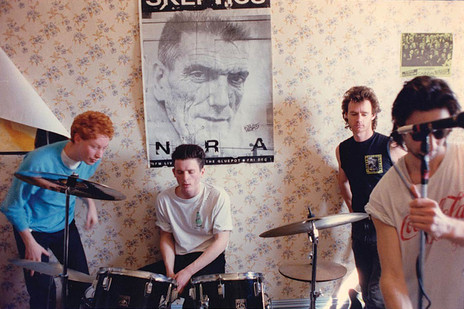

By 1982, and now 16, his three-piece band Company was organising gigs in a Lynfield community hall. Unable to figure out covers – although the group did manage a version of ‘Super Freak’ – Fleming set to writing originals.

When school ended, his mates got jobs while he went to the University of Auckland, and everyone lost touch.

Suburban life made way for boho madness when he moved into rooms above the now-demolished Bridgeway Tavern on Hobson St: “My mate Peter was bartender. It opened at 7am and was popular with Russian sailors. We lived upstairs and sometimes had gang guys coming up to break in. Yeah, it was great.”

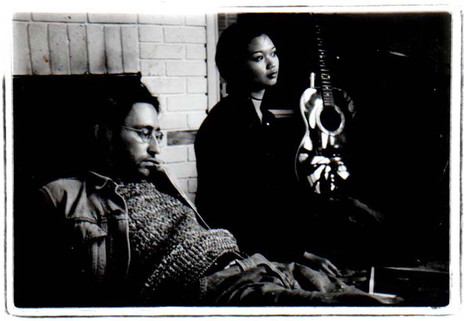

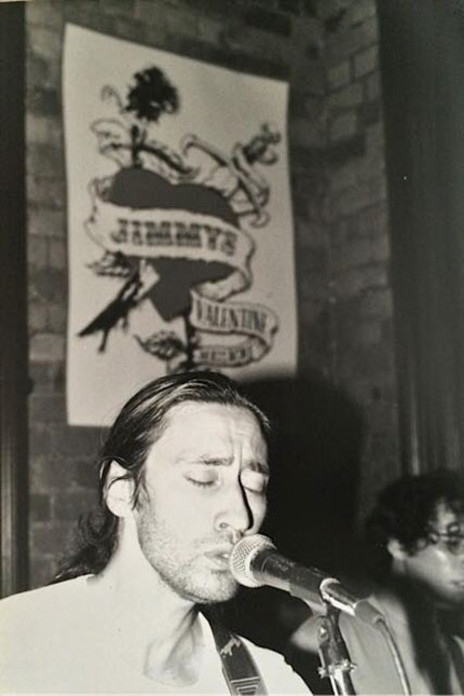

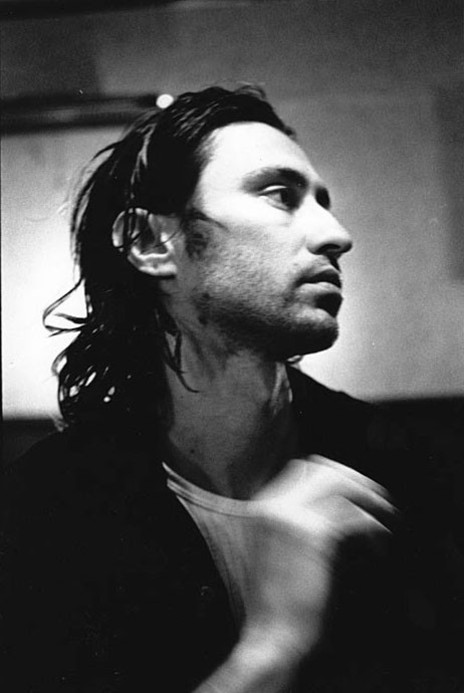

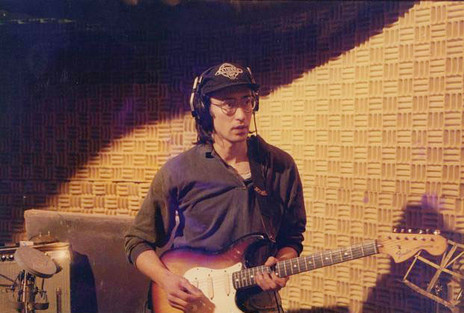

In 1989 and now finding lyrical inspiration in the gritty melodramas of urban life he began playing “bloody awful” solo shows at university venue Shadows, while recording at student radio station bFM, including his first acoustic run at ‘Codeine Road’. He met two guys also hanging at the radio station, bassist Nick Kreisler and drummer Stuart Broughton, and after bonding over their favourite American artists (Springsteen, Reed, Dylan and Television) they began jamming at Kreisler’s flat. Kreisler also provided their name, Greg Fleming and the Trains.

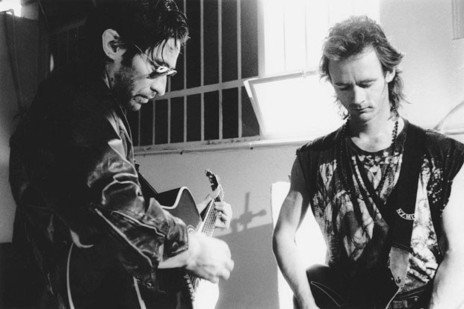

