To keep the coffers full, a career musician has to be supremely adaptable to changing circumstances, musical genres, gigs, venues and bar owners of all stripes. Mike “Spike” Walker, gifted and versatile pianist, bandleader and long-time pivot of the Auckland music scene, typifies the lifestyle.

Mike Walker

Once music gets you it doesn’t let go and Mike has been in its thrall from the very beginning. For half a dozen decades – since his first residency aged 19 at the bohemian Montmartre jazz club in Auckland – he has been plying his keyboard skills onshore and off. He has performed in venues ranging from hole-in-the-wall jazz clubs to musicals, cabaret, tours and recording studios, cruise ships, jazz festivals, and on radio and television. While he hasn’t made any albums of his own, he’s been a session man on more than 30 albums by others, and counting: “there’s not one of my own other than three or four radio broadcasts”.

After almost 10 years in England, Mike Walker returned in 1982 and since then has continued to work extensively around the country with his trio, in band work, accompaniment and show work, session gig and functions, residencies, RNZ and TVNZ appearances, on various tours and at national jazz and blues festivals.

The 80s and 90s tell just a little part of the story: he and the band toured New Zealand with Billy T James; he worked nationally with Ray Woolf and Billy Kristian (and still does); was resident at the Regent Hotel, the White Heron restaurant, and the Travel Lodge; accompanied Shirley Bassey, US jazz singer Joanne Jackson and New Zealand jazz trumpeter Edwina Thorne; recorded with Hammond Gamble, Billy T, Jacqui Fitzgerald and others; performed regularly with the Peter O’Gara Big Band, and worked on TVNZ with such shows as Search For a Star, the Billy T James and Ricky May specials, and the Miss New Zealand and Miss Universe shows, among others.

The Mike Walker Trio, 2011: Mike Walker, Pete McGregor and Bruce King

Down times these days are spent with musician friends – maybe Ray Woolf and Billy Kristian or jazzmen Bruce King, Frank Gibson Jr and Pete McGregor – or with Wendy, Mike’s wife of 50 years, and their two daughters and two grandchildren. That is, when he is not working after hours at the Point Chevalier Memorial RSA. For the eighth consecutive time, Mike is the elected president of the Auckland Jazz & Blues Club, booking talent for the 48 Tuesdays a year it operates under the RSA roof, and never too far from the keyboard, his natural home.

Learning piano

“When your whole family are musicians, right from the word go you are learning. Then from about nine or younger I went to the nuns. We weren’t Catholics, but Mum and Dad were quite well known in Thames and the Catholic school was a hundred yards up the road. I had lessons till I was about 14 from some very good teachers. Never had any of this being rapped on the knuckles rubbish.

“I’ve always taken a keen interest in other instruments, too: drums, bass I play a bit of or used to, and I played flugelhorn in the Thames Citizen Brass Band. About the only thing I don’t play is guitar.”

Herb’s band

“My father, Herb, had a dance band. It consisted of saxophone or trumpet, both of which he played, then trombone, bass, drums and piano, sometimes guitar. My uncle was the bass player in the band and my mother, Eileen, who had more letters than me as far as classical goes, was the piano player. It was very good and very popular. They had a regular Saturday at the Majestic Ballroom, next to the famous Brian Boru Hotel. That went for a long, long, long time. They even had buses bringing people in from the Hauraki Plains – all sorts of places.”

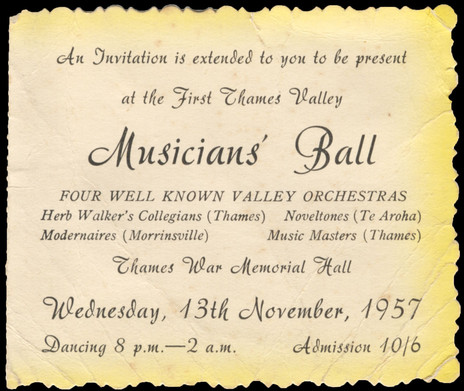

Mike Walker grew up in a musical family in Thames. This invitation to the 1957 Musicians' Ball in Thames features his father Herb Walker's Collegians and three other local bands. At the time, Mike was 17 and just out of the army. - Chris Bourke collection

Going pro

“At high school we had a school band made up of three or four mates. I can’t remember a proper concert, my first one, because I just always kept on playing, although I never played in Dad’s band, strangely enough. I played in another band that was opposition to Dad, which he thought was a great joke, but by this time he was about to give it away. He’d had enough. I think I was 14.

