Famously unsung in their home country, a painter, a philosopher, and a pop drummer faced their royally Rogered late-eighties reality, turned post-punk on its ear, and The Dead C with their new noise credo became one of New Zealand’s most significant and enduring musical exports.

In 2007, The Dead C’s practising non-musician Bruce Russell wrote a back page “Epiphanies” essay for “difficult music” magazine The Wire, scanning the heavy, overdue effect of The Velvet Underground on New Zealand music in the eighties: “For a good ten years, all the best music from my country started from this template and built upwards.” The Chills brought a ‘Sunday Morning’ dawn in, The Clean were ‘Waiting for the Man’, and The Dead C killed their ‘European Son’.

Influenced too by British post-punk obscurities This Heat and Flying Nun litigators The Fall, The Dead C weren’t without a New Zealand precedent. The Clean was their patient zero, and elements of their aesthetic exist in experimentalists Marie and the Atom, Skeptics and The Kiwi Animal, noisy buggers The Gordons and Shoes This High, lo-fi and DIY pioneers Tall Dwarfs and This Kind of Punishment, and a bit of the fuck-off attitude of snotty slackers The Stones.

“Funnily enough we don’t get talked about that much in the context of 80s bands. To be honest, there were a lot of pretty wild outfits in NZ back in the day, it’s just that their records are very hard to get (or they made none). But what about the Gordons, the Skeptics, Scorched Earth Policy and the Puddle? They were all whacked-out.” (Bruce Russell, This Is Your Life Now, 2013)

“We have a shared interest in music and sound. We had that before we started playing together. Discussions were about the structure of rock music, what was wrong with it from various perspectives, especially considering our context of New Zealand. Our ideas about music were to see what we could do with our restricted knowledge concerning composition and rock music and marrying this with the knowledge of audio culture that we possessed, and our interpretation of punk rock within this.” (Michael Morley, Bomb magazine, Mixtape: The Dead C, 2010)

“When we first started, y’know pretty early on, we were playing songs but then doing our best to mess with them, deconstruct them as a form of saying something about a song.” (Robbie Yeats, Live Eye TV, 2008)

Sound and visual artist Michael Morley first played around with tape recorders for school assignments. The diversion germinated, birthing first group Wreck Small Speakers On Expensive Stereos.

He traced this development to Joseph Burnett in a 2012 interview: “I started using a cassette tape machine to make sound collages, very basic sound on sound stuff, no internal inputs, just microphones and speakers and timing. In 1980 I met Richard Ram at High School, and we had a shared passion for punk rock, so we started Wreck Small Speakers On Expensive Stereos … We made cassette tapes of our sound-making, which are really rudimentary and primitive. At the time they seemed completely alien to anything that we were listening to, and our natural incompetence helped.”

Shifting to Dunedin for university, Ram and Morley ramped up WSSoES, playing out and putting out tapes, and jamming with friends and flatmates. One such collaboration, The Red Orchestra, formed when Morley met fellow Otago student Bruce Russell.

He described their meeting to Stereogum. “I had seen [Bruce Russell] around the campus and he was always at shows that were on. Bruce was a big supporter of my first band.”

Russell’s aesthetic drive was catalysed by the Morley/Ram band. He told Insample, “Wreck Small Speakers were a big inspiration to me because these guys didn't know what they were doing. They were so incompetent and they sounded so great. And I thought, ‘I’m musically incompetent so I can do that,’ and that inspired me to buy a guitar and start playing.”

Philosophy major Russell was already divining his own path through music and sound, a line he’d not stray from once he struck it, osmosing locals like The Clean and those from overseas like The Fall and Cabaret Voltaire. In a 2008 interview for Live Eye TV, he recalled his first real exposure to music, just when punk was going post.

“I didn’t grow up listening to a lot of music. I lived in a small town like Robbie and I didn’t have older brothers and sisters who were into music, and so I really only discovered music about 1977 – which wasn’t a bad time to discover rock music as it happened – but that was just by chance.”

The Red Orchestra put out a series of cassettes on Wrecked Music, Morley’s WSSOES label, and opened for Dunedin’s perennial opening act The Rip at the Empire in 1984. Russell also performed solo spoken word with guitar noise as The Coonskin Kid (sometimes with Morley as The Coonskin Kids) – though this persona was soon unseated by the sturdier sobriquet A Handful of Dust – and Morley played too with early Dunedin supergroup The Weeds. With Richard Ram and future-Bat Bob Scott, Morley and Russell were Pink Plastic Gods.

