AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Tommy Kahi

He claimed to have known everyone and done everything first, including forming the first all-electric band in New Zealand in 1950, and introducing rock ’n’ roll to the shaky isles after hearing Bill Haley on shortwave radio.

Tommy was born 30 October 1924 in Rawene, Hokianga. His father Moses worked on the ferries, and eventually moved to Auckland to take up a job plying the Waitematā harbour and Hauraki Gulf. Moses also played violin in local dance bands.

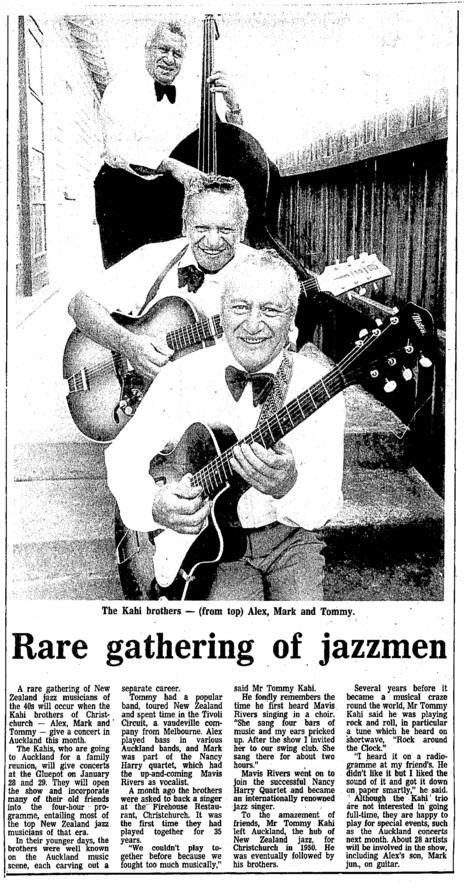

In an oral history interview done in 1993 with music historian Roger Watkins, Tommy remembered hanging around with his musician brothers Alex and Mark at Lou Mati’s Polynesian Club on Karangahape Road in the 1950s, just up the road from his Greys Ave home.

“(Mati) had a chap named Robinson on electric guitar. I looked at him and asked him, will you teach me the electric guitar? He said, ‘go away little fellow,’ and I was so wild, I said right I’m going to teach myself. I was seven years old. I said ‘I’m going to beat you.’

“The Salvation Army band used to play right in front of Polynesian Cub. I would listen to them play. I could do exactly what that drummer was doing.”

In the 1993 Alexander Turnbull Library oral history interview with Watkins, Tommy said he started playing on a Woolworths ukulele before taking over brother Alec’s guitar.

“I used play the guitar to the radio. All good stuff, jazz dance band music. And I’d listen to the chord changes, see what key it was, go up the fret board till I found the key. I could hear these chords, 7ths, diminished, augmented – I learnt all these things, taught myself.”

“I started to play ‘Whispering’ on the guitar. Well the people went mad”

The first song he remembers learning was ‘Whispering’. “I went to Lou Mati and said, ‘Lou can I play your guitar now.’ I was shaking like a leaf – he said, righto ... so I got up on stage and he gave me the guitar, and damn me I went to play a chord and broke an E string. That made it worse. So I fixed it and tuned it. I started to play ‘Whispering’ on the guitar. Well the people went mad, they clapped and clapped. And Lou says, go on, play the next one. And I played ‘Bye Bye Blues’ and all these other numbers I knew. Well I got a tremendous hearing.”

In another version – which Tommy told the Women’s Weekly in 1978 – he described being discovered at age nine by Mati’s cousin, Gus Lindsay, when he was playing guitar while walking along a road in Waiheke, where he would spend weekend afternoons.

He played in Lindsay’s band for three years, and remembered a homemade (Hawaiian) guitar, electric, made by Tony Lindsay, brother of Gus. “It used to hurt my fingers because I had baby fingers. I started to tape my fingertips. Gus used to say, ‘you got those tapes on Tom? No! Show me your hand’ … he’d pull them off.”

He then joined Epi Shalfoon, whose band held the residency at The Crystal Palace Ballroom in Mt Eden. Tommy credits Shalfoon with teaching him much of the craft of a bandleader. “He was a tremendous showman. He used to kick me in the shins and say ‘you are playing for me and for those people down there and you will do what I want and what they want. What you want to play, you can do at home on the washhouse’,” he told the Weekly.

