Few bands could re-bore ‘What’cha Gonna Do About It’ better than the Rebels with Larry out front, strutting, preening, riding the snotty words for all they’re worth as the defiant howl of John Williams’ feedback dipped from one speaker to the other and sonic mayhem broke out. At the other end of the pop spectrum, you’d be hard pressed to find a more poised ballad than the self-penned ‘Dreamtime’.

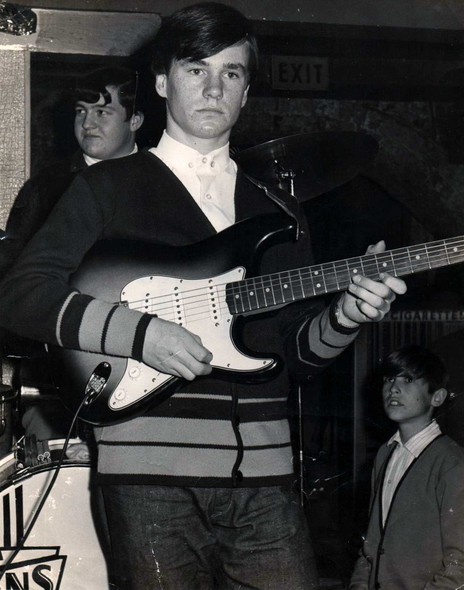

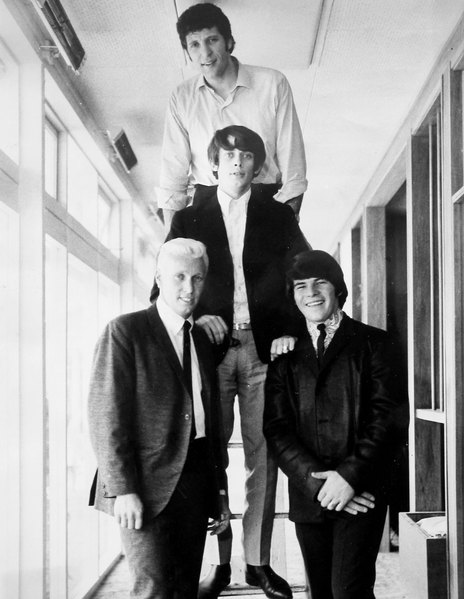

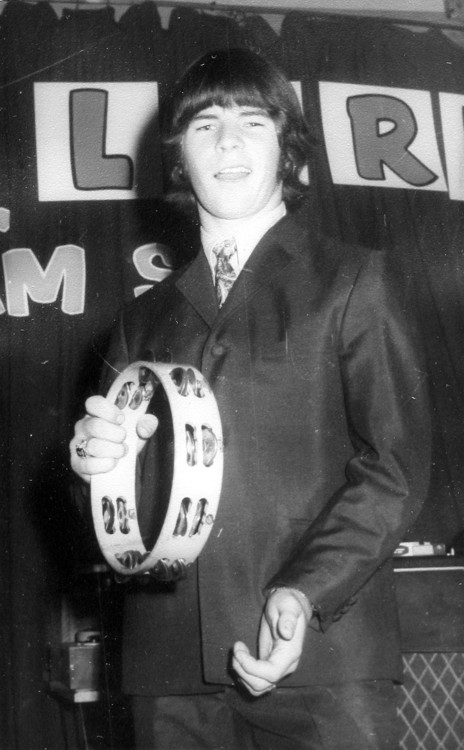

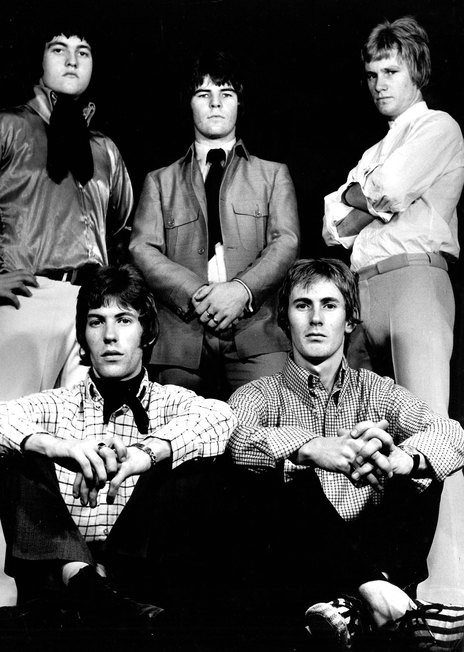

Larry’s Rebels’ guitarist John Williams was 12 — a Ponsonby boy born in Pompallier Terrace who was attending the then notorious Seddon Tech — when he first played out in 1962 as lead guitarist in Auckland instrumental combo the Young Ones. Over the next eight years he developed into a genius pop guitarist.

