The daughter of a working-class Irish farmer and a classical piano teacher, Philippa McIntyre grew up in Whanganui and Nelson. Thinking back to her childhood, she remembers being bullied and ostracised for living on the wrong side of town. “I was bookish, nerdy, and I didn’t have any cool clothes,” she says. “Looking back, I now see with clarity that it was a really tough time for me as a kid. Being bullied really impacted me in a number of ways, but it also set me up for independence.”

Unable to depend on most of her peers, McIntyre found solace in literature and music. “Music was my arena,” she enthuses. “I sang in church choirs, had main parts in school musicals and played classical piano from age five. The one place I was 100% confident was music.” In part, she credits this confidence to the values her mother instilled in her. “I was raised in a household where gender equality was 100% there,” she continues. “I never used to realise that was the water I was swimming in, but ultimately, it conditioned me to take the risks I have later in life.”

McIntyre's musical interests shifted from classical to post-punk, alternative rock, and grunge

When she was in her mid-teens, McIntyre's musical interests shifted from classical music to post-punk, alternative rock, and grunge. “I fell in love with The Cure, Pixies, Sonic Youth, and the Stone Roses,” she remembers. By this stage, her family was living in Nelson, where she’d made some friends to obsess with over music. “Music was at the centre of everything,” she says. “It was the most important thing in my life.” Outside of school, she’d hang out at the legendary, now-defunct independent Nelson record store, Everyman Records, and a local community access radio station. Soon enough, she was hosting the occasional radio show on air. “I loved the whole sort of special, quiet and exciting vibe of it,” she continues.

After finishing high school, McIntyre headed to Christchurch for her first year of university. However, as the months went by, she realised it wasn’t enough. The following year, she moved to Wellington to continue studying towards a Bachelor of Arts degree. There, she lived with her older sister and started spending most of her evenings watching bands play at a small venue on Vivian Street called Hole In The Wall (now Valhalla). “There was a really strong rock scene at the time, but some of the bands were crazy and experimental,” she says, enthusiastically.

Initially, McIntyre wasn’t a fan of electronic music. However, after moving into a flat with two girls who were dedicated ravers, she found herself warming to the sound of mid-1990s jungle, drum & bass and techno. “I loved going out with these girls and we had a great time,” she says. “They became really important to me, and I stopped being a bit of a lone wolf. I’d found a crew and a community.”

Discovering House Music

On New Year’s Eve 1996, McIntyre and her friends went out to the La Luna nightclub on Dixon Street to see the German acid techno producer-DJ duo Hardfloor play. During their set, she wandered into the side room, where she was captivated by the sound of two local DJs, Andee and Schmoo, playing deep house. “They were playing records from Mood II Swing, early Paper Recordings, early Guidance Recordings,” she says. “There were only about 20 people in the room, but I had a full-blown spiritual experience on the dance floor. I was like, this is it.

Several days later, she wandered into one of the local specialist dance music record stores of the era, Flipside, and purchased her first house music 12"s. From there, she quickly dived into Chicago House (à la DJ Sneak and Derrick Carter) and the Parisian French Touch scene, immersing herself in a world of disco loops, machine beats and funky basslines.

Not long after, a friend from the Auckland scene, Andy Pickering, came to Wellington to look after a sick family member. On arrival, he moved in with Philippa, bringing turntables with him. “I started learning to mix on those turntables,” she says. “I’ve actually still got them.” Over the following year, McIntyre immersed herself in the local house music scene. “At the time, the scene was pretty golden,” she continues. “It was DJs like Clinton Smiley, Andee and Schmoo, and there were these great parties called Come Together.”

“What grabbed me right away [about house music] was its attitude,” McIntyre explained during an interview with the MusicIs4Lovers blog in 2024. “House aimed to promote strength, unity, acceptance, community support, warmth – which were essentially messages of hope from the African-American and Hispanic communities who birthed the music. It was revelatory – it blew my mind. Black music came along and rolled like a steam train and through my imagination. I consequently discovered hip-hop in a big way, and from there, soul, jazz, disco, and so on – but as a fan only. As a DJ, I played house.”

