It wasn’t until he gave up music lessons at the age of 16 – he reached Grade 6 as a pianist in the Trinity system, an experience he describes as akin to being “the world’s worst CD player” – that a passion developed. He picked up his sister’s unused guitar and found a book of guitar chords in the Mosgiel Public Library.

“I was like oh, this is all songwriting is, you pick one of six chords from a key, fiddle around until they sound right, and sing over the top of them, and you’ve got songwriting. And it was songwriting that got me. Suddenly from having no interest in music, at that moment it was all I wanted to do.”

He taught himself to play David Bowie’s greatest hits on the guitar, but it wasn’t until he got to Otago University that his songwriting took shape. He took History, winning a scholarship in his first year – and he signed up for Graeme Downes’s rock music degree course.

“Graeme was amazing. What amazes me was that he saw something in my work that, when I look back at what I was writing when I entered that course ... I remember one time him implying that I needed a bit more time, that I maybe wasn’t quite ready to like, to go out and do things right away, because actually a lot of my songs were terrible. Absolutely terrible.”

For his part, Downes recalls a young man with “songwriter smarts I guess, which is more diligence than talent, the skill-set being way wider than a mere instrumentalist. Tono was prepared to do the hard yards in any and all directions. All I can say is that he gets better at it. Life-long learning is what universities trumpet, I guess, and it is what we teach, some stuff but also how to keep learning forever.”

Tonnon wrote a lot of songs that first year – and played his first show, which was duly assessed as part of his coursework.

“It wasn’t until the third year that I said, bloody hell, my life’s started now, I’ve got to actually start playing in bands. You can’t just do this as a university assignment.”

Tonnon realised he had to start playing in bands. “You can’t just do this as a university assignment.”

He started playing solo shows at the city’s new venue, The Backstage. By the time a debut EP, 2008’s Love and Economics, was recorded at the former NZBC studio in Albany Street, with the Tweaks’ drummer Stu Harwood producing, the solo act was a band – Tono and the Finance Company. The name was inspired by the flood of TV ads for finance companies before the GFC brought it all crashing down. They played alongside the likes of the Biff Merchants, Haunted Love and Baraka and the Finish Hims.

“The thread that you hear is that there were a lot of odd, often terrible band names, and mine was especially bad.”

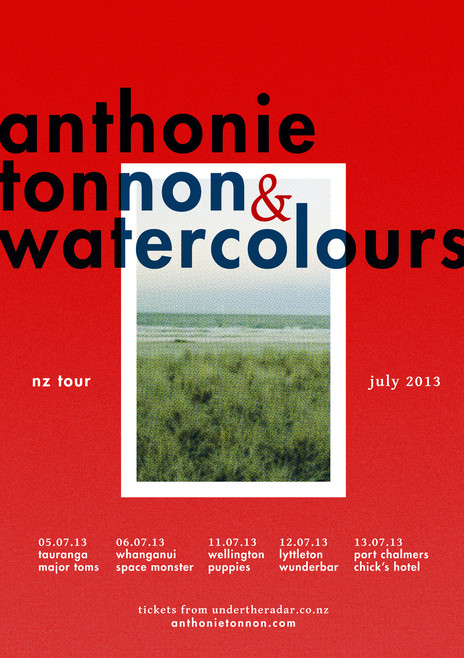

The band began to tour, a dozen dates in the South Island, then playing to small crowds in Wellington, Raglan and Auckland. It was, Tonnon discovered, hard to get noticed in Dunedin when the media were in Auckland, no matter how many sample CDs you sent to reviewers. But when Jody Lloyd, the owner of She’ll Be Right Records, released Love and Economics, new fronts opened up. Tonnon found a new community in Lyttelton, and when Lloyd moved to Melbourne, he followed him and played shows there.

“She’ll Be Right was how I first met people like Delaney Davidson, Marlon Williams and Brooke Singer, who’s now in French for Rabbits. Sometimes you feel quite impressed and proud at the size of your community. One of the great assets of being a musician is I can turn up in towns in New Zealand and all over the world and I know people, and I know where to go. That’s wonderful.”

The band recorded a second EP, Fragile Thing, in Dunedin, which included Tonnon’s first “hit”, ‘Barry Smith of Hamilton’, sung in the character of a Stars in Their Eyes aspirant. But by the time it came out in 2010, Tonnon was settled in Auckland, finding a musical community on K Road (he played in Panther and the Zoo) and friends among the Elam art crowd. His perspective on what he needed to do began to shift.

