AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

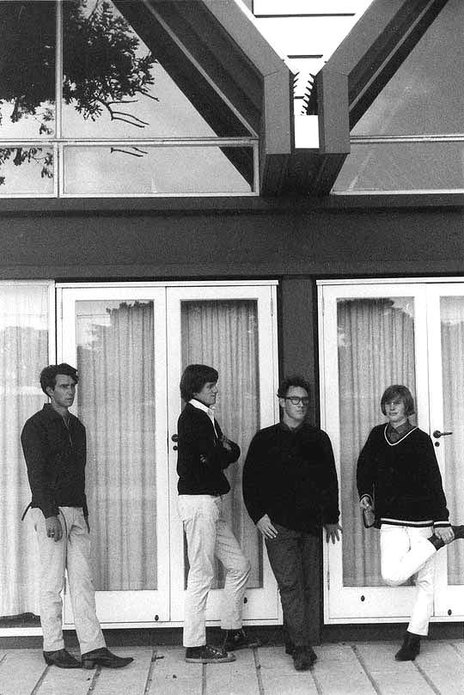

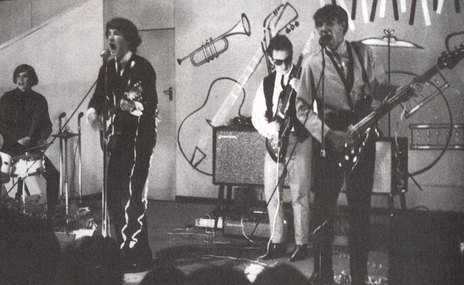

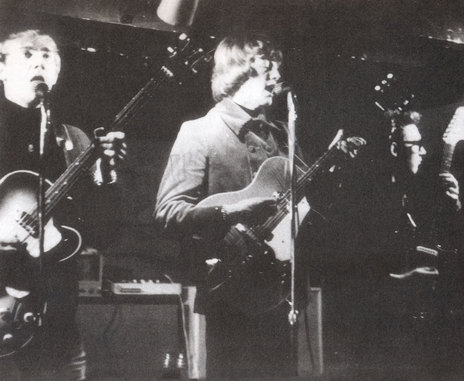

Chants R&B

Keenly awaiting the band and some more outrageous behaviour, no doubt, were TV camera crews, press and fans.

Suddenly, there they were: a small gaggle of long-haired, modishly dressed young men ambling across the tarmac.

The cameras clicked, the TV crew zeroed in for an interview, the fans roared, and the four young guys on the tarmac wondered what the hell was happening. They were a band all right, and massive Pretty Things fans, playing many of their idols’ songs and generating wild stage presence with a similar frenzy. But the young guys were Chants R&B, a Christchurch R&B outfit.

Later, after the Englishmen heard of the band’s local reputation, they were asked to join The Pretty Things on stage. Chants R&B declined, a little overawed by the offer.

Twenty-nine years later, this anecdote is modestly told by original Chants R&B guitarist Jim Tomlin. And yet in their own backyard, The Chants were as much an influence as The Pretty Things.

When the awe passed, they returned to a scene every bit as potent (although on a much smaller scale). Just as The Pretty Things were influenced by the black rhythm and blues masters, Chants R&B were a musical ripple of the English tourists and their brethren’s influences.

The history of rock music is full of such moments, when innovative sounds grab the imagination of young musicians, who want to emulate them, and fans, who want to dig the sounds live. All they need is a focus. A venue. In turn, that fusion of style, moment, music and home breeds a scene. In such a way a scene was born in Christchurch in the mid-1960s.

The Chants

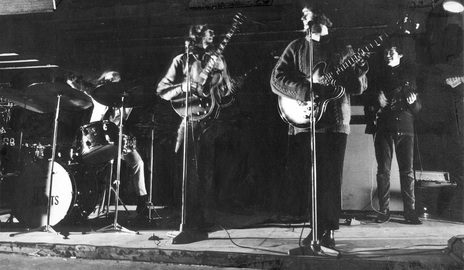

The Chants, a young quartet weaned on The Beatles and the chart R&B of English bands such as the Animals, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks and Manfred Mann, then further galvanised by the snotty white R&B of Them, the Pretty Things, The Downliners Sect and Graham Bond Organisation, and an array of lesser lights, made the Stage Door, a basement club in Hereford Lane, their own.