A move to Auckland

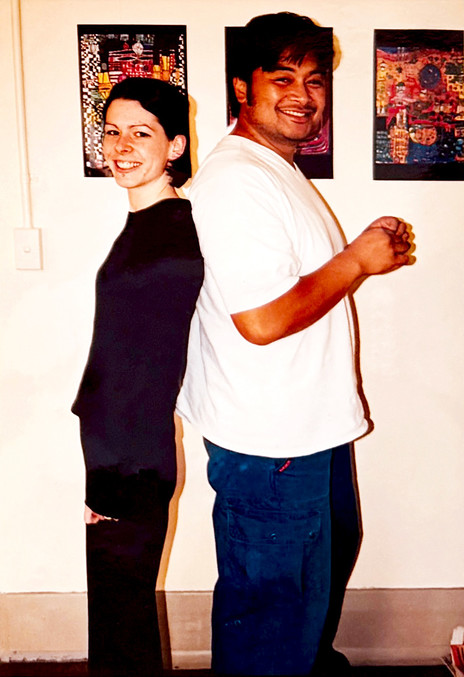

At the end of 1997, McIntyre relocated to Auckland with Pickering. Not long after arriving, she took on a day job at one of the seminal New Zealand dance music record stores of the era, BPM Records. At BPM, McIntyre worked alongside a range of seminal New Zealand dance music champions like Greg Churchill, Geoff Wright (aka DJ Presha), Nick D, the store’s owner, and AudioCulture’s very own founder, Simon Grigg.

In a conversation with The Insider for the respected Ban Ban Ton Ton blog in 2022, she reflected on its culture. “I think what was key about record stores in those days is that this was pre the internet age taking off – there was no social media,” she said. “So record stores served as a central point of exchange and interaction – obviously if you were a music fan you’d buy records, but it’s also where you’d go to pick up flyers and find out what was happening that weekend or who was flying into play, gossip over who had been playing well recently versus who hadn’t, which records were hot, who had hooked up with who and so on. It’s also where fans would get to chat with DJs in the daytime. Record stores were fundamental to a healthy local scene. Record stores are still important now, of course – but in those days it was all we had.”

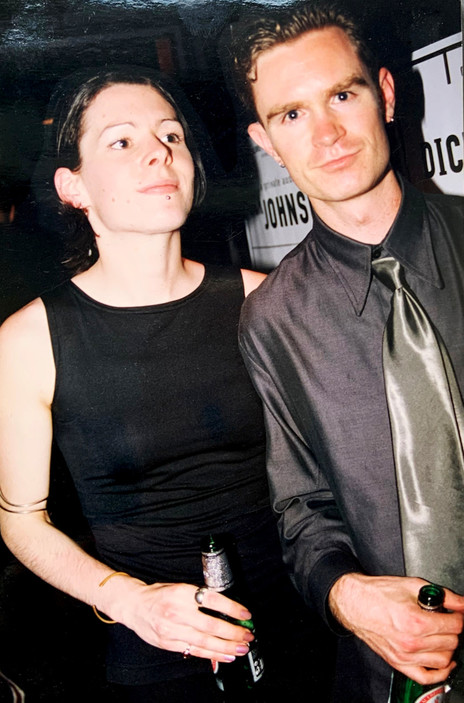

At the same time as McIntyre was working at BPM and finding her way into the DJ scene, Pickering and their flatmate, Tim Phin, were working to get the magazine Remix off the ground. These days, Remix is a glossy quarterly fashion, lifestyle and culture title, but at the time, it was a scrappy music street press publication with big dreams.

Alongside publishing the magazine, they also threw Remix parties at the Calibre nightclub inside St Kevin’s Arcade on Karangahape Road. Soon enough, she was playing at their shows and had made friends with Calibre’s manager, DJ Roger Perry. “Roger was really good at bringing together people from different parts of society,” McIntyre says. “He was also someone who represented high standards and respect. He helped us understand respect, working your way up, and having a deep understanding of culture. He really mentored us.”