Ideas and form were coalescing, but Russell needed an OE. In 1986, he left town and lived in London for about a year, catching up with the state of live music outside of New Zealand – most notably amongst a disappointing lot, he saw Sonic Youth. Thirteen years later, in The Dead C’s first sizeable notice in influential avant music magazine The Wire, Russell described the paradigm-shifting show. “They were doing material from Evol at that point. They might have been playing recognisable songs, but everything ran together, and they were doing things that were decidedly non-rock.” Seeing Sonic Youth made concrete ideas he would soon use in his own practice.

Back in Dunedin by January 1987, he shifted into a flat out at Port Chalmers with Morley, who was playing with This Kind of Punishment, while former Garage fanzine writer Russell penned press releases and catalogue notes for Flying Nun. One afternoon, Morley suggested they form a band, with Robbie Yeats on drums.

“It was completely his idea, and I was quite surprised, since he knew precisely how little I could play conventional music, but he was quite undismayed. We had our first practice a few days later and everything fell into place. We recorded the first album inside about four months. It happened very easily because we decided to do everything the wrong way,” Russell recalled to The Road Dreamed Forever in 2007. “That meant we could dispense with things like practising, ‘honing our chops,’ all that stuff. Our entire career has been built on defeating expectations of what bands do and don’t do.”

Conversely, their new drummer Robbie Yeats was actually honing his chops in the classic line-up of Dunedin’s energetic baroque pop colossus The Verlaines, practising, performing and recording with that band from 1984 to 1990. How he ended up co-founding NZ’s major noise band with performance poet and socialist loudmouth Russell, and soft-spoken noise-weirdo Morley isn’t really that mysterious, as Morley explained to Stereogum. “It is a small town and weirdos stick out. We gravitated to the same social scene and listened to the same music.”

Yeats blissed out on his memory of the day he arrived at university to San Francisco fanzine Bananafish. “[It] was a Friday, and Wreck Small Speakers on Expensive Stereos were playing a wet lunch. I thought it was the most wonderful performance I’d seen in years and years.”

He later remembered the band in The Wire as “… mindfuckingly great. I was a Led Zeppelin type of boy, just arrived in Dunedin from Gore, and there was all this great music happening. I decided right then and there that my future was in music.”

A vigorous, instinctive drummer, the inveterate self-deprecator Yeats recalled how he slipped into the Dunedin Sound canon – and maybe why he fits so well with the irreverent Morley and Russell. “I lied my way into The Verlaines, told them I could play drums. I remember overhearing them talking about me, like, oh, he can’t keep time but he’s got some dynamic.”

Bananafish transcribed this cheery convo about that first afternoon as a trio, forever solemnised in the New Zealand Noise Diary as The Day The C Died:

“Mr. Russell: How did we get together? We got stoned and it was sunny and we probably, ah, we definitely drank beer.

Mr. Morley: We had, what, two really badly working guitar amps.

Mr. Russell: I was talking about the afternoon that you said we should form the band and we listened to Trout Mask Replica.

Mr. Yeats: I wasn’t there.

Mr. Russell: You were roped in. Michael said you would come. ‘Ah, Robbie’ll play.’

Mr. Yeats: And I thought, ‘Fuck, what a couple of weirdos…’”

With vintage Yeats winking modesty, he told The Wire, “I had never played improvised music before. I couldn’t even spell the word. It was very exciting for me.”

Their first performance was only a few weeks after that sunny beer-and-Beefheart-soaked arvo, late January 1987 at Chippendale House.

To paraphrase the lyrics of ‘Joed Out’ by his other band The Verlaines, Yeats was living his life on a knife edge, cutting his teeth with the intricately crafted and tightly composed first surge Dunedin Sound, and falling off the edge with these loosest units of the next blast wave, New Zealand Free Noise.

Their first performance was only a few weeks after that sunny beer-and-Beefheart-soaked arvo, late January 1987 at Chippendale House, the Dunedin art collective warehouse. Prompted by The Press in 2014, Russell recalled, “We played briefly and then the stage was taken over by George Henderson from The Puddle and a couple of his mates. They proceeded to play across the top of us, so we went ‘OK, that’s it, that’s our debut.’”