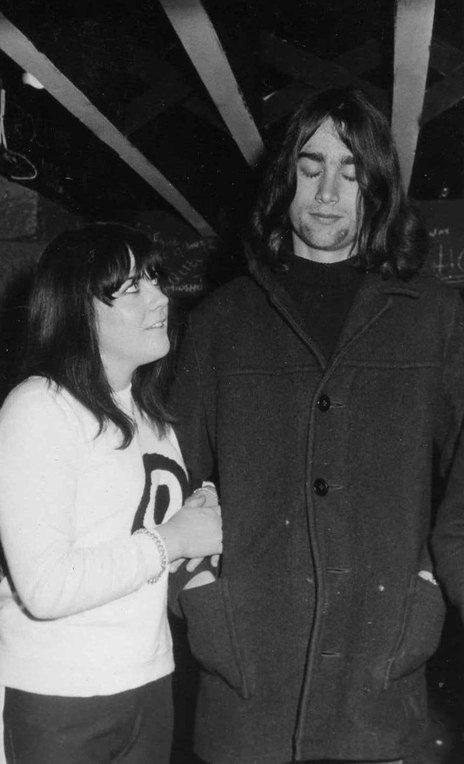

The club had the sweaty, urban air of The Cavern and Crawdaddy Club and became a meeting place for Christchurch long hairs (sometimes called mods, but no relation to the English version), the stylish teenagers who were aping the long hair and changing fashions of swinging London.

For two years The Chants (later Chants R&B) held sway in the dank black interior of the Stage Door, playing a mix of tough R&B and soul.

The club was still down there as late as the 2011 Christchurch earthquake; its raised concrete stage intact. Its black painted guts are scarred with scratched and painted graffiti on its rafters and walls proclaiming “Clapton is God” and “Mayall is Jesus”. Dylan gets a name check too, while hardcore fans have tagged their names up in the crossbeams. Down the back in the corner where the original alleyway entrance was located, “PGT is Fun but Hash Fred is Heaven” is scrawled cryptically.

Its black painted guts are scarred with scratched and painted graffiti on its rafters and walls proclaiming “Clapton is God” and “Mayall is Jesus”.

The thought of those long gone fans raised a smile out of The Chants’ original guitarist, Jim Tomlin, when he was tracked down to his Dalmore, Dunedin residence in late 1994.

“Thirty years,” he mused, casting his mind back through a teaching career which has culminated with his tenure as Head of Otago Polytechnic’s well regarded Art School.

Back in 1964, he’d just returned from Auckland and was teaching art at Lincoln High. The Lumsden-born Tomlin was no stranger to live performance. In his early art school days he played guitar with a group of friends called The Artists – including Ishwa Gandha (vocals), Barry Walsh (drums) and Brian Wright (bass) – prior to that he’d plinked piano with a dance band and skiffle group in Invercargill, where he attended school.

At Auckland Teachers College, Tomlin learned jazz guitar and mixed his contemporary R&B tastes with the likes of Cannonball Adderley, Wes Montgomery, the Modern Jazz Quartet and Charlie Mingus. Back in Christchurch, he joined a Beatles influenced band with quiet art student Mike Rudd (guitar/vocals/harp) and extroverted 15 year-old drummer Trevor Courtney. With Rudd’s former schoolmate Compton Tothill on bass and Stan Major blowing sax, they soon dubbed themselves The Chants.

Compton and Stan left, replaced by former Dynamics bassist and early long hair Pete Hanson (older brother of Ticket’s Eddie).

Trevor: “I remember Mike coming over with the first Rolling Stones album. I’d heard their version of Buddy Holly’s ‘Not Fade Away’ and thought ‘Jeez, this Mick Jagger can’t sing’, then Mike whacked the album on and it just blew me away.

It wasn’t long before Christchurch got a sample of the power and chemistry that would make The Chants special when the band won the 1964 Battle of the Bands at the Addington Showgrounds. All the more surprising that it was their debut performance. First prize was a TV performance and a recording session for HMV Records at Avonside Recording studio where the band recorded covers of ‘King Bee’, ‘Empty Heart’, ‘Baby, Can I Take You Home’ and an original, ‘I Forget How It’s Been’.

The songs weren’t released at the time as the band thought them unacceptable and they were long thought lost. Luckily one track, the frenetic beat number ‘I Forget How It’s Been’ was recently discovered hidden on a live tape of the band.

Despite their early success, The Chants had only played a few school dances and the odd show at venues such as the Plainsman Hall and the Art Students Ball, when Mike Rudd happened upon a strange sight in a basement off Hereford Lane one day in late 1964.

The King Bee

“When I discovered the King Bee (Koffee Kellar), Steve O’Rourke (now an Australian TV actor) was leading a conga around a dingy looking basement reminiscent of the Cavern. I think I joined in and played a little harp to general acclaim and decided this was the place.”

When I discovered the King Bee (Koffee Kellar), Steve O’Rourke was leading a conga around a dingy looking basement reminiscent of the Cavern.

