AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Cian

aka Cian O'Donnell

Born in Hereford, England, O’Donnell’s childhood follows a similar narrative to that of many with a passion for music, though it was arriving in Wainuiomata in 1987 that would see him becoming ensconced in a life and career based on music, as well as making New Zealand his home. DJ Cian has since become the name associated with a Gilles Peterson-esque approach to bringing quality music to local ears, be it via his DJ sets and radio shows, his long-running Auckland club night The Turnaround, or from behind the counter of the many record shops he has slung discs from – the most well-known of which is probably Conch Records on Ponsonby Road.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Wainuiomata was not the place that would eventually lead O’Donnell – a traveller by nature – to seek permanent residency in New Zealand.

“I left England when I was 18, went to the States, then went to Aussie on one of those working visas and made my way all around the country. But I’d only bought a one-way ticket and my visa ran out so I had to leave, and I had fuck-all cash, and New Zealand was the cheapest and closest place to come. I had one contact in Wainuiomata and I turned up with a couple of hundred bucks. I got picked up and whisked out to Wainui, and it pissed down with rain the whole time. I was like ‘what the fuck? I’ve come to the arse end of the world!’”

O’Donnell laughs, “So I hung out there for about a week, then I caught the bus to Lower Hutt. I was wandering around Lower Hutt thinking ‘this isn’t much better’. But on the same day I caught the train to Wellington. I remember walking up Cuba Street and seeing the bucket fountain and thinking ‘this country is fucking weird!’ But later on I found a flat and I got a job in a café up on Plimmer Steps. Then the woman who had a hair salon opposite started hitting on me. I was 19, and she was in her 30s. I was like, ‘fair enough’.

Wellington sowed the seeds for O’Donnell’s now longstanding role within the New Zealand music scene.

“So she started taking me out, and she took me to Clare’s. Back then the hairdressers ruled the nightclub scene. They had their finger on the pulse musically and fashion wise. They liked drugs and they liked going out on that alternative fringe. So all the guys working with her were like my initial introduction to Wellington nightlife. It was all white electronica … New Order, Pet Shop Boys, Depeche Mode. But in amongst that was some early house and hip hop slowly being played. I found a wicked Polynesian club in the alleyway by Manners Mall and I used to go there quite a bit.”

It was not long after these initial nights out that Wellington sowed the seeds for O’Donnell’s now longstanding role within the New Zealand music scene.

“I lost the job at the café and the very same day I wandered into HMV in the BNZ building and thought ‘it’d be cool working in a record shop’, so I went on up to the counter and asked. They were looking for a part-timer in their Cuba Mall store and told me to go up there. So I went on up there and I met Matt Popplewell [a well-known early Wellington DJ] who was running the store. We ended up out the back smoking ciggies and chatting away and next thing I know he was like ‘well do you want to start on Monday?’ To be honest he opened up a myriad of possibilities for me. I ended up working there five or six days a week, but then I was also going everywhere with Matt and hanging out in the DJ booth. Clare’s, Exchequers, Alfies. And DJ wise he had this ability to mix records together that you just wouldn’t … like Laibach into Ice T into Rickie Lee Jones … he was the man!”

Though at this point O’Donnell was probably best described as a ‘keen observer’ where DJing was concerned, a combination of getting the job at HMV, meeting Popplewell, early visa-related trips in and out of New Zealand, and the influence of two Polynesian DJs would eventually lead him to playing sets of his own.

“After I met Matt I felt like I met a third of the population of Wellington in a month. And it was all the who’s who. I was treated like a king. I don’t know if it was because I had an accent [laughs]. But people offered me accommodation, took me out on the town. Coming from England where people had a front, I just thought ‘wow people in New Zealand are so hospitable.’”

Although he felt welcome in Wellington, O’Donnell was still negotiating having to periodically leave the country owing to holding tourist visas. This was occasionally a hassle, though not much of a hindrance overall for someone not yet ready to settle in one place.