“Then in 59 I got a call from a school friend, Ned Sutherland, a very good guitar player, who was in Auckland at university or teachers training college. He’d been offered a touring job backing singers Vince Callaher and Kahu Pineaha, who were managed by Phil Warren. Would I be interested? I was 19.

“At this stage I was working for Dad in the bakery. Being the boss’s son, I was more or less on call. In those days you weren’t allowed to bake on Saturdays or Sundays, but if you were the boss’s son you just baked with him on those days. We used to supply all of Thames, down the coast – Whitianga, Coromandel, on the Hauraki Plains – Paeroa, Tirau and as far as what would have been the motorway in those days.

“I remember turning to Dad at 8 o’clock one morning and saying, ‘Neddy’s offered me this touring job, what do you think?’ He said, ‘Bloody well take it, son, take it. I’m sorry I never went professional.’ I think he thought it’d be a three-month thing and I’d be back. That was my first professional gig.”

Early days at Montmartre

“I came to Auckland with Neddy after we’d done that New Zealand tour and we were on top of the world, so we went to Sydney. It was Ned on guitar, Rick Laird, bass (he ended up playing with Mahavishnu Orchestra), drummer Barry Woods, Brian Smith on sax, and me.

“Ned got good work, because he was also a singer and a good guitarist, which was what they wanted in those days, so I came home for a holiday in Christmas of 1960 and went down to Thames. One night I got a phone call from a guy called Neville Whitehead, who I didn’t know at the time. The Montmartre was looking for a piano player, because Ronnie Smith was leaving, and somebody had said that I was back. I went up, played one night and they said the job’s yours.

“Montmartre and Picasso were both operating at the same time, and this was part of the reason Montmartre thought it was time to get another piano player. Ronnie would say to Neville, ‘Take a solo’, then he’d run across to the Picasso, have a drink, listen to the band over there, then run back. True story.