The King Bee’s ads proudly announced – “We go until you go” – and rejected the presence of “finks or plebs”. It was opened in late 1964 by John O’Brien and Paul McGarry. O’Brien was bassist with the club’s first resident group, The King Beats, a suitably Stones-ish combo for the self-proclaimed “true home of rhythm and blues”.

The Chants, when they took up their residency there, were changing rapidly. For one, Pete Hanson had been replaced by 17-year-old Martin Forrer, a veteran of surf band, The Invictas, and cover bands The Satellites and The Esquires. The Chants also had a toughened set, featuring more Pretty Things, Graham Bond Organisation and John Mayall numbers.

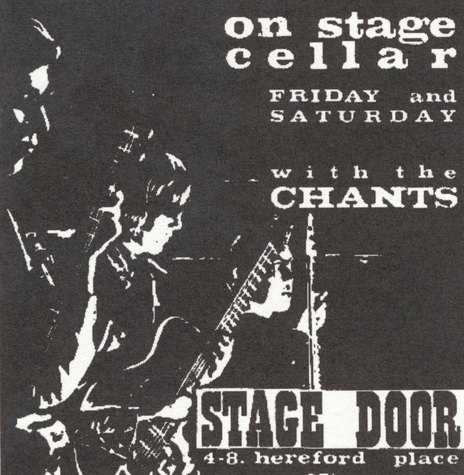

In August 1965, the King Bee was sold to Des Monaghan, Gordon “SPUD” Murphy and Tony Walmsley, who had planned to turn it into a hangout for the acting profession. They renamed it the Stage Door. Cue another name change. Enter Chants R&B.

The change had little impact on the club’s musical activities. Chants R&B still played their four-hour Friday and Saturday night sessions, later adding a special Sunday afternoon dance.

Folk nights, featuring local folkies Phil Garland, Tony Brittenden and Rudd and future wife Helen, were still happening, but now punters, if they so desired, could catch Pat Evison (Close To Home) reading poetry or sit in on the Stage Door’s theatre productions.

Downstairs, things cooked. Chants R&B, benefiting from playing frequently and the avid record importing of Rudd and Courtney, were chopping out wild sets chock full of songs not then released in New Zealand. Alongside re-bored R&B, early Chess and Atlantic soul sides crept into the set, alienating some hardcore R&B fans.

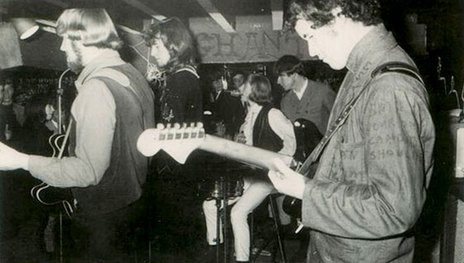

Onstage, the Chants raved it up. Hyperactive drummer Trevor Courtney swung from the rafters on his set pieces – The Downliners Sect’s ‘Cops and Robbers’ and Napoleon XIII novelty song ‘They’re Coming To Take Me Away Ha Ha’ – sometimes swinging forward onto Rudd’s shoulders, causing them both to collapse into a raucous heap. While out to the side, sandy haired bass player Martin Forrer sat cradling his semi-acoustic Epiphone bass in front of his amp as waves of rumbling feedback washed over him. Beside him, guitarist Tomlin took a more studied approach to his craft, his Cossack fur cap the only sign of eccentricity.

There was some method to the madness. During the band’s elongated rave-ups Trev’s mate Noddy would slip in behind the drums to keep the beat going. The band’s early use of strobes just added to the frenzy as Mike and Trevor smashed up cheap guitars and tambourines in the fractured light, a trick they’d learned from The Pretty Things’ Christchurch show.

The club was often crammed to its 200 capacity with long hairs, students, and those Mike Rudd remembers as “dissolute kids, schoolgirls, the unemployed and the unemployable".

Half the time, the crowd just stood around the stage soaking it all up, while down the back on the couches social intercourse (anything more and you went behind the curtain by the pump) bubbled to the sounds. Those who had it nipped on concealed hip flasks of sly grog.

The more adventurous tried something stronger – pills, pot from the wharves or morphine sulphate lifted from lifeboats.

As with most bands, the Chants had their hardcore fans. In their case, the long hairs, avid followers of white R&B sounds and swinging London fashion.

The band’s early use of strobes just added to the frenzy as Mike and Trevor smashed up cheap guitars and tambourines in the fractured light.

It’s hard now to imagine what an impact long hair had on straights in the mid 1960s, but one-time long hair John Dalton remembers constant hassles and being asked to leave a job because of it.