Having travelled to the USA, England, Australia, and parts of South East Asia since initially arriving in New Zealand, one particular trip back to England played a crucial role in O’Donnell’s New Zealand-based trajectory. After leaving England in 1987 “just when acid house was taking off,” he returned in 1989 during the months now infamously referred to as The Second Summer of Love.

“I went to The Astoria and took my first pill and I remember walking into this one room with a black light … people had painted the palms of their hands and soles of their feet in Day-Glo paint and were dancing and thrusting their limbs out. This was around the time De La Soul had dropped ‘Say No Go’, and it was my first real taste of London in that kind of period. I hung out in England for a while, but after a while going out with mates who were necking 10 pills in a weekend, I was like ‘I’m out of here’. But that was mainly because I’d spunked all my money going on out with them!”

Thankfully not all of O’Donnell’s budget had been invested in multi-coloured combinations of the illicit Doves, Mitsubishis, and Calvin Kleins of the day, and he returned to New Zealand with music that would make him the DJ caddy du jour.

“I bought a whole lot of records when I was back there … 808 State, heaps of Transmat stuff. I bought all the big tunes I could and brought them back. I was giving them to all the DJs I knew to play in clubs … Matt [Popplewell], Clint Smiley, and so on. But I still never thought about DJing myself.”

A trip to Auckland in 1990 brought him one step closer, namely when he met Soane Filitonga. “Once again I had my records with me, even for that trip to Auckland, so once again I started meeting other DJs and giving them records to play … and one of those was Soane. He was someone I really liked, sound wise. It was 1990, and 1990 is my favourite year for club music. So I was giving him Stone Roses and all that kinda indie baggy crossover shit, and he was playing Beats International, Tom’s Diner, Soul II Soul. So I was giving Soane all these records and he was like, ‘man you should learn how to DJ’. So he was the first person who ever put me behind a mixer and showed me the basics. But I thought ‘nah I’m not cut out for it’, but at the same time I must admit I was getting more curious.”

O’Donnell had met Filitonga through Jude Campbell, who introduced him to a circle of people analogous to those he had met in Wellington.

“A bunch of them were running this magazine called Planet out of her flat … photographers, writers, DJs, performers. They then did this huge party at Wellington Town Hall. So we all took a bus back down to Wellington, which was fucking crazy. Taking the who’s who of Auckland down to party with the who’s who of Wellington. Big bottles of L&P with acid swimming around in the bottom of it. It’s all a bit hazy.”

He continues, “It was a wild party, that town hall party. I remember being on the stage tripping off my nut with Soane in front of that huge fucking organ, still handing him my records! Now I think about it I was hanging out in a lot of DJ booths.”

He was. A year or two living in Sydney followed, before O’Donnell again returned to Wellington, meeting Koa Williams not long after. “When I got back Nick Henry [Beatnick] had bought two Technics 1200s, one of the first people I knew who had them in a flat rather than a club. So I ended up taking all my records around there. He lived with this guy Dave who knew Koa, and Koa was always around there, and he saw my records and asked if he could borrow some. So I started drip-feeding him records and then one day he was like ‘man you should DJ. I’ve got a mate who’s selling two second-hand turntables and I promise if you buy them I will start getting you gigs and you’ll earn back the money you pay for the decks in no time.’ So I did, but then I realised it was more a con because then he was like ‘oh, I’ve got a room going in my house, do you want to move in with me?’ So I moved in with my turntables, so all of a sudden now he’s got decks in his house … and all my records!”

Despite his recollections of being hustled, O’Donnell is thankful for Williams’s influence. “He taught me how to DJ and sorted me out some gigs at Bar Bodega, and they went off. People were turning up to see the bands earlier and sticking around, but at the same time we were getting our own crowd on top of that as well. Then Koa went overseas but by then he’d planted the seed in me, and I was getting better and better at DJing. But … well, actually I was never very technically good at DJing, even now, but I know I play good music and I knew back then I had the tunes, only because I was moving around and I could buy records no one else had.”

The Fonky Monks were an early DJ collective in Wellington.

Now DJing regularly, by 1991 O’Donnell decided he although was committed to travelling to and living in different destinations he wanted to reside in New Zealand permanently.