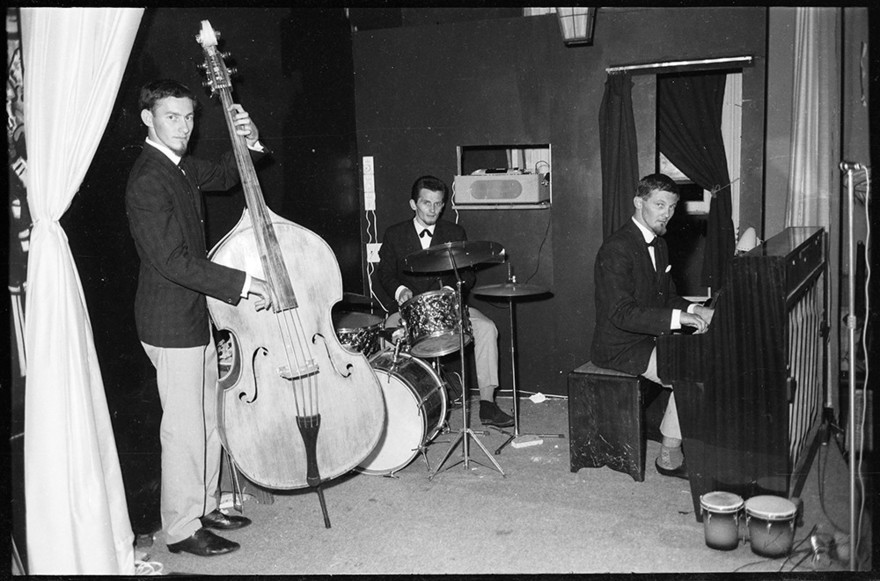

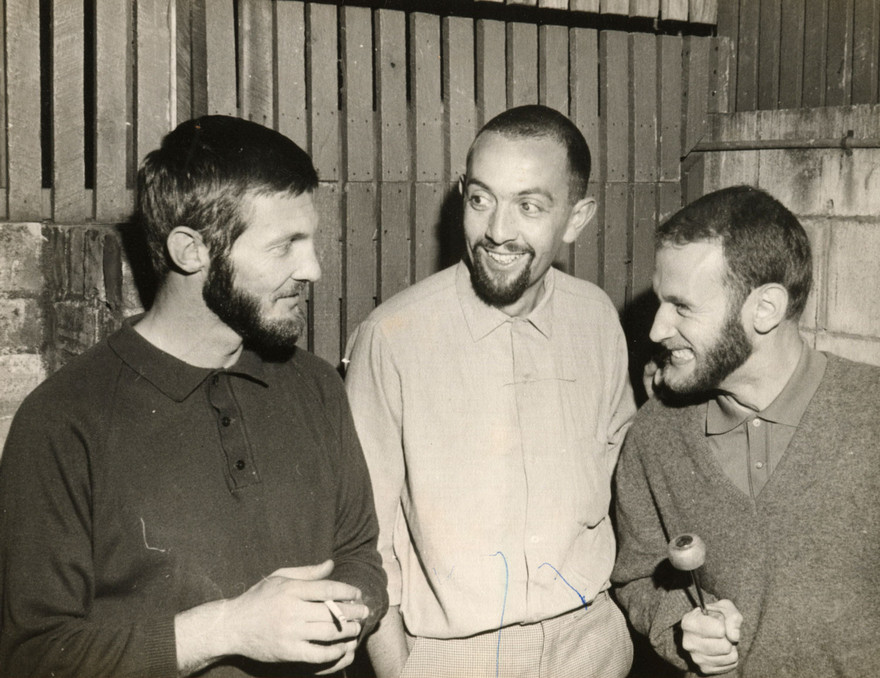

Mike Walker Trio: Neville Whitehead playing double bass, Frank Conway on drums and Mike Walker playing piano, at the Lautrec Coffee Lounge on opening night. - Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 1269-E161-28

“I started with Neville on bass and Frank Conway on drums, then Tony Hopkins replaced Frank, and Kevin Haines replaced Neville when he went away. I was lucky to always have a very good bass player and drummer with me. Electrics weren’t heard of back then, but later I got this Vox electric organ, one of the first Vox. I thought it was marvellous. It was actually terrible.

“Montmartre was a big deal – five, six nights a week, upstairs – and it paid the grand sum of £25. I was there for about five years. We had all sorts of good nights, because it was one of only two or three so-called nightclubs in Auckland. No booze, of course. It’s still there, but it’s now a Korean restaurant.”

Montmartre’s kingpins

“The Montmartre was upstairs, and downstairs was the Lautrec, a real coffee bar. Rainton Hastie and Brian Taylor owned them. Rainton was always looking for other things to do. He was responsible for the strip clubs. He said, ‘Ahh, you guys, why don’t you grow a moustache or a beard?’ the Montmartre being French. We didn’t knock him and I’ve had mine since 1961.

“They were chalk and cheese. Rainton was flamboyant, a hard case, and into this, that and the other thing, and Brian was very straight. He ran it very well and they both made a lot of money from it. They put a lot of emphasis on weekends on what they loosely called floorshows. It was often just one person and not necessarily a singer. We had all sorts – ventriloquists, magicians, stand-up comics – but the singers were all the big names.

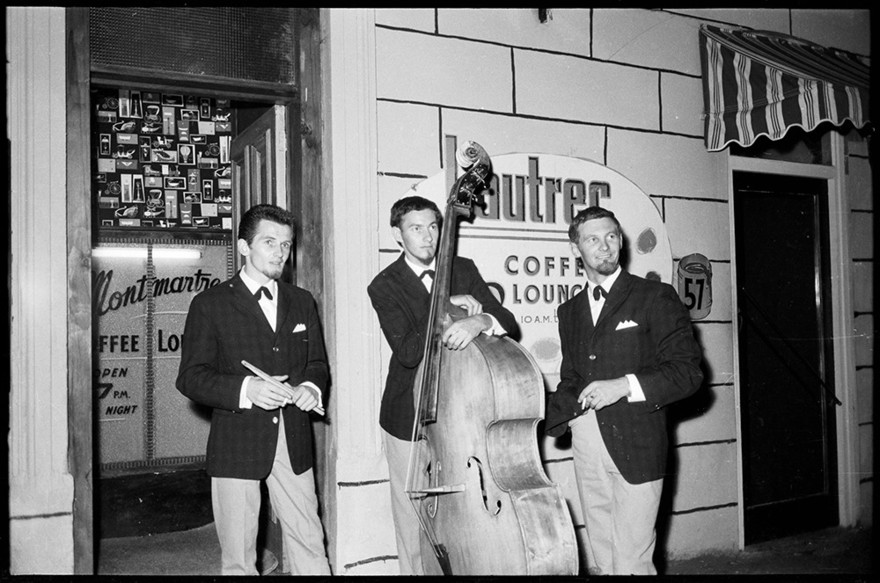

The Mike Walker Trio standing outside Montmartre coffee lounge and Lautrec coffee lounge on the opening night for Lautrec, which was across from where the Auckland central library now stands on Lorne Street. From left: Frank Conway, Neville Whitehead, Mike Walker. - Auckland Libraries, Rykenberg Collection, 1269-E161-29

