The 1983 New Zealand Music Awards had several Māori or Polynesian nominees representing the entertaining talent of a people who are taken for granted as natural entertainers, both home and abroad. The names go on and on: Inia Te Wiata, Kiri Te Kanawa, Howard Morrison Quartet, John Rowles, Māori Hi-Five, Golden Harvest, Billy T James, Herbs and a host of others.

Many artists are more well-known overseas on the Asian or Pacific entertainment circuit than they are at home. That’s because it’s possible to make a good living from entertaining overseas.

But what have these Māori and Polynesian artists got that makes their sound distinctive? That’s a question that’s being taken very seriously by some music people. Is it more than brown-skinned Pacific people playing and singing funk, soul, reggae, blues and disco by black American artists?

One of the people looking for the contemporary sound of young Polynesia is Maui Prime, or Dalvanius as he’s professionally known. He’s been on the lookout for some 10 years of his professional singing career and he says he’s close to the source of the sound now.

Dalvanius Maui Prime, Tu Tangata, December 1983

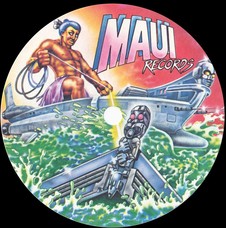

He’s launched a new record label, Maui Records, as the waka to carry the sound of young Polynesia into the next century. And with his first record release on his label, he’s chosen to turn the Māori world on its ear by recording the 1983 Polynesian Festival winning poi song ‘Poi E’ with a strong disco accompaniment. That’s the sound of the Pātea Māori Club complete with poi, backed by the driving sound of top session musicians.

To date it’s selling well around New Zealand despite the rather limited airplay the record is getting, mainly on the Tonight Show [on RNZ’s ZB Network]. The problem is one that all music different from the norm has: it’s unprogrammable. That is, it doesn’t fit in the nice and simple formats that New Zealand radio stations and television have for music.

For one thing, it’s not in English and for another, it’s not the traditional sound of the poi, what with the loud, brash disco beat.

These are the problems that Maui Prime believes we have to look at as a nation if we are to discover what makes the indigenous people of the Pacific distinctive in their sound. Perhaps it’s a Pacific Motown sound.

Firstly, let’s look at the credentials of the man who’s making sound waves. Maui went to Australia some 10 years back, and with sisters, Cissy and Barletta, became known as Dalvanius and the Fascinations. Their style was labelled as “sepia soul”, and they soon established a large following.

Maui: “The music scene is much more geared up there to provide support and work for entertainers, from protection on copyright for songs to professionally managed club circuits.”

Dalvanius and the Fascinations performed at the opening of the Sydney Opera House and over the years have sung in concert with such greats as Issac Hayes, Dionne Warwick, The Commodores, The Pointer Sisters, Osibisa, Ike and Tina Turner, Petula Clark, and Eartha Kitt.

Dalvanius (at right, in fedora) with members of NZ band Collision and the Commodores, Tu Tangata, December 1983

They signed to Reprise Records in 1974 and then moved on to Festival. It was here that Maui met a man who was to leave a big impression: Roger Davies, the manager of the Australian group, Sherbert.

Maui: “He told me to go for a Māori/Pacific sound and leave the soul/cabaret. He said we’d never get anywhere without an ethnic sound, that came from our background.”

That sort of remark posed a few problems for Maui, as he now readily admits. At that time he wasn’t quite sure what his ethnic background had qualified him to sing about on the music circuits of Australasia.

The trio went back to singing funky rhythmic songs like a political spoof ‘Canberra, We’re Watching You’ and mega-pop shows like Countdown on the ABC television network.

Dalvanius with the Pointer Sisters, April 1981. From Tu Tangata, December 1983

Maui: “We were starting to do original material and began doing background vocal and session work for other artists’ recordings, people like Richard Clapton, Renee Geyer. I became really interested in record production and what could be done to improve a sound.”

In 1976 Maui returned to New Zealand to find the sound he wanted. He found a Māori band, Collision, and returned to tour Australia with the African band, Osibisa.

“They had such a power influx of black music, in their instruments and language which they really showed. They looked at us and said, why can’t you do the same? You know, fuse your culture with your music.”

Feau Halatau receives Best Polynesian Record from Wiremu Kerekere as Feau's wife looks on. Tu Tangata, December 1983

This time Maui came up against lack of knowledge of the Māori language, plus the problem that Māori culture didn’t seem to have the percussion tradition that the African had. Also around this time, Maui’s brother in Angola wrote to him telling about a fantastic black African stage show called lpi Tombi.