“From 1991 to 1994 I was in New Zealand. I got married so I had to stay here most of the time in order to get citizenship. So that was the longest period I ever spent anywhere. And that’s when I met Matt Morel, Leon [Surynt], and then we eventually did the Fonky Monks. But before that I used to come in on three-month and six-month tourist visas, and sometimes I’d extend them if I could.”

The Fonky Monks were an early DJ collective in Wellington, synonymous with quality music across the spectrum before many dances became segregated by genre concerns. They also threw great parties.

Alongside Cian, Matt, and Leon, DJ Mu (the founder of Fat Freddy’s Drop) also formed a part of this collective. Cian first met Mu after he stole his jacket, a comical proposition if you are aware of the stature of both individuals.

“I went to a party that Dave [Anderson] and Paul Knowsley put on behind Courtenay Place and Mu had left this big quilted jacket up on this scaffolding. I didn’t know whose it was. It was the end of the night and it was cold. So about four days later I was in the Lido and this girl comes up to me and goes ‘that’s my boyfriend’s jacket’, and I was like ‘no it’s not, I bought it in England’. So she wandered off. I didn’t know it was his jacket. I didn’t even know who Mu was. But when I met him he was like ‘oh you’re that fucker that nicked my jacket’. But at that point my flatmate had nicked the jacket from me. He fitted it a lot better.”

“So I’d met Mu, then I met Leon and Matt Morel. Leon and Matt used to do this radio show called Smart Vibes on Radio Active and I’d go on up there and play records even though it was theirs. From there Leon and I started The Jewel School [radio show], and we started to do parties. The first ones were called Tone Def, at Bar Bodega, Taki Rua, and The Boatshed; we did those with an English lass named Nicky who turned on up and had really good records. Then Nicky left for England to work for Honest Jon’s and we decided to rename ourselves. We decided on The Fonky Monks, mainly because we found an image of a monkey with a phallic peeled banana. They went for a good few years up until about 1996 and then I went overseas again.”

O’Donnell then lived in San Francisco, forming an affinity with DJ Tom Thump, who he brought back to New Zealand in 1997 for a national tour, his first foray into promoting. Though the shows were delivered successfully to audiences unware of the hard work behind the scenes, the tour was colourful both in terms of a private investor with pronounced drug and ego issues (which caused particular problems at the Auckland show), and a car crash in the South Island.

“I nodded off between Dunedin and Queenstown. Which would have been fine if I wasn’t driving. I was woken up by the sound of the car hitting the gravel. Luckily Tom was awake and in the passenger seat so he grabbed the steering wheel to stop us careering into a cliff face. The whole car was concertinaed, back window smashed out, glass all through our records and the mixer. But not a single person was injured. We got to the Queenstown gig, but even now when I hit gravel in a car I have a flashback.”

The tour finished in Wellington Town Hall, and that particular gig was the last and the largest scale Fonky Monks club night.

Following the tour O’Donnell spent a month in Wellington before moving to Auckland permanently, from which the halcyon days of Auckland’s Khuja Lounge were born. “I moved because Jude [Campbell] and Gene [Jouavel] rang me on up and said we’re opening up a bar where we have been living … which became The Khuja Lounge. That place. There was nothing like it in Auckland. 1997, 1998, the first two years were when it was the place to go. Why I loved it was because at the back there was a talent agency for global indigenous actors, dancers, comedians, models, whatever … so on their books they had the most amazing looking and interesting characters, and they were the initial customers. I used to play Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday. I was the only DJ. I’d start at 8pm and finish at 4am. For a year and a half. I had crates of records, everywhere, and I’d sit down … I got grief for sitting down.”