Their search for a second guitarist ended when Mark Petersen turned up to a party at Fleming’s Ponsonby flat. Fleming had seen him play and liked what he’d heard. By the end of the night Petersen was on board. “He really upped our game,” says Fleming, “he’s a fantastic guitarist.”

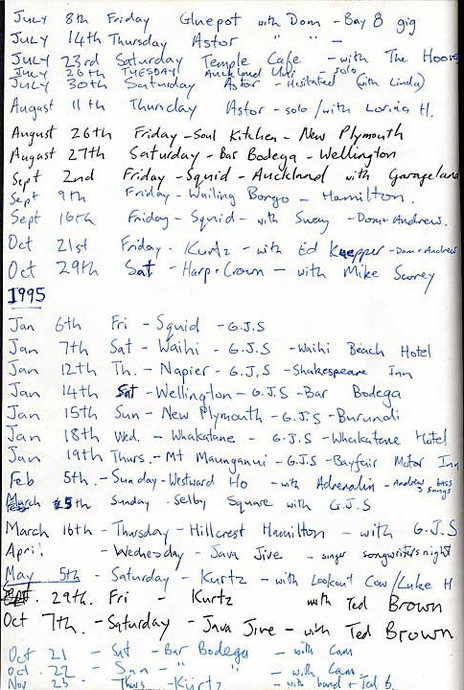

The band was now gigging hard, it helped that Broughton ran the Dog Club (The Dog’s Bollix) on Newton Rd. He also managed Supergroove, so they took a lot of support spots. Otherwise they played any gig going, with acts as diverse as Graham Brazier and Darren Watson’s Chicago Smokeshop, to Hallelujah Picassos and The Malchicks.

“I was only 28,” says Fleming, “and like any kid that age I thought ‘wow, I’m gonna be a rock star. Let’s do this.’”

But despite their harder edge, bFM airplay, and interest from Trevor Reekie’s Pagan label, The Trains’ urban-country struggled for purchase in Auckland’s alt-rock scene.

“Ha, I didn’t fit in at all. I wasn’t the Pixies you know. I’ve always been a bit out of step, I have my own way, but it’s too ‘alt’ for the rock-pop mainstream, the Dave Dobbyns and all that, and too straight for the bFM crowd. It was always that, and still is.

Things were looking up when they were signed to Deepgrooves subsidiary label Lost, which was looking to expand into rock.

“But when I look back at that early stuff, they’re all strong songs. Whether the production was right is something else.”

Things were looking up when they were signed by Kane Massey's Deepgrooves (via a subsidiary label, Lost) which was looking to expand into rock after building a reputation built around dance-oriented urban artists.