By his mid-teens Tommy had his own band of young hopefuls. “I trained my fellows up to perfection. I used to have this girl Betsy Williams on piano, she used to teach me. She lived in Pt Chevalier, and we used to go there by tram – drummer, Wally, John, all the boys … she’d get stuck into them … hard training up everybody. So much so I’d be sitting on the tram by myself, no one would talk to me. I was very hard as a bandleader, until I got them up to perfection. It had to be 100 percent as far as I was concerned, 99 percent was no good.

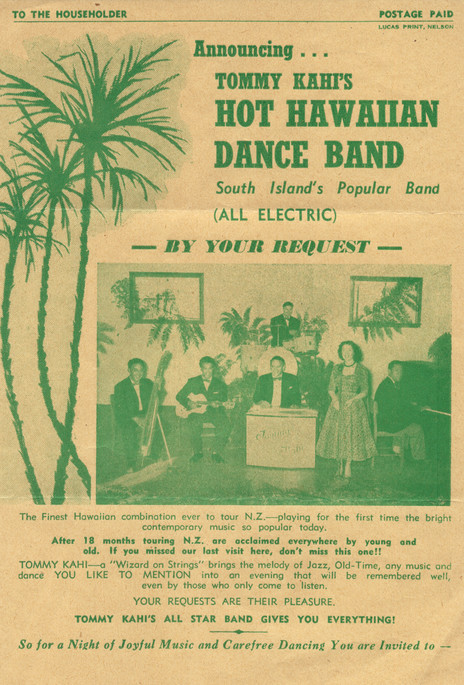

“I’d play Hawaiian, it was very popular. I never ever copied anything. I used to arrange the music how I thought it should be. And I’d do that for all the stuff. Jazz mainly, and some Hawaiian stuff when I wanted to cool the crowd down, calms them right now. Then when I wanted to hot it up, I’d play jazz.”

Tommy and his band used to rehearse at the Pacific Buildings, a musical hub on the corner of Queen and Victoria Streets. In the 1950s the building also contained Stebbing’s studio, Mascot, the Musicians Union, and Southern Music publishers.

“We used to come out of there and go to The Civic and catch a taxi. We’d stand and wait – and every single sound, cars screeching, horns ... I had perfect pitch and I’d say Ab, Eb ... [I] had perfect pitch in those days. That’s how I used to be, I trained my ear to every mortal sound. Every mortal sound was a note. A good musician has a good ear, and I trained my ear for that. I put that down to when I was a kid first starting, listening to the radio, listening to chord changes.”

“I trained my ear to every mortal sound. Every mortal sound was a note.”

As the entertainment world gathered pace after the war, Tommy found work on the Tivoli Circuit, a vaudeville-style revue that would tour theatres across Australia and New Zealand.

His first foray across the Tasman was in 1946. “It was a hell of a trip, rough, three days on the Mariposa. I was seasick. I had a good friend in the band who was sax player, Jimmy Johnson. He and I were always together. When I worked in pit, I’d play guitar, blow a bit of trumpet, bang a bell or blow a whistle, whatever was required by the score. You learn to do all these types of things when you’re in a show band.

“There used to be eight Kiwis. Well that first year, the Australian union says no way, it has to be eight Australians, only two New Zealanders. I said, ‘look mate, you do that to us, and we’ll do the same to you when you bring a show from Australia to our country.

“I was just an ordinary guy, but I knew all the guys like [union leader] Tom Skinner, who was great, and Bert Peterson used to be president of the Musicians Union.

“I think a show was coming over with 11 Aussies in it. So Tom says ‘right’; Bert says, ‘if they do that to you they won’t be able to play.’ They had to scrub it.”

Tommy says there were often disputes with bandleaders and promoters about payment. “The going rate in those days for a showband pit orchestra was 12/6 a night each. You never made anything out of playing shows.”

There was money in promotion though, and Tommy used his Tivoli experience to good effect, organising Round the Town talent quests which toured the country. Christchurch saxophonist Stu Buchanan recalled it was good work. “He could take a band right around the North Island and he would fill the halls, everybody would get paid and everybody would do well.”

There was also money to be made in the Astor studio in Shortland Street, where Noel Peach recorded acts for his Tanza label as well as producing radio jingles.

“We used to get 22/6 (22 shillings and sixpence) for a jingle – not good money – Nancy Harrie, George Campbell playing on them, making them up as we were going along. I did PK Chewing Gum and Andrews Liver Salts.”

He claimed to have discovered jazz singer Mavis Rivers.

“She was a Mormon and I had to do this job for the church. While the Mormon choir was [singing], she had this one bar and I thought ‘gee what a voice.’ I went back and said ‘I’m having a jazz show tonight, would you sing?’