“Khuja eventually got watered down and watered down. 1997 to 1999 though, it really set a standard. It was one of the first lounge bars I guess. And we had Janet Jackson up there, we had Kiefer Sutherland, we had Snoop Dogg. Janet Jackson and her posse came and sat fold legged around the big table. I remember she sent her homie up to the bar and they ordered Heineken and a shot of vodka in the Heineken. We were all like ‘Ooh, you’ve got no style Janet’. Then she kept hassling Tim, our doorman, for drum and bass. I remember someone raking Snoop and his homies out for a smoke, and it was the worst rolled smallest joint [laughs] and I was just going ‘oh man [laughs] you’re fucking joking’ In fact I think I walked off. I was too embarrassed. I was just like, you can’t …”

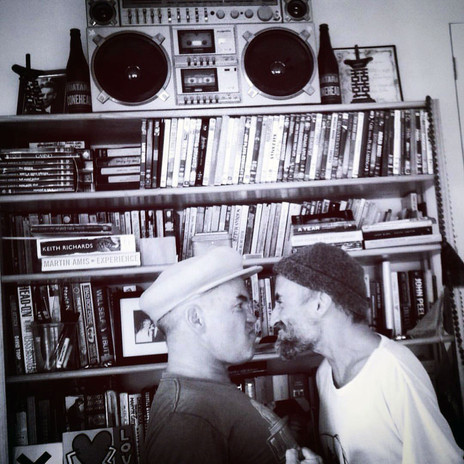

O’Donnell moved back to San Francisco again for a period, storing his records in the then-unused Galatos basement. Upon returning he evaluated the space, realising it had potential. From there The Turnaround parties were born.

