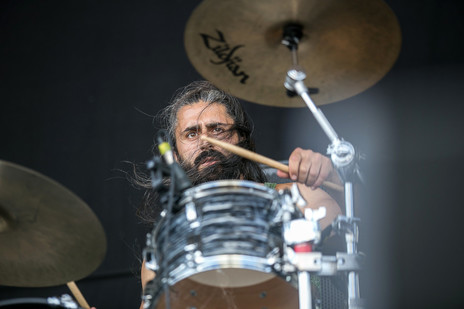

It takes until mid-winter before a call can be arranged with the other members, and Karlis, a Berlin-based software engineer, has come from heatwaves for a family holiday in chilly Hawke’s Bay. He laughs stoically as he tells me that they’re off to Dunedin next. Phillips works as a curatorial manager at the Canterbury Museum, and is joining from Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Not long after I interviewed Dingemans, the band’s friend and mentor Steve Albini died, and when I spoke to Phillips and Karlis, the music community was mourning the recent loss of Martin Phillipps. During the condolences we are reminded that it is also 30 years since HDU began.

1992-1994: From Eskimo Chain to High Dependency Unit

Karlis grew up in Heretaunga Hastings, and Phillips and Dingemans in Karanema Havelock North. The three played together in a band called Eskimo Chain, the line-up of which included vocalist Duncan Field, and Phillips’s older brother Fred on bass, who was the first to shift to Dunedin in the early 1990s. In 1992, Karlis went to study physics at Victoria University in Wellington, and Phillips and Dingemans followed Fred to Dunedin. Karlis tells Phillips of a letter that he has recently archived, in which the band implored him to join them in Dunedin. The “impassioned” missive convinced him to eschew plans to attend Wellington Jazz School and head south.

Dingemans recalls that the first Eskimo Chain gig in Dunedin took place in March 1993. They did some recording with Stephen Kilroy at Fish Street Studios, but the band broke apart a year later, which paved the way for HDU: “Dino, Neil and I just started jamming and one of the revelatory moments was when Neil plugged me into two amplifiers. He had a second guitar amp, and he was playing bass, so he thought, ‘I'm going to try this.’ There was this tremolo pedal, and all of a sudden there were two amps going. And I never looked back really.”

When I ask Karlis and Phillips what they remember of those first sessions, the drummer leaps in: “Oh, I instantly knew we had something. I remember going, ‘this is great. This is what we were trying to do.’ It felt like something different and new and interesting.”

Phillips, who had switched from guitar to bass, tells us he did not have the same experience as his bandmates. “I felt differently. I just felt really insecure.”

“Turn it up louder, right?” says Karlis.

“Yeah, exactly. I knew that it was about trying to channel emotion, and for me that felt quite uncomfortable. And then putting that on a stage in front of people was even worse. Stuck at it, though.”

He certainly did, possibly because the band did turn it up, which prompts me to ask if the “heaviest band” mantle was something sought or imposed? The former, says Karlis, because in Dunedin, “there was a punk influence like loud and raucous, but it wasn't heavy, and I think we brought a bit of that Hawke’s Bay bogan.”

Phillips joins in: “Yeah, there were wiggy bands and that, but not really heavy bands.”

In both interviews, the band notes the “Mind. Blown” impact of live performances by New Zealand bands such as Dead C, King Loser, and Solid Gold Hell. Yet, HDU found their own sound early on, something that Phillips puts down to “general laziness” on his part, because he was a guitarist playing bass, and instead of learning from other bassists, either played his “guitary stuff or [making] it really simple.”

“Those first rehearsals,” says Karlis, “what came out didn’t seem like anything I was particularly familiar with.”

Possibly because HDU were also influenced by another sound of the early 1990s: techno. Dingemans recalls that in 1992, “Dino and I went to an Entrain party. I dropped some acid and after forty-five minutes started dancing. I'd never danced to techno before and it was like, ‘I love this.’ We didn't start writing doof-based music, but …”

Karlis picks up the story: “going to those outdoor raves, and just seeing the parallels [with] all the other music we loved had a really natural influence. The way the guitar sounds were shaped, they were sort of echoing. Like, if you listen back to how the guitars are played and bounce around. You can hear both Pink Floyd and Goa trance in there.”