“I introduced her to Noel Peach for a lot of jingles. I took her in with a radio band, got her started.”

Of the female singers around Auckland at that time, a roster that also included Esme Stephens and Pat McMinn, he rated Rivers the best. “Yet there was only one that made [a hit], Pat McMinn. That’s the difference, if you’re lucky in a certain thing. Crombie Murdoch and Pat did ‘Opo’ about Opo the dolphin in Opononi, my home town. Bang! Success! Sold thousands. Yet someone else like Mavis could do ‘How High the Moon’ and all those jazz things, didn’t do a thing. That’s where it can be so disheartening for some musicians.”

He remembered a session for Nelson-born, Australia-based country star Tex Morton. The contract was for a session at the Astor Studio in Shortland St, 8am to 5pm. “We signed it, George Campbell, myself, we backed this … got through the first number. The next day we’re there at 8am and he rolls in at 1pm, drunk. Well I grabbed him and said, ‘we’ve been sitting here all day waiting for you. You do that once more and I’ll [thump] you.’ ‘Alright, okay Tom.’ All set next day and he rolls in at 11am. I said to Noel, ‘either he pays us now or otherwise no dice.’ So the boys agree with me, he had to pay us on the spot. So then he had to turn up and finish his records.”

Kahi said, “either Tex Morton pays us now or otherwise no dice.”

According to Praguefrank’s discography, Morton had as many as five sessions in Auckland in 1949 and 1950. The results, including ‘The Stockman’s Prayer’, ‘A Soldier’s Sweetheart’ and ‘He Holds the Candle while Mother Chops the Wood’, were released as 78s on the Tasman label in New Zealand, and on Rodeo in Australia.

While the sessions included Morton’s touring band, the discography says on some of the Auckland sessions he was accompanied by steel guitarist Will Jeffs (Bill Sevesi, replacing Tommy) and other local musicians led by drummer Wally Ransom.

Tommy says at the end of that session, he took the fee and headed for Christchurch, which he had taken a liking to during his tours around the country, and where he established a regular Saturday dance at the North Beach Memorial Hall in New Brighton, billed as Tommy Kahi and his Hawaiian Rhythmaires.

“I liked the town of Christchurch and I liked the people and I adopted the place,” he said.

It was there he met his future wife Rosemary O’Connor around 1952. “I advertised for about three months for a singer. I had blokes and women who were shocking. And my bass player George says, ‘Tom, there’s a girl who’s started to sing like Rosemary Clooney. She’s from Glasgow, with red hair.’ She came down, I said ‘they tell me you can sing.’ ‘Oh I sing a bit.’ She sang ‘Half as Much’. I heard her voice, she’s tremendous. Technicians in stations love Rosemary’s singing because she possesses a vibrato that’s absolutely perfect. And then she’s scared stiff, shaking like a leaf. Yet when the voice comes out it’s absolutely perfect.”

O’Connor became a regular on Christchurch radio, and she also sang for Nick Nicholson’s Neketini Brass. There’s a 1956 recording on Tanza with O’Connor backed by Tommy Kahi’s Polynesians singing ‘Leahua’ and ‘I’ll See You in Hawaii’. It’s likely the Polynesians were Bill Wolfgramm’s Islanders, with Tommy’s teenage bandmate John Bradfield on guitar. Wolfgramm, the Tongan steel guitar maestro, is credited for O’Connor’s first Tanza release, ‘South Sea Island Magic’ and L’ittle Hula Heaven’.

The couple bought a house on Marine Parade and Tommy rented a studio on Manchester Street where he taught for about 30 years, before handing the business on to younger brother Mark.

“I taught Kevin Bayley, Billy Karaitiana. They learnt quicker if you taught them in a group,” he says.

Other notable students included singer Brent Brodie and Jenny Blackadder, New Zealand’s “queen of the banjo”.

Karaitiana told the RNZ Musical Chairs programme he started playing ukulele in a band with his father and uncles, who liked Hawaiian and swing music as well as popular Māori tunes.

“I was about seven or eight. It was in the early 1950s. One day Tommy Kahi came to my dad – he’d had an argument with his brother just before a three-week tour of the South Island by Tommy’s Hawaiian Serenaders. Could he take me on the road? Dad said, ‘he doesn’t play bass.’ Tommy said ‘I’ll teach him.’ So he taught me a couple of positions and he said, ‘now you know everything! If you get lost, go on the top string, nobody else knows – and that’s been the philosophy all the way along.

“It was a positive start. He was a good teacher of young kids.”

