Their eponymous LP was an eclectic affair partly due to the conflicting aspirations of its greenhorn songwriters Smith and saxophonist Denys (aka Dennis) Mason. “Denys wanted to be Bill Withers, so everything he wrote sounded like it could have been a Bill Withers song, and I desperately wanted to be in the Eagles, which made the whole thing ridiculously schizophrenic,” Smith says, laughing.

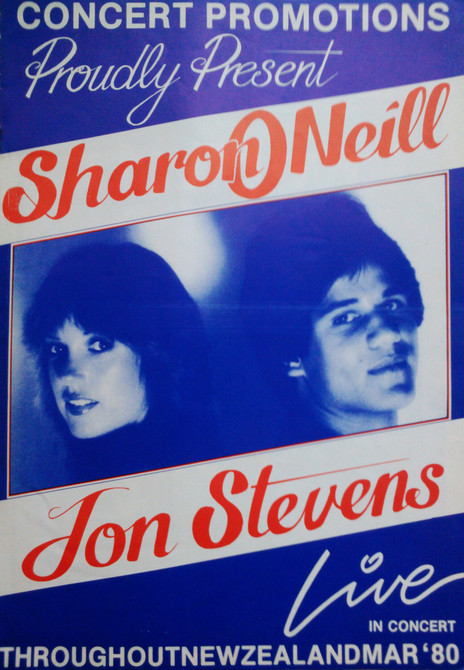

Following a stint playing with Chris Thompson in London, Smith returned with the demo of Jon Stevens’ biggest New Zealand hit ‘Jezebel’ and Stevens recorded Smith’s ‘Running Away’ in the United States with a cast of LA session heavyweights. Smith toured New Zealand and Australia with Sharon O’Neill and his vocals, keyboards and guitar playing was a staple of Wellington jingles and sessions throughout the 1980s.

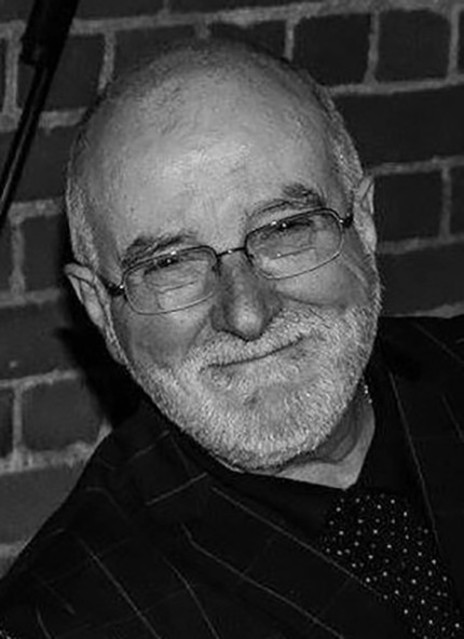

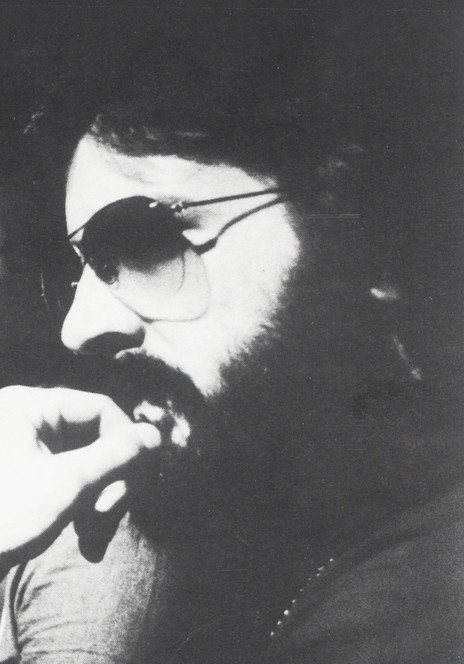

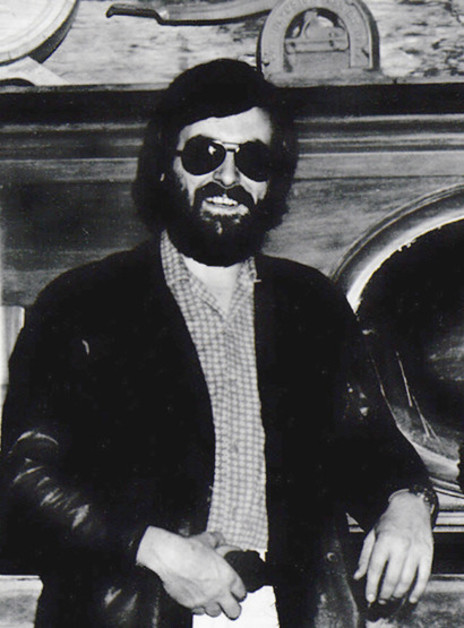

Born in Hastings in 1949, Smith’s mother was a music teacher but he learned piano from the nuns at St Joseph’s School. He completed his piano exams and also took up guitar at the age of 11.

By his teens he had become part of a small group that would strum guitars out the back of Sutcliffe’s Music Store in Heretaunga Street on Friday nights. One day in 1967 while Smith was mowing his lawn, a Citroën Light 15 pulled up and out jumped schoolmate Geoff Harman and his mate Mike Corless.

The boys were in a band called The Afta Set whose lead guitarist worked at a bank and was being transferred out of Hastings. They had seen Smith playing at Sutcliffe’s and took him off to meet bandleader and bass guitarist Ali Zurcher. Although Smith was no lead guitarist he jumped at the chance to play in a band.

When it transpired the guitarist’s transfer was less than 15 miles up the road to Napier, he and Smith were retained, vocalist Harman was fired and rhythm guitarist Derek Parker moved to vocals to make way for Smith, who borrowed Parker’s Fender Mustang.

Eventually he needed a guitar of his own, so he withdrew all of the money from his Post Office savings account and set out to buy the Framus double-cutaway on display high on a Sutcliffe’s shelf. While awaiting a salesman, he noticed some of the staff screwing the legs into what turned out to be a Teischord C organ.

Smith went into Sutcliffe’s music store to buy an electric guitar and walked out with an organ

“I do not know what happened,” Smith recalled, “but I went in with the money to buy an electric guitar and I walked out with an organ. I thought, ‘What have I just done?’ And I went to the first rehearsal, which was in Ali Zurcher’s bedroom, and they said, ‘That’s a weird-looking guitar case.’”

The new instrument immediately broadened the band’s repertoire, but there was a personnel change when Raice McLeod replaced drummer Mike Corless on his return to Hawke