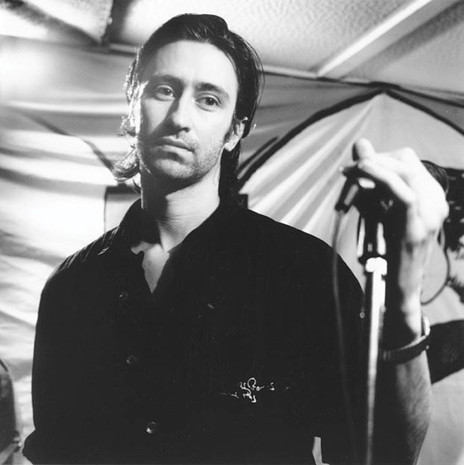

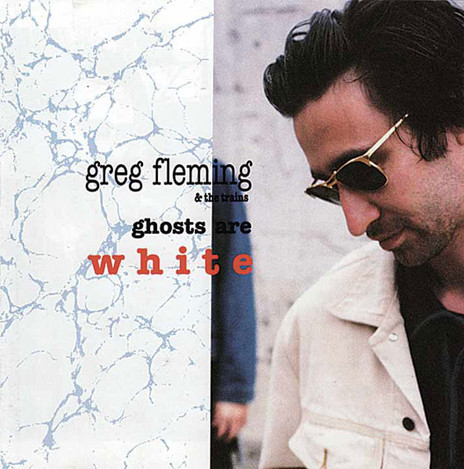

Now armed with a budget, Greg Fleming and the Trains went into The Lab Recording Studio on Symonds St in 1991 (with Matthew Heine producing) to record their debut album, Ghosts are White. Sessions were sporadic and the project stretched out to 1993.

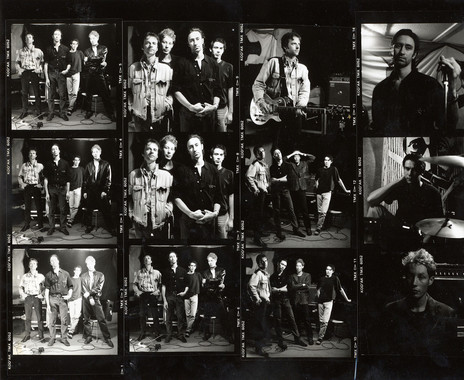

The line-up became fluid with both Broughton and Petersen leaving in 1992, the latter to become the full-time replacement for Andrew Brough in Straitjacket Fits, having toured Australia with them the previous year. In their place came drummer Robert Key (They Were Expendable, The Expendables, The Cakekitchen) and guitarist John Segovia (Axel Grinders, Shaft, Billy Joe Shaver).

Key’s stint was brief and he was soon replaced by Ricky McShane (Chainsaw Masochists), a change that prompted Kreisler to leave in June 1993. Keen to push his own songs, he formed the Pet Rocks.

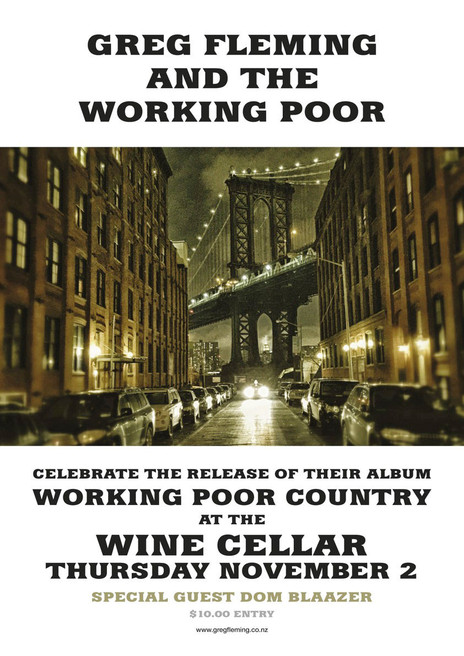

In came bass player Cameron Miller and Fleming’s old friend, keyboard player Dominic Blaazer, a prolific musician who has played with acts such as Peter Stuyvesant Hitlist and Smoothy as well as guesting with everyone from David Kilgour to the Topp Twins.

Ghosts Are White was released in 1993 with two supporting videos, one for the title track (and official single) which was also the debut effort of future filmmaker Jonathan King, the other a Simon Raby-filmed clip for ‘Mr Clive’.

In 1994 Miller left for the UK and in came Andrew B White, who had been doing design work for Deepgrooves and other labels.

