The flag that flew above The Last Resort, on Courtenay Place, Wellington. - Kerry Simpson Collection

Seldom has a name been more apt. The Last Resort really was. By the late 1970s Wellington rock venues were few and far between, bars had replaced bands with disco lights and DJs and there were few opportunities for touring groups. The capital city was down in the dumps. In 1978 The Last Resort would become the city’s only reliable rock venue with frequent gigs for both up-and-coming and name bands.

The Last Resort announces its opening night, 15 June 1978. - Kerry Simpson Collection

Yet had it not been for Lion Breweries sacking popular Wellington band Rockinghorse, it may never have happened. The band had evolved out of hit making 1960s group The Fourmyula, and, moving with the times in the mid-70s, had opted for a country-rock sound. Rockinghorse was one of our more well-known and successful bands with copious session work, two albums and a hit single, “Thru The Southern Moonlight”, under its belt.

By the late 70s the band was more or less owned by Lion Breweries, and they were a successful proposition for the kings of grog. However, a simple indiscretion lost them their gig and their pay cheque, and imperilled the group’s very survival.

The Last Resort at 21A Courtenay Place, Wellington, near the former Paramount Cinema. - Kerry Simpson Collection

Former Rockinghorse bassist Clinton Brown, whose earlier bands were Rebirth and Taylor, explains: “It happened on the day we got the RATA award for best band. We were out at Avalon [TV studios in the Hutt Valley] getting pissed on champagne with Suzi Quatro, who had presented the award – as two bass players we got on well! – and suddenly realised we had a gig to do at the Lion Tavern. And we were bad. We were terrible. At the end of the night the pub manager came up and said, ‘You guys were pretty ropey tonight’ and one of the guys in the band said, ‘We don’t need your fucking pubs, we’re the best band in the country’. And so, he put a call through to [Lion Breweries' pub circuit manager] Richard Holden who ran the show and they banned us.”

With no wages and hungry mouths to feed, the band needed a solution. They found it when they played a gig at Charley Gray’s legendary Island of Real venue in Auckland.

Last Resort - Th' Dudes play a weekend season late in 1978. - Kerry Simpson Collection

“I was most impressed with the venue and really liked it and thought Wellington could do with something like that, and that’s where the idea sort of struck,” says Brown. “And from that point I looked for some partners and found two in [real estate agent] Kerry Simpson and [musician and entrepreneur] Tim O’Connor. They took a quick trip up to Auckland to check out the Island of Real just to see what the heck I was talking about, came back and we started from scratch.”

Simpson utilised his real estate knowledge to find the perfect site: a former dressmaking factory on the first floor of a regal Edwardian building towards the bottom of Courtenay Place, which the three friends (and friends of friends) then set to converting into a proper rock venue. O’Connor, formerly drummer for seminal group The Roadrunners, “was a very practical man and an electrician and had some good tradie mates,” says Simpson, “and we needed them to convert what was a workshop for a dressmaker, or clothes manufacturer, into a nightclub.”

Aptly, the opening night launch on 15 June 1978, featured Rockinghorse, but it almost didn’t happen.

“It was all done on the trot really,” says Brown. “On the day that we opened we had a visit from the fire department and they basically said, ‘you won’t be opening tonight because you need a fire escape’. And here we are in the middle of June with a cold southerly blowing and somehow, we managed to build a fire escape on the day that we opened. We had guys welding stuff and … we got that done and I came in freezing cold and wet and changed my clothes and got onstage and played to a full house. Before we opened the doors the crowd stretched all the way down Courtenay Place and all the way round to Cambridge Terrace. It was just incredible.”

Midge Marsden's Kiwi Connection play a season at the Last Resort, June 1980. - Kerry Simpson Collection

While Rockinghorse ultimately fell apart anyway, the management trio’s reign at The Last Resort lasted more than two years and saw hundreds of top New Zealand acts play there, including Midge Marsden, Hammond Gamble, Street Talk, The Crocodiles, Rick Bryant (with Rough Justice) and Th’ Dudes. The Wednesday night jazz sessions with Colin Hemmingsen were well attended. They hosted kids’ events during the day and filmed Sharon O’Neill’s ‘Words’ video on the premises.