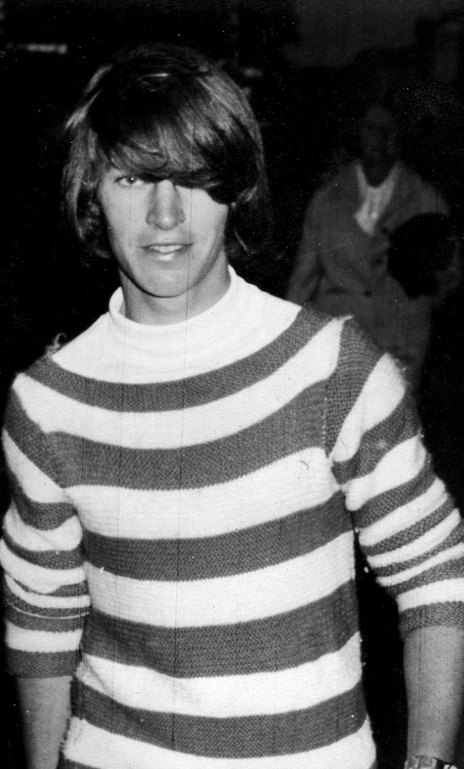

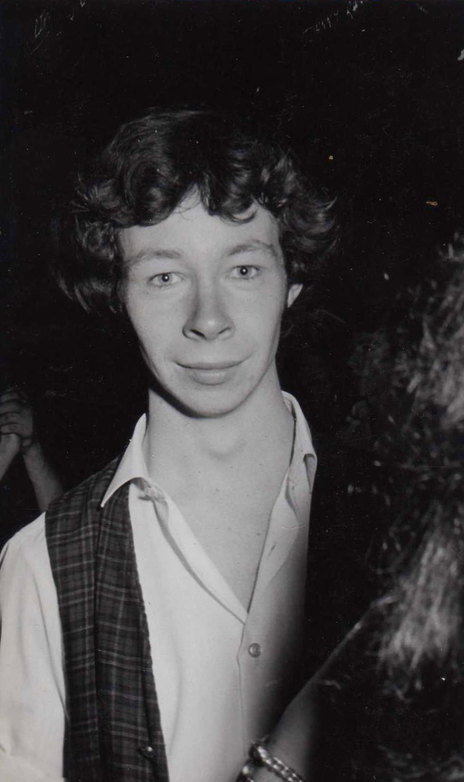

Lucky Trevor Courtney somehow managed to get a temporary dispensation from his high school to grow his hair long – because he was a musician (!), and because the stubborn Courtney refused to cut it, even after numerous suspensions.

Courtney: “It used to be quite a hassle. I had a very good supply of Brylcreem so I could brush it back, but it wasn’t allowed to go over my collar. The headmaster called me aside one day and said ‘Look, I know you’re in a band on the weekend, you can grow your hair long.’ I was doing real well at school coming top of my class and all that shit, so it wasn’t affecting my schoolwork. Then three months later he pulled me up in front of the Board of Governors and tried to get me expelled.”

In July 1966, a thoughtful feature in The Press, Christchurch’s conservative morning daily, even pondered the problem in a piece subtitled “Long Hair – a reflection on youth or society” alongside photos of Chants’ fans John Dalton and Paul Fisher.

Style and confrontation ...

There were few better dressers in the Garden city either. Martin Forrer remembers: “There was an English tailor, Les Sherlock, who had a shop called Bourne’s and he’d make mod clothes, lacy shirts and waistcoats you couldn’t buy here.” This made the long hairs stand out all the more. Rudd even appeared as a model in the shop’s catalogue.

It wasn’t just the older generation who had problems with modish hair and dress. Teenage Christchurch was awash with music-related factions.

Dalton: “There were three factions. The surfies, rockers and mods (long hairs). Mods hung out at the Stage Door and surfies at the Surfari Ballroom at Brighton Beach. Rockers went to the Plainsman Hall and argued with everyone. They’d go down to the Surfari and fight the surfies (we went down there also at one stage). Rockers incorporated V8 boys and were the forerunner of bikie gangs in Christchurch.”

The tensions often flared into violence with rockers haunting Hereford Lane looking for heads to kick.

Rudd: “It was Sunday afternoon sport for the bikies to come down and beat the crap out of us as we walked out of the Stage Door, or threaten to. I dunno if it happened that much. I got grabbed at one stage and they abused the crap out of me. I didn’t respond, so it took all the fun out it for them, I guess.”

Courtney: “They preferred beating up the army in the square, or the police.”

But not always. Long hair/rocker tensions reached a shocking climax when a young rocker was killed in a Christchurch suburban street during a confrontation with mods in late 1966.

That didn’t stop the long hairs indulging in standard teenage hi-jinks like drunken car journeys (outside the car) over the Port Hills to Lyttelton, or tearing around Cathedral Square.