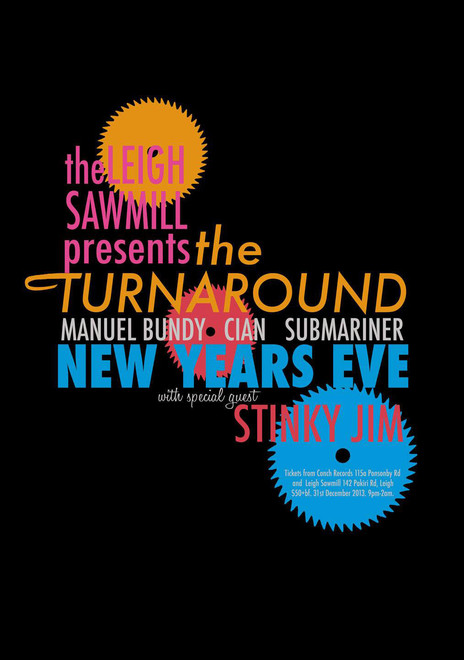

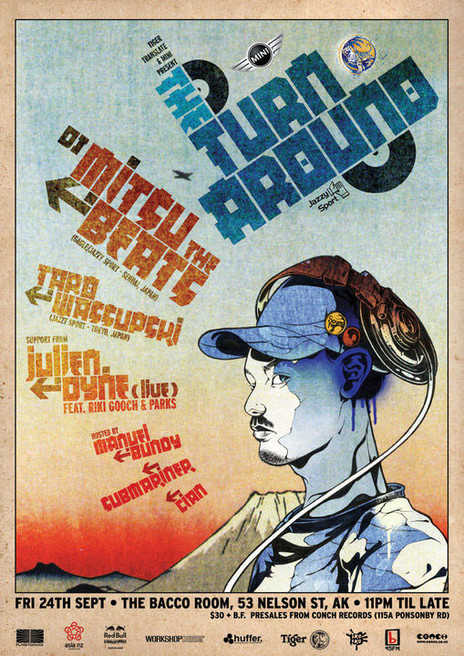

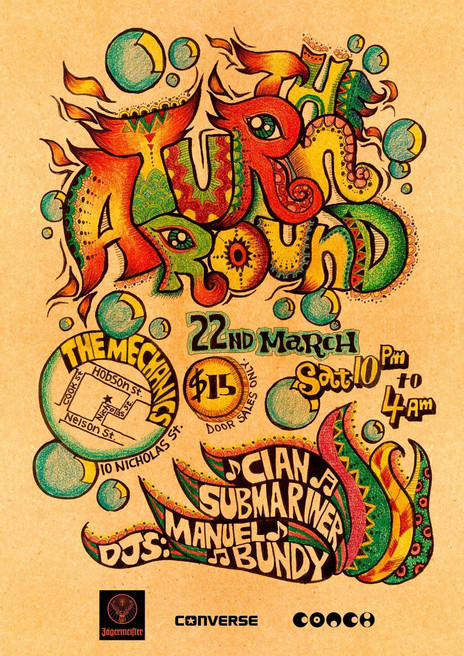

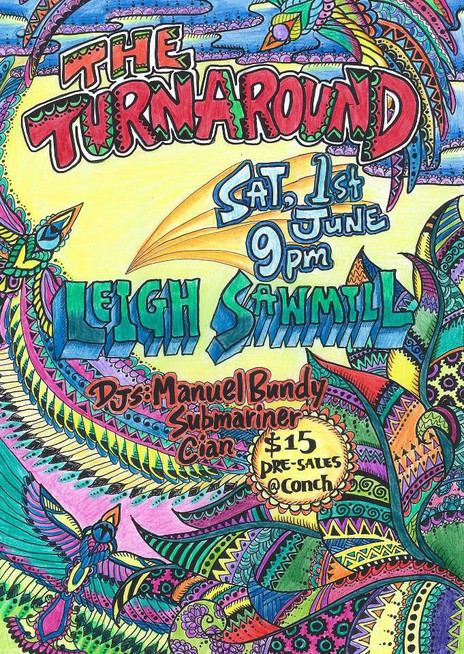

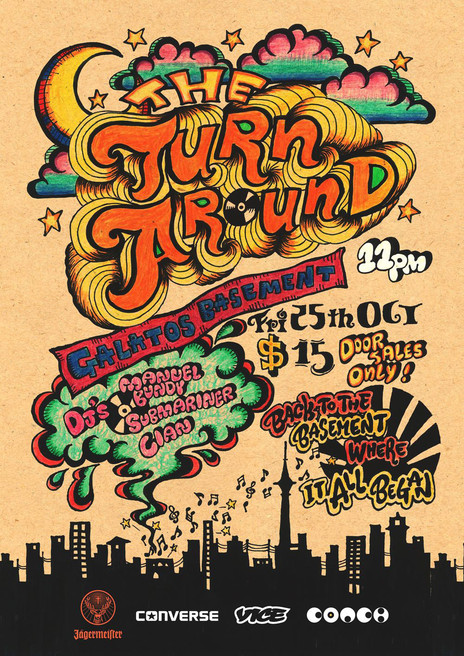

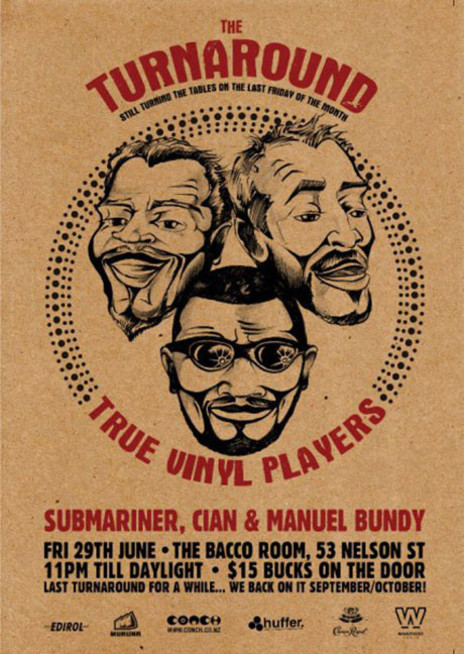

“I love basements, and I wanted to do a night there. Something about walking down off the street, usually low ceilings which equates to better sound. So I approached them to do a night down there and they were like ‘yeah man, no problem’. So I thought who do I want to do a night with, and really it was Manuel Bundy and Andy Morton [Submariner]. So we came up with a name, and I had an idea of how I wanted to promote it, like Boy’s Own, a flier that’s a leaflet that folds out with stupid shit we’d written on it. To give the scene a bit of a dig, or put top fives in there or whatever. At that time we thought Auckland needed a bit of a kick up its arse, so that’s part of the reason we called it The Turnaround. It started off as us looking at trying to fill a gap. The first one was ram-a-jammed.”

