auckland, 20 July 2016, with Governor-General Sir Jerry Mateparae. Dinah Lee is fourth from left; among the others present are George Emery (receiving on behalf of Lenny Thompson, Māori Te Pois), David Mateparae (son of Sam Mateparae of the Quin Tikis), Paul Naera (Māori HyMarques), Mrs Mahora Waaka (Māori Volcanics), David Rivers (for Phillip Rivers, the Tikiwis), Terence Sorenson (The Sheratons), Pamela Waaka (for Nuki Waaka, (Māori Volcanics), Maurice Watene (for Arapeta Watene, Māori Te Kiwis), and Katrina Werahiko (for Herewini Selwyn Rawiri, Māori HyMarques). - Government House

If a member was deceased, a family representative was encouraged to contact the NZDF to accept the medals on the member’s behalf. “It is especially poignant for those families of the entertainers who have passed,” said Lieutenant General Tim Keating, the Chief of Defence Force. “We hope that the families will view these medals as we in the NZDF do, they are taonga inherent with the mana of the person they are awarded to.”

July, 2016: Governor-General Sir Jerry Mateparae presenting Dinah Lee with the New Zealand General Service Medal 1992 (with clasp “Vietnam”) and the New Zealand Operational Service Medal. - Government House

The award was not without its critics – many using the online platforms to express their outrage – who questioned whether entertainers deserved such an honour. But many performers spent considerable time in Vietnam – the HyMarques were there from August 1971 to March 1972, the Māori Volcanics did four tours – and at a time when the war was at its peak.

Mahora Peters spoke of shows being halted by mortar fire: “Many times, especially up in the DMZ [de-militarised zone] where you’d be performing on the back of a truck.

“They’d pull a big truck and you’d set your gear up [on the tray] and they’re firing over onto the hilltops and they’re firing back. They’d say, ‘Hey, get those entertainers out of here’ so sequinned gown and all I just piled into the back of a helicopter, and off we’d go.

“We went the first time in ’68, ’69 and it was pretty rough then, pretty rough for women, no facilities or anything like that. We got shot at several times and dodged some bullets.”

Ann Pacey in Vietnam while with the Māori Ambassadors, 1969. - Ann Pacey Collection

Among those who received the medals was Ann Pacey who, while performing in Sydney with the Māori Ambassadors, was approached by a US booking agent. For the first three months of 1969 they played two or three shows a day at Cu Chi Base, northwest of Saigon in southern Vietnam. In 2016 Pacey recalled her tour of duty to Stuff’s Brad Flahive:

“We were making about US$500 a week, which at the time we didn’t think was enough, but there wasn’t much we could do about it. We entertained everyone from officers to airmen, Americans, and all nationalities. They really liked hearing meaningful ballads, songs like ‘(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay’ were popular.”

Pacey also mentioned the danger the entertainers were in: “I came back to the villa after being away and found a bullet hole in the wall by my bed – right where my head would have been. We were always told to watch out for bombs. Apparently they were set in the rat traps around the camp.”

The Tikiwis performing at the Logan Park Motor Hotel, Auckland, in October 1967. In January 1968 they arrived in Vietnam for a six-month tour. From left: Philip Rivers, Paul Watene, Helene Johnston, David Rivers and Winiata (Wini) Watene. - Rykenberg, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-19671031-07

Philip Rivers of the Tikiwis remembers being just 20 at the time, about the average age of the American soldiers in Vietnam. “The day we arrived in Saigon they were celebrating the Chinese New Year, letting off crackers. But as night came you could hear the explosions change to rifle shots. We knew then that we’d arrived.” On his return to New Zealand he said the trip was profitable but not worth the risk.

Mahora Peters had some “really warm beautiful memories” and, after finishing a show in coastal Vũng Tàu near Saigon, “we were heading back out onto the helicopter which the Americans had supplied for us and all the Māori guys came out bare-waisted and did the haka. There was about 100 strong.

“We had Prince Tui Teka with us then and all the other guys. We were on tour, we’d done all of the Asia we were heading after that for Europe across the Middle East and then to Belfast.”

The Māori Volcanics doing their broken glass act, with Mahora Peters, Nuki Waaka, John Nelson, Gilbert Smith and Prince Tui Teka.

Paul Naera – leader and drummer in the Māori HyMarques and the Ambassadors showband in the 1970s – was a major supporter of the late HyMarques saxophonist Herewini Rawiri’s crusade for recognition of the groups’ service in Vietnam, and provided the research needed to identify members of the showbands.

Naera says, “We were just looking for adventure and we sort of didn’t worry about our welfare and we just went there to entertain and enjoy ourselves.”

Other musicians were in Vietnam-adjacent locations: Peter Nelson – formerly of Christchurch’s Castaways in the mid 60s – found himself entertaining emotionally stressed, but ready to party, US airmen on R’n’R in Bangkok. Others did the same in the clubs of Sydney’s Kings Cross. In Manila, trumpeter Kim Paterson was part of an 11-piece soul band playing to US troops on furlough.

Vietnam was part of the collective consciousness in New Zealand: volatile demonstrations took place during visits here by South Vietnam’s Prime Minister Air Marshal Kỳ in 1967 and US vice-president Spiro Agnew in 1970. The issue dominated headlines and nightly news as the body count rose and street protests became more voluble.

Auckland students protest the Vietnam War at a capping procession up Queen Street, 1967. - William H Tinson, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1714-R002-27

However there were very few anti-war songs from local musicians: notably absent were the underground musicians. One who did respond was Red Mole co-founder, poet Alan Brunton, who attended the Spiro Agnew protest. In 1978 he recorded his ‘Viet Vet Blues’ backed by Red Alert.

Ironically then, mainstream singer Craig Scott took the Australian anti-war ballad ‘Smiley’ (“you’re off to the Asian war ... and we won’t see you smile no more”) to the top of the local charts in 1971.

“No more laughter in the air. Feel the tension in the air. When will they learn?”

Radio New Zealand’s Māori Showbands series, by Piripi Walker, 2005

Read more: Ann Pacey on her time in Vietnam, Stuff, 2016

Read more: Dinah Lee talks to Roger Watkins about her stints in Vietnam, 1993

Read more: New Zealand’s Vietnam War (Ministry of Culture & Heritage)

Responses to this article

Will Nuku – Kia ora koutou! I was part of a band from Aus called “Electric Flower” that did a brief stint of Vietnam at that time. We were flown by helicopter to the front line and performed down in a bunker for guys whom had just returned from battle still wearing their packs. It was both bizarre and frightening at the same time. We felt honoured and privileged to have given them some form of comfort as it were, especially when we ended with “We gotta get out of this place ...”

Rewi David – Thanks to all the service men and women who went over there to serve ...great musos. I was with two of them last night for a jam who entertained troops in Vietnam late 1960s, they’re almost 80 now ... for those who dont know the calibre of these New Zealand show bands, Barry Gibb used them as a template for the Bee Gees when they toured through Brisbane in the 1950s and 60s. I was always anti war but that does not diminish these musos in anyway.