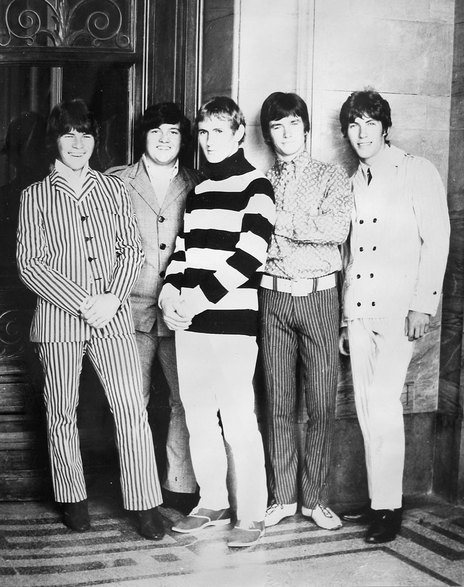

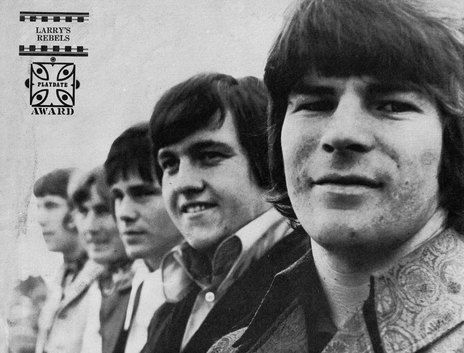

With childhood friend Dennis “Nooky” Stott banging drums, Terry Rouse on organ, and a string of passing bassists, the Young Ones played a set of Shadows and Bill Black Combo instrumentals in Auckland’s inner city halls and clubs. The Beatles’ ascent prompted a move in sound and style, and the addition of singer Larry Morris.

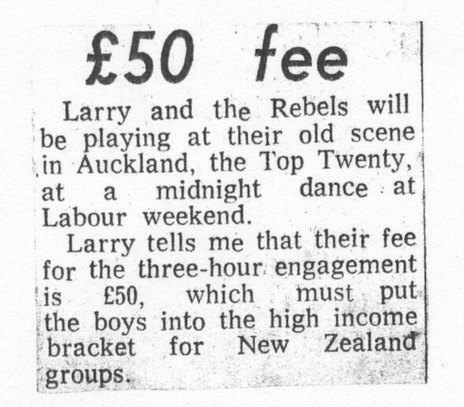

The young beat group wrangled a slot at top inner city teen club, the Top 20, through the good graces of Christchurch rocker Max Merritt. Not everyone was pleased. Larry’s Rebels clashed with another group of Christchurch imports — Ray Columbus and the Invaders. It was the beginning of a major rivalry between two hot young bands with extrovert singers and young whizz kid guitarists.

The Rebels replaced Ray Columbus and the Invaders as resident group at the Top 20, playing the pop chart hits and learning the ropes as a working band.

“THE SONGS ALL HAD TO BE DANCEABLE. YOU COULDN’T DO ANY SLOW ONES.”

— JOHN WILLIAMS

“You were allowed a two songs-on-the-jukebox break,” John Williams recalls. “And you had to play five or six brand new songs that were in the Top 20 [charts] that week or you were fined. If you were five minutes late you were fined. The songs all had to be danceable. You couldn’t do any slow ones.

“The club was open from 7.30pm to midnight. You did Friday night, Saturday night and the Sunday Club. I got paid thirty pounds. Good money. After six months I had a new Triumph Herald. Some people in my street thought I was a millionaire with my three Stratocasters and Vox and Fender amps.”

In August 1965, Auckland’s Rebels met the real thing when notorious London R&B outfit The Pretty Things played the Top 20 at the tail end of their outrageous national tour.

