In scene one, a small bearded man is leaning forward in a darkened room lined with shelves stuffed with records, backing up his implied authority. In a quiet voice that is both intimate and seductive, he slowly but surely outlines the central premise of a cultural manifesto that endures to this day.

His name is Roy Colbert and he is speaking in late 1982 to the influential television music show, Radio With Pictures, for their year-end round up of the resurgent New Zealand music scene in a segment cleverly named “Friends of The Enemy”. The title is a reference to the influence of Dunedin punk group, The Enemy, who moved to Auckland in 1978, and evolved into new wave chart group Toy Love.

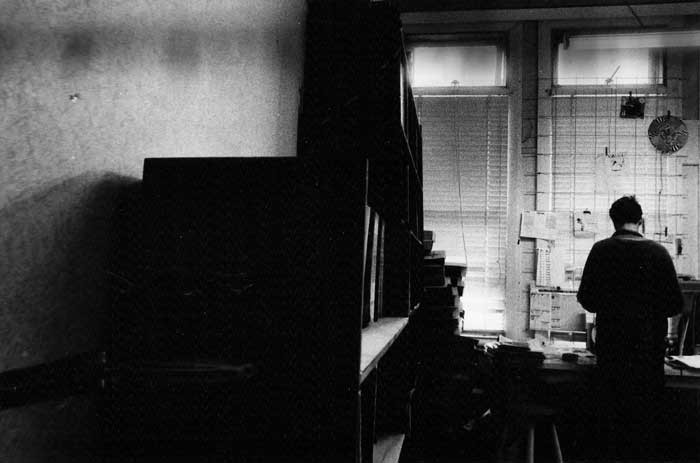

Records Records - Roy Colbert's record store, with Roy outside

Colbert is the owner of Records Records, a small second-hand record store that sits above the Octagon in central city Dunedin. He is a 1960s-era survivor and sometime feature writer and music columnist for Dunedin newspapers, RipItUp and The Listener.

This is what he says.

“If you’ve got good songs, that’s the most important thing, and that’s what all the Dunedin bands have concentrated on. They may not be great musicians, but they’ve all written good songs and they’ve got up on stage. They haven’t dressed up. They haven’t added a bit of Duran Duran or a bit of ska or whatever maybe they should have added, but have just written good songs and got up and done the songs and Dunedin audiences have reacted to the songs.”

There, in a nutshell, are the central tenets of the “Dunedin Sound” and its related style – good original songs played by amateurish musicians to small local audiences without regard to popularity, current musical style, or fashion. It is a selective co-option of the ethos of punk and post-punk culture and a broad echo of elements of an older construction of New Zealand national identity.

In scene two, Chris Knox, singer for Toy Love, and, more recently, Tall Dwarfs, a central figure in Flying Nun Records, the Christchurch-based independent record label founded by punk fan and record shop manager Roger Shepherd, sits in a similarly darkened room outlining the musical method and antecedents of the “Dunedin Sound”.

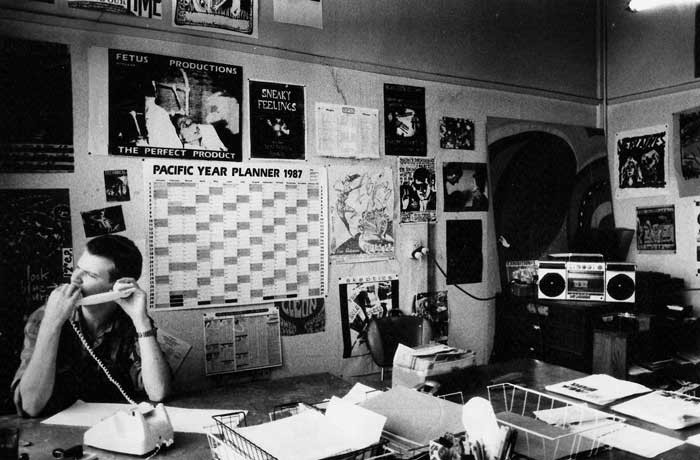

Roger Shepherd in the Flying Nun office, Dominion Building, Christchurch, 1985

“The new bands in Dunedin use open chords. They don’t put their fingers right over for barre chords. They let the strings resonate which leaves you with the impression that one guitarist is three, which is basically a legacy from The Clean through The Velvet Underground or vice versa. The other half of them are mostly influenced by sixties bands like Love and The Beatles.”