Beginning in 2002, for around a decade The Turnaround parties became a monthly fixture on Auckland’s calendar. They eventually moved from the Galatos basement space to The Rising Sun on Karangahape Road, before finally settling in at the Bacco Room on Nelson Street where the majority of parties were held.

O’Donnell reflects on the success of the events. “We had a great thing, great bar staff, great door staff … the same door staff pretty much for all the parties, and a solid bunch of helpers. And we had great people turning on up to dance too. Eventually we started getting sponsors, Heineken, Tiger Beer, Mini Cooper, Workshop, The Hemp Store, Red Bull, Huffer, Iko Iko … and that started allowing us to bring over internationals.”

Asked for personal highlights over the years, O’Donnell reflects. “At the beginning we were packing in well over 200 to 250 people every month in the Galatos basement, a venue designed for 120 peeps. From there seeing the then-new local group Electric Wire Hustle playing alongside Grooveman Spot and Kenji Sakajiri was a good vibe, as was hosting Doze Green and having him paint live at gig. Then there was Benji B playing for near on six hours and giving a grandmaster class in controlling a dance floor. I also remember Manuel [Bundy] outshining Jazzy Jay at a Turnaround up at the [Leigh] Sawmill. The Moodymann gig was great, where he ended up in The Turnaround room and kept asking about the tunes we were all playing! Also, being told by punters about all the relationships and kids that were conceived as the result of The Turnaround.”

Conch stemmed from a market stall he operated in Aotea Square in the early 2000s.

Over the years, O’Donnell continued to work in music retail until very recently, having helped set up, and then co-owned and operated Auckland’s Conch Records. Conch stemmed from a market stall he operated in Aotea Square in the early 2000s, which in turn stemmed from his privately selling music to friends.

“I was importing doubles and triples of things I wanted, and then driving around selling it to friends. I’d bring in a box of records then drive around to places like Manuel [Bundy]’s and Stinky Jim’s, and sell them records. Then Gene [Jouavel] was like ‘I’m gonna do this inner city market, do you want to do a record store there?’ So I did that, me and Sparrow, who’s an artist. He was doing T-shirts, so I asked if he wanted to go halves on hiring a stall space. Then word got out that it was the place you were gonna find shit that you couldn’t find in Truetone or Groovy or Marbecks. Eventually Benny [Staples] started helping on out most days, and we had a great thing going. Out of that whole market we were the only ones playing music, so people just gravitated to us. The stallholders loved us ’cos we set the vibe for the place. It was a really great time. That’s easily the most fun I’ve had selling records.”

Though O’Donnell still maintains part ownership of Conch, it now trades as a bar and kitchen, meaning he is taking a hiatus from selling music to people as well as operating a business on a day-to-day basis.

Reflecting on this change, O’Donnell says, “It’s only affected me in the last five years. It’s not just digital either. The location of New Zealand, so many people are used to buying stuff online. So they do that with music now too. They come in and ask for the new Moodymann tune, and I say no, but I’ll get it in an order in a month, then they go online and get it from Juno … for cheaper. Then, also, all my mates that were hardcore DJs and supported me for years, they started getting married, having kids, getting mortgages, so all those things have an effect. And Serato. People love supporting home-grown products.”

O’Donnell’s role in music retail transcends that of just a sales clerk. Like with his DJ sets and radio shows, he is well-known for passionately turning on people to quality music that they may not have otherwise heard of before, a role he does not want to relinquish anytime soon.

“I don’t want a shop. I don’t want to do it five days a week. But I’ve got an idea in the pipeline. I still want to push good music on to people. It’s my passion. It’s the one thing I’m really good at. People trust my judgement and recommendations. They know I’m not gonna push shit on them for the sake of making a sale. I’ve always got a kick out of turning people on to new music, from a young age. To me, isn’t that why we got into DJing? It’s the same thing. Music needs to be heard, you can’t be precious about music.”

Cian’s father was a professional musician, and was asked to join Manfred Mann’s Earth Band and Mott the Hoople in the 1960s.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air