“They were dirty,” says Williams, “I thought they were a bunch of animals. I’d never seen uncouth, uncut people like that. Drugs. Swilling grog down. I’d never seen anything like that. We were only boys, and there were these ... It was unbelievable. Viv Prince, it wasn’t like he was human. He was just like an animal. I didn’t like them as a band — it wasn’t my cup of tea — but they were an eye opener at the time.”

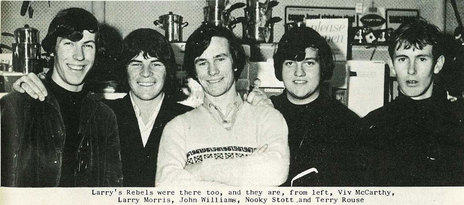

The prime exposure soon had managers sniffing around. Bob Handlin of Kingsway Productions, a “two bob shifty,” says Williams, began managing the group, which now included Viv McCarthy (son of sports commentator Winston) on bass. After a long residency at the Top 20, Larry’s Rebels shifted to the Platterack. Breaks were now four songs long.

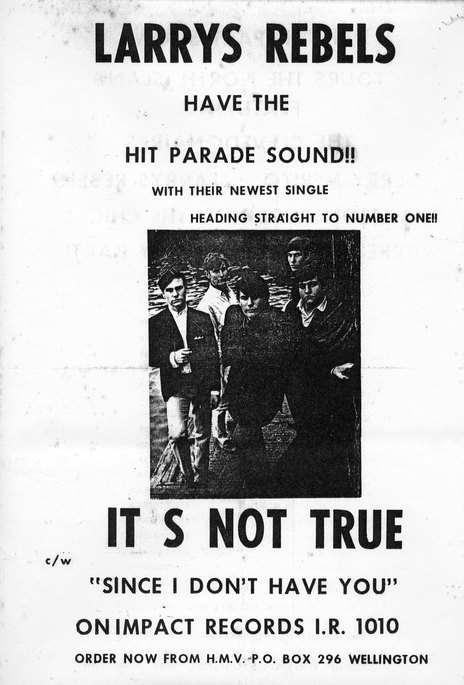

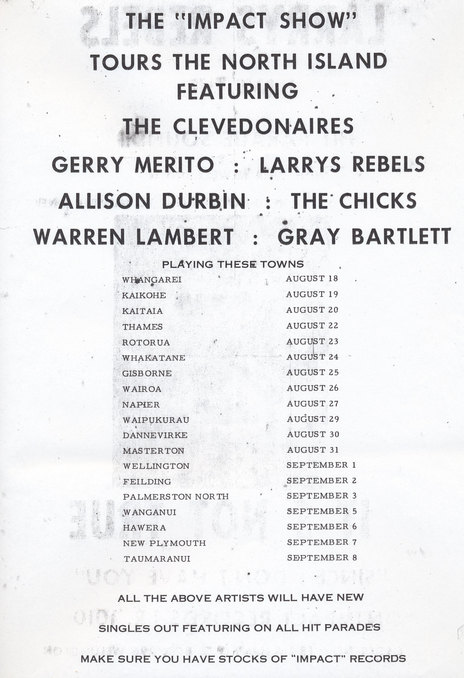

Ambitious as ever, the Rebels signed a new contract with Russell Clark and Benny Levin at Impact Promotions. New manager Clark was a savvy young Dunedinite, who also managed Ray Columbus and the Invaders, Bunny Walters, and Craig Scott.

“Once we signed that contract with Russell Clark, we were on the road,” says Williams. “That was it. Full time working. It was a very professional, integrated agency.”

Their debut single, ‘This Empty Place’, released in December 1965 and licensed to Philips, found Larry struggling on the deep notes while the group excelled behind him. The single sold respectably, prompting a successor in the Singing Nun’s ‘Could This Be Love?’ backed with ‘Long Ago, Far Away’. Both safe, folky pop moves.