In 1978 Dalvanius and the Fascinations recorded ‘Checkmate on Love’, a slow ballad that won many awards at the Australian Soul Awards.

In 1979 Maui returned home to his dying mother and was confronted with his Māoritanga. He couldn’t understand the Māori his mother spoke in her last days. From this he vowed to feed the spiritual man and not just the physical man.

A year later, Dalvanius and Barletta, minus Cissy, toured marae and worked with kids. They did a New Zealand tour with the Pointer Sisters and the old question came up again, what’s the Māori sound?

“The sisters asked a lot about the Māori people, what they had and what was behind the culture. To them it wasn’t obvious by touring the hotels of New Zealand. They turned on the radio and said they could be back in the States listening to the same music. I went out and bought them tapes by Herbs, St Joseph’s Māori Girls Choir, [Dave McArtney and] the Pink Flamingos.

“We got a chance at the Mormon College at Hamilton to give them a pōwhiri. It was great, I stumbled through a mihi and for their waiata they sang ‘He’s So Shy’. They said the music reminded them of gospel churches back home.”

After the Pointer Sisters left, it was obvious some soul searching was in order, but it took a further input from overseas in the shape of Fleetwood Mac’s Christine McVie. “She watched our act and advised us to get ethnic.”

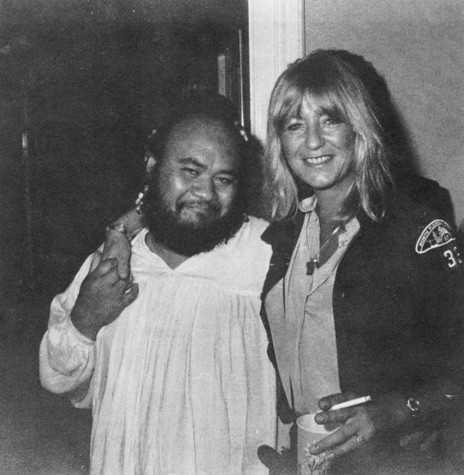

"Get ethnic": Dalvanius with Christine McVie, Tu Tangata, December 1983

1982 saw both Maui and Barletta take an intensive Māori language course at Wellington Polytechnic. Maui has always loved the songs of Māori composers such as Tuini Ngāwai and wanted to meet her aunt, Ngoi Pēwhairangi.

“I was meant to be only staying a day or two in Tokomaru but it turned out to be several weeks. I found I had so much in affinity with Ngoi and we were able to write several songs, I would supply the melody and Ngoi, the Māori language. It was beautiful.”

From this fusion have come many songs to be recorded and the strengthening of the turangawaewae of Māori music.

“I had to look at the history of Māori recording in this country, and while there were many great artists and memorable songs, there wasn’t a base to develop from. Most of the songs were Māori words put to European melodies, so all royalties went out of the country. Recording companies recorded Māori artists on the cheap, and because the Māori artists were desperate to record, they compromised.

“Māori songs were recorded in the studio with just acoustic guitar backing a whole group, whereas most Pākehā arrangements had lush affairs with strings etc. People, including Māori, got to accepting that this was the Māori sound, the party style.

“Māori composers, myself included, never really considered the commercial potential of our music, and only now are realising how much has slipped through our fingers. It’s our fault that we have a lack of knowledge of the music industry because we never saw our songs as an industrial force. The royalties are immense from recording and performing original material. I object to the use of western tunes when there are young Māori songwriters today.

“The music I’m talking about is the contemporary sound for the rural and suburban Māori, it’s rhythmic and danceable, it’s for young people growing with the language. I steer clear of traditional waiata because no way do I have the spiritual mana of our tupuna when they wrote waiata. However, I see Ngoi and her songwriting as a link.”

Tim Finn backed by Herbs. Tu Tangata, December 1983

Maui’s response to a history of neglect of Māori music led him into the studio to produce an album for Prince Tui Teka. “I produced the album on the condition that he’d record six songs by Māori composers. He didn’t want to record ‘E Ipo’ because he’d done it before. After the mixing of the song, me and the engineer, David Hurley, cried, it was great. Of course it became a No.1 song in New Zealand, despite the limited airplay it got.”

Then to prove you don’t need lush arrangements for popular Māori music, Maui brought out ‘Māoris on 45’ by the Consorts. It was a sort of handclap and guitar sound of well-known Māori songs in a medley. It went to No.4. With these chart successes, Maui came up against getting airplay. A distinctive Māori sound composed and performed by Māoris proved too much for radio and television with their middle-of-the-road music and programming policy.