“I was exposed to Elam aesthetics, which started to heal some of the terrible, isolated aesthetics I’d been working with. We were anti-aesthetes in Dunedin. Which didn’t help us at all. We were very much, ‘it should just be about the song.’ And that wasn’t at all true. What Auckland gave me very quickly is an understanding that aesthetics were equally as much part of the art as everything else. That was all connected. You couldn’t take one side and say, ‘that’s not art that’s advertising.’ Which I guess I was very much trying to do.”

“We were anti-aesthetes in Dunedin. Which didn’t help us at all.”

He took a day job as a tour guide, which meant getting up early to ride out to Henderson and then “drive people on gruelling missions to the Coromandel”, but also branched out into music journalism with Real Groove and newsreading at 95bFM (a later dart back into journalism saw him making features for RNZ National’s Music 101). Eventually, working conditions in the tourism industry got too much and he took a job with his friend Matthew Crawley (“meeting Matthew was one of the first relationships anybody made in Auckland”) tending bar at Golden Dawn.

“He wanted to be the best drinks maker,” Crawley recalls. “So he just studied and studied and became a really great drinks maker. He’s someone who clearly does not like making things that he doesn’t like. He works really hard to become who he wants to be. Most people don’t do that.”

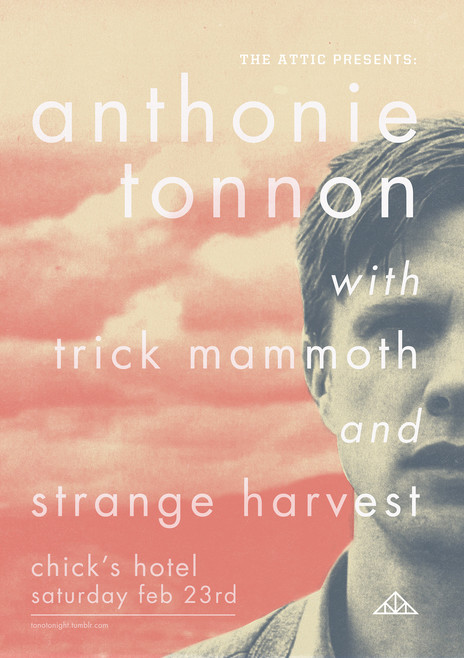

It was Crawley, ever the rainmaker, who made an introduction that would shape Tonnon’s artistic trajectory. Crawley wasn’t able to take up a gig tour-managing Artisan Guns on a South Island tour – and passed it on to Tonnon. He met Artisan Guns’ guitarist Jonathan Pearce and soon Pearce was playing guitar in the new five-piece band, allowing Tonnon to try being just the singer. He sold his guitar and amp – he needed the money – and, with typical purpose, set about learning to be a frontman.

“First gig we did, a friend of mine from Dunedin saw the gig and said, you need to get a mirror and practise what you’re doing. Which was the opposite of what a Dunedin attitude was to performing. But he was totally right. The best advice I got. So I got a mirror, and I started working out, how do you be a front person? What do you do with your crowd, what do you do with your hands, everything.”

Pearce then played on Tonnon’s first album, Up Here for Dancing, produced, like Fragile Thing, by David “Tex” Houston. It may have been recorded in Dunedin, but the album was full of the stories of a young man making his way in Auckland: imagining his future (‘Multiple Lives’, ‘Eating Biscuits’), getting drunk and getting kicked out of flats in Grey Lynn (the iconic ‘Marion Bates Realty’).

Another break came when Crawley scored the band a support slot for Beirut’s Auckland show. When the American band announced the slot, ‘Marion Bates Realty’ got 12,000 Bandcamp plays in a day, and Tonnon had his first taste of an overseas audience.

When Beirut offered a support slot, ‘Marion Bates Realty’ got 12,000 Bandcamp plays in a day.

He liked the taste, and when artist manager and promoter David Benge, then working in New York, told him that the name Tono and the Finance Company would never work in America, he bit the bullet and went out under his own name. It paid off: reunited with his guitar, he did three American tours as a solo artist, played regularly in Australia and toured Europe with Nadia Reid. His stagecraft, including the audience singalongs that are now a familiar part of his shows, developed on the road.