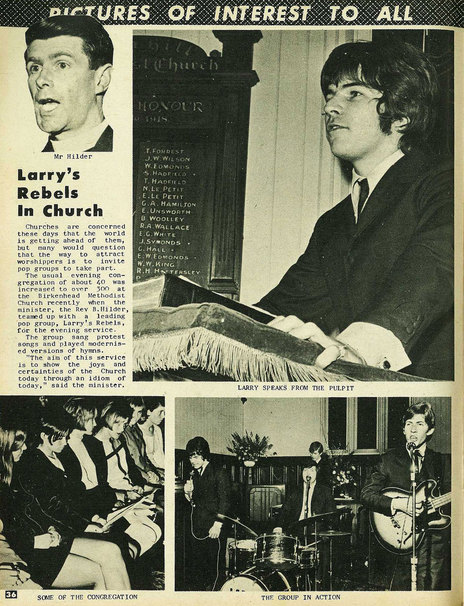

In early 1966 Clark and Levin formed independent label Impact Records to release their charge’s records. Larry’s Rebels were eyeing the charts again with another big pop ballad — ‘My Prayer’, a Tom Jones song. They met the studly Welshman when he toured New Zealand with his fine backup band, the Squires and Herman’s Hermits, mid-year.

John Williams. “We’d open the show and back the other artists. Tom Jones did ‘My Prayer’ on his third album. He did it as part of his show. He was quite advanced with the songs he was doing. There was a lot of growth and age in them.”

On their next single, a crisp, clean and powerful version of Pete Townshend’s Who original ‘It’s Not True’, Larry’s Rebels, the group, emerged for the first real time. Larry treaded solid teen turf, sneering and protesting his innocence to a jaunty early British R&B rhythm. That spunk and spark pushed ‘It’s Not True’ into the New Zealand Top 10 in September 1966.

At year’s end the Rebels played the successful Impact Christmas Tour, following up in January 1967 as support on a national tour with the Yardbirds, the Walker Brothers and Roy Orbison. The Yardbirds drew young John Williams’ eye and ear.

“We liked their stuff and we wanted to change, so we started experimenting. I got on well with Jimmy Page of The Yardbirds and played guitar on three songs in Hamilton from the side of the stage, because Jimmy would fall over drunk.”

In the tour bus, jamming, Page gave Williams the chords to his version of The Rock And Roll Trio’s ‘Train Kept A-Rolling’, which would turn up on Larry’s Rebels’ first album, A Study In Black, as ‘The Flying Scotsman’. Its restless blues clatter and lonely howl harp banged on down the main trunk line. The song’s centrepiece — a soaring psychedelic guitar rave-up — has lessons in feedback and discord learnt from touring with master guitarist Page.

There’s a lot of that mayhem in the Rebels’ third single — a manic version of the Artwoods’ loose-limbed, organ-driven ‘I Feel Good’ (written by Allen Toussaint). On the flipside all hell breaks loose on their rave-up of the Small Faces’ ‘What’cha Gonna Do About It’.

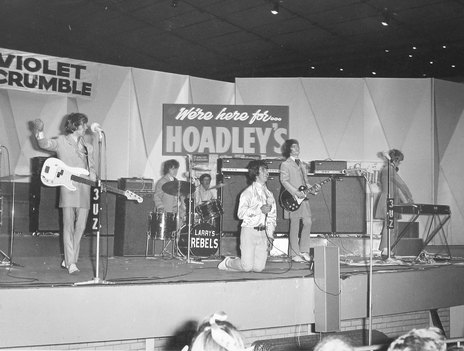

In April 1967, Eric Burdon and the New Animals, Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, and Paul and Barry Ryan toured the Shaky Isles with Larry’s Rebels in support. When the tour hopped the Tasman so did Larry’s Rebels. Promoter Ron Blackmore, head of Ambo, the biggest booking agency in Melbourne, had checked them out in Auckland and came away enthused. Larry’s Rebels stayed put in Australia to follow up their initial Australian exposure with a slot on the high profile Easybeats homecoming tour.

Back in New Zealand, Larry’s Rebels’ version of mod act The Creation’s ‘Painter Man’ hit No.6 on the New Zealand charts, staying there for eight weeks.

THE SONG BECAME EMBROILED IN CONTROVERSY WHEN A LISTENER COMPLAINED ABOUT THE INCLUSION OF THE TERM “SHIT-CANS” IN THE WORDS.

The song, like most of the Rebels’ singles chosen by Russell Clark, became embroiled in controversy and was banned from NZBC airwaves after a listener complained about the inclusion of the term “shit-cans” in the words. It turned out that Larry had recorded his vocal twice, and the phrase “shit-cans” was the result of “tin can” being dubbed twice to strengthen vocals and being slightly miscued.

If there was something shit-can about the record it was the recording. A superior recording of the same song was released across the ditch with an Australian recording of ‘Stormy Winds’ on the flipside.