1994-1995: first gigs and recordings

The first HDU shows were supporting Age of Dog at the Empire Tavern, on 15 and 16 May 1994. Two of their earliest fans were Natasha Griffiths and Dale Cotton, the former becoming their manager, and the latter their sound engineer and “fourth member”. Dingemans notes that Cotton was the drummer for Age of Dog, and Griffiths was managing them: “They were a couple then and very tight around their love of the music scene and music in general.”

Karlis also remembers Cotton from that first gig, specifically his offer to record them at his studio. He says that hearing themselves on tape was like “the first time seeing yourself in a mirror”. The sessions produced two cassettes: an eponymous three-track in 1994, and ‘The Vital System’ single in 1995, the latter of which Phillips has forgotten about, prompting the following exchange:

“What was on that second cassette?”

“Aah, it was that miserable one.”

“That’s all of them, Dino.”

“I can’t remember any names. That really slow, grindy miserable one.”

“Sounds great.”

Cotton clearly thought the same, because he went on to engineer most of their recordings. “Dale had a profound influence on us,” notes Dingemans. “We learned a lot. He had a great creative approach to recording. We did some amazing work with him.”

The live shows and cassettes earned their “miserable” sound a dedicated audience, which also included Flying Nun management after Griffiths started working at the label and arranged an audition. “HDU wouldn't have achieved anything without Natasha,” says Dingemans. “I mean, we would have done okay, but she knew what she was doing.”

The gig was at Squid with My Deviant Daughter, another trio from Dunedin, and at the end HDU were offered an opportunity with Flying Nun. The band expected to record a seven-inch single, and Dingemans stayed on in Auckland to meet manager Paul McKessar, who told him the label wanted an EP. When asked who they wanted to produce it, Dingemans wrote down Steve Albini and Kevin Shields. “You knew it wasn't going to happen,” he says, “but I think [Flying Nun] decided to send Steve some stuff.”

1995-2008: the Flying Nun recordings

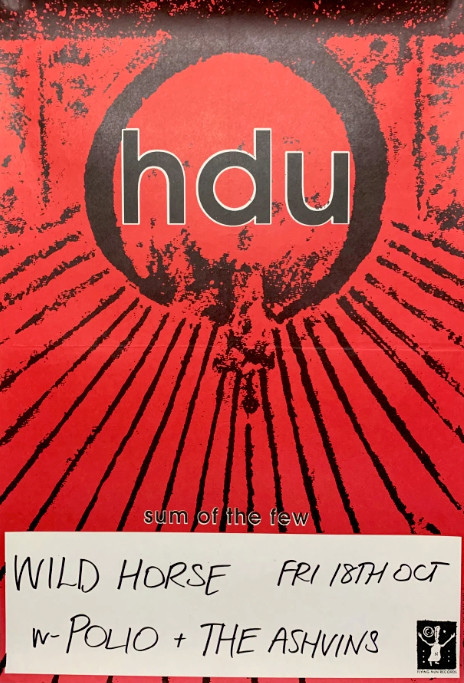

Cotton produced the 1995 EP Abstinence: Acrimony, and the 1996 debut album Sum of the Few, which was duly sent to Albini by Flying Nun. Albini responded with a letter to the band. Dingemans tells me there had been talk of a US tour, and the musician/ producer was excited, writing that he was “jumping around … saying ‘High Dependency Unit are coming. High Dependency Unit are coming.’”

That tour never materialised, but the letter was the start of the band’s relationship with Albini.