It’d be another year before Russell launched his influential Xpressway label (named after the Sonic Youth song ‘Expressway To Your Skull’, off Evol), but for now Russell had Diabolic Root cassettes, alongside Morley’s post-Wrecked Tapes label, Precious Metal. The first cassette from DR was a comp including Bob Cardy (of AXEMEN and later, Shaft), Alastair Galbraith, WSSoES, Bob Scott, and The Red Orchestra. The second release – DR502 – was The Dead See Perform M. Harris, the debut by the new trio of Morley, Russell, and Yeats.

An edition of 21 C30 cassettes, Max Harris (as the cassette is better known), includes two side-long practice room tracks, ‘(With Help From) Max Harris’ and ‘(Beyond Help From) Max Harris’ – a total of 28 minutes of single-chord rumbling, mumbled or barely there vocals, feedback whistles, reel-to-reel weirdness, propulsive drumming and kling-klang percussion. In effect, The Dead See (as they were briefly known) were already all there.

“Max set the pattern for our later career,” Russell explained to Paul McKessar in a 1990 Alley Oop interview, “in that we recorded the two versions of the song at our second and third practices, and released the cassette (which came in a hand printed woodcut cover w/ illustrated booklet) immediately. The 14 minutes of torture (recorded on a shitty two-track) astonished even us on playback – we’d done one track and then the other was OD’d “blind” (or rather “deaf”) without reference to the first. Truly a model for subsequent recording sessions.”

Four months later, they had an album together. “I was sort of tapping my part on a snare drum on the floor, on the carpet, sitting round on this very sunny afternoon, like a Tuesday afternoon. And that went on for about two weeks, as far as I can remember, and at the end of it they said they had an album, and I could not believe it was the truth, but it was the truth, and that’s DR503.” (Yeats, Insample, 1991)

They’d released a few of the tracks already on another Diabolic Root C30, 43 Sketch For A Poster, and were keen to release it through Flying Nun. As Russell was writing copy for them, he ran the idea past label owner Roger Shepherd – who was admittedly a bit hesitant – but Russell “just kept nagging him”.

“I remember Robbie had just got back from Australia with The Verlaines and we all went out to dinner and there was a bit of banter about the Dead C album. It had stalled at this point, and I think [Shepherd] was consciously aware that Robbie was part of one of his flagship enterprises, so if he had this vanity project with these idiots maybe he should indulge it.” (The Wire, 2013)

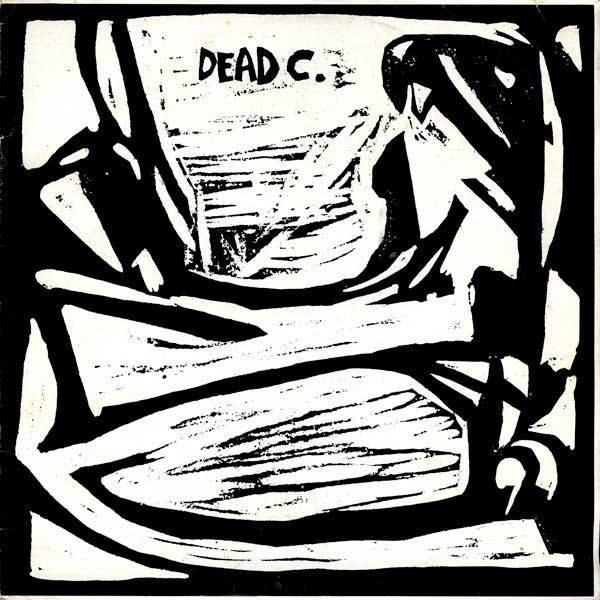

The 1988 album DR503, released via Flying Nun Records. It was reissued by Ba Da Bing! in 2008.

The album was a mix of studio and home, hi and lo-fi: 8-track, 4-track, 2-track, Walkman. Side one stumbles in with a (for the time, and even for the label) ridiculously lo-fi, urgently shambling five-minute version of ‘Max Harris’, before easing into the startling muddy-grey blues of early classic ‘Speed Kills’, then persevering as Russell narrates in rhythmic monotone on ‘The Wheel’ – one of maybe three Russell vocals in The Dead C discography – and the band scrape, rattle and drone like This Heat sniffing glue. Experimental tracks like ‘Mutterline’ and studio tomfoolery ‘Country’ aside, it’s a rock album – mind you, in the same rockery as This Kind of Punishment and Plagal Grind.