“When I first started there, there were rehearsals on Thursdays with the weekend’s singers. The singer would arrive with a couple of records, give them to me and say, ‘The tunes I’m gonna sing are on here.’ ‘No, I thought, no!’ So I started putting the law down, saying this was not right. ‘You are making more money than us, get yourselves organised and get charts written out. They don’t have to be big orchestrations, just chord sheet – start, finish, blah blah blah.’

“My name was sh*t, but they all turned around and did it, and now when singers do a gig they’ve got a bagful of charts. I think, ‘Great. I’ll take responsibility for doing that.’ The big stars didn’t think that they should have to do it as it was cutting into their money. And here was I, cheeky bloody piano player.”

Thelonious Monk

“One night at the Montmartre in a break I was going outdoors to have a breath of fresh air, and standing down the bottom in the queue was the great Thelonious Monk. The first time I’ve ever been tongue-tied. I stuttered and stammered and said, ‘Mngmnmgn … come up, come up’. So he and the bass player came up. The bass player played a couple of tunes with us and then I went back to where Thelonious Monk was staying in a Parnell hotel, and spent an hour or two with him. He was a wonderful, wonderful man.

“It was funny, because up till then, I could never settle with Thelonious Monk music. It was always a bit something else. I could never quite gel with him. But having spent an hour with him, it fell into place completely. It was amazing. He was the first genuine nonconformist that I’d ever met and I think it clicked in my brain that that’s what his music is – it’s totally natural, nonconforming. He’s not putting anything on, he’s just playing. That’s him. That’s the way he talks. Lovely man, lovely wife. Boy, I went away with my hair standing up on end for a few weeks after that.”

Jazz for “free”

“We were asked to do the second Tauranga Jazz Festival in 1964 with Marlene Tong, but it was all freebie then, so I told them no. We were playing at the Montmartre till two o’clock in the morning and it wasn’t fair to ask the guys to drive down to Tauranga for nothing, unless they gave us petrol money at least. They said okay, so we drove down. I remember the figure – £10.

“In those days the festival was in the town hall and a big deal. We had a big crowd, jam-packed, and when I asked for the money, ‘Oh no,’ they said. ‘Whaddya mean, no?’ we said. ‘Everyone does it for nothing,’ they said. The guy that had agreed to the petrol money got in the sh*t over it. As well as that, the cheeky buggers recorded two or three different bands, made a record and sold it.

“Marlene Tong was wonderful, a part-Māori, part-Chinese lady singing like Ella Fitzgerald or Sarah Vaughan, her favourite. She had a great sense of humour and would just get on with it. She knew what she wanted. Jacqui Fitzgerald was equally good. We recorded the album of the year with her in 1985, The Masquerade is Over.

“Suzanne Lynch is the same. She is absolutely, totally confident. She’s organised, knows what she wants and, boy, when you’ve got a singer like that it’s great. You can sit back; you don’t have to worry about whether they’re going to miss a beat or anything else.

“She can do the whole feel – the jazzy thing, pop, rock. We did a gig in Whakatane a few years ago where she was supposed to be the guest and do three or four tunes in each set. But the singing guitarist had got sick and didn’t make it. She sang rock all night – all night. ‘I said, Sue, you don’t need to do it, we’ll play something.’ ‘Nah, no, I’ll do it, Spike.’ ‘Okay, away you go.’ She’s lovely.”

Embers and El Matador

“After Montmartre I went down to the other end of town to the Embers and played there for a couple of years with my trio, Les Still and Roger Sellers, and then to El Matador.

Mike Walker, Les Still and Roger Sellers at Auckland's Embers nightclub in the early 1960s - Dave Ross collection

“Matador had music seven nights a weeks and they were pretty free about what you could play of jazz-type tunes, but you couldn’t play rock ’n’ roll. It was always a trio with a singer there, with Les and either Frank Conway or Bruno Lawrence on drums. Tommy Adderley was the singer the whole time I was there. Tommy called the band the Adderley-Walker Movement.”