In 1996, Sum of the Few turned up in my review pile, and I was impressed with how HDU used volume like an instrument. However, my jumping-around moment was 1998’s Higher ++, where the Higher EP (1997) was re-released with remixes by emerging electronic producers. I was particularly taken with the “beautiful, lilting, transporting” Soundproof version of ‘Lull’ (The Press, 1998), a track that continues to grace best-of lists and radio shows. It was Karlis’s idea to get their music remixed: “I’d done a few remixes and wanted to see what could be done when we collaborated with some of our favourite electronic music creators.”

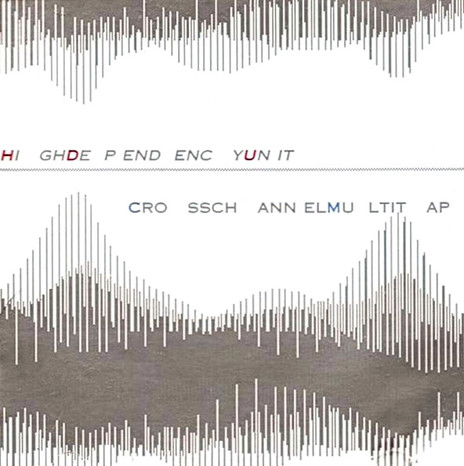

There was another nod to dance music in the title of 1998’s Crosschannel Multitap, named after the effect of being at The Gathering and standing at an aural crossroads where you could hear the beats from multiple dance zones. For the second album, they tried a new approach with the band recording live directly onto a computer hard-drive and then editing it, so that they could capture the live feel, but still manipulate it.

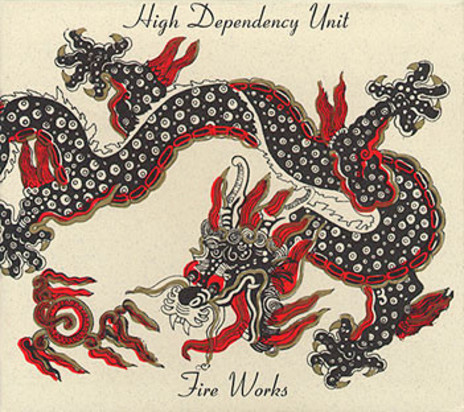

In 2000, the Memento Mori EP was released, and HDU were asked to support Albini’s band Shellac on a tour of Aotearoa/New Zealand. Over 14 dates in 14 days, they got to know Albini well enough that he invited them to go on a tour of the United States. They spent five weeks on the road travelling from New York down to Dunedin (Florida), and back to Chicago. There, they spent two weeks in Albini’s Electrical Audio, where Cotton got to play “fourth member” at the desk of the legendary analogue studio. Fire Works was recorded over 12 days, which gave it a stripped-back raw sound. HDU have described it as the sum of all their influences.

Fire Works was released in 2001, and HDU did a four-date tour of New Zealand, but five weeks on the road in the US, followed by the intense recording period, had taken its toll. Without breaking up, they took a break to focus on their jobs, young families, and mental health.

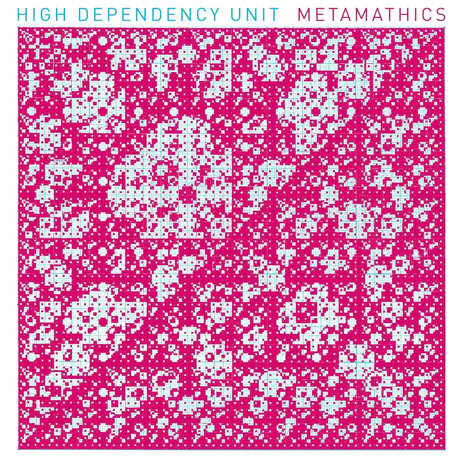

Fans had to wait five years for 2006’s ‘Tunguska’ single, featuring a Signer remix, and a cracking live version of ‘Concentricity’ from Fire Works. ‘Tunguska’ was a shimmery teaser for HDU’s fourth album, Metamathics, released in 2008, after a computer mishap in which some of the original recordings were lost. This time Cotton mastered the album, but it was a combination of Bevan Smith, David Wernham, and Lee Prebble in the recording role. Weighing in at six lengthy dynamic tracks, Scott Kara writing in the NZ Herald called it “a journey from bedlam to bliss and back again.”