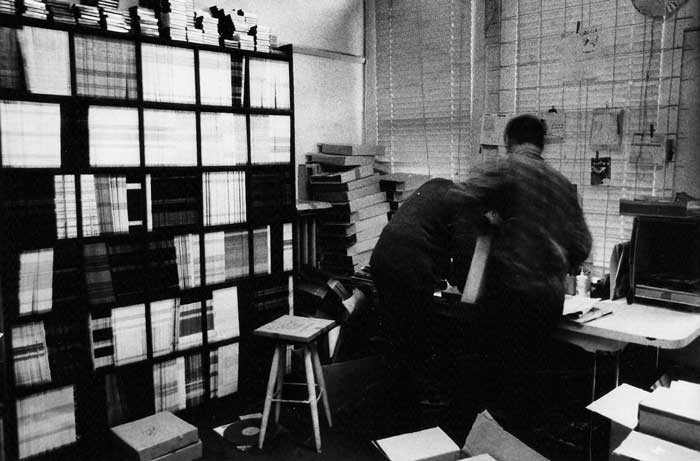

The Clean's Hamish Kilgour in the Flying Nun offices, Christchurch, c.1982/3 unpacking Boodle EPs

Roy Colbert elaborates. “It’s interesting that the leading figures in all of the better bands are all great record freaks.”

Roy Colbert elaborates. “It’s interesting that the leading figures in all of the better bands are all great record freaks. They’ve all checked out all the major records that people have told them to check out and the influence really came from everywhere. There’s obviously the sixties thing. The Velvet Underground’s the most common one that’s thrown at the Dunedin bands, but there are so many other bands. You look at Graeme Downes of The Verlaines who’s got a lot of classical music in his upbringing, and Shayne Carter and Martin Phillipps, the Kilgour Brothers, Chris Knox; they’ve all got vast record interests. You hear anything from the Incredible String Band to Syd Barrett. There’s just everything in there. They’ve all been checked out.”

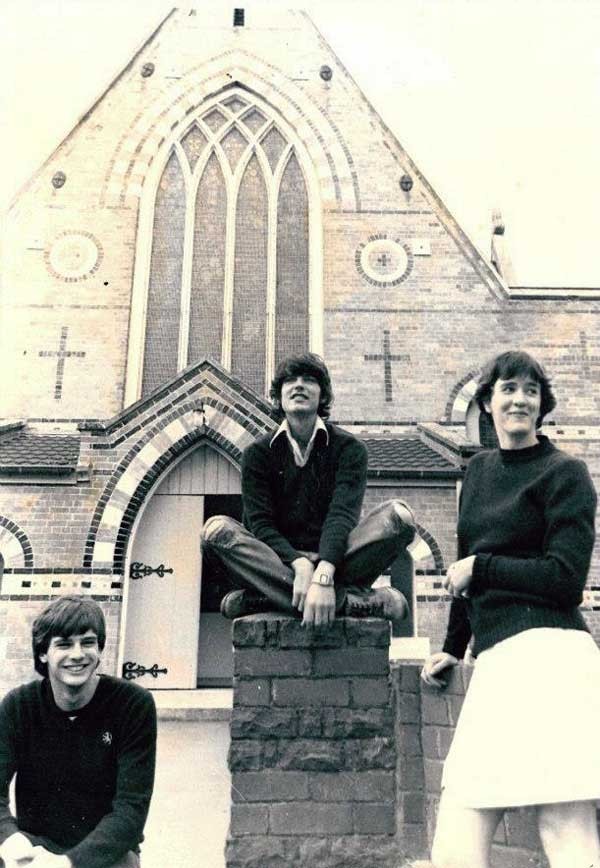

The Verlaines

The ethos of punk has now been connected to the influence of experimental and overlooked groups of the 1960s with a special caveat for The Beatles, who were both pop and experimental, uncoupling the Dunedin Sound from immediate influence. A vital step in establishing its perceived timelessness; a term the following interviewee will use.