The Colony

“The Colony was a late-night place owned by Bob Sell. On Fridays and Saturdays, we’d all finish at El Matador at midnight and go up to the Colony on Wellesley Street and play till three in the morning. I suppose it was a convention club.

“We played till 2am at the Montmartre and the same with the Embers. They were all late-night places. Quite often we’d go a bit later than that, except my wonderful bass player, Les, used to say, ‘No, I’m here ready to start on time and I’m going to finish on time.’ Come two o’clock he’d say, ‘See you, guys,’ put his bass down and go. He never got pulled up over it, because he was within his rights and he was a wonderful bass player.”

Playing bass

“I did some [bass] gigs early on. I was sick of piano, because I had a reputation for being a bit of an outlaw on it, so I got pissed off and said, ‘Right, you don’t like my piano playing, I’ll play bass. I was always a fan of it. For a piano player, a bass player’s your biggest mate in the band. So I played bass, but not for long. I did buy an electric, but in the beginning it was my uncle’s upright.

Mike Walker on bass, Canberra 1960.

“Someone said there’s a photograph of me playing bass at Tauranga Jazz Festival 1964 with Bruce King on drums and Dave MacRae playing piano. Goodness me, my old friend Dave. He can’t remember it – probably doesn’t want to remember it. What the hell was I doing, playing acoustic bass back then?!”

Early entertainment laws

“Tommy Adderley and Barbara Doyle don’t get the accolades that they ought to have, because those two, more so than anybody, in my opinion, were responsible for relaxing the laws on entertainment. You would not believe the stupid laws.

“At the Montmartre at one time you couldn’t have any more than two people on stage. That was the Council law. We were playing upstairs and the doorman downstairs had a buzzer by his heel. If he saw the law coming or the Council pulling up in their car, he’d flick this buzzer, which’d go ‘bzzzz’ on stage and one of us would disappear.”

The Ranch House

“I did a lot of work at Barbara’s Ranch House. My trio, which was Les Still and a Scottish drummer called Johnny McGuire, was resident. We used to do our usual bit as well as backing. Barbara brought in quite a few overseas acts and for those she would get me to employ sax and trumpet, and the band would go from a trio to a four, five, six-piece band. It was a restaurant, but you couldn’t do this and you couldn’t do that as far as alcohol [was concerned], but she went ahead and just did it and broke all the rules.”

Tommy Adderley’s bars

“Tommy did the same with his clubs, Granny’s and Granpa’s. These clubs are famous for various reasons, one was that he threw caution to the wind, got done a couple of times for selling alcohol and the booze was confiscated. I presume [the law] was a money-making thing. It was the early 60s and into the 70s, and places like Montmartre were jam-packed every night. There wasn’t a drinks licence, so they created this new one for when there were more than two people on stage. As I say, it didn’t last too long because we just said stuff you.

Advertisement for Tommy Adderley's Granny's club in Durham Lane, with the lineup including Adderley's Headband, Mike Walker Group and Bob Paris.

“Tommy had a great sense of humour and was easy-going. A very gentle man. I remember one time in a place upstairs in Wynyard Street where we were doing a function. There was an idiot there, as there always is, who wanted to fight Tommy. Tommy was the last person to ever get in a physical fight with anybody. I don’t know what the guy was on about, but he was getting really aggressive. We were packing up and I just happened to accidentally hit him with my amplifier as I went out, and he tripped and went arse over kite down the stairs. So that put an end to him wanting to fight Tommy.

“He and I worked together a long time at the El Matador and the Colony, around ’66 on, and I was more than pleased to lean on the poppy side of music then, as he was, obviously. We were very close, but there were times when he would say, ‘No, wait a minute, man. I don’t want to do that song.’ He was good like that.”

Auckland venues

“The Hi Diddle Griddle started it all off, really, a tiny place in Karangahape Road. It was one of the first so-called restaurants that had jazz. It had some wonderful people – Judy Bailey, Lou Campbell – the generation before mine.

“I did Checkers with my Quintet, the Toby Jug Restaurant once or twice, and Sorrento, which was similar, for functions. Then there was the Troika restaurant; Bali Hai, which was more of a club or bar, Paris Boulevard (that was above Eady’s, I think) and La Boheme, quite a big restaurant owned by Bob Sell. I did the Oriental Ballroom, Delmonico, Trillo’s, a few functions at the Milford Marina Hotel way, way back, and I played bass with Merv Thomas’s band at the Peter Pan Cabaret for a short time.