Another young musician to come across Tommy was jazz pianist Mike Nock, when he was a schoolboy in Nelson. Tommy’s version was that he used Nock for a 21st birthday party gig.

“He thought he was good. He was, his arpeggios were good but his right hand was faster than his left hand. At the end of the show he says, ‘what’d you think?’

“I said, ‘you’re bloody awful.’ He says, ‘what’d I do wrong?’

Kahi said to Mike Nock, “you’re bloody awful. He says, ‘what’d I do wrong?’”

“I got on the piano and banged out some chords. I said, ‘That hand’s slow, that hand’s too fast. Now – hop on the piano.’ ‘Cherokee’ was the number. I’ll never forget, beautiful piece of music, so many key changes. I got stuck in, thumped the heck out of him for about an hour. The sweat was pouring off him, but he gradually got better.”

Nock remembers it as a jam session in Motueka around about 1955 Kahi’s Hawaiians were in town playing dances for the tobacco pickers. “Tangi Williams on guitar, probably Keith Wright on drums, Bert Penney was playing bass. They had decided they were tired of playing all this Hawaiian music and they wanted to play some jazz and we had a little jam session at Mead Manifold’s house.”

The other band members were impressed enough by Nock they stayed in touch. When they jumped ship from Tommy they invited him to join their new band, The Fabulous Flamingoes, which ended up becoming part of Johnny Cooper’s travelling circus.

Tommy claimed to have introduced rock’n’roll to Christchurch, transcribing ‘Rock Around the Clock’ and ‘See You Later Alligator’ from shortwave radio.

But he described the highlight of his musical career as the night he was asked by conductor John Hopkins to sit in with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. “He shows me the score, I say ‘yeah alright.’ Well I was shaking like a leaf, the music in front of me. He counted me in, and I started playing this steel guitar with 100 musicians behind me. What a sound. It was beautiful. If only there was a tape recorder then. All the blokes afterwards stood up and gave a clap. I was so proud. Playing steel guitar you get all the tone from the tips of your fingers, not from the instrument, the amplifier or the pickup, but from your fingers.”

the highlight of Kahi’s musical career was when he was asked to sit in with the NZSO

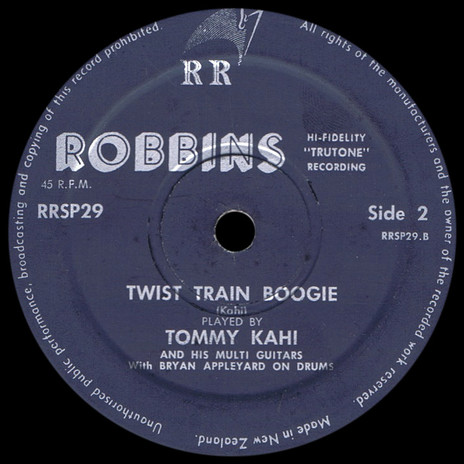

Tommy’s interest in classical music can be heard on his 1963 release ‘Bumble Bee Boogie’ on the small Christchurch’ label Robbins. It’s a frantic multitracked version of the Rimsky-Korsakov composition ‘Flight of the Bumble Bee’, with drummer Bryan Appleyard laying down a beat accompaniment.

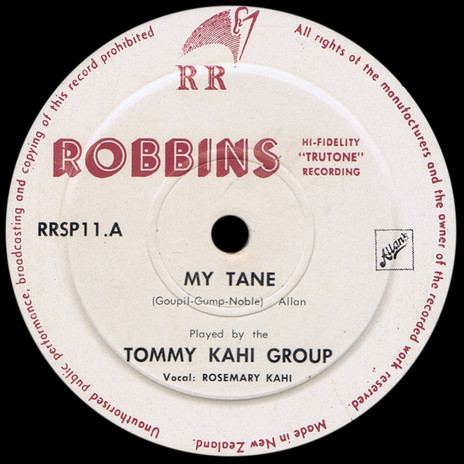

Also on Robbins is ‘My Tane’, with wife Rosemary on vocals, and the couple duetting on ‘Goodnight Aloha’ on the flipside.

As well as teaching, Tommy continued to organise concerts around the South Island, including some years helping organise the entertainment at clubs attached to the Operation Deep Freeze headquarters.

He says his charity concerts helped build at least five kindergartens and three scout halls, as well as a swimming pool at Ross.

In his 60s Tommy’s health started to fail, with a series of strokes taking him off the bandstand – but not before he held a sold out farewell concert on 23 June 1996 in the familiar surrounds of the New Brighton Bowling Club.

Tommy Kahi died less than a month later on 18 July 1996.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air