2008-2024: post-HDU and live tours

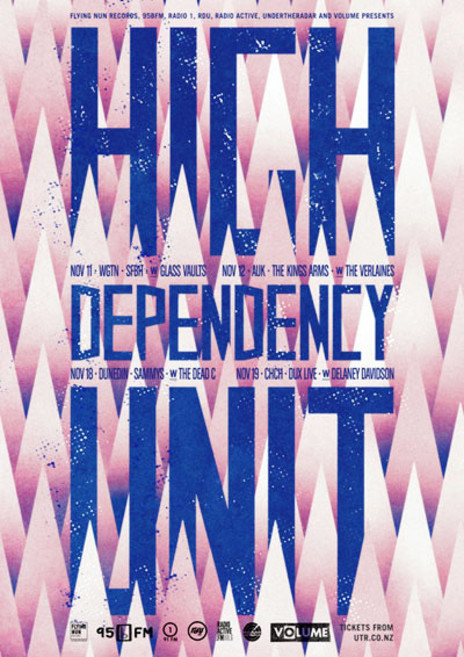

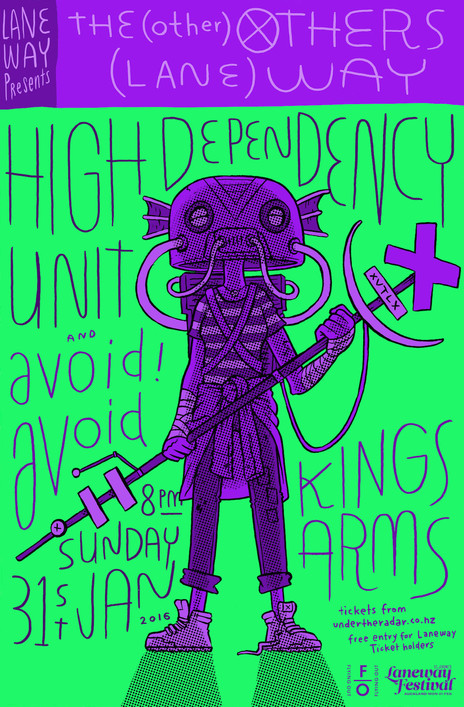

Since 2008, HDU have toured twice: the Flying Nun 30th anniversary tour in 2011, and another in 2016, when they played at Laneway Festival.

Meanwhile, Dingemans says he “just tries to keep playing” through his musical outlets Kāhu (solo) and Kāhu Rōpū (trio) with Sam Healey (bass) and Rob Falconer (drums). Thanks to the “tyranny of distance” his other act, Mountaineater with Anaru Ngata (bass) and Chris Livingston (drums), is on hold, but their 2013 eponymous album is another testament to the behemoth power of a guitar-bass-drums line-up.

Phillips continues to “play a lot at home” and says he sometimes jams with a mate, who “occasionally threatens to organise a gig”. Meanwhile, Karlis has formed the band Great Barrier with Jason Kerr (of My Deviant Daughter), and occasional cameos from Dean Roberts [Roberts died in August 2024]. He describes it as “very much a post-HDU band – droney and improv/edit based” and mentions a forthcoming album.

Those who’ve experienced HDU live will know it is not an overstatement to say something magical happens when the three play together, their soundscapes sprawling so leisurely you assume it is improvised. Karlis explains it’s not so much pure improv, as spontaneity, and that they like to identify spaces “to stretch out and just let it happen”.

Any chance that might happen again? Across both conversations, they clearly still feel that magical musical bond, and Karlis notes, “It’s just a matter of getting off our arses and organising it.”

It’s not quite enough to warrant jumping around saying “High Dependency Unit are coming” but here’s hoping HDU might yet return to claim their stake as one of the nation’s heaviest live acts.