It was an exclusive club, wannabes who didn’t make the grade were dosed with laxative-laced chocolate. The long hairs treated the Stage Door as their own, waltzing past the karate club bouncers without paying, claiming proprietorial rights on the best spots down the back, and staying behind after the Chants had wrung the last sainted note out of their set closer, the Graham Bond Organisation’s ‘Early in the Morning’.

Which it was by then. Afterward, the gang would take off for parties specially delayed so the Chants could attend, or to the Regent Coffee Lounge for food and coffee, then home for sleep only to be back down at the club for the next day’s afternoon session.

The studio

After a year at the Stage Door, the Chants turned their thoughts towards recording. Enter Paul Marks, who had visions of a corporation based around the Chants’ recording output, and related products such as the Bernie Bisphan-invented Action fuzz box.

Bisphan, a teacher by day, had created the fuzz box by detuning a transistor that altered the guitar’s signal to its amp. When they worked, they worked well, but the quality varied according to the tuning achieved. Bisphan also built the band’s amps.

Both Tomlin and Bisphan invested money in the venture, money they never saw back, as Action seemed to be lacking just that on the financial return front. Rudd and Courtney have few fond memories of the Bisphan inventions or Paul Marks.

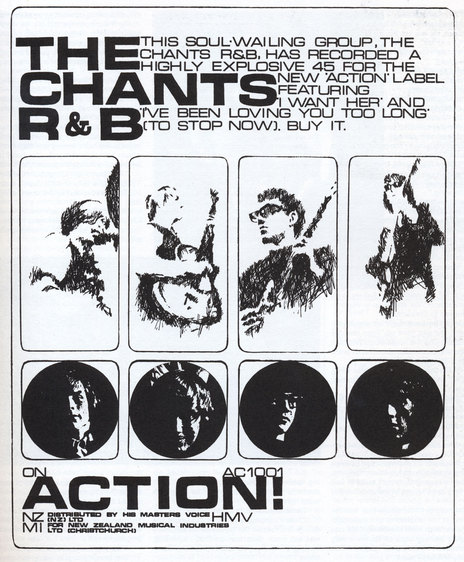

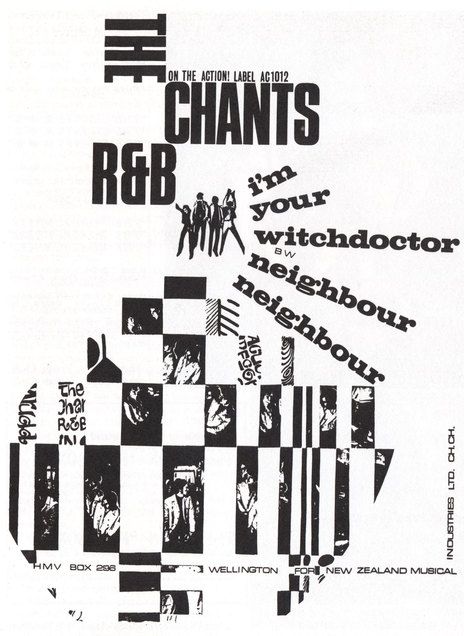

In early 1966, Chants R&B recorded their first 45 on a 2-track machine at 3YA, a local radio station. Otis Redding’s ‘I’ve Been Loving You Too Long’ backed with their own ‘I Want Her’ was released in March on Action Records with a Mike Rudd-designed sleeve and logo. The single sold well around Christchurch.

Rudd: “l was a big Otis fan, but you wouldn’t know it from listening to the record. I sound like an ex-chorister, which is what I was. I suppose it was a unique approach, but it didn’t have anything to do with Otis Redding.”

‘I Want Her’, Jim Tomlin remembers, “was probably one of the weirdest local compositions ever heard. At times it’s out of time, out of tune and instead of a guitar solo I played an Indian snake charmer’s flute I’d recently been given.”

"Instead of a guitar solo I played an Indian snake charmer’s flute I’d recently been given."

– Jim Tomlin

The song, descended from a live Pretty Things influenced rave-up, was sung with spontaneous lyrics by Trevor (although he managed to slip a line from Van Morrison’s ‘Little Girl’ in) and was the only original Chants R&B song ever released.

It was also the last time Jim Tomlin recorded with the band. In the middle of the year, he slowly phased himself out of the Chants, having found the effort of playing eight hours, practising and learning two new songs a week too much on top of his teaching job. His steady influence would be missed.