In scene three, Martin Phillipps, the youthful guitarist, singer and songwriter of The Chills, which became one of the most successful of the Dunedin groups, is standing outside in crisp southern daylight. His dark hair is long for the time and almost mid-1960s in style. He's wearing a white button up collar shirt with regular patterns across it and answering a question posed by interviewer and fellow Dunedinite Brent Hansen about the supposed rivalry between the Dunedin and Auckland post-punk scenes.

He’s responding to the thoughts of Auckland musicians Michael O’Neill of The Screaming Meemees and Mark Bell of Blam Blam Blam, and Simon Grigg, who runs their Auckland-based indie label, Propeller Records. Both The Screaming Meemees and Blam Blam Blam had Top 20 chart hits with original songs using more immediate musical influences from the British post-punk movement.

Here we see another element central to the “knowing” of the era being formed. That of Dunedin’s difference, and Auckland’s “trendiness,” arrogance and distance. Having established a distinct musical lineage for Dunedin, New Zealand's post-punk community is now being divided geographically and culturally.

A group shot from the February 1984, Doug Hood promoted, Looney Tours Flying Nun touring show, with The Chills, Children's Hour, The Expendables and the Doublehappys, with tour manager Dave Merritt.

This carefully constructed version of New Zealand’s musical heritage will prove pervasive and enduring and be repeated almost exactly in John Dix’s pioneering 1988 New Zealand music history, Stranded In Paradise, forming the basis of many attempts to locate the “Dunedin Sound” and its importance.

In 1994, academic Tony Mitchell in “Flying In The Face Of Fashion – Independent Music In New Zealand – Part 1 – Pakeha Sounds” in North Meets South: Popular Music in Aotearoa/ New Zealand, the first published academic work examining New Zealand post-punk music will add another layer to the myth by trying to isolate “original” New Zealand music and the groups he thinks are creating it – the Dunedin Sound groups.

It’s a reductive interpretation that eliminates the vast majority of New Zealand groups writing, recording and releasing their own music, despite identifying correctly that there is a local reaction to every overseas music genre and movement.

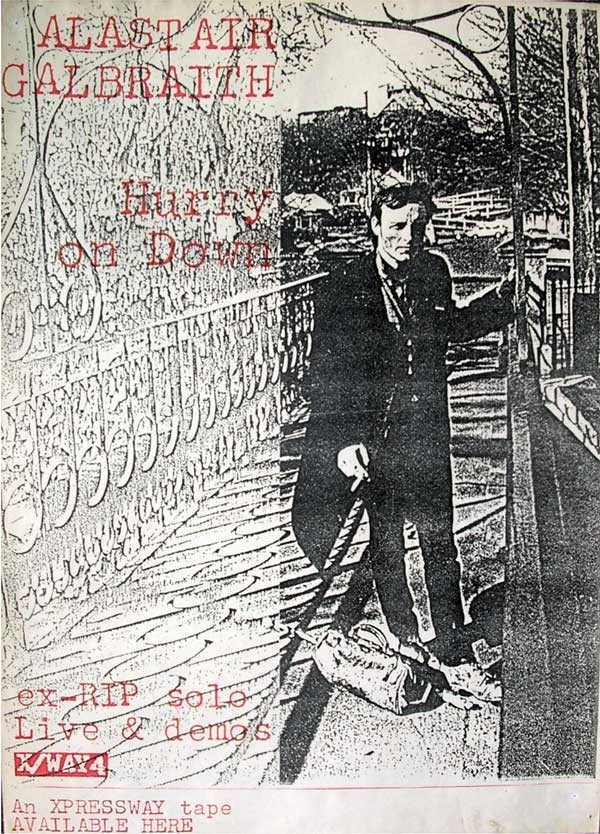

Most tellingly, he dismisses the acts associated with the Dunedin-based Xpressway Records as “internationalist,” producing “inward, obscurest, non-commercial sound scapes,” pointing out that the label had evolved to the point it no longer existed and was licensing or leaving its associated acts to sign to overseas labels.

To be true and “original” New Zealand music, Mitchell implies, it must not be related too immediately to overseas music movements, must be released on local record labels and have some chance of commercial, but not necessarily artistic, success.

For the Xpressway related musicians – many of whom have previously released their music on Flying Nun Records – there is no dividing line. This is simply another step on a life long creative trajectory.