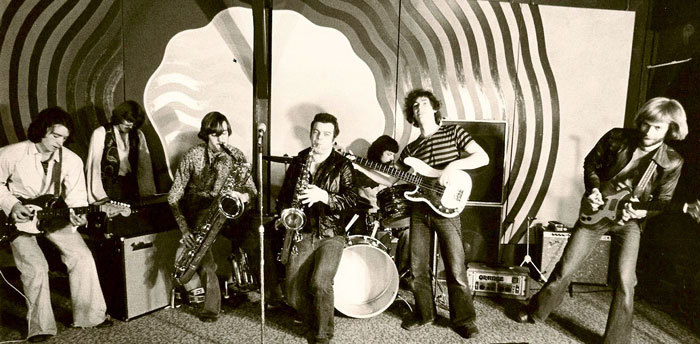

Rough Justice at Wellington's Last Resort: Stephen Jessup, Mike Gubb, Peter Boyd, Rick Bryant, Nick Bollinger and Peter Kennedy.

“We were young and rash and it seemed like the best thing to do,” says Kerry Simpson, who ended up being the hands-on manager while Clinton was away with his band or touring with Sharon O’Neill. “It cost me my marriage unfortunately, getting home at four or five in the morning and back there by 10 or 11 in the morning.

“Not being able to sell booze was always the biggest issue really. The bands got pretty much all the cover charge, and we relied on consumables, and it was never going to work, in hindsight. Two and a half years was more than enough really. Had it made money it might have been different. But we were in it for the benefit of the bands. There was no thought that we were going to get rich.”

Schtüng: four nights in February 1979 at the Last Resort. - Morton Wilson Collection

Brown concurs that the takings from the standard $5 admission and the odd coffee or carrot cake meant that the venue never made the kind of money it needed to. Brown and pals investigated getting a liquor licence but the red tape together with the huge upfront costs at that time made it impossible.

“We aimed to get a New Zealand wine and beer licence and that’s what we needed to be able to survive financially, but we had the liquor licensing guy up and we gave him a nice lunch and it was a beautiful day and the place looked great and then he went round and came back with a handwritten report saying it’s going to cost you between 10 to 12 thousand dollars to upgrade your loos, your toilets, your kitchen. And we set the whole place up for less than that! And even then, there was no guarantee that you’d get a licence.”

Last Resort poster for Shotgun, fronted by Larry Morris. - Kerry Simpson Collection

Brown looks back at his two years at the helm of The Last Resort with great affection, even though it became untenable. “It was fantastic. I had lots of friends in the bands that played there and it was great to see them play, have a good time and pay them some okay sort of money at the end of the night.”

Lip Service, Last Resort, September 1978. - Kerry Simpson Collection

It got harder rather than easier by the turn of the decade. “We’d had such a good time but it was a struggle getting bands, a constant struggle. It was really hard to fill up the weekend nights, Thursday to Sunday.

“About that time a lot of the big bands like Street Talk were either moving onto greater things or breaking up. It did make it tough. They all sort of wound down really. And then of course the Rock Theatre opened and they thought we were doing such a wonderful thing they’d have us on. They had a much bigger venue and they could outbid us at times.

“But we had a table tennis table out the back and that became a real thing for the musicians. Sometimes there were more people out the back playing and partying down than there were out the front. It became a real point of interest. Very competitive, too, it was!”

Johnny and the Hookers, Last Resort, July 1979. - Kerry Simpson Collection

On top of it all The Last Resort had arrived on the cusp of the punk rock era, which brought a new generation of bands and a much pricklier patronage to the venue. It was famed for its relaxed ambience and a floor full of cushions for the long hairs to zone out and listen to the bands, but the fans of groups like The Steroids, The Mockers and Toy Love wanted to stand, or even pogo.