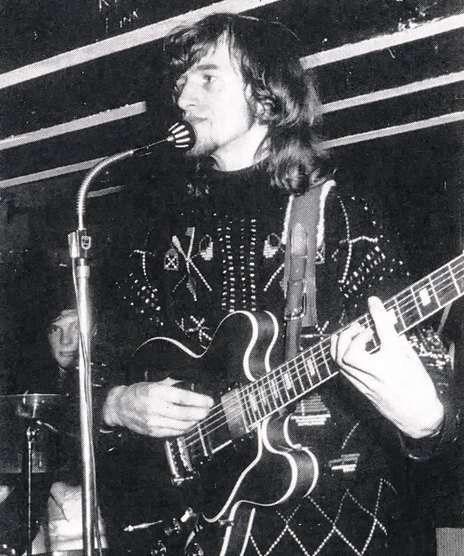

His replacement was the mysterious Max Kelly, a young Australian who’d sometimes jammed with the Chants. Kelly, quickly dubbed “the fastest guitar in the west”, brought a different style of playing to the band. Where Tomlin was a more soulful guitarist who played lots of long notes, which tended to bleed out and wail, Kelly was fast, his notes blurring all over the place. In Martin Forrer’s words, “like a hyperactive bumble bee”.

Forrer: “When Max joined, the sound of the band changed: it got bigger. He locked in musically and was really fast, played notes right through the song.”

So how did a crash hot Aussie guitarist end up in mid-1960s Christchurch?

Kelly: “I’d been in the Australian Air Force and played in a band called The Bluebeats. We used to do all these Yardbirds and Shondells numbers. I’d finished my time, so me and a mate decided to start a band called The Kelly Gang and move to Sydney. It was a spur of the moment thing then he said ‘No, we won’t go to Sydney, we’ll go to New Zealand.’ We ended up in Wellington then moved to Christchurch.”

After several unsuccessful attempts to form a Kelly Gang, the pair gave up. Then one day they stumbled upon the Stage Door. With Jim Tomlin intending to leave, the Chants were looking for a new guitarist.

Local DJ Les Pringle suggested Kelly, who tried out and got the job. The admiration was two way.

Kelly: “I’d come from Melbourne and had seen The Easybeats and they were tame by comparison. No Australian band was playing that kind of material.”

It all seemed too good to be true. It was. Max Kelly had a secret. He was really Matt Croke, and he was AWOL from his employment as an apprentice with the Australian Air Force and his past was soon to catch up with him, as Mike Rudd found out early one morning when roused from his Cashel St bed by “some very large blokes in trench coats and boots.”

“They wanted to know where Max was (he was working at the wool stores to supplement his meagre earnings with the band).” He was soon winging his way back to Oz for a very uncomfortable two-week sojourn in Holsworthy Barracks.

Croke believes his mother informed the military police of his whereabouts and new name. Luckily by then, Croke had already played his part in recording the two songs on which Chants R&B’s huge reputation would rest.

Out of Christchurch

On one of only two excursions out of Christchurch – the first being a trip to seaside resort Timaru to play at the Mods Ball in the city’s “floating ballroom” – the band traveled in June 1966 on the Lyttelton ferry to Wellington to record their second single at the Windy City’s HMV studios. With them went Jim Tomlin and a hardcore of long hairs.

Tomlin sat in as producer on the five tracks recorded (‘I’m Your Witchdoctor’, ‘Neighbour Neighbour’, ‘Mystic Eyes’, ‘Come See Me’, ‘Early In The Morning’), though in effect he was more a sympathetic pair of ears in the recording booth.

The recording went well and the band looked forward to their second single, again on Action Records.

Before they left Wellington, the band played five gigs in two days, organised by Paul Marks. They stunned the locals to silence in Upper Hutt, where they played with The Roadrunners. In the city at The Place, they moved an impressed Reno Tehei (Sounds Unlimited guitarist) to proclaim them “Wild, man”. No small compliment from one of NZ rock’s wild men. Legend has it that Rudd nailed his feeding back guitar to the floor at one wired outing, although Rudd remembers it differently. He spared the guitar, impaling the guitar strap instead. From the audience, it all looked the same.

The eventual single ‘I’m Your Witchdoctor’, a John Mayall number backed with ‘Neighbour Neighbour’, was a big disappointment to Jim Tomlin when it was released in December 1966.

“At the time I thought we’d done quite well. One track in particular, when it was recorded, was shattering, and that was ‘Witchdoctor’. But something accidentally happened between recording and pressing. We were quite upset when that record came out. ‘Witchdoctor’ was scratchy and shrieky sounding. Where it was originally rich, with a lot of depth to it, it now it sounded like a fuzzbox went right across it.”

Those damned fuzz boxes again.

Croke: “I shoved a piece of rag under the strings and turned the guitar down but there was too much distortion on that. Too much whistling, farting, shrieking, you couldn’t use the damn thing.”

"Too much whistling, farting, shrieking, you couldn’t use the damn thing."

