AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Steam

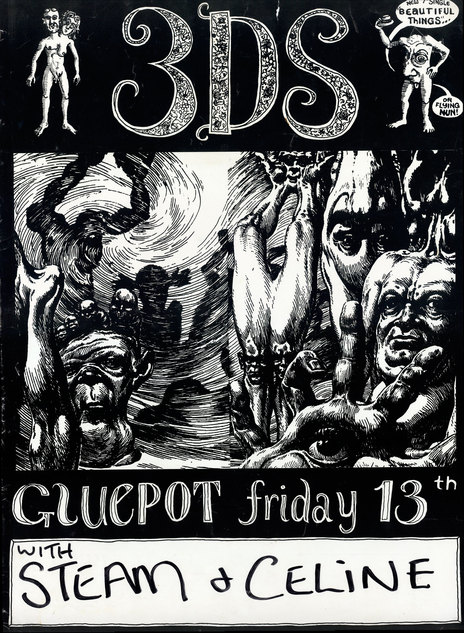

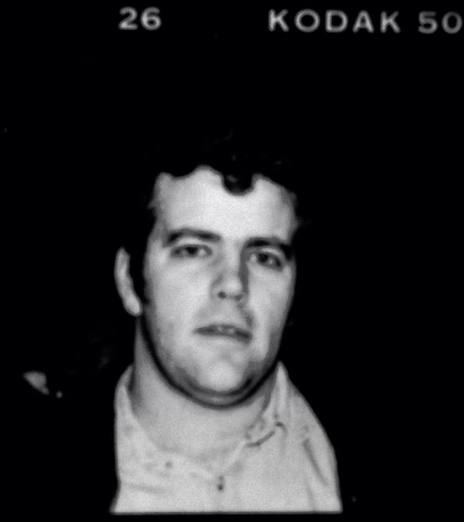

Socially connected to the musical and artistic underground and the Auckland based Flying Nun label, the highlight of Steam’s short existence was a blistering, pulsing set at the Gluepot, Auckland, playing as support for The 3Ds. But they went their separate ways after a disastrous gig that saw lead singer Chris Mckibbin disappear into the night, not to be heard from again for many years.

Steam formed in the wake of Mckibbin’s earlier musical project, Lee Harvey. Under that name he released an EP, Security 198 (1991) through Flying Nun and collaborated with members of the Hallelujah Picassos, who backed him under the name The Bagmen.

“The Lee Harvey thing was kind of burnt out really,” Mckibbin told AudioCulture in 2015. “I did a lot of groovy 4-track stuff that used to get a lot of play on bFM. The original bass player [Tony de Raad] from the Picassos headhunted me; he wanted to be in my backing band. He left the Picassos so Peter McLennan was on bass with Bobbylon on drums – they were my backing band. So it was like always playing second fiddle to the Hallelujah Picassos.”

Steam initially came together as a trio with Mckibbin, Nick Kreisler on bass and Danny Mañetto on drums.

Steam initially came together as a trio with Mckibbin, Nick Kreisler on bass and Danny Mañetto on drums. The son of Taranaki artist Tom Kreisler, Nick played bass in Greg Fleming and The Trains with guitarist John Segovia, who was the link to Mañetto, as both played in Shaft.

“It was two solid years of grind,” says Kreisler. “1992 to 1994, although we might have started in mid-1991. I was living with Chris in Ardmore Road, Herne Bay in a shared flat. I was aware of Lee Harvey and what he was doing. I’d been around to a flat he had in Grey Lynn where he was living with [Hallelujah Picassos manager] Lisa Van Der Aarde. He was really hunkered down and working hard on his music. He had a spare room kitted out with recording equipment, a guitar and amp and some other instruments. He was like a Beck character, a one-man band sole operator doing quite kooky music. But I thought he was really talented and I liked his singing voice as well so I fostered a relationship with him.”

Kreisler was hanging out around Galatos Street, a hub for band rehearsal space in the early 1990s. “I think he was rehearsing his band The Bagmen around there a bit. Chris was quite a strange character, he was quite aloof, and he wouldn’t give away much about himself so I found him quite intriguing and probably wanted to find out why he was so mysterious. He still had a relationship going with Flying Nun with the possibility that he’d do more through them. He made some tracks with a drum machine that he took to Dunedin for Orientation. I really liked a couple of the songs and I said ‘you need a band, I’ll play bass and we’ll get some other people.’ ”

As well as being a member of Shaft, Mañetto’s musical background included playing with Hamish Kilgour in The Mad Scene (formerly Monsterland) and he was the cellist behind the overdubs on Straitjacket Fits’ ‘She Speeds’ and 'Dialling A Prayer'.

