New Zealand’s pop culture landscape was a messy place in the years after the tidal wave of punk surged through its city streets. Some aspiring artists tried to build a practice from the battered modes of art school formalism, while others created their own multi-disciplinary pathways. Stuart Page (or Stu Kawowski, depending on who’s asking) is a prolific throw-out-your-textbook example of the latter – a musician, photographer, music video director, award-winning documentarian, designer – and a good-natured dude.

School days

Stuart Page was born at St. George’s Hospital in Christchurch, the same hospital that Hamish Kilgour was born in a few months earlier.

“I grew up in Merivale and then my father, who was involved in carpet floorings, found a business for sale in Blenheim,” he says. “I’d been at the beautiful Paparoa Street School with its big grassy lawns and trees and a river running through, magical … and then I go to Blenheim Borough School that’s got an asphalt playground with a couple of scraggly walnut trees poking out of it. All the kids there seemed to want to fight you.

“Eventually I did meet some cool kids, because at that time the wine industry was creeping into Marlborough. They were buying up these shitty old stony paddocks for millions and suddenly we had jet boats and things on the agenda. That took care of our entertainment for the latter part of my time there”.

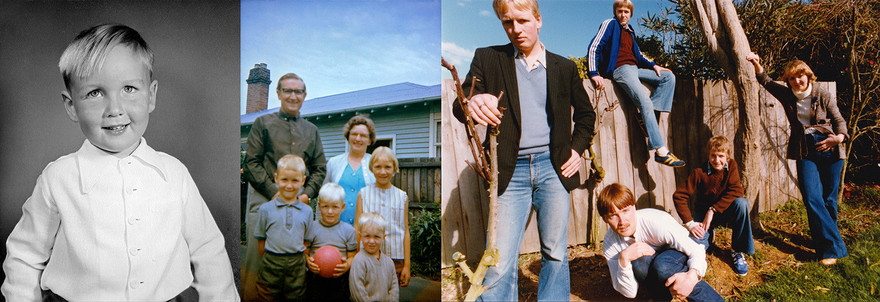

Stuart Page: Left, portrait c 1960; with his family in Christchurch not long before moving to Blenheim, January 1965; with siblings in a self portrait (from left) Alastair, Stuart, David, Martin and Suzanne, 1978. - Stuart Page Collection

Page remembers doing drawings of Fred Flintstone in his childhood. “A lot of kids did really lightweight scribbly drawings, but I used to cover the entire piece of paper with hard-worked pencil or whatever, so it’s solid colour. That was kind of my style and funnily enough I think that has followed through with my screen prints and possibly photography and filmmaking. You know, put some detail in the shadow.

“Later on, the AXEMEN had a thing about The Flintstones as well, we wrote songs about Fred and Barney. Stevie [McCabe] would get asked, what sort of music do you play? And he’d say, ‘Bedrock’.”

Page says one of his favourite television shows was The Johnny Cash Show, an alternative to the British TV shows that dominated New Zealand TV screens in the early 1970s. “It was American culture coming into the living room, and it was a really exciting contrast. When I grew up everyone was going off to England for their OE and it seemed really boring to me, I just wanted to go to New York.”

He credits one of his classmates for introducing him to David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and a world of music beyond. “There was this weirdo kid in my class who I liked called Lee ‘Zak’ Reddan, he just seemed to be really onto it. He knew that my dad had just bought this really awesome Pye Isotronic stereo, and he said, ‘Why don’t we go back to your place after school and listen to this new record I’ve got, The Rise and Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And the Spiders From Mars?’ I was 13 or 14 and I remember just standing there going holy shit! I knew that suddenly there was a whole other world out there. That was the real gateway album for me, it was like this leap into space. I soon got into Lou Reed and all that glam stuff, but Ziggy Stardust was the one.”

We pack peas

When Page started high school, he was inclined to frequent the art room. “I passed my Fine Arts Prelim in the seventh form, applied for art school and got in. I’m sorry, kids, but back then we used to get paid this lump sum three times a year, on top of which all our studies were paid for. But it wasn’t enough because you consume a lot of expensive materials at art school, so I would go back to Blenheim in the summer and work for a frozen pea company called Petersville and pack peas over the break. So yeah, we pack peas! I used to spend the whole summer working from midnight till midday seven days a week, but I made a lot of money which I needed as I was getting into photography.”