The New Zealand release featured a version of ‘You’re On My Mind’ written by the New Animals organist Dave Rowberry. The Animals’ B-side and album track was rumoured to have been handed over on the Australian leg of the Animals tour by Rowberry although Williams doesn’t remember that happening. More likely was the Rebels’ hearing the US-only Animalism album track.

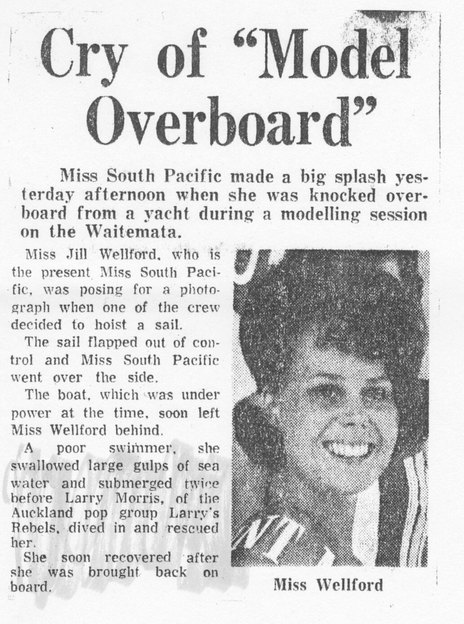

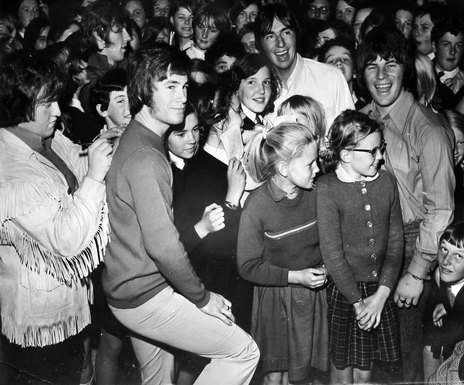

On the group’s return to Auckland in July, Russell Clark arranged a fake rescue by Larry of a Miss New Zealand contestant after she “accidentally” fell overboard on a dance cruise. The talk, however, was mostly about the group’s new live show, which included a psychedelic light show — the first in New Zealand.

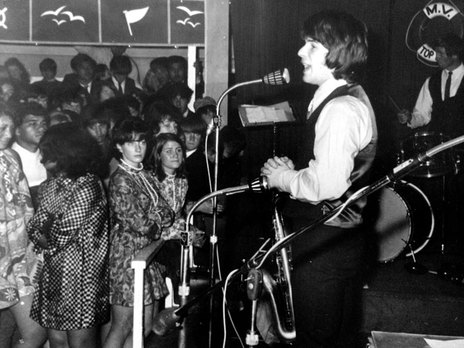

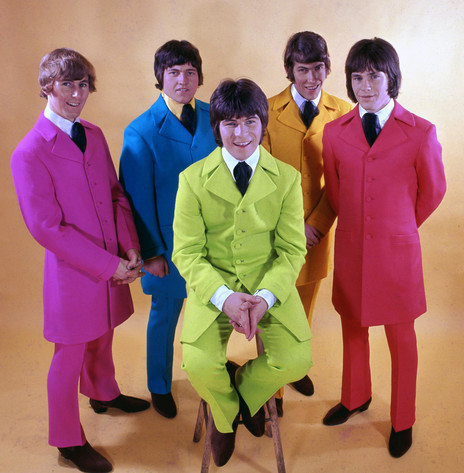

John Williams: “Ron Blackmore found us large rehearsal rooms in Prahran in Melbourne to rehearse the show. We had coloured suits and scarves. We had smoke bombs, a strobe light, you name it. We put that act together to make a forceful impact on the scene. The first time we released it was at the Moomba Festival before one hundred and fifty thousand people at the Myer Music Bowl in Melbourne, and we just took the show apart.

Come August 1967 and the Rebels were on the road again in New Zealand playing The 1967 Loxene Golden Disc Spectacular with The Avengers, The Gremlins, Mr Lee Grant and Sandy Edmonds.