In the same book, a close reading of Roy Shuker’s “Climbing The Rock: The New Zealand Music Industry” reveals the myth taking on an overt political will and dimension. Shuker’s political sympathies are clear as he makes the argument for government funding of “original” New Zealand music to balance up the “cultural imperialism” and "globalisation” of multi-national record companies, itself a reflection of the cultural nationalism prevalent in the 1990s.

The myth of the “Dunedin Sound” will be evoked as a constant in the years following, including a period where Dunedin musicians themselves reject its existence. Two recent books on New Zealand music, Grant Smithies’ Kiwi album appraisal collection, Soundtrack: 118 Great New Zealand Albums, which features many Dunedin groups, and Gareth Shute’s NZ Rock: 1987 – 2007, which has two chapters on Flying Nun Records related groups barely mention the term, pointing instead to the do-it-yourself (DIY) method of production, not a distinct sound, as the main connecting feature, or by subscribing uniqueness to an individual band.

Roger Shepherd

Despite reassessment, the myth will endure. As late as May 2009, Martin Aston, a British music journalist, who has published on Flying Nun Records groups in NME and New Zealand Herald, wrote in The Guardian “that geographical isolation was the salvation of New Zealand music” and “when anyone writes about New Zealand music they mean Flying Nun Records.”

Dennis Lim, in New York’s Village Voice in September 2001, talks about “a scene whose significance and romantic appeal had much to do with geographical isolation".

“Soaking up various Velvety sonics with heedless voracity,” he added, “the New Zealand sound percolated at a liberating remove from those very sources and happened upon its flushed, topsy-turvy energy as a result. The sheer distance traveled by these ornate yet ramshackle songs – wafting in all the way from Dunedin, a South Island town so remote it might as well be Antarctic – made them even more exotic.”

Relating perceived geographical isolation to cultural isolation enables the idea that a unique “folk” music has been created, a premise that will remain central to arguments claiming musical uniqueness for the “Dunedin Sound” groups.

The problem is Dunedin was never culturally isolated within New Zealand or the world.

The problem is Dunedin was never culturally isolated within New Zealand or the world. The cultural picture it received was proximate to the rest of New Zealand’s. It had the same record shops that were branches of English stores, who imported records.

An examination of the Complete New Zealand Record Catalogue of albums available to record shops in the early 1980s shows a wide and diverse array of sounds from reggae to dub to art rock to punk rock to soul amongst more mainstream sounds.

New Zealanders in the 1980s were big record consumers. In 1981 over 10 million records were purchased, rising to 14 million in 1984.

There was also plenty of internal cultural traffic within New Zealand. Dunedin was a university town that drew its staff from the western world and the rest of New Zealand, which also chipped in students from different locations all of whom had potential overseas contacts and conduits of information.

New Zealand music communities were interconnected through touring groups and other personal contact. Dunedin had access to the same TV shows and to the ZM network that Barry Jenkin broadcast his influential left-field music show on until December 1983. Jenkin was importing records directly from England as well as playing the new post-punk records being made locally.

Ian Dalziel in the Flying Nun office, The Dominion Building, The Square, Christchurch c.1985

Evoking (false) cultural isolation served three purposes. It increased the perceived uniqueness, originality and local inspiration of the endeavour – a process Simon Frith calls creating the “ideology of folk in rock” – and promotes what Thomas Schlereth describes as the fallacy that history is simple by showing only one version that violates historical truths and doesn’t show complex inter-relationships.

The idea of the “Dunedin Sound” fits this simplification. There are distinct edges to its community, sound and mindset that enable easy definition. It is conservative in its reaction to technology and the surge of youth fashion, which again creates distinct edges.

It has a strong fan base in the university communities who require intellectual validation for their artistic tastes that a form of “folk music” provides. And the key validations for folk music were geographical and cultural isolation prompting musical distinctness.

The problem here is that there are no impregnable walls surrounding genres or eras of music or countries or cities. Creative culture’s sylvian flow ensures that and yet these implied barriers continued to frame much of the debate by drawing definitive lines where there are none and by reinforcing the false belief that culture can exist and develop in isolation in the second half of the 20th century.

Pop cultural New Zealand was never isolated. The culture of America, Britain and Australia had ready access to us and we to it. Every pop cultural movement washed over New Zealand in some way. New Zealand groups shared a sense of mission, information, art, tours and later record labels with their overseas kin. We listened to their music and they listened to ours.