In his first year at art school – at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts, now known as Ilam School of Fine Arts – Page was drawing and painting. He credits some “really awesome tutors” there, including Doris Lusk and Don Peebles.

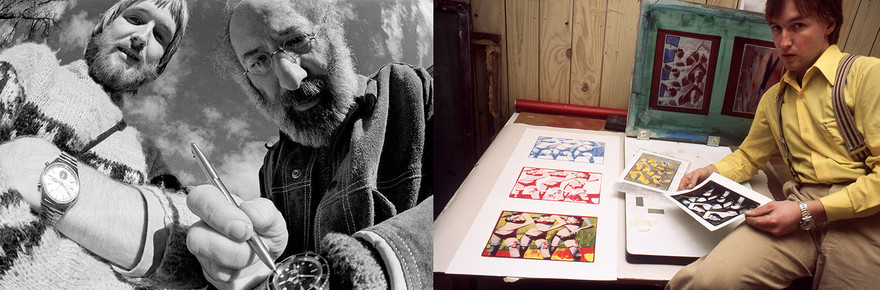

Stuart Page and Larence Shustak, Ilam School of Fine Arts 1977 - Glenn Jowitt; Stuart Page in the screen printing studio during his honours year, Ilam School of Fine Arts, 1979. - Stuart Page Collection

“Then I discovered this dude Larence Shustak from New York who was teaching photography,” says Page, “and he just seemed to be a pipeline to everything interesting that was going on. He was consuming piles of magazines every month and had books coming in and he had all these gadgets and … he just seemed to be a man of the world. We hit it off. So I changed my major from painting and drawing to photography, much to the disappointment of Doris Lusk in particular. But it’s funny because in my final year I was screen printing my photos in big pools of colour, so I mean, it was painting anyway.”

The Gladstone was our cathedral

Page studied at Ilam from 1976 to 79. The punk rock thing was happening, but not at art school. “It was still very much long hair, Neil Young and Bob Dylan,” he says. “We spent a lot of time out in the suburbs at university. Uni used to be central back in the day, but during capping the students used to go around town and vomit, so apparently the bishop put a bit of pressure on to move the campus out of town.

Tony Peake, a very cool Australian with short green hair, was running the record department in the university bookshop. “Peake was the first guy in town who looked punk,” says Page. “Tony was importing all this really cool shit, Factory Records, DAF, Swell Maps, just all kinds of post-punk stuff. He once loaned me a copy of the Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy in the UK’ 7-inch single to take to a punk party at art school where they weren’t even playing any punk, so I slapped that on and cranked it up. Tony Peake was a very important figure at that time – even Simon Grigg knew about him up in Auckland.”

Page started to see the new wave of bands at The Gladstone Hotel, attending gigs there most weekends and often mid-week as well. “The Gladstone’s Jim Wilson was the first guy to book The Clean,” he says. “Later on I saw the Skeptics there the first time they came to Christchurch, and every chance I got after that. We also saw bands like The Mockers. You had to go along and find out what you liked.

“The Skeptics were in a league of their own. No one knew who the hell they were, no one had heard of them. A Wednesday night, 10 or 20 people there, and the way they set up on the stage wasn’t your typical rock and roll gig. They had a light, centre of the stage, hanging right down low near the floor, and David was walking around swinging this bulb, which was just flying around past people. It was real Dada kind of art. And then of course there was The Gordons.”

Page describes The Gordons sound as “unbelievable piles of volume stacked up on top of each other”.

“They once used the house PA at the Gladstone as foldback and hired in truckloads of huge bins and built this big wall of speakers around the stage. That was unbelievable. I’ve heard all the bullshit about people’s ears bleeding, I don’t believe that, but it was a different experience because it wasn’t so much about the songs, just the sensation of sound. They didn’t have effects pedals or anything like that, just volume. And I used to love watching Alister Parker play because he treated the guitar like it was this sort of entity. It would hang off his neck and he’d strum it and it’d be vibrating like fuck and feeding back through the PA. He really seemed like some sort of sonic scientist.

“The Gladstone was our cathedral. There were other gigs, the Star and Garter, the Hillsborough, but the Gladstone was it.”

Local bands that Page and his peers would see around town and found inspiring included Perfect Strangers, and The And Band, the latter featuring George Henderson (formerly The Spies, they had relocated to Christchurch and changed their name).