“I started at Mojo’s for Mr Phil Warren, too. He somehow managed to import a Hammond organ. Woohoo – I loved it! In those days you couldn’t get a Hammond unless you were a church. He put a manager in and we didn’t get on at all, right from the word go, so I wasn’t there for too long, which was an awful shame.

“I did the Top 20 in Durham Lane, maybe with Larry [Morris] or Tommy [Adderley], and there was Tommy’s club on the corner of Durham Lane and another little hundred-yard street. It used to be a stable or a barn or something. It might’ve even been a jail. Downstairs was Granny’s and upstairs was Granpa’s.

“And with Prima Swing Riot, the Louis Prima tribute band, we did regular Sundays at the Civic Wintergarden for dances. It’s a lovely big room a couple of flights underneath the Civic that they use for functions.

“The band did Western Springs a couple of times, one of them as the support band for Chuck Berry. We called ourselves Walker, Thompson, Kristian, Hill after our surnames: Billy Kristian [Karaitiana], Jimmy Hill, myself and Chris Thompson, a singer/ guitar player who ended up with Manfred Mann and wrote several hits, including ‘You’re the Voice’. A big star.

“We also did the Auckland Town Hall once or twice with Billy T James as well as another big show there that Howard Morrison produced. But most of the time I had residencies, which occupied five or six nights a week, so I was lucky.”

Broadcast shows

“In the 60s I did Radio New Zealand big bands with Bernie Allen and half-a-dozen other bandleaders. I was also very lucky to be the in-favour piano player of the time when I came back from England in 1982.

“Bernie and Tony Baker were in charge of all the music on TVNZ back then, and with Tuhi Timoti [guitarist] and musical director Jimmie Sloggett we did practically all the television. The band was piano, bass, drums, at least one guitar and then sax, trumpet and trombone.

“There were talent quests, TV specials, such as the Billy T special, and [earlier] music shows like C’mon and Happen Inn with host Peter Sinclair. They were full on. Rehearsal all day on the Thursday and all day Sunday, filming it and running through it over and over and over. And then it dried up.”

That nickname

“It comes from Jimmie Sloggett, the bandleader for C’mon and Happen Inn. A wonderful musician and great saxophone player with a big fat tenor sound. Jimmy had this little language thing going of nicknames for everyone and mine was Spike Faulkner. I don’t know where he got it from. It was also a bit of a pointed accusation to the cartoon in the Herald or the Auckland Star – Spike and Tyke, the father and son bulldogs.”

Billy T James

“There was nothing but good about Billy T. A wonderful man to work with. He was just one of the boys. In the early days when we were touring in the Hi-Ace van, we used to put him in the middle in the back seat. That’s the worst seat when you’re travelling anywhere, because you’ve got no armrests, so you’re rolling all over the place. He used to say, ‘You bastards! You bloody well put me in this seat again. I’m close to being the boss. I’m the star and you guys are …’ We’d all laugh at him, ‘Shut up, Billy’.

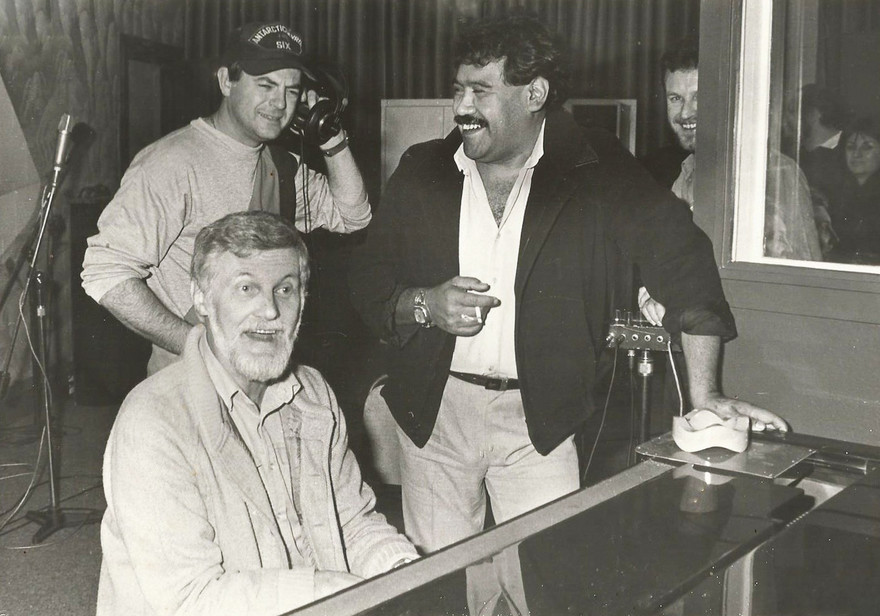

Mike Walker with Billy T James and Frank Conway at far right.