The cultural nationalism at the heart of the argument for the “Dunedin Sound” is both reductive and exclusive. As a consequence entire groups of musicians fall out of the picture, as do inconvenient international strands of influence. Within the history of Flying Nun Records itself there has been a rendering down and simplification and a casting out.

Flying Nun Records and its central vehicle for creating identity and meaning, the “Dunedin Sound” also fit snugly with wider constructions of New Zealand’s national identity. An inclination to number eight wire invention with its do-it-yourself ethos, small business mindset, anti-cosmopolitan and world outlook denying changing racial and cultural makeup and evolving political and social systems can be discerned.

This inward-looking mindset required an indigenous strand of inspiration (in this case a selective interpretation of the New Zealand punk scene) and even produced its own version of the cradle of nationhood and the noble defeat of Gallipoli in Toy Love’s failure in Australia in 1980.

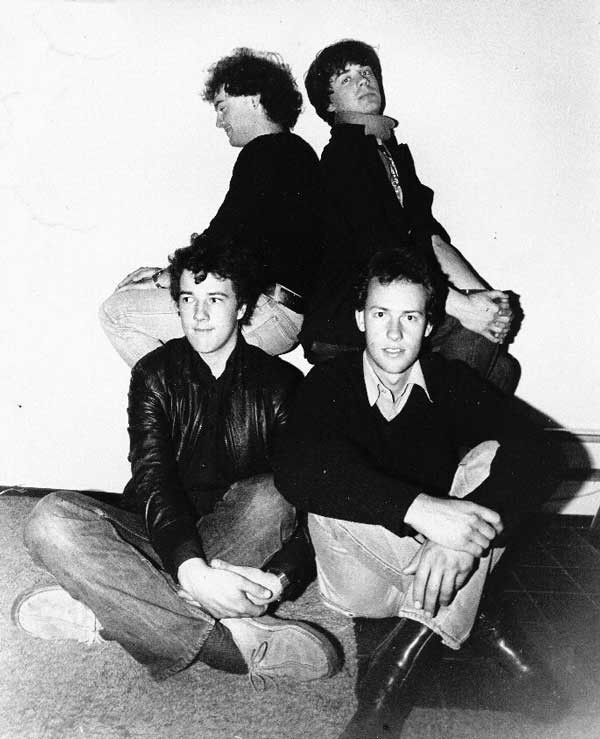

The Chills

That Dunedin produced a cluster of groups and songs whose power and importance is still being remarked upon and whose central figures continue to record, release and perform is undeniable. But they were just one of many post-punk cultural reactions with resultant cultural infrastructure and communities with common roots in punk culture that were prompted worldwide.

Acknowledging this I want to re-examine the history of the punk and post-punk movement in New Zealand and the “Dunedin Sound” groups’ place in it from an inclusive internationalist perspective.

There is a wide although not total acceptance that Flying Nun Records’ roots lay in the arrival of punk rock in 1976 and its slowly emerging New Zealand reaction up to 1980. Punk rock was a national movement in New Zealand centred in Auckland with high levels of interconnectedness through personal mobility, word of mouth and national music media such as Rip It Up and television’s Radio With Pictures. Similarly all the main centres had access to locally released overseas punk records and British music media, including the influential NME.

The Enemy and The Clean moved from Dunedin to Auckland in 1978 and 1979, a migration also made by punk groups from Christchurch and Wellington who were attracted to Auckland’s larger punk community and its all-age venues and pubs.

The first new independent record labels emerged as a result of punk and its consequent post-punk movement in late 1979 and 1980 in Auckland, where Ripper Records and Propeller Records began releasing original music from the burgeoning Auckland scene.

Strong regional scenes developed in Christchurch and Wellington. The swelling number of groups and fans prompted national tours that further connected the nation’s post-punk community. This new era of musical adventure was creatively fuelled by the diverse selection of albums and singles available on import or released locally by increasingly adventurous major labels. Many of the key British and American post-punk groups were chart acts in New Zealand.

Many of New Zealand’s pioneer punks and those they inspired were in creative flux in the post-punk era. They moved with the fast unfolding times. The curiosity that had got them there pushed them on. The basic building block of rock n roll absorbed jazz, ska, electronic sound, art, noise, and psychedelia – whatever fitted. Diversification lost them none of their energy or focus.