“Mark Thomas was a Māori dude from The And Band, he was very strong-minded and quite political. He used to come over and get me to glue these little horns, about two inches long, onto his forehead, like Pan. And Bill Vosburgh from Philadelphia who had turned up at my school in Blenheim ended up as guitarist in the Perfect Strangers. Neither band were part of any scene, they’d mostly play in halls or the band rotunda, sometimes they’d play pubs, but they were definitely not pub rock. Deep, mystical songs.”

They released a split 7-inch EP titled Noli Me Tangere in the early 80s, which Page and his friend Lynton from Melbourne remastered and reissued on vinyl in 2017.

Stuart Page at far right on snare drum in Marlborough Boys' College Brass Band, Trafalgar St, Nelson (photo by Webster Page); and on drums at his Mollett Street practice room, c 1980 (photo by Kerry Willis). - Stuart Page Collection

Drums

A few years earlier, around 1974, Page saw a poster: “Wanted – drummers for school brass band”. “So I went along to an audition, they discovered that I had rhythm and that was that. My mate got the job as the bass drummer, and I got the snare drum. Every Tuesday night an Air Force guy would come in and teach me drumming rudiments. It came out of marching hundreds of people across the battlefield, so you know, left, right … so I got into the Blenheim Municipal Brass Band which had 10 snare drummers, and we’d be standing out the front of 40-odd musicians, marching girls and everything. The Marlborough rugby team had the Ranfurly Shield at the time, so every time they played, we’d go out and do a march, make a big ‘M’. I wasn’t really that into the music, but it was just great fun. I went down to the Dunedin championships and realised that the band was basically something to do when you’re not drinking.”

As Page was finishing his third year at art school he got involved in stereoscopic photography. “This guy John Perrone who was doing a psychology PhD on depth perception got me into a paid situation to help him make a 3D imaging exhibition called Project 3D. We had this big workshop. I was shooting a lot of stereoscopic Kodachrome slides with two cameras and projecting through polarising filters. Amazing stuff.”

“The exhibition toured all around the country. Perrone had been playing with Tony Peake in a band called Street Of Flowers, and they had a Pearl drum kit in Perrone’s garage. “His wife was concerned about bumping into it when she was parking the car. So he said, ‘do you want a drum set?’ And I went, ‘Fuck yeah!’”

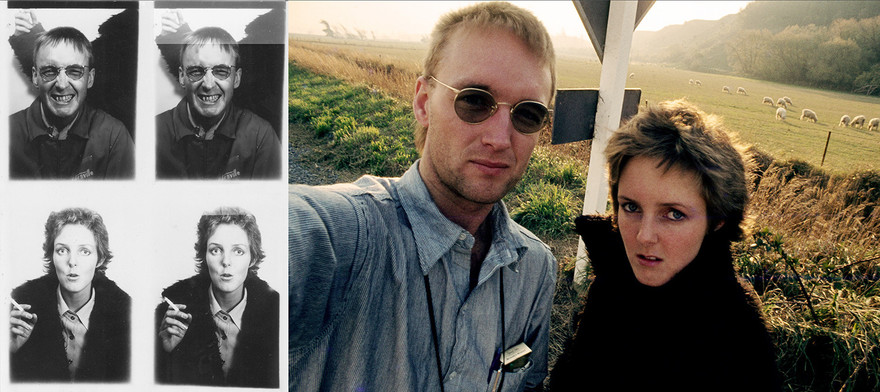

Stuart Page with Maryrose Crook née Wilkinson: photo booth snaps and in North Canterbury, both 1980. - Stuart Page Collection

Page was renting the former Mollett Street punk club premises as a screen printing studio, and he set the drums up on the old stage. “I’d work away printing then take a break and teach myself drums, sometimes I would be on them for hours,” he says. “A few punky friends of mine would wander in and bring an amp and a bass … nothing really came of it though. I just remember really loving it, the kind of groove you could get into, that special state you get into when you’re drumming.”

In 1982 Page received an Arts Council travel grant of $6000, which he says was a lot of money back then. “Enough for me to stay over there for six months … investigating American culture’s influence on my generation of New Zealanders and its differences to our parents’ culture. I attended some really amazing classes up at the Maine Photographic Workshops, and made inroads into New York, contacts and stuff.”