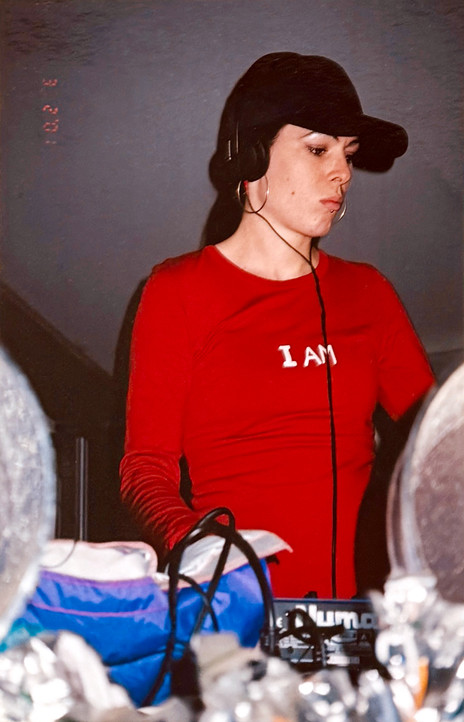

McIntyre quickly built a solid reputation on Auckland’s house music scene

McIntyre quickly built a solid reputation on Auckland’s house music scene through her daytime work at BPM and DJing around the city by night. In 1998, she was voted best-up-and-coming Auckland DJ by a poll of Remix readers. Things went to the next level for her near the end of 1999, when Remix began attaching mix CDs to the cover of the magazine. “I did their second mix CD,” she says. “That really helped me out. Actually, it put me on the map. From there, I was able to organise tours around New Zealand. The prestige that came from playing some of the bigger clubs and being supported by Remix made it easier for me to carve my own way.”

In 2000, McIntyre was selected to attend the Red Bull Music Academy in Dublin. After returning to Auckland, she was awarded best up-and-coming DJ at the student radio music awards. Reflecting on the early 2000s, she recalls working a circuit where almost every city in New Zealand had a nightclub that was sympathetic to house music. “I was playing for about 15 different venues around the country,” she says.

Although 1990s and 2000s dance music is sometimes historically presented as a boys’ club, McIntyre remembers playing alongside skilled female DJ talents such as Chelsea, Claire Del, Angela Jepsen, and Camile. That said, as history teaches us, progress doesn’t always follow a straight line trending upwards. As she told The Insider in her Ban Ban Ton Ton blog interview, “There were actually about six or seven decent female house DJs in Auckland in the early 2000s, but it never really grew from there. I think it’s looking healthier now: we’re really seeing a blossoming of ladies behind the decks presently, aren’t we? I’m very happy about this.”

Chicago Disco

In 2002, McIntyre recorded a mix CD for the New Zealand label, distributor and publishing company In Music as part of their In Music series. The next milestone in McIntyre’s DJ career was the establishment of her bi-monthly Auckland club night, Chicago Disco, and its subsequent evolution into a regular national tour. Alongside this, she also started hosting the Friday Drive show on George FM, a position she held for seven years. “I did six Chicago Disco tours,” she says. “At the start, we’d get clubs full all over the country. By the end, I was only playing six venues, and the promoters were all saying house music wasn’t pulling the crowds anymore.” Having enjoyed a golden run during the late 1990s and early 2000s, house music began to decline in New Zealand following the local rise of drum & bass and dubstep.

Hand in hand with the influence of Pickering and Perry, McIntyre also learned a lot by playing for Andy Meek, who owned the adjacent Ink and Coherent venues on Karangahape Road. “Ink was a community hub for a lot of different people,” she says. “Andy really looked after me. I played for him most weeks for eight years.”

After things ran their course at BPM Records, McIntyre studied audio engineering at MAINZ. When she’d completed her diploma, they invited her back to consult on the launch of their electronic music production and DJing programs. “They asked me to apply for a job there, which I was stoked about,” she says. “I worked there for three and a half years while [the American producer and DJ Matthew Chicoine aka] Recloose was running things.”

Despite acquiring the skills to produce, McIntyre was hesitant about releasing her own music at the time. “I was a big fish in a small pond, and it made me a bit complacent about my skills and knowledge,” she says. “In reality, I was procrastinating. I could sense that it was going to take ten years of hard work before I’d really be able to release music I was happy with.”

Berlin or bust

In 2012, McIntyre went on a trip to Berlin. As she told RNZ’s Tony Stamp during an interview for the Music 101 show, “I went to Sonar Festival in Barcelona, and I went to Berlin afterwards. I loved both experiences. Both experiences blew my mind. In Berlin, I saw lots of people walking around in Doc Martens boots, and it was just so chill. I was like, this is a bit of me. I could live here.”

In 2013, McIntyre took a leap of faith and moved to Berlin. “I was finding it harder and harder to see a pathway for myself in New Zealand,” she admits. “Because I was so full of myself, I thought I could come to Europe and people would give a fuck.” In reality, on arrival, Berlin was spectacularly apathetic towards her history as a DJ in New Zealand. “I went through about three years of grief over feeling like I’d lost my music career,” she continues. “Actually, it was the best thing that ever happened to me, because it forced me to grow up. I realised that when he talked to us about standards, Roger Perry was right. The reality is that the world owes you nothing. If you want to make an impact, you have to contribute.”