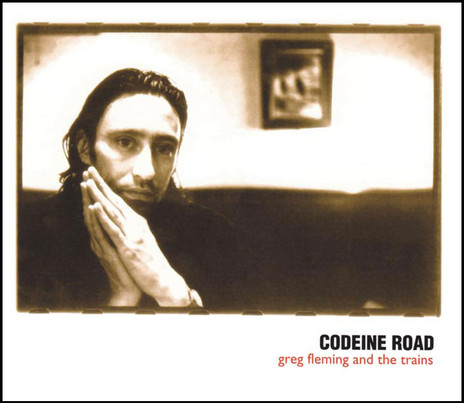

In May 1994 a lush remix of ‘Codeine Road’ by Anthony Ioasa (Grace) was released. The accompanying video, shot on Auckland’s Karangahape Rd by Bruce Sheridan, attracted considerable attention and it seemed like Fleming’s time might finally have come.

The band was now touring the North Island and was offered support acts for Sheryl Crow and Counting Crows only for both to fall through at the last minute.

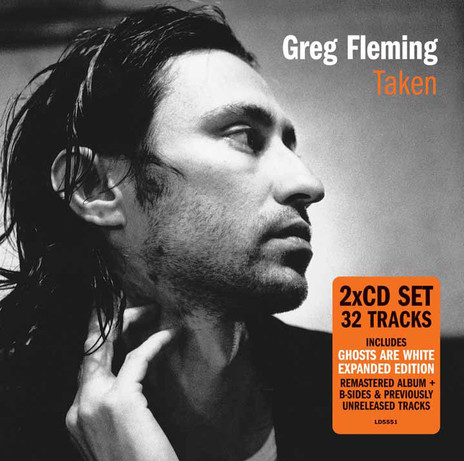

No matter, with momentum building the band went into York Street studio with producer-drummer Wayne Bell and new guitarist Andrew Thorne to record their ambitious follow-up, Taken. However the completed work was shelved indefinitely when Deepgrooves collapsed. Fortunately, Fleming managed to grab a CD copy of the final master.

It was a huge, personal blow and in 1995 Fleming walked away from music completely: “I just didn’t seem to have a career after that. It was probably my own fault, I was just so pissed off.”