– Matt Croke (AKA Max Kelly)

Tomlin was less disappointed with ‘Neighbour Neighbour’, regretting the prominence of the bass in the song’s mix, his idea he admits.

Perhaps it’s just as well then that fate decided to slip into the mixer’s chair. Many of the song’s fans would undoubtedly disagree with Tomlin’s assessment, deeming the ‘Witchdoctor’ which ended up on the actual record as one of the finest examples of white R&B recorded anywhere in the 1960s.

Cue the live ‘Witchdoctor’ as mysterious Max Kelly rips out a frenzied tapestry of blues notes, riding wildly above Rudd’s rhythm and gut moaning “Heeeey Hey Hey ... Heeeey Hey Hey ... your witchdoctor, go witchdoctor ... I got my eye on you.” You’re right back there in that dark, low ceilinged cellar, part of that whole mid-sixties white R&B fantasy, Christchurch branch, prey to the dark seductive power of the blues and its possessed practitioners.

Chants fans later lapped ‘Witchdoctor’ up, of course, sending it to No.12 on the Playdate chart, prompting good local airplay. By then, however, the Chants were in Melbourne. After Kelly’s deportation, they were determined to join him in Australia. A band friend, Tim Piper, briefly joined on guitar, but was never considered for a permanent place in the band.

One final hitch. Martin Forrer’s parents convinced him not to go, a decision he now deeply regrets. His replacement was Neil Young, bass player with Christchurch pop band The Five Degrees. Forrer in turn joined The Five Degrees.

The End in Christchurch and to Australia

The Chants left Christchurch in November 1966 after a final chaotic appearance at 3ZB studios, surrounded by hundreds of kids outside.

Rudd: “We’d done as much as we could in Christchurch. I’d been fortunate to inherit some money when I turned 21, so moving was a real possibility.

“We left behind a large army of fans weeping at the airport. We weren’t going blind, exactly: I’d financed our roadie Tony McCarthy to investigate the Oz scene. He landed in Sydney then went down to Melbourne, which had a pretty healthy R&B scene. So we went to Melbourne."

“The city was just recovering from the peak of the mods versus sharpies wars, but there was enough conflict around for me to cut my hair before we left.”

Their mod followers saw the Chants off in fine style, nearly razing Rudd’s Cashel St rental home in the process.

Sometime support band, The Who-ish Our Generation inherited the Stage Door residency, soon changing their name to Trust and Love and adopting a more psychedelic (a la Cream) style. The venue also changed names to the Ram Jam, but it would soon close after council action over health and fire risk on the premises.

Meanwhile, in Melbourne, the Chants were shacked up in a cheesy boarding house full of the city’s musicians, riding out the culture shock and enjoying some of the illicit pleasures that had never come their way in docile Christchurch. Both Trevor and Mike experimented with speed, a favourite drug of the local music scene.

Melbourne wasn’t lacking in places to play either. Clubs such as Pinocchio’s, The Biting Eye, the Thumpin’ Tum and Graham Geddes’ barn like Catcher with its twin stages, booked the freshly arrived Kiwis. They played frequently in the suburbs. Lunch-time shows for midday groovers. Evening shows at the Catcher with The Chelsea Set, Jeff St John and the only Oz band the Chants rated as in their league, The Purple Hearts, an incendiary Aussie outfit who drew on the same R&B sources.

Then they struck a problem that hadn’t been apparent when the band was playing to Christchurch fans. They were too diverse for the more focused Australian fans.

Rudd: “When we arrived there, we found that the Chants’ biggest problem was our selection was too eclectic, too broad a range of stuff and when we struck the clubs here, the bands were very directional. We had to make a choice between the blues and Tamla and that knocked us out and sowed the seeds of dissension.”

The split in tastes was emphasised on the only Australian recordings the band made – cover versions of soul classic ‘My Girl’ and Them’s R&B shouter ‘1 2 Brown Eyes’ recorded at Chapel Street’s Clever Sound Studios and rated by the band as their best recordings yet.

The arguments over repertoire continued, but not for long: Trevor Courtney was offered the drum stool in Campact. It was too good an offer to refuse. He was replaced by Tinsley Waterhouse. Rudd then bowed out and took the opportunity to marry his Christchurch girlfriend, Helen, eventually joining Ross Wilson’s Party Machine on bass.

Kelly and Young tried to carry on, but without Rudd and Courtney the soul and spirit had gone. They soon moved off to other projects. Christchurch’s finest ever R&B band was no longer.

Mike Rudd: “We were really dedicated to our music, not drugs, not women, we genuinely loved what we were doing, but we were little lost kids floating around in a market we didn’t understand.”