“One time we were in Waiōuru, the army camp, and the next night we were to be in Whanganui. When we finished Waiōuru one of us said, ‘It’s early, only 10 o’clock, why don’t we drive through to Whanganui?’ We all agreed and got in the van, but found there wasn’t enough petrol. I was driving and we pulled up outside the little shop in Waiōuru where the petrol pumps were, but there was nobody there. I got out and banged on the door, and two heads popped up from behind the counter: a him and a her in their army uniforms, looking sheepish.

“He stood up and saluted me then gets out and says, ‘What can I do for you?’ ‘We’d like to fill up, please.’ He said, ‘Yes, sir. Just sign here, please?’ I had to sign, so I wrote Major Walker – and filled the van up. The other guys thought it was hilarious and Billy did, too, but we were terrified that they would realise, ring the agent and she’d call us the next day and give us hell, but nothing ever happened. So it was always ‘Major Walker, Major Walker, come here, do this …’

“Billy was generous, too generous, as far as hangers-on went. One or two of his close associates steered him totally wrong money-wise into a business downtown that they were going to turn into a music centre. Everything was invested in the whole lot and it was a flop. He lost thousands on that one.

“He was just lovely. After his heart operation he did another tour, this time with a trio: Billy, me, Patrick Kuhtze the drummer, and vocalist Taisha. We held our breath every night, because he was chopping and changing his normal routine and I’d be left looking silly when he was waiting for me to give him an intro to a tune. That short tour wasn’t too good. It wasn’t long after that that he died.”

Tours and cruises

“Later I was musical director for Howard Morrison in Honolulu – that didn’t last too long – and then in New Caledonia with Ray Columbus, and again with my band in New Caledonia. I also did cruise ships.

Mike Walker on tenor saxophone, New Caledonia, 1960.

“One was from New York to Bermuda over a week. It took two days to chug along to Bermuda where it stayed for a day and then motored on down to the other end where [in 2017] they had the America’s Cup race. It stayed there for two days and then back to New York. Bermuda was great. The bandleader offered me a job, but my wife – my girlfriend at the time – wouldn’t have been able to come, because they were very strict with visa, etc. But what beautiful place.

“We were in and out of Customs between New York and Bermuda, because Bermuda’s a British protectorate, so on board the ship I was given a licence to play that was more or less a Green Card, which enabled me to work in the States.”

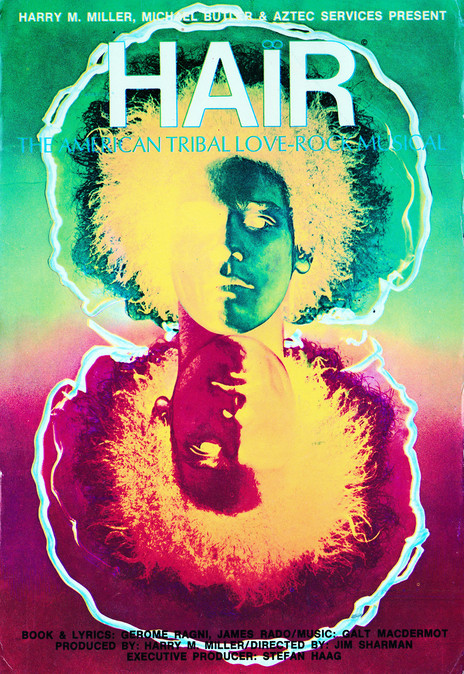

Hair: the tribal love-rock musical

“It was 1972 and I think I’d finished at the Embers. Somehow the show’s musical director, Patrick Flynn, got hold of me and asked me to do it. I said yes. We toured New Zealand. Tuhi [Timoti] was the guitarist and later Terry Villis; Peter Knapp was the bass player, the drummer was Ron Sandilands from Melbourne and Bruce Morley played percussion. There were also a couple of brass players.