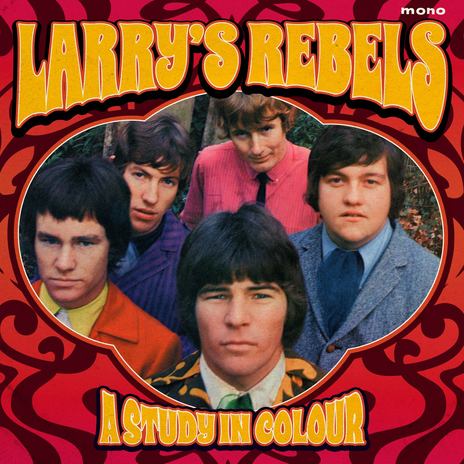

Larry’s Rebels first and only album, A Study In Black, was recorded with Garth Benfell at the Shortland Street NZBC TV studios in Auckland, and released in the summer of 1967. The highly collectible record is a hodge-podge of disposable pop and classy R&B tracks. Of note is ‘Inside Looking Out’, a piece of Animalistic urban blues, and the Williams/Morris original ‘Shakin’ Up Some Soul’, a hard out frugger that kept Rebels fans bouncing.

There’s also a gem of a ballad called ‘Let’s Think Of Something’, which was re-recorded with former Rolling Stones engineer Roger Savage at Melbourne’s Armstrong Studios. It became Larry’s Rebels’ third New Zealand hit single in September, rising to No.4 in the charts, and eventually winning its composer, New Zealand pop performer Roger Skinner, the 1968 APRA Silver Scroll Award. Equally strong is the flipside, ‘Stormy Winds’, an aching ballad that had appeared on A Study In Black, but was re-recorded in Sydney.

Larry’s Rebels spent much of 1967 and 1968 in Australia. With bigger crowds came bigger temptations, as many New Zealand acts who made the trans-Tasman hop had discovered.

“We stayed in the Plaza Hotel in Kings Cross where all the bands stayed,” says Williams. “The drug scene was pretty bad. Our band was clean cut — Nooky, Viv, and I — I can’t vouch for Larry.”

“The band was getting strip-searched outside venues, and coming back into NZ. Larry had heavy mates in Sydney who liked to hang out with rock stars. One came back to New Zealand with us. Outside venues people would be waiting, saying, ‘Where’s Larry?’”

Back in the Shaky Isles, the hit singles kept coming. ‘Dreamtime’, a Williams/Morris original, hit No.4 in November 1967. This is the song where Larry finally grabs firm hold of that big beat ballad he’d first attempted in the group’s early days, and nails it.

With its strings, heartbeat bass and storm wind effects, ‘Dreamtime’ was a well-produced, musically assured track which displayed none of the hesitancy of ‘This Empty Place’. For fans of the tougher Rebels sound, a hard driving version of The Easybeats’ ‘I’ll Make You Happy’ was on the flip.

Follow up single ‘Fantasy’ (backed with ‘Coloured Flowers’) was the group’s less than successful take on psychedelia. Williams: “‘Fantasy’ begins with a harp. We had an orchestra in there. I couldn’t believe Russell Clark would spend the money on a full string section. We played ‘Fantasy’ live, but it was not a set regular. We never had a set repertoire.

“‘Coloured Flowers’ was a nothing song. The band wasn’t sure which way pop was going and we were experimenting with fuzz and wah. That group could go anywhere and play. It could adapt. We could play anything because we’d experimented all those sorts of sounds.”

They had more luck with ‘Halloween’, a freaky piece of flower pop – and its hard bitten pop flipside, the Hans Poulsen-penned baroque ballad, ‘Everybody’s Girl’, which restored Larry’s Rebels to the New Zealand charts in July 1968, climbing to No.6. Like all of the Rebels’ New Zealand hits it failed to impact on the Australian charts.

It was on the Blast Off ‘68 New Zealand tour that the pace finally showed. Terry Rouse suffered a nervous breakdown and decided to leave the band.

Larry’s Rebels cut their next single, Jimmy Webb’s country soul ballad ‘Do What You Gotta Do’ with organist Brian Henderson and replaced Rouse with Mal Logan, a Sydney based player, formerly of Whanganui’s The Look and Auckland’s The Green and Yellow.

The stress that caused Rouse’s departure was telling on the group, who’d reaped plenty of popularity but little money. “Impact blatantly exploited us,” Williams says now. “We were very naive. We knew nothing about publishing. We knew nothing about royalties. We were led along by pieces of string. They saw a good thing and they took it. We were a huge money-spinner for them. We were earning good money in Australia, but we never saw it. We’d get sold off to Ivan Dayman in Brisbane, go for twelve dates and end up playing twenty to thirty.”