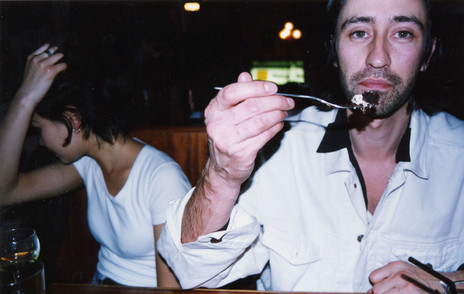

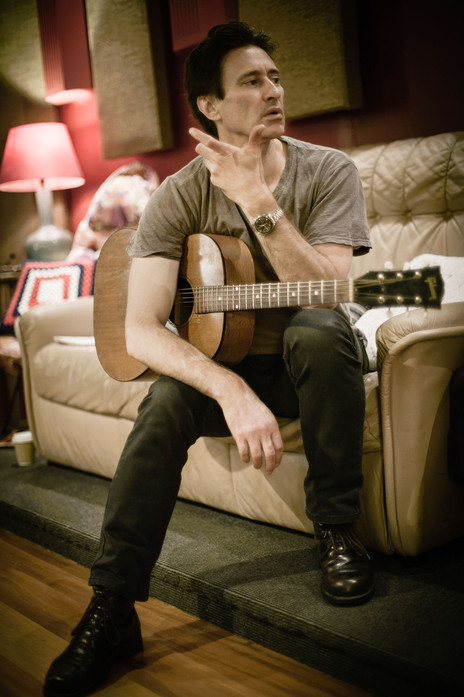

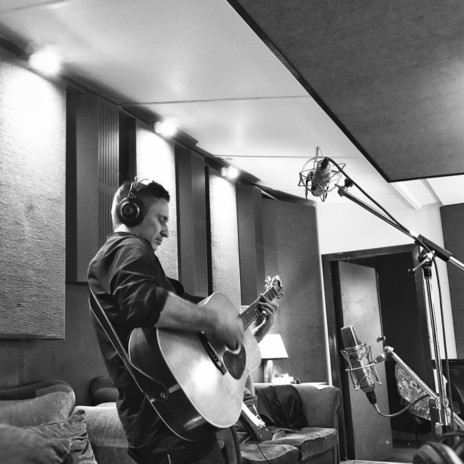

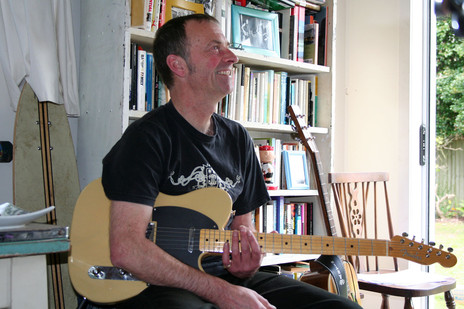

And he stayed that way until 2010 when, out of the blue, White called to suggest he release Taken on his label, Luca Discs, using Fleming’s CD copy. Then it was “let’s do another album” and with White’s backing the line-up of Fleming, Segovia, White, Blaazer and drummer Earl Robertson (The Chills, Upper Hutt Posse, Peter Stuyvesant Hitlist) went into Roundhead Studio to record Edge Of The City.

Internet mogul Kim Dot Com was recording his own album there at the same time and began hiring White’s analogue synthesisers with the proceeds going into the album fund.

Then, in 2012, White, who had become the band’s driving force, left for New York. What now?

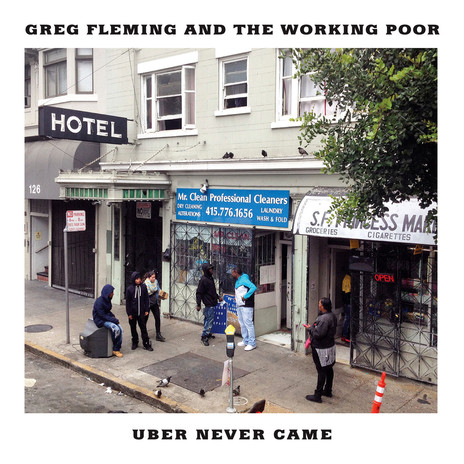

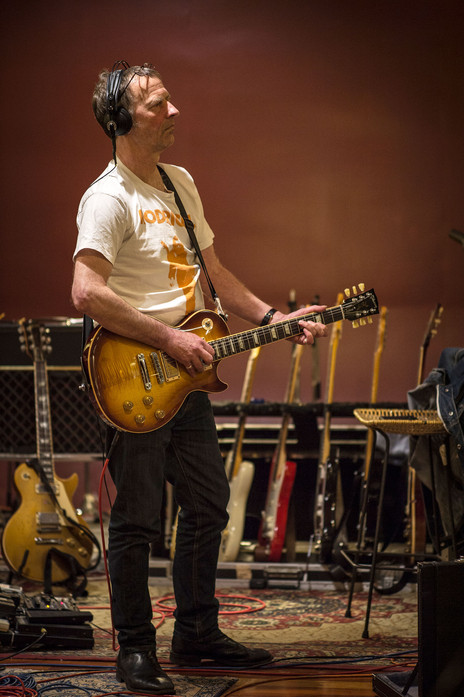

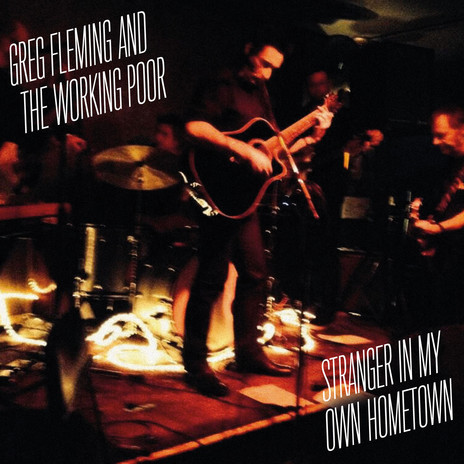

“[Greg] just called me out of the blue,” says Wayne Bell, “we’d had no contact for years. I think he’d enjoyed the process of us working together and he asked me to come steer the ship a bit and produce his next record [Forget the Past]. I said I would, but would he be okay with me putting together a band, collectively, with his input, but a whole new thing. That became the Working Poor and we’ve had the same line-up to this day.”