“I was the piano and organ player in the beginning, but then Patrick went back to Australia to do Jesus Christ Superstar, so I was made vocal director which, really, was just a nice way of saying I was the rehearsal piano player for the singers. I didn’t get any more money or acknowledgement.”

Hair promotional postcard.

“I knew Harry Miller [the show’s producer] and he knew me, because we were both sort of at the start of that entertainment thing in Auckland. There is something that I can’t recall about he and I. I know it wasn’t anything bad. It might’ve been a lady … But that’s why I was amazed when I got asked to do the Hair thing, because I thought Harry’s the boss man and probably not that keen on me, because even then I had the name of the ‘jaaazzz’ piano player. [Being pigeonholed] cuts your work down – not completely, but in those days it did.”

England

“After Hair, I formed a band with Tuhi, Billy Kristian, Jimmy Hill and Chris Thompson to play at the Tainui Tavern and when we split I went to England. I was there nearly 10 years. I worked all over and in London clubs: the Playboy Club, Dorchester Hotel, Half Moon, Stringfellows, Bulls Head, Bridgehouse.

“I was with a couple of different bands and thoroughly enjoyed it, because I was freelance. I was first and sometimes the last person they’d call if they needed a replacement piano player in some very good bands. The Morrissey Mullen Band, a top British jazz-funk band of the 70s and 80s, was a good one. Bruce Lynch and Frank Gibson Jr were also in the band. I also toured with Leo Sayer and at Ronnie Scott’s I did a couple of spots with Mark Murphy, a marvellous American singer, doing support to Stéphane Grappelli.”

Alley Oop: Mike Walker (keyboards), Trevor Harrison (vocals), Billy Kristian (bass) and Jimmy Hill (drums).

“Leo Sayer was a lovely guy and he had a lovely wife, but she, unfortunately, had cancer and it wasn’t very nice to be travelling with. I lost that job, because Adam Faith, who was his manager at the time, thought the keyboard player was too jazzy and too old. I would’ve been about 34. That’s what they were like then.”

Tap-dancing

“For two or three years in England I played for a brilliant American tap-dancer called Will Gaines, touring all over the place. He’d been in the army there during the war and stayed on. It was Roger Sellers on drums, Billy Kristian on bass, a guitar player called Ed Speight, Gaines and me. We’d put four pickups on the corners of the stage and plug them into the PA, so we could play at whatever level we wanted and Will could tap at whatever level he wanted.

“He was a hard case, talked at a hundred mile an hour. He had a big American car with a folding, portable stage about three metres wide strapped on top. He took it wherever we went in case the floor wasn’t good enough. He wore heavy hobnail boots with no laces all day long and would swap them for his dancing pumps. He told us, ‘My feet are working all day holding these boots on, so they’ve become extremely strong.’ And they sure had, because, boy, could he dance.

“Then we had a season with another two US tap-dancers, Honi Coles and Chuck Green. The three of them were totally different. Will was like Dizzy Gillespie – he just played. He’d say, ‘Play whatever you want. Just go on, do it.’ Honi Coles had charts and was like a black Fred Astaire – a wonderful dancer and real organised. He used to do master classes. The other guy was in between them, a hard case. They were my favourite people to work with.

“I’ve always loved tap-dancing and would’ve loved to have done it. For organ players it’s great for using the pedals – up and down, up and down. I came back to Auckland at the end of ’82 and I’ve been here ever since.”

Auckland Jazz & Blues Club

“The club’s been very good financially and we’ve got a great committee: secretary, treasurer, sound man and three other people who have their own jobs. I just leave them to it. The place is very well run.

Mike Walker Trio backing Ray Woolf (L-R): Mike Walker, Pete McGregor, Ray Woolf and Bruce King.

“We set up on Tuesday afternoon, transforming the big barn space of the Point Chev RSA with tables, soft lighting, candles and so on. We’ve got sound system all over the place and enough microphones for everything up to a 20-piece band. The bands start at 7.30pm, have two breaks and finish at 10 o’clock.

“The RSA have been really accommodating and they should be – we make them good money. And if somebody big came through and wanted to play I would say okay, we’re gonna stay on. It would be down to the bar staff to say yay or nay, and I’ve never done it yet, but it wouldn’t be a problem. Because it’s a Tuesday and dear old Auckland, there’s nowhere else to go. The streets are empty.”