The exhibition of images and sound resulting from this trip was titled ‘Tripping U.S.A. – Photographs by Stuart Page’, which ran at the Manawatū Art Gallery, Christchurch’s Robert McDougall Art Gallery, and toured the country in 1985. In addition to the exhibition Page self-published 150 handmade books titled Wildside WALK, which featured screen-printed photographs and offset-printed text.

Not long after returning, Page was cycling to visit David Kilgour, who was visiting from Dunedin and staying in Sydenham. He recalled Bill Direen mentioning he’d taken over the old Sydenham Fire Station, so he popped in for a visit. They shared a drink while Direen showed him the old social room, which featured a stage equipped with a drum kit and guitar amplifier.

“We got quite trashed; I have no recollection of what we played but it was fun. Never made it to see David. A few days later my girlfriend Maryrose Wilkinson (later Maryrose Crook of The Renderers) arrived home with an Eko bass. I said, ‘What’s that for?’ And she said ‘Oh, Bill told me that I was in a band with you and him’. So, Bill basically hoodwinked us into being in this band together which I named Above Ground. Bill’s wife Carol (Woodward) also joined on keyboards.”

Stevie McCabe, Stu Kawowski and Bob Brannigan, Christchurch 1980s

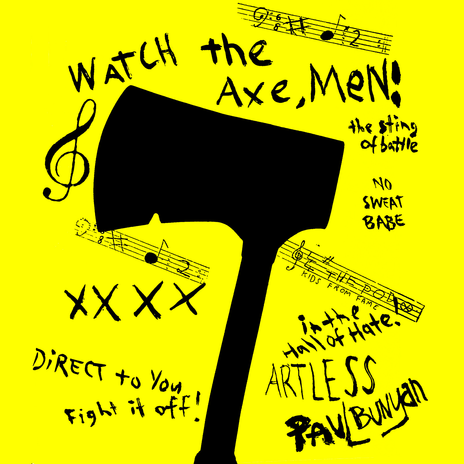

The first ever AXEMEN poster from 1983, later used as the first of two 2009 US tour T-Shirt designs

AXEMEN

Above Ground played at the Punakaiki Music Festival, and some gigs at the university and the Gladstone. “Later that year I went down to Dunedin. I had been told by a friend Zoe about an Equinox party up at George Henderson’s practice rooms on Jetty Street. She suggested I bring my congas down, so I got in my car with Christine Voice and Joanne Billesdon and we hooned off to stay at Broad Bay where Peter Gutteridge and David Kilgour had rented a house.”

The AXEMEN at Peterborough Studios, Chrischurch 1984

The friends spent most of the week receiving visitors who joined them in explorations of cactus-adjacent realms, then went into town to see some live music at The Empire Tavern.

“One of the bands was just these two young guys tuning up their guitars. I thought, oh fuck it, and jumped on the drums. It was Stevie McCabe and Bob Brannigan, and that’s how the AXEMEN were born. We did these totally outrageous versions of songs like ‘Miss You’ and ‘Love is the Drug and then all their own songs, like ‘Beware The Train Of Thought’. It was so much fun. It was great being in the band with Bill, but this was very different. Bill liked his arrangements; it had to be right. AXEMEN was improvised freedom. So then I had to break the news to Bill, which ended Above Ground and unleashed 40 years of the AXEMEN.”

Derry Legend recording session at Writhe Studio (1987), left to right: Stu Kawowski, Dragan Stojanovic, Little Stevie McCabe and Bob Brannigan

AXEMEN and Al Wright Summer 1983-84, Christchurch - Stuart Page

Though not 40 consecutive years. There was a hiatus around 1992 when Stevie’s on and off personal struggles made things untenable, during which Page and Brannigan teamed up with Danny Mañetto and John Segovia and formed a band called Shaft – but that’s a whole other decades-spanning story.

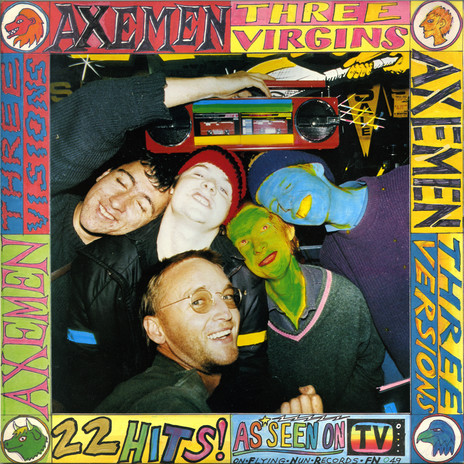

Hamish Kilgour was an avid AXEMEN fan who also occasionally mixed the band’s live sound. At his urging, Flying Nun agreed to put out the Three Virgins, Three Versions, Three Visions double LP, which had been recorded by Larence Shustak. He had brought a Teac 4-track reel to reel back from a trip to New York which he used to record the AXEMEN at the State Trinity Centre, renting the luxuriously appointed colonial environs for the Easter Weekend of 1985 at a ridiculously cheap rate (Jed Town later assisted with some mixing up in Auckland).