The new band comprised Fleming, Segovia and Thorne with Wayne Bell (drums), Nick Duirs (keyboards), and Mark Hughes (bass).

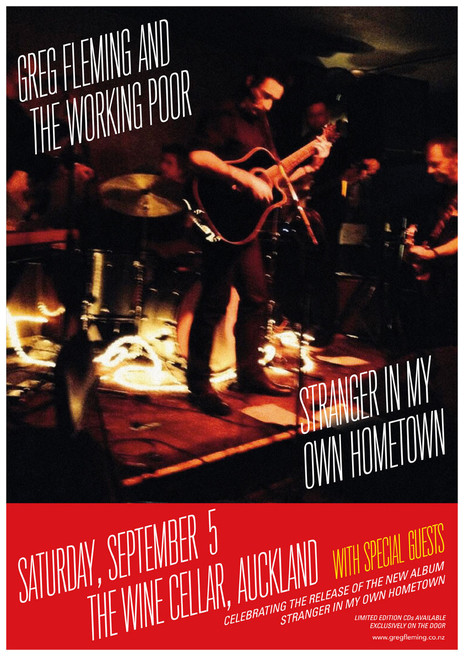

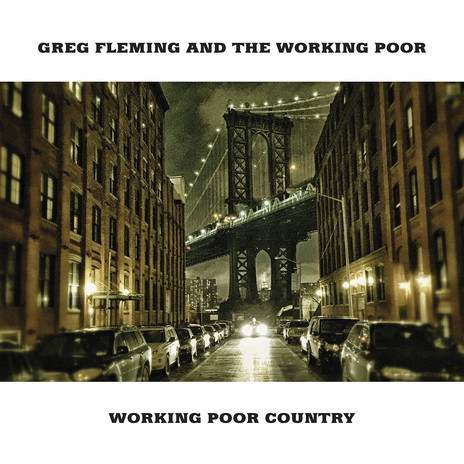

Greg Fleming and the Working Poor have now released five albums which usurp the traditional trappings of country rock.

Says Fleming: “I’ve somehow ended up with this band that, if I wasn’t in them, I’d go and see them play. They are amazing.”

Greg Fleming and the Working Poor have now released five albums which usurp the traditional trappings of country rock by including various instrumental experiments. Fleming, you see, is a fan of hip hop.

“I keep saying I want to make a hip hop record, like seriously, because I can’t do hip hop which I think is quite interesting. It’s like, can I have an honest attempt? Take a song like ‘Jaywalkers’ (off Forget the Past) which is all drum machines and ‘Move To The Side’ (off Working Poor Country) which uses drum and piano loops, I already love mixing stuff up.

“We do try that sort of thing, but with the Working Poor, once we start playing it always starts sounding like the Working Poor. It’s us.”

“For me,” says Bell, “you can tell when a song’s good when it just plays itself. You’re never searching for things to put into songs, and that’s how it is with Greg. We always get to a point where the best approach is to start taking stuff away and get out of the way of the story.

“But he’s never really got his dues and I think that’s because he polarises people. He’s not a classic singer, but in terms of songwriting I rate him up there with not just New Zealand’s iconic writers but with people like Steve Earle, that’s the world he lives in.

“We lose money on every album we release, but the process of recording is the most enjoyable thing in the world. We ask ourselves, every time, is anyone going to buy it? Is anyone going to hear it? Who knows, but if not, that’s still not a reason to not record. These songs need to be documented.”

So it’s a shame success isn’t measured by productivity because the songs continue to pour out of Fleming: “That’s when I feel happiest I guess, that period when a song is on the boil,” he says. “I have to capture it quickly, record it on a dictaphone and that’s my blueprint. Then I’ll take it to the band [The Working Poor], but I don’t give them the recording, I just start playing and we mould it together.

“My problem always is that once that’s done I lose interest in it immediately: okay, what’s next? That’s why we don’t over-rehearse and almost never go back to old songs.”