Punk had ceased to be just (one) sound and image. It was an aesthetic embracing access and creative control that retained the excitement, iconoclastic honesty, tetchy individualism and do-it-yourself bent of punk rock and sought to widen its musical vocabulary.

In 1981 New Zealand post-punk groups, and in particular, the Auckland scene, followed British trends and fractured further into music cults such as mod, ska, British post-punk sounds, reggae, rockabilly and spartan dub pop.

Echoing the provincialism of the British post-punk movement New Zealand’s music scene decentralised. Wellington and Christchurch had their own independent labels in Bunk Records and Flying Nun Records, the latter influenced by the post-punk ideal of complete creative control. Its founder Roger Shepherd arranged record pressings, covers, distribution (via friends and touring bands) and often recording sessions as well.

The label’s hands-on do-it-yourself attitude was influenced by the small British post-punk independent labels Rough Trade Records, Fast Records and Postcard Records, who distributed their own records outside the system set in place by mainstream companies. This indie label model would be echoed throughout the world in the 1980s and 1990s, connecting the communities that used it.

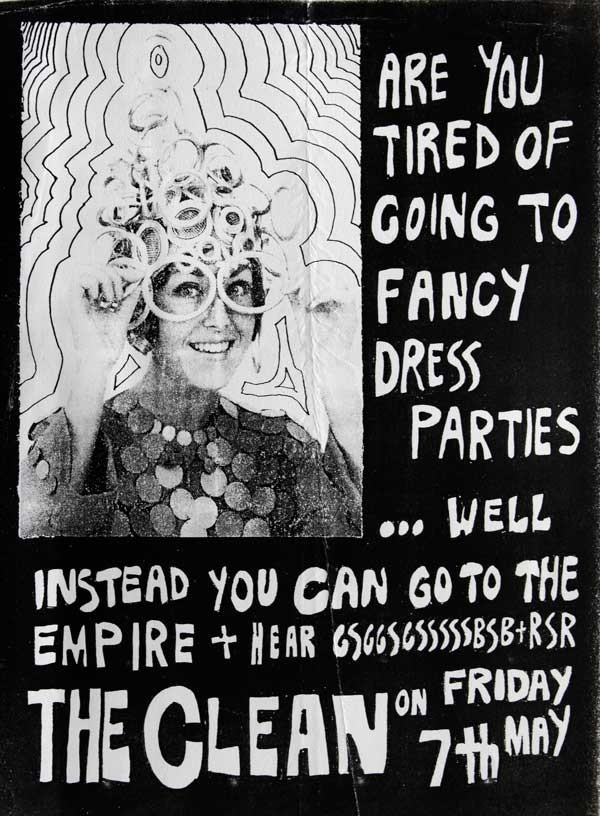

The first Dunedin records released on Flying Nun Records came out in late 1981 – a string of chart hits for The Clean. It was an impressive public response and indicator of the size of a national post-punk movement threaded together by common roots in punk and national tours by groups such as The Swingers, Toy Love, The Features, Blam Blam Blam, The Screaming Meemees, The Clean and The Gordons, who shared a similar sense of mission.

In every city, there were sympathetic record stores stocking the emerging sounds and providing a central meeting point for punks and music fans to exchange information.

In 1981, 24 singles by groups from Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin inspired by the aftermath of punk made the top 50 singles chart. Half as many records again were released independently and didn’t. All the discs contained original songs.

As I’ve already shown diversity of influence was very much a benchmark of the post-punk movement yet it is the Dunedin groups use of older mostly American influences that has been elevated as the template for an original New Zealand sound. The key factor in this elevation is Dunedin’s perceived geographical and cultural isolation, which gave the groups time to develop a distinctive original sound outside of immediate commercial influences.

Too much is made of the newness of music encountered during in this era. It is when musicians encounter influential music that is relevant not the music’s age. The pivotal Velvet Underground and Nico album so often cited as an influence on the “Dunedin Sound” was reissued in New Zealand in 1981 making it available widely for the first time in years.