The finished album, packaged in a wild full-colour gatefold sleeve, was released in 1986. Along with the likes of The Fold and Fetus Productions it stands as one of the “outsider” releases that helped keep Flying Nun fresh, vital, and hard to pin down throughout this busy period.

Axemen with Stu Kawowski on the right, recording Three Virgins, State Trinity Centre, Christchurch 1985 - photo by Larence N. Shustak

Front cover of AXEMEN Three Virgins double vinyl LP (Flying Nun Records, FN 49, 1986)

Patrick Faigan wrote for AudioCulture: “The album was a mind-bending 90 minutes of catchy songs, horrible noise, catchy noise and horrible songs … a stone classic.” Alongside Sperm Bank Five/ ?Fog, Say Yes To Apes, Honey Love and numerous shorter-lived artists and collectives, AXEMEN were prolific proponents of Aotearoa’s 80s DIY culture, relentlessly recording and releasing truly independent music on vinyl and cassette (or cassette tapes stuffed into record covers that could be displayed alongside LPs). “We couldn’t wait or couldn’t afford to get anyone else to do our shit,” says Page, “so we just went for it ourselves.”

Page and the AXEMEN grabbed the DIY/ handmade baton and ran with it, making music that often challenged the indie audience but proved to be ahead of the curve. Their collectively designed, colourfully crowded screen-printed posters, stickers, graffiti, themed stage costumes and stylised photo shoots came across as cryptic and joyful, and they claim to have released New Zealand’s first hip hop tune on vinyl, ‘The Tragic Tale Of The Rock ‘N’ Roll Legend’. “Of course, it’s never been acknowledged in any books on the history of Aotearoa hip hop, but Dean Hapeta [aka Te Kupu, Upper Hutt Posse] backs me up.” says Page. “We recorded that at Writhe [the studio set up by the Skeptics] in Wellington during the Derry Legend LP sessions. Steve wrote the words and he asked me to do the rap, because after my trip to America, I was totally into rap. I turned them onto it as well, took them all along to see Beat Street at the movies. There was no resistance.”

The Great Unwashed 'Neck Of The Woods' video shoot. The curtains in the back became the covers for the ill-fated 2x7-inch release, that rendered the vinyl unplayable. L to R: Stuart Page (with Pete Gutt mask by Ronnie Van Hout), Greg Rood (dir), David Kilgour, Hamish Kilgour. TVNZ studios, the "Miss New Zealand set", 1984. - Stuart Page collection

Neck of the Woods

In 1984 The Great Unwashed (the Kilgour brothers with Peter Gutteridge) went into TVNZ to shoot a video for ‘Neck of the Woods’ with director Greg Rood, but Peter wasn’t available so Page was roped in as a stand-in wearing a Gutteridge mask fashioned by Ronnie Van Hout. “My friend William Daymond works for the Alexander Turnbull Library, and he recently sent me some scanned artwork from a Flying Nun CD compilation featuring ‘Neck of the Woods’. Handwritten in double inverted commas was a note that was cropped off, so I replied, ‘Hey can you scan that whole thing and send it to me?’ It read – ‘I wrote this song about my new friend Stuart Page.’ So I pretended to be Peter in the video, all the while and all these years later not knowing the song was about me!”

That same year saw the Auckland Art Gallery purchase and exhibit Page and Michael Shannon’s screen-printed photographs and collages from the 1981 Springbok tour protests, which remained on display in the public gallery for several years.

Great Unwashed Great Outdoors Tour screen-print poster, 1984, design and print by Stuart Page

Film/video

In 1986 Page signed up to do the film production training programme in Christchurch, but instead found himself helping founder Marilyn Hudson set it up. She then asked him to help run it. Arranging visits by industry experts such as Alun Bollinger, John Barnett and Bridget Ikin was a great way to become familiar with the film production landscape and to make contacts.