DR503 was revised and revisited in two more incarnations: as Xpressway cassette DR503b, containing alternate versions of tracks from LP and the B-side of Max Harris; and as the 1999 Flying Nun re-compilation Perform DR503c.

Russell explained to Alley Oop that “the major ‘development’ in our recording career occurred halfway thro’ the DR503 sessions when we got Richard Steele to bring his 4-track Portastudio out to Port Chalmers for some ‘field recordings’. We really loved the idea of recording at home where we could be as ‘free’ as we liked, and when we heard the DR503 vinyl and realised that the Portastudio stuff (eg ‘Speed Kills’) sounded BETTER than the 8-track, why, we were hooked. For Eusa we borrowed The Verlaines’ machine, then Michael bought his own, and we were ‘away’, as they say.”

The aesthetic set them starkly apart from Yeats’ other band, who “made a record – the last one I was involved with – that cost $200,000, and this was in the late eighties, early nineties. It wasn’t hard to see which direction was better for the way I thought about life and music and art…” (Live Eye TV, 2008). As Russell told Insample, “Our equipment is astoundingly crappy and that’s what gives us the beautiful sound that we have.”

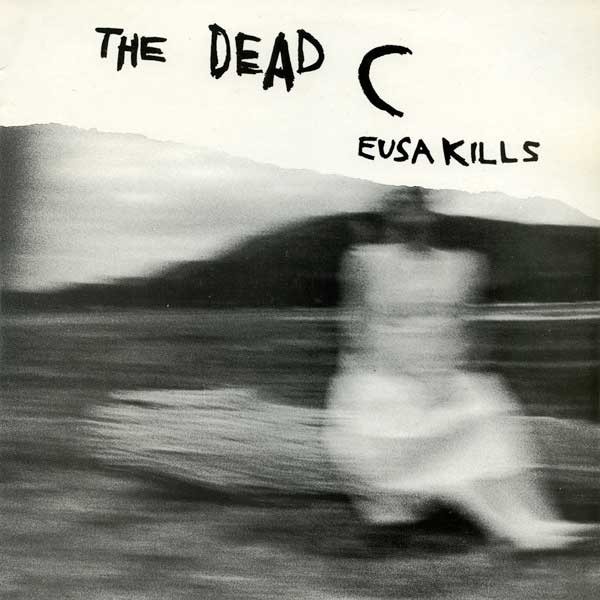

"If DR503 is “rock” then “I guess Eusa is the ‘pop’ record,” wrote Siltbreeze label head Tom Lax in the CD liner notes. “What else would you call an album w/a fuckin T REX cover [‘Children’] on it? Pretty swishy if you ask me.”

Eusa Kills, released via Flying Nun Records in 1989 and reissued by Ba Da Bing! in 2008

Eusa also marked a conceptual shift toward a more narcotic noise — slinky, unsettling bottleneck guitar on ‘Now I Fall’, agitated loops on ‘I Was Here’, pitch-shifted speed-freak vocals on ‘Maggot’.

“There’s some stuff on Eusa Kills which is pretty minimal and very quiet, sort of dreamy,” Russell told Insample, “we find it very difficult to play that live, because as soon as you start playing a quiet song everybody talks. You have to kind of rock out to keep their attention.”

And they were unashamedly heads, as Russell told de/create. “I can only think of three, or maybe four practices that we've had when we haven't been really stoned.” “No,” Morley disagreed, “I can think of one time we’ve played where we haven’t been stoned.”

A few years before this, Morley and Russell had “an ether phase,” huffing the stuff, hanging out, listening to music. “Also,” Morley told The Wire, “we would get up really early and drive out to the peninsula and collect mushrooms and eat them in April.” As their fraternal exanimates the Grateful Dead supposedly hid the words “we ate the acid” in the titles of their Aoxomoxoa album, the liner notes for the CD of Eusa Kills reproduce a Morley monoprint of the sludgily scrawled hankering “Hurry On April”.

Russell expanded on this to The Wire. “Personally, I think of us as intensely psychedelic. That’s our stock in trade within the rock traditions, 100 percent psychedelic and with everything else missing. We just stripped everything else out of rock music and kept the psychedelic element.” Don’t spark yr Nag Champa yet though, as Bruce clarified to Seattle’s The Stranger, “We don't deal principally in ‘drones’ and we don’t do ‘space rock’ either, thank you.”

--

Read The Dead C - Why use two chords when one will do? - part 2 - here