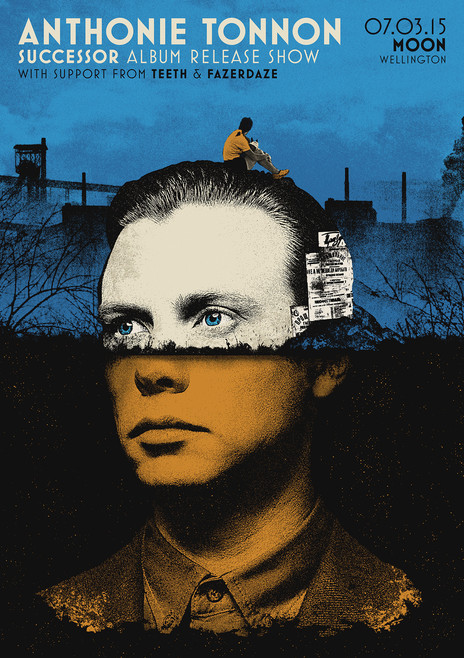

All the while, he and Pearce were working on a new album, this one crafted over time, rather than the short, sharp recording experiences that the previous records had been. That eventually became 2015’s Successor, his first record under his own name and a notable step up for his songwriting. One song, ‘Water Underground’ – which took on the unlikely topic of then-government minister Nick Smith’s interference with Environment Canterbury – was nominated for the APRA Silver Scroll Award. Tonnon plunged into the round of industry trade shows, earning himself a deal with US independent label Misra.

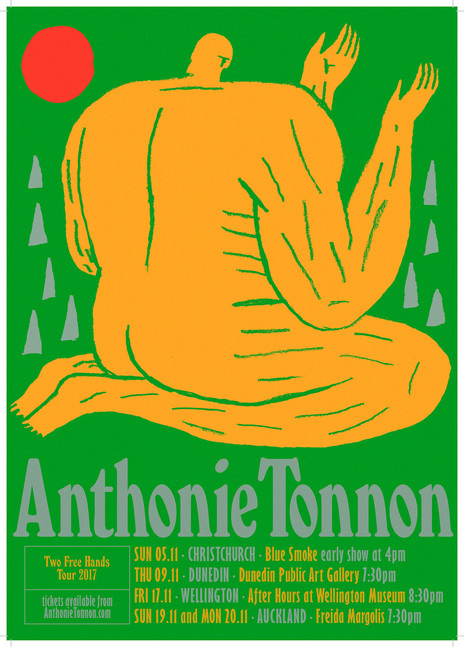

He also began working through another change on the road: a technology change. Taking a pedal-making night class with the experimental musician and composer Pat Kraus, he built a system based around an iPad, a matrix mixer stuffed into an old VHS case and repurposed guitar pedals. This let him reinvent the songs from Successor for solo performance. It was held together with Velcro and, he acknowledges, “humorously low-tech”, but let him write ‘Two Free Hands’, a new kind of song for him, built on a beat. He used the system for about 18 months before upgrading to the New Zealand-made synthesiser/sampler/sequencer the Synthstrom Deluge.

After touring Europe with Nadia Reid, and the US, Netherlands and Belgium with The Veils, Tonnon began to change the way he ran himself as a business: selling his own tickets, establishing a mailing list for fans, and often opting for small venues that weren’t traditional rock ’n’ roll spaces. It was after one of those shows, at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, that he was approached by Ian Griffin, director of the Otago Museum, with an offer to come and see the museum’s planetarium.

That in turn led to the development of A Synthesized Universe, an astronomy-themed show that let him provide “a stadium-level visual show for a folk-sized audience”. The show was picked up by the Auckland Arts Festival, attracting sellout crowds to that city’s planetarium.

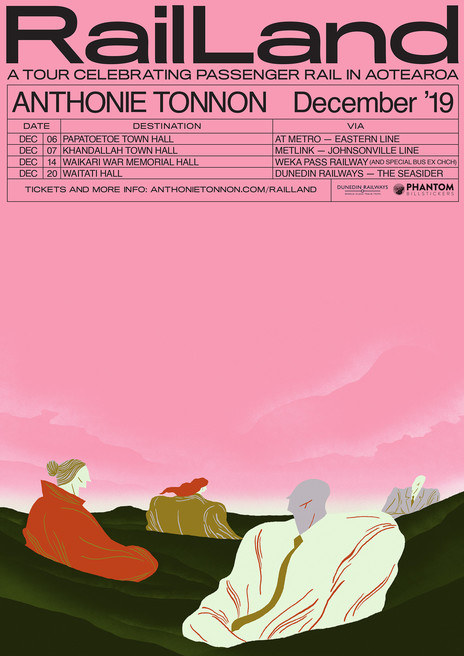

The success of the themed show led Tonnon to another, Rail Land. In a string of New Zealand centres, he based shows on a simple premise: the venue needed to be accessible by rail and patrons could buy the rail journey as part of the ticket.