“We were paid weekly on a Friday. A weekly wage, plus an allowance on the road. Larry took over control. He was the paymaster when Russell wasn’t around. We knew we were being exploited but there was no way we could get out of that contract.”

Williams, a fair man, can see the upside. “They did it right even if we were a workhorse to them. Singles rolled out. Jamborees were set up. Tours kept going at a relentless pace. They’d have singles out within a week of recording, pressed with posters out. We’d be on the road and we’d hear it first on the radio.”

That’s where they heard ‘Do What You Gotta Do’, which rose to No.6 in September 1968.

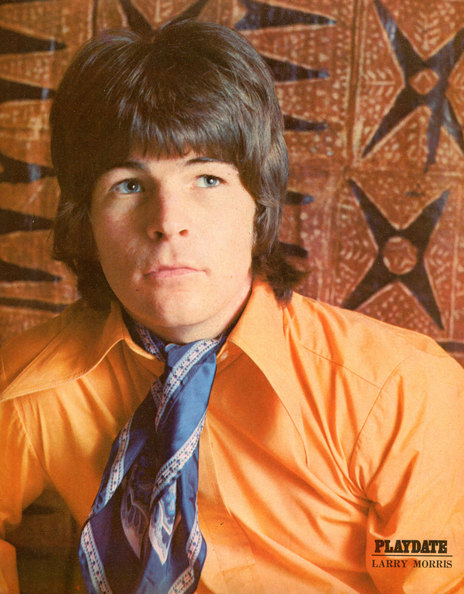

Larry, recently married, doing what he had to do, and eyeing a solo career, left after an argument with management at a show at Whitianga in early 1969 to take on a DJ slot on Auckland’s Radio I.

The group’s parting shot was a career highpoint, a whooping (and renamed) version of Paul Revere and The Raiders organ-driven ‘Mo’reen’. The fans loved it, pushing it to No.4 in February 1969. It’s a 1960s New Zealand classic.

Larry’s replacement upfront was blues wailer Glyn Mason, who learnt his chops in Wellington R&B bands before moving to Auckland. That’s him out front on the renamed the Rebels’ surprise No.1, ‘My Son John’ in March. Flip it and you’ll find one of the group’s most powerful rockers, the band original, ‘Passing You By’, penned in the back of the van on a long Australian road trip.

With Madrigal, an uneven album of pop standards captured by talented engineer Wahanui Wynyard, in the can, The Rebels moved permanently to Australia in March 1969.

When the intriguingly titled follow-up, ‘Can You Make It On Your Own?’ flopped, the tide receded, and in January 1970, the Rebels, one of the best New Zealand pop groups of the 1960s, disbanded. It had been a long eight years. Guitarist John Williams was not yet 20: he would later recall that already, he had lived a lifetime.

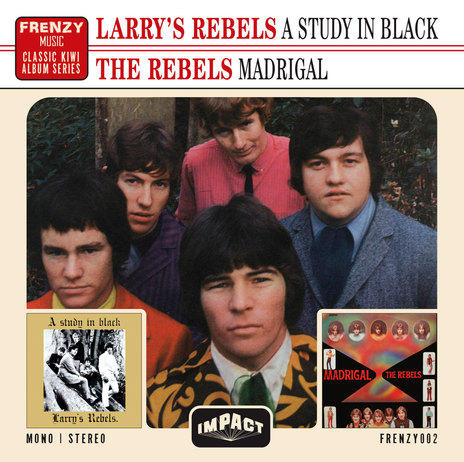

In June 2013 the albums by Larry’s Rebels, and the Rebels (A Study in Black, and Madrigal) were reissued by Grant Gillanders’ Frenzy Music on a single CD. Frenzy followed this in 2020 with The Complete Singles, A’s & B’s; a deluxe edition included a book and a bonus CD of demos from 1964-65.

On 22 October 2020 it was announced that Larry’s Rebels were inducted into the The New Zealand Music Hall of Fame.

--

Read more about Larry’s Rebels on AudioCulture

Larry’s Rebels part 1: Long Ago, Far Away

Larry’s Rebels part 2: Dream Time

The Larry Morris interview - “We Were Just Hopelessly, Crazily Rock ‘n’ Rolly!”