“It was a really educational year, that one,” says Page. “I discovered the 16mm wind-up Bolex camera equipment you could rent out from Alternative Cinema.”

A most serendipitous year indeed. Page shot the gleeful promo for Three Virgins on that Bolex kit, thus kicking off his lifelong film practice. Later that year he also co-directed a clip for the song ‘Brian’ by ?Fog. Along with other young filmmakers of the period, Page lucked onto a contact at TVNZ who helped him gather up 16mm reversal film short ends, unused leftovers from TVNZ News and Country Calendar shoots, a subject covered in detail by Lee Borrie in his excellent multi-part Radio With Pictures story for AudioCulture.

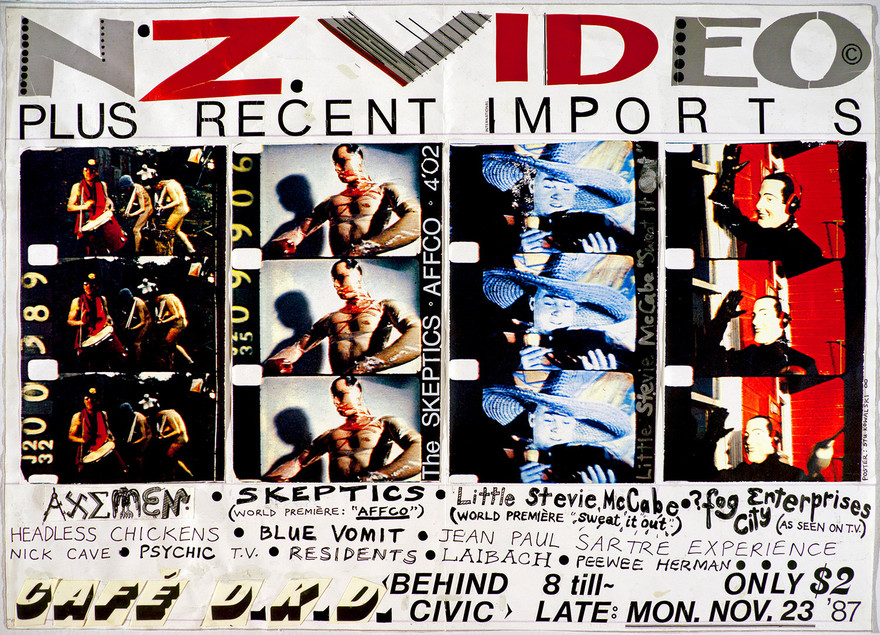

The next year he approached the Skeptics about making a video for ‘A.F.F.C.O.’, an as-yet unrecorded stand-out track from their live set. He took a boombox to one of their Gluepot gigs in Auckland to record the song and set about producing one of New Zealand’s most notorious slices of pop culture. The graphic, matter-of-fact killing floor material was shot at the Westfield Freezing Company in guerrilla film-making mode (in and out before management caught wind of their presence), while the meat packing was shot at the Kellax factory in Mt Wellington, and the footage of David D’Ath smeared in red food colouring and wrapped in cling-film was shot at Page’s flat. ‘A.F.F.C.O.’ is Aotearoa’s most notorious music video, and it was banned from play on TV (though it was aired in an act of cheeky defiance by Karyn Hay on the final episode of Radio With Pictures. It seemed New Zealand wasn’t prepared to confront the reality of industrial farming. In response to the lack of airplay, Page sold bright green VHS copies by mail order.

Poster design for NZ Video event at DKD, Auckland featuring 'AFFCO' video world première, 23 November 1987. - Stuart Page

In 1988 Page made a music video for AXEMEN’s ‘The Wharf With No Name’, a Stevie McCabe song about booze-smuggling and other nefarious goings-on down at the docks. The folksy pastiche featured the band members alongside Celia Mancini as a sultry Nazi and Patrick “Dubhead” Waller as a dodgy old salt (his character was derived from the line “the Whistling Marie”, which Page mondegreened as “the whistling marine”) and some 16mm library footage of ANZAC naval exercises. The video is a quirky entry that seems somehow at home alongside the heftier powerhouse duo of clips from this busy period: Snapper’s ‘Buddy’ and Headless Chickens’ ‘Donka’.

--

Read Stuart Page - part two here