“I was a fan of Shaft, going to countless gigs,” says Kreisler. “I knew Bob [Cardy/ Brannigan] and Jon Segovia, he was playing with Greg [Fleming] and I – and there was a strong Galatos connection through those guys. We started rehearsing and I thought Danny was a really great drummer. He had an offbeat sense of humour and we became good friends quite quickly, he introduced me to Big Star, he was all over stuff like the Feelies, Suicide. Before Danny, Chris and I played with Bobbylon a couple of times. It was much more dubbed out. When Danny came in it immediately became driving rock music. I remember doing a song that sounded very Pixies.”

“Danny introduced me to Can,” says Mckibbin. “Danny’s a very good drummer and all round musician, he can pick up any instrument and play well. But we didn’t sit around together as a group and overanalyse music and say ‘this is the direction we should go’. We never had any massive influences, we all listened to varied stuff but when we got together in the rehearsal room, when the night was right, it was electric.”

Steam started gigging in 1992. “We played a gig at the Dog Club [aka Dogs Bollix] that Stuart Broughton was managing,” says Kreisler. “That was our debut gig. Chris organised someone to get up and play bagpipes on one of our tracks. He just had a really good feel as a musician – a lot of it is really intuitive. I guess that’s just musical talent. When he let rip he had an incredibly powerful voice.”

Shortly after their debut, Danny announced that he “wasn’t really that good a drummer”. “He brought this guy along, it was Robert Key,” says Kreisler. “Within a few minutes it was clear that he was a really good, tight drummer.” Key already had many years’ experience as a drummer, with acts including NRA, Jay Clarkson’s They Were Expendable, The Sombretones and The Cakekitchen.

Mañetto: "Shortly after our first show I was at the Gluepot and I bumped into Rob. I’d known Rob for five or six years. I’d seen him play in Cakekitchen and in an early incarnation of Not Really Anything (NRA). I really liked Steam and I really liked playing drums. I can pass for a good drummer but I’m not someone whose timing is really good like Rob is. There are a few drummers in NZ that I think are really phenomenal, Rob is one, Alan Haig is another, and Hamish Kilgour. They’re human metronomes but they have a groove as well. I knew he’d been in and out of the country touring with [Australian Theatre group Stalker Stilt Theatre]. He said it was all finished for now. I said, 'I'm in this band, you should come and join'. He said who’s in it and what will you play? The next practice with Chris and Nick I put it to them, neither of them knew Rob Key. The following practice I took my guitar and amp along and Rob came along."

“Danny wanted to play guitar,” says Kreisler. “Chris and I didn’t know that he could. We knew he could play bass and cello. He managed to borrow a Gretsch off Tony Bones. He kept going on about how some junkies had stolen his guitar and moved to Dunedin.”

Mañetto’s approach to guitar was unconventional. “He played like a guy who was just trying to get a throb going. At times it was difficult, he was fucking loud but he was getting this amazing sonic thing going. It just sounded huge. When Robert joined and Danny went on guitar, suddenly this band had this fundamental sonic power. To me that’s what made Steam a great band. It was that thing.”

"My fingers were cello playing fingers from age eight," says Mañetto. "That classical sense of melody … if you start playing guitar you play music that’s rooted in black American music. Whereas my start in music was classical. When I do things in music there’s no blues in there – maybe a bit, I like rock and roll and learned guitar from records I really liked, but when I make stuff up … it's not intentional, it's just how my fingers work. And the throb thing, it's simplicity. From playing in Shaft I really understood that it's better if you're playing in a group with four people to keep it from being cluttered up ... my sound was basically the tone rolled down. I played through a bass amp, a Holden Graphic."

The four rehearsed in a space attached to a language school, between Auckland Museum and Parnell Road. “There was no one there in the building on weekends or after hours,” says Kreisler. “And they had a room at the back, really clean, it was beautiful, carpeted, an amazing old Auckland brick building. It also happened to be acoustically really superb. It was a good drum recording room. We did a lot of direct to 4-track cassette recordings. The drum sound was unbelievable. It helped that Robert Key was such a good drummer. We also recorded at The Lab but Chris didn’t like the vibe [of the recording], thought it was too stiff, wasn’t true enough to the sound of the band, and he refused to do any overdubbing on it.

“We liked the idea of having this huge sonic power and melding it with Can. I think that’s where Bailterspace came in, they were a sonic band, the New Zealand reference point that we could relate to.

“It got frustrating for Chris – I think he couldn’t work out where the core of the songs were. Things were moving around quite a lot. But because we were becoming such a good, intuitive improvised rock band. Chris also really loved the spontaneous stuff that was happening in the practice room.”

“Steam rolled along, laboured,” says Mckibbin. “We were just so fucking undisciplined. Our best moments, no one heard. They were in the practice room. I recorded every practice, I listened to some old tapes, it still blows me away, the stuff we were doing off the cuff. We thought we were good enough to carry that through live. There was no structure to the songs. We had ideas and we had islands to get to. Whatever happened in between happened on the night.”