Postscript

Mike Rudd went on to chart success with Party Machine, who had a minor hit with ‘You’ve All Got To Go’ in 1968, beginning a personal career, which sat just to the side of real Australian fame. He went on to release a number of fine albums with Spectrum, including Spectrum part 1 (1971), itself notable for not including the hit ‘I’ll Be Gone’, and Milesago, a double LP) released in 1972 on EMI Records. Rudd let his funkier side go in Indelible Murtceps, a side project who recorded an album Warts Up Your Nose in 1972 and shared two albums with Spectrum in 1973: Testimonial and the live Terminal Buzz.

Ariel followed Spectrum in 1973, ploughing through seven line-ups and a handful of albums, including A Strange Fantastic Dream, which spawned the hit single ‘Jamaican Farewell’ in December 1973, and Rock & Roll Scars, recorded at London’s famous Abbey Rd Studios.

Even then, some projects never saw the light of day – Rock & Roll Scars – being a last minute replacement for a rock opera that was deemed too risky at the time by EMI, Rudd’s record company.

Later he formed Mike Rudd and The Heaters who released ‘Australian Girl’ and an album on Mushroom Records. In the mid 1980s, he formed W.H.Y, which combined live stage performance with synchronized video projections.

Rudd still lives in Melbourne, concentrating on recording and playing live regularly in a version of Spectrum. He was aided by his bass player since Spectrum days, Bill Putt (late of the Lost Souls), who died of a heart attack in 2013.

Trevor Courtney soon left Campact (who recorded at least four singles) and joined a cabaret band called The Vibrants (who at one time backed Bobby James) in which he made pots of money. Skylight, a soul band, followed, releasing several 45s and an album.

Martin Forrer quit music completely in 1967, later becoming a dairy farmer in the North Island and raising a family. In 1994 he’d recently moved to Auckland with his second wife and still plays jazz bass around the city.

Matt Croke and Neil Young joined Grandma’s Tonic, who were later featured on the excellent Ugly Things compilations. Croke went on to Bay City Union with Matt Taylor then did a bit of globetrotting before resuming his electronics trade career. In 1994, he still played up to 20 hours a week.

Neil Young set up a cleaning business in Melbourne and was last heard of studying music at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

--

Read more: Christchurch Underground, 1964-69

Chris Grosz on Christchurch Underground, 1964-69

Chants R&B page on Mike Rudd’s excellent website

Elsewhere interview with Rumble and Bang film-maker Jeff Smith

Ngā Taonga page for Rumble and Bang – Chants R&B documentary

Mike Rudd - rhythm guitar, vocals, harmonica

Trevor Courtney - drums, vocals

Pete Hanson - bass

Jim Tomlin - lead guitar

Neil Young - bass

Martin Forrer - bass

Max Kelly - guitar

Tim Piper - guitar

Stan Major - saxophone

Compton Tothill - bass

Rumble and Bang, a Chants R&B documentary produced by Jeff Smith and Simon Ogston, featured at film festivals in 2011.

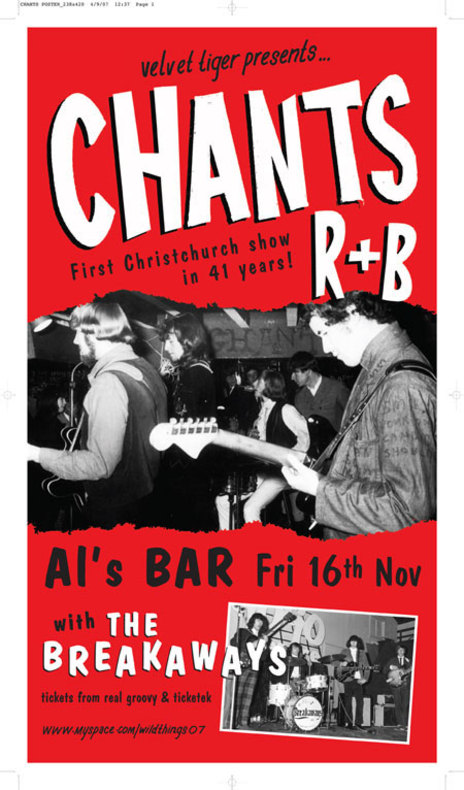

Chants R&B reunited for New Zealand shows in 2007 and 2010.

Jim Tomlin was head of Otago Polytech’s art department before retiring. In recent years, he has played jazz at Dunedin’s casino.

Mike Rudd had a No.1 Australian hit with the spacey harmonica-led I’ll Be Gone in 1971, with his underground progressive rock group Spectrum. He continues to play and record in Melbourne.

Searching for the South Island long hairs

“These, believe it or not, are men!” – The Pretty Things in New Zealand, 1965

Action!

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air