In Berlin, McIntyre took on a job as an electronic music production and performance tutor at dBs Berlin (now Catalyst), a creative arts and technology learning institute located within the celebrated Funkhaus building. Work and the diversity of arts and culture available throughout the stone city kept her going until she regrouped and threw herself into music production. “The more I did it, the more obsessed I became with it,” she says. “I grew my creative muscle, kept learning, and slowly things got better and better. I was also meeting incredible people and going to incredible places. People talk about famous Berlin clubs like Panorama Bar, but there are eight or nine good house clubs in the city. The club culture and history here are incredible.”

Realising a dream

Ostensibly, McIntyre creates house music rooted in the traditions of disco, funk, soul, and jazz. That said, she keeps her production influences open-eared. In an interview with the 15 Questions blog, she noted that her influences are constantly shifting and changing, before highlighting the importance of the 90s New York hip-hop and neo-soul collective, the Soulquarians, to her sound. While we talk, she also mentions German krautrock and kosmische musik, ambient, indie, and French musique concrète.

In 2018, McIntyre started thinking about setting up a record label and releasing her own music. Not long after, she made a new friend while partying at Panorama Bar, who would later become her press agent. The following year, she launched At Peace Music, marking its debut with a four-track EP titled Pronoia. Throughout 2019, she released a series of digital EPs through the label, which, thanks to her publicist, landed in the inbox of the British deep house producer and DJ Jamie Odell, aka Jimpster, from the longstanding Freerange Records label.

“After a year of that, I got a message from Jimpster asking if I’d be interested in submitting any demos for Freerange,” McIntyre says. “I knew he was listening, but that request absolutely blew my mind.” In 2022, she released a four-track EP titled There’s A Ghost In My Synthesizer through Freerange. On release, McIntyre’s work was praised by the When We Dip and Ban Ban Ton Ton blogs for its French Touch, jazz, and Philly Soul influences. After spending years dreaming about finding some success as a producer, she’d finally made it onto the ladder. “Things just took off from there,” she says.

McIntyre’s work was praised for its French Touch, jazz, and Philly Soul influences

In the wake of There’s A Ghost In My Synthesizer, Philippa released an EP of sample-based deep house titled Rainy Nights through London’s SlothBoogie label in 2023. Later that year, she released the Latent Magic EP through Freerange Records. In 2024, she reconnected with SlothBoogie for the Port Chalmers EP, followed by a collaborative release with Jimpster, the Blue Skies EP for Montreal’s Lazy Days Recordings. Over the first half of the 2020s, she was also tapped to produce remixes for Jamie Clarke, House of Downtown, Roach Motel, Fat Freddy’s Drop, and Cosmo Klein & The Campers. From there, she began DJing events for SlothBoogie, Sonar Kollectiv, and Glitter Box Ibiza, as well as recording DJ mixes for a range of internet radio platforms.

“I’ve got another EP coming out on [Swedish label] Local Talk towards the end of the year,” McIntyre said early in 2025. Alongside her efforts for labels, she’s also launched her own release project, Quiet Fire. “It’s going to be a Bandcamp-only digital release once a month for a year,” she explains. “The whole idea is to have creative consistency without being mediated through someone else. The releases could be experimental or club bangers, but I’ll be in charge of the whole process. It’s a low-stakes, no-pressure way to keep me chugging along writing music.”

“Things look good and successful at my end right now, but I’ve found it to be a bit of a headache,” McIntyre says. “These are really big and complex questions, but as an artist, it’s worth asking yourself at what point do you feel like you’re successful or have made it. I don’t feel like I’ve done either of those things yet. What I have done is meet a really cool community of German music lovers like Daniel Best [from Sonar Kollectiv] who has been helping me get gigs, do remixes and connect with people.”

Having been involved in DJ culture for nearly three decades, McIntyre has had ample time to reflect on why she has spent a lifetime pursuing music. “I want to be able to help people feel good about being alive and express beauty,” she enthuses. “I also want people to recognise that magic is actually a thing – the world is mysterious, wondrous, shimmery and weird. It’s hard to put into words, but I try to paint shades of shifted reality with my tracks. I feel like I was born to create music that reminds people that things will be okay. Life is still worth living.”