Tonnon based the ‘Rail Land’ shows on a simple premise: the venues needed to be accessible by rail.

“What I realised is that I had this huge amount of power with my ability to get an amount of people to an event. I knew I could get 150 people to a gig in Dunedin, and if I could just convince them all to pay an extra $30 on their ticket, we could charter a train. And we could make a public transport train journey with a practical purpose exist, even just for a night. And that’s the power, the joy of seeing something really happen, rather than these back and forths, these long arguments that go on forever about improving public transport.”

The Rail Land shows generated an EP of new songs (plus a cover of The Chills’ ‘Submarine Bells’), 2019’s Old Images/Songs from Rail Land, and there were the ‘Two Free Hands’ and ‘Mataura Paper Mill’ singles. The last, telling the story of the environmental disaster caused by the dumping of waste from the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter in a small Southland town, was, like ‘Water Underground’, Tonnon’s version of a protest song. It would be six years between albums, but that didn’t matter to Tonnon: he was working most of the time, he had an income to live on and fans who’d turn up in every town. He looped back to RNZ to compose the music for the podcast series The Service.

Rail Land played another role for Tonnon. He had succeeded in making music his job, so public transport advocacy could become his hobby “and it was about that time that my spare time became consumed with thinking about public transport.” It led to a development which would have been bizarre for almost any other artist, but made perfect sense for Anthonie Tonnon.

After Whanganui mayor Hamish McDouall came to the 2019 Rail Land Gonville show (a chartered bus service recreated the old No.6 tram route between the city and the suburbs of Castlecliff and Gonville), Tonnon booked a meeting with the mayor. The mayor, in turn, had an offer. Since 1991, Whanganui’s public transport has been run by Horizons Regional Council – with the city permitted a single seat on the regional transport committee. But the city councillors were happy to see someone else in the role. Was Tonnon interested in being appointed as the city’s representative on the committee, based in Whanganui? Yes. He was unanimously elected to the job.

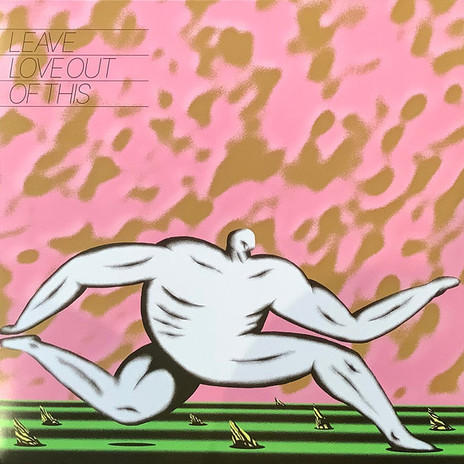

All the while, Tonnon and Pearce had been crafting his third album, Leave Love Out Of This, which gathers up the singles since Successor, along with new recordings like the title track, an epic ballad Tonnon has been playing in live shows for three or four years. On release, it will set off another studiously designed round of shows and promotions, designed not only to sell the record but keep Tonnon working and engaged with his audience, in New Zealand and abroad.

It will be another chapter in a story Anthonie Tonnon tells himself as much as he tells anyone else. The story of an artist who works to become an artist, sets his goals and, where necessary, is prepared to reinvent the whole business of being an artist along the way.

“He is constantly thinking, rethinking,” sums up Matthew Crawley, Tonnon’s old friend and mentor. “I’ve never known a more thoughtful artist when it comes to their own craft and what it means. He’s someone who doesn’t so much predict the future as decide what the future’s going be – and doesn’t accept anything else. He’s not scouring the rules, he’s busily creating his own path.”

--

In May 2022 Anthonie Tonnon’s third album, Leave Love Out Of This (2021) was awarded the Taite Music Prize.