Toy Love plays four consecutive nights at the Last Resort, February 1980. - Kerry Simpson Collection

“Toward the end when the punk thing sort of took off, that was a nightmare,” says Brown. “I remember being there one night running the place when Kerry was away. I can’t remember the band, but we’d had a warning from some punk in Wellington that there was a couple of carloads of Auckland punks coming down and they were hellbent on destroying the place, and they did. They arrived and the first guy through the door, he grabbed the cream bowl and started throwing cream over everyone. It was just chaos. People cutting themselves with knives … And that was the start of the end really, I just didn’t want to be there. It was pretty horrible.”

Bamboo at the Last Resort (L-R): Lou Rawnsley, Grant O'Connor, Steve Garden, Wayne Baird, Hamin Derus. - Wayne Baird Collection

Simpson says that it was a band from Christchurch – nobody can remember which one – that finally drove the nail into the coffin for him. “Everything had changed. The bands had changed, the music had changed, and it was much harder to get those really good drawcards. And at the end the Christchurch boot boys just wrecked it … smashed all the walls and both bathrooms. They’d gone round the town and plastered their posters over everyone else’s, and I’d given them a bit of a talking to: ‘You don’t come into Wellington and do that, there’s always space for your posters, just don’t stuff it up for other people.’ And by opening time it was obvious that they’d stirred some shit and I wasn’t a popular boy. And a really neat guy who had been my minder and had the karate school, he rang up six of his mates and they patrolled the place all night. It was going off, I mean the place was busy, but the boot boys were in the bathroom smashing the walls and the urinals. So that brought it to an end for me.”

Brown went on the road, playing bass on a long tour with Sharon O’Neill in Australia. During the tour, the three owners of The Last Resort agreed that it was time to move on.

Ambitious Vegetables, Last Resort, 1979 (Andrew Fagan at right).

The Mockers at The Last Resort, 1980 (Andrew Fagan at right) - Courtesy of The Ambitious Vegetables

This ushered in a brief second era under the ownership of Sue Barlow, a young punk fan who worked for the nascent computer industry (Datacom) but whose contact with local bands brought her inevitably into The Last Resort’s orbit.

Already a Last Resort regular, Barlow was in with a grin. “When the Resort was falling over, when Clinton and Kerry were talking about getting rid of it, I just had this crazy idea that I could do it,” she says. “Clinton and Kerry were going to close it down and the option was to either take it on and run it or let it close down. And that was basically why I did it. It was the first business I’d ever had anything to do with and yeah, it was a huge learning curve. You really don’t know what you don’t know, and at that age you’re just impervious. And everyone in town knew everyone, so there was a big network.”

The Mockers at The Last Resort, 1980/81 - Courtesy of The Ambitious Vegetables

The Sue Barlow iteration of The Last Resort was fun but fraught with misadventure from the start. “Initially I had a partner but I found out he was thieving from the door, so he got kicked out of Wellington,” she says.

There was a lot of fun to be had but the venue was never on a sound financial footing and, like the previous owners, Barlow found that its lack of a liquor licence inhibited the ability to earn enough for long term viability.

The Rodents at The Last Resort, Wellington, June 1980. From left: John Niland (Rhodes, organ), Dave Armstrong (trumpet), Chris Green and Andrew Clouston (saxophones), Peter Marshall (vocals) - Tim Robinson Collection

Barlow backs up Brown’s contention that there was a dearth of bands who could draw a crowd at the time.

“Everyone went overseas. All the straight rock and roll bands either broke up or went overseas. And it was sort of like at the end of Th’ Dudes and Hello Sailor era. It was really difficult to get popular bands because they just did not exist. A lot of the punk bands were really good, like the Blams and The Newmatics. There were a lot of really good bands, but they had a reputation, or their audience did.”

Madam Rouge, Last Resort, 1980. - Kerry Simpson Collection

Barlow was left with up-and-coming punk and new wave bands, many of whom were excellent but not huge drawcards. Had she kept it going after Flying Nun became a thing in 1981 and a larger audience was established for punk-influenced acts, then who knows? But like so many of the Wellington bands she featured, they fell through the cracks.