There was a revival in 1960s garage music in the early to mid-1980s through the Pebbles, Highs In The Mid Sixties, Ugly Things and How Was The Air Up There? compilations and the reissue of groups, including Thirteen Floor Elevators, The Electric Prunes, Love, The Standells, The Chocolate Watch Band; all of which were being imported into New Zealand.

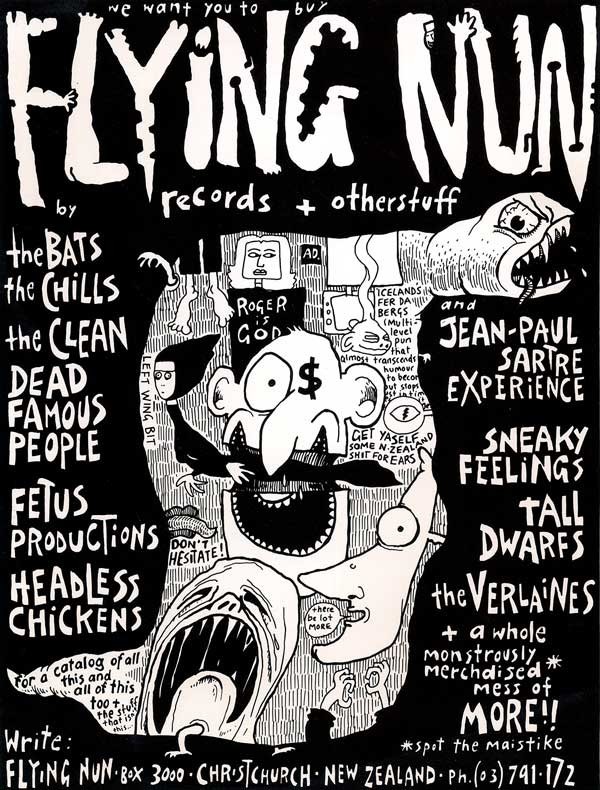

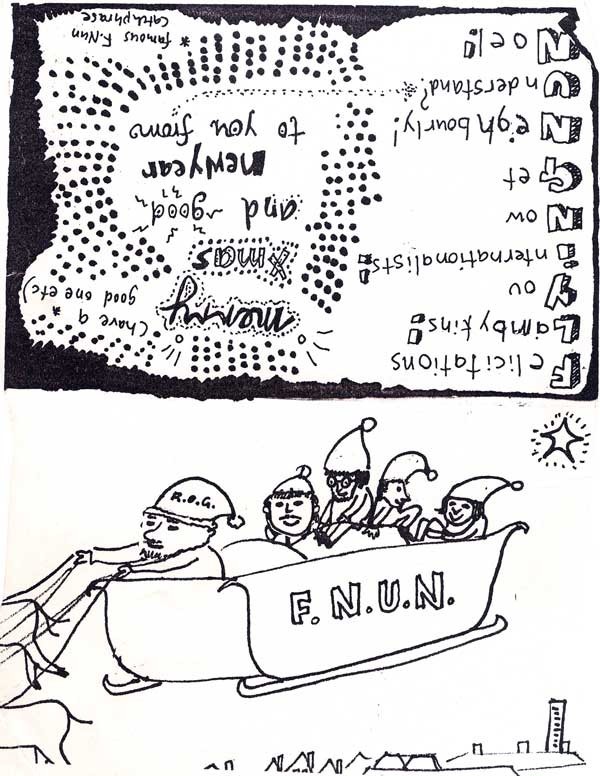

A Chris Knox drawn Flying Nun Xmas card, 1982

This was not a case of geographical and cultural isolation giving a limited choice. It is a case of deliberate choice made from immediately available influences. The circumstances of the “Dunedin Sound” groups selection of inspiration is no different from The Newmatics and their use of ska or soul or Danse Macabre channelling Joy Division and the northern English groups or Nocturnal Projections using Wire.

The assertion of a unique Dunedin Sound can be seen as an attempt to reassert lost provincial autonomy and identity in the face of North Island, and in particular, Auckland domination, as represented by its population base and the major labels and recording facilities based there and the more readily identified multicultural and cosmopolitan musical influences of its groups.