Mckibbin also played a part in the early stages of Voom, the band Mañetto continued with after Steam folded.

Mckibbin also played a part in the early stages of Voom, the band Mañetto continued with after Steam folded. “When I started Steam up – I’d known Buzz [Moller] since I was 17, 18 – him and I had been jamming and doing crazy shit for years and years. We started Voom with his mate Mac [Macaskill]. Then I left or got kicked out or something like that. Always getting kicked out of bands. But I was responsible for quite a bit of the early music on the first album.”

Kreisler remembers seeing an early Voom gig that featured Danny, Buzz, Mac and Chris. "Chris and Buzz knew each other well from the kiddie show on bFM," he says. "Chris was blown away by ‘Relax’. This must have been early in the Steam chronology as well. I don’t know how it was all negotiated with Danny and Chris, how they ended up in that band but I was really angry about it.”

Mañetto says there was no crossover in Voom with Chris and himself. "Voom’s first couple of shows were Buzz and Mac, and they roped in Chris on bass and Bill Kerton on drums. The show Nick’s talking about, Pelican Bar in Elliott Street, I kinda gatecrashed the stage and asked Buzz if I could sit in on his second guitar for the last song.

"The first official play I had with Voom, after months of Buzz asking me to come to one of their Wednesday practice nights, I assumed I’d be a third guitar, fifth guy tacked onto a four-piece – but I turned up and it was only Buzz, Mac and me. Two days later Buzz contacted me and asked if i would be a permanent member of Voom. I said sure but gave up Shaft – being in three bands was going to be too much. I loved Shaft and being a backing musician to Bob’s genius and playing with John [Segovia] and Stu [Page] but Steam and Voom afforded me a bit more input. I didn’t know until the second time I had a play with Voom that Buzz and Mac had headhunted me and kicked out Chris and Bill."

According to Kreisler, Steam had a sonic attack that relied on large rooms and big rig PA systems, and it was difficult for the band to get suitable gigs. “Our first really big gig was supporting The 3Ds at the Gluepot,” he says. “The sonic thing really worked at a larger venue like that. A vocal PA wouldn’t cut it. I think that’s where things went horribly wrong at Kurtz Lounge.”

Things were about to turn pear-shaped and it would be their final show.

Having impressed the audience at the Gluepot ahead of The 3Ds (on May 13, 1994), there was a good turnout for Steam’s next gig, in August 1994 at Kurtz Lounge in Symonds Street. But things were about to turn pear-shaped and it would be their final show.

“The really strange thing with the Kurtz gig,” says Kreisler, “it was the first big gig after the Gluepot one and we had the sense that loads of people had come to see us play. There were 200-300 people there and a lot of the cool musicians from the Auckland scene – people like Shayne Carter, Gary Sullivan.”

It was a bad night. “We went on, there was no stage then, it was just on the floor. Chris was late and really out of sorts. He had slept all afternoon, and because of the acoustics of the room, we couldn’t hear anything, it sounded all scooped out. It was a wash of uncentred sound and it spooked Chris.”

“There are a lot of contributing factors that can hold a band back – bad PAs, bad room acoustics, alcohol, can all hold a band back,” says Mckibbin. “It was packed – all the wankers in the music industry, the big noters were all there. It was probably when the band could have really peaked and got some public notoriety. I was in a shitty mood, I’d been drinking tequila all day. It was just shambolic. I thought, this is bullshit, how dare we disrespect the stage like this. All these people have paid to come see us and we’re up here like a bunch of wankers thinking we’re sort of session jazz musicians and can pull this off. It wasn’t doing it for me, it was a struggle – and the whole mix, Danny’s guitar was just so fucking loud. I wasn’t enjoying it. I felt the band had come to end really. And I was just bored with music in general. I thought, that’s it – I stopped halfway through the gig, thought 'that’s not working', I packed up and walked through the crowd and out onto the street. We didn’t even meet up afterwards.”

“I remember Chris saying he’d had enough, unplugging his guitar and walking off," says Kreisler. "After that he really vanished – wouldn’t talk about it, we couldn’t get hold of him. He eventually went to Ireland; I lost touch with him for well over 10 years.”

After Steam er, dissipated, Danny Mañetto stayed with Voom, who released their debut Now I Am Me in 1998 through Antenna Recordings. Robert Key went on to play with David Kilgour and in Lanky with Jim Laing from JPS Experience, among others. Nick Kreisler founded The Pet Rocks with fellow Taranaki son Simon Sampson, later of Delta. Kreisler shifted to Australia in the late 1990s and continues to release CDs as the Pet Rocks with a changing roster of musicians. Chris Mckibbin returned to New Zealand and made his home on the Coromandel Peninsula.

Chris Mckibbin - vocals, guitar

Nick Kreisler - bass

Danny Mañetto - vocals, drums, guitar

Robert Key - drums

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air