“It was just that period,” says Barlow. “The bands hadn’t broken into the mainstream, they were marginal, and really, they weren’t playing marginal music. Also, it was a sign of the times. Kids who dressed differently were really separated from the rest of society and really looked down on.”

Pop Mechanix start a week in Wellington at Willy's Wine Bar and finish it down the road that The Last Resort, April 1980. - Kerry Simpson Collection

Still, some legendary groups performed there during her brief time at the controls, including The Mockers (who Barlow describes as the Last Resort house band), The Steroids, The Gordons (“Brent and John are still very close friends of mine”), Riot 111, Naked Spots Dance, The Wallsockets and Shoes This High.

But it was an oppressive time for the spiky-haired contingent, who were frequently hassled by an overzealous police force and found themselves targeted by different social groups.

Condemned Sector, Last Resort, 1980.

And just to complicate things, there were the infamous Wellington boot boys adding a hint of violence to many of the gigs. I remember at one gig watching in horror as a boot got hold of a microphone stand while a band member was singing and smacked him in the mouth. There was blood. But most of the time they were simply boisterous, and Barlow is proud to note that many of them are still friends of hers who have “grown into really decent, first-class people.”

“It was a tough business,” she says. “Making the rent each week was hard, and it was a lot of hours. You had all the night work with the club and during the day you had all the cleaning and organisation and bookings and advertising and publicity. But I was lucky, I had a lot of support from Charley Gray in Auckland who was one of the big booking agents, and Benny Levin. I guess I was young and naïve and stuff but I wasn’t incompetent, and so they gave me a lot of support and booked bands through me, which they could have taken to the Terminus or elsewhere or just missed Wellington.”

Shoes This High and Toy Love at The Last Resort, 9 February 1980.

One of the more intriguing acts was Australian outfit The Reels, who performed their quirky, bouncy and somewhat ironic pop songs with the aid of cutting-edge headset microphones and small Bose loudspeakers on stands. Barlow titters when I relate how their lead singer – whose father was a Queensland politician at the time – was arrested in Hamilton later on the same tour for smoking marijuana in the back of their touring van.

When I ask her about the days and hours of business, Barlow relates the following story: “It was usually Thursday to Sunday but sometimes we did Wednesday nights as well, and either Thursdays or Sundays ended up being reggae nights, because there was a big issue between the punks and the Rastas in Courtenay Place. There were fights and running battles and stuff like that. The Rastas would wait for the punks outside The Last Resort and beat them up. I did a deal with the dude who was the head of Black Power where we’d put on reggae gigs and get all the BPs without patches down at the club, and the punks would come along because they loved reggae as well, and after about the first three gigs which were a standoff because everyone had to behave themselves, they all realised that they weren’t so bloody different and they actually all liked the same music and had the same reasons for liking it. And the fighting stopped and everyone started getting on and that was a huge relief!”

Barlow decided to take down a wall to open up the space and get rid of the by-now smelly cushions, which had the taint of hippie. “You could fit maybe 200 people in there after taking the wall down and moving the stage.”

Unfortunately, the changes deprived The Last Resort of some of its charm and turned it into a somewhat austere space.

The tipping point, says Barlow, came when the premises were robbed in May 1981. “The takings for a weekend went, and in a business that’s precarious. That made it very difficult to recover. It was a great shame.”

Still, Barlow thinks fondly of the former venue and the friends she made there, as does Simpson, who’s got a tribute to The Last Resort set up in his garage: half a dozen signs and posters and the flag that flew on the mast at the top of the building 44 years ago.

Last Resort advertisement, Rip It Up, Issue 23, June 1979 - Papers Past

Below: The video for Sharon O'Neill's 'Words', filmed at the Last Resort in 1980. In the band are Wayne Mason (keyboards), Simon Morris and Brent Thomas (guitars), Clinton Brown (bass), and Steve Garden (drums).