Ian Dalziel and possibly Roger Shepherd in the Flying Nun office, The Dominion Building, The Square, Christchurch c.1985

This also explains why the myth has endured and why it has so many non-New Zealand propagators. Urbanisation is an ongoing worldwide occurrence that allows local and personal investment in its consequences, especially from music communities with similar post-punk cultural roots and a regional base as many indie labels had.

While neither the circumstances nor the cultural context were unique it is still possible through cross-pollination of influence and joint live performances that an identifiable “Dunedin Sound” exists.

Dr Graeme Downes, a music lecturer at University of Otago and guitarist and songwriter with “Dunedin Sound” group The Verlaines hears in The Clean’s songs, “clearly discernable compositional differences that distance them from the mainstream. The use of tonal tensions and certainties.”

Sneaky Feelings

Matthew Bannister in Positively George Street: A Personal History of Sneaky Feelings and The Dunedin Sound, paraphrasing Dunedin musician John Dodd, acknowledges, “a tendency (in Dunedin songs) to sustain or repeat a note or notes while changing the chords underneath. The effect is not unlike bagpipes. While the melody is played on the chanter, the drones sustain a note beneath the melody giving continuity and fullness to the sound.

“This is a common device in ethnic music – the sympathetic strings of a sitar resonating, for example, or the didgeridoo. When folk music is electrified, this drone becomes electrified. This drone becomes a jangle.”

And the jangle of electric guitars is one of the most commonly remarked upon signifiers of the “Dunedin Sound”. Another is sound reverberation. Bannister, who was born in Scotland), and his evocation of Scottish folk music and opinion that the ethos of the Dunedin groups as “punk puritan like the Scottish apostle of Calvinism, John Knox,” links the city’s sound to Dunedin’s Scottish roots. An internationalist interpretation and connection.

Could it be that in the rush to construct a distinct and exclusive New Zealand identity for the country’s British-descended population that the obvious has been overlooked? That the Dunedin Sound is a modern musical echo of the city’s Celtic/ Scots roots?

Could it be that we are hearing modern representations of the skirl and drone of the bagpipes and the poppy jaunt of the fiddle? It is surprising no major ethnological or musicological study of the “Dunedin Sound” has been undertaken given the city’s and University of Otago’s increasing identification with and use of it.

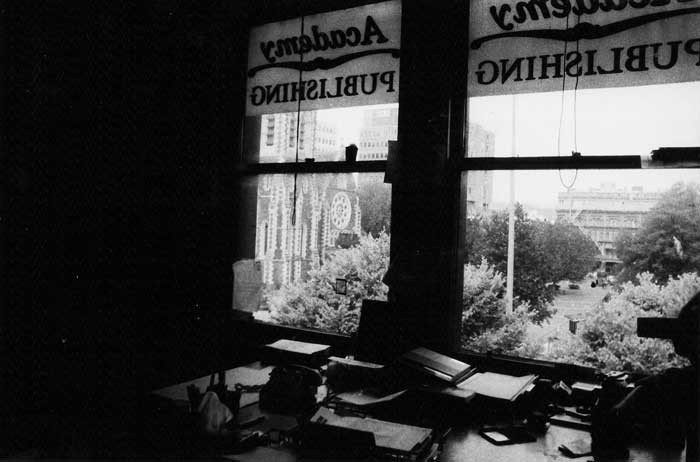

Looking out of the Flying Nun office, The Dominion Building, The Square, Christchurch c.1985

One final question remains. What is the impact of the cultural emphasis on the “Dunedin Sound” on other Dunedin groups? There was more than one musical label releasing Dunedin music. Rational Records released a run of records in the 1980s, including the ironic ‘Funky Dunedin’ by Let’s Get Naked. Xpressway Records was another reaction to punk and post-punk ideals, which gained widespread prominence and acclaim in the city and overseas in the 1990s. Yellow Eye Records and IMD were similarly active. Dunedin had a busy 1960s and 1970s music scene. And yet this music continues to live in the shadow of a handful of groups from the early 1980s.

Regardless of its unproven nature, the “Dunedin Sound” will continue to be associated with the city. Its authenticity will be asserted, sites of memory will be constructed and events organised, and local cultural, identity-related and commercial needs met. It will retain its popular appeal and rarely be questioned. That is the nature of heritage.

--

This story first appeared on Andrew Schmidt’s site Mysterex in 2010. It is used with permission. © 2010 Andrew Schmidt