‘‘The Howard Morrisons, the Tui Tekas, the John Rowles will always be around, there’s a market for them and their middle-of-the-road music.

“We need Māori radio stations that are programmed according to our kaupapa, our take. We could learn from the Blacks of America who set up Black-owned radio stations and ethnic television channels funded by Black-owned companies.

“It’s pointless to expect specific airtime will be put aside for Māori music. In Australia, there’s ethnic radio and television. The minority cultures didn’t wait for government handouts, they went and did it. I’ve got plans on how to set up regional Māori radio stations around New Zealand and ways to fund it from Māori sources.”

After the airplay comes the marketing of the product and distribution. “We need total control of this from Māori composition to Māori recording producers and engineers, to Māori outlets. We’ve already had problems with Pākeha retailers who will order records by the DD Smash and other New Zealand bands rather than something by the Pātea Māori Club. They don’t relate to it.”

Joe Wylie's label for Dalvanius' Maui Records, 1983

How does Maui Records operate then to get over these hurdles? ‘‘Well, we work through the record company, WEA, who’ve given us complete control, because they’re sympathetic to our cause.

“They press and package and deliver to the record shops. We take the record around to the radio stations for programme directors to listen to. Usually we come up against the line, that market research has shown that listeners don’t want to listen to Māori music. I say back to them, how many Māoris or Polynesians did you survey? Even though ‘E Ipo’ was well known, it wasn’t played much on radio.

“Rock music programmes on television are even harder to crack. There’s Ready to Roll and Radio With Pictures which is programmed for a white middle-class audience. Herbs have been the only Polynesian band on RTR this year. One of our bands, Taste of Bounty, made it on Shazam! and have a RTR video for release soon

“Of course a release in the rock music field by a Māori club such as Pātea presents all sorts of problems for some television programmers. I mean is a poi song performed by an obviously Māori group with a disco beat acceptable stuff as contemporary music?”

Away from the razzamatazz of the recording world. Maui has met up with kaumatua who’ve encouraged him on his voyage, and other composers, musicians and singers. Maui is chairman of the steering committee of the Māori Composers Federation and it has received $12,000 from the Māori and South Pacific Arts Council to hold a hui in March next year on the Hoani Waititi Marae. Here it’ll look at the question of Māori music.

“Māori money is needed, not just grants and subsidies, but for investment in the Māori recording industry and performing arts to create vehicles. We’re aiming to have Independent Recording Industry awards. There are eight independent recording companies in New Zealand distributing and recording Māori and Polynesian artists, RCA, CBS, Ode, Warrior, Kiwi Pacific, Viking Seven Seas and now Maui Records.

“They would be the Aotearoa Waiata Awards, to recognise and celebrate the Polynesian sound. As well as different categories such as best song, best group, there’d be awards to technical people behind the scenes and a Māori lyrics section judged by native speakers. Judges of the music would be from America, Australia and New Zealand.

“is a poi song performed by an obviously Māori group with a disco beat acceptable stuff as contemporary music?”

“The awards would cover television and recording as well as concert material. Some sections would be open to public voting, the rest would be judged by the industry. We think this is the way to encourage talent that’s laying untaped at the present.”

As for Maui Records, it’s tapped the talent of four groups. Taste of Bounty, a Samoan family group who’ve released a four-track extended-play Party Time, have a great rock sound and songwriting ability, with tracks like ‘White Sandshoes’ and the title track. The Tama Renata Band and Ruinz have recorded. And the Pātea Māori Club should have another out soon.

Maui is planning to do a musical next year entitled Raukura as well as Whats Be Happen, a television show profiling Māori music and reviewing releases.

Sandwiched into this busy schedule is some personal homework for Maui. He’s attending a six-week long record producers course in Ohio, United States, that’s being run by people who have worked with all the top groups in the world. While in the States he’ll be boning up on the Black music industry with visits to Black radio stations and recording companies. On the way back he’ll stop off in Hawaii to take a course with composer Tommy Taurima, who runs an arts faculty there.

Whatever musically develops in the future, Maui Prime wants the Māori people and their cousins of the Pacific to have a share and say in it. The way he sees it is symbolised on his record label. Maui Records, like the ancestor Maui, is pulling Māoridom into the new world of today, Te Ao Maarama.

--

This article first appeared in Tu Tangata as “The Search for the Sound of Young Polynesia” in December 1983, and is republished with the permission of Te Puni Kōkiri. The images are originally from the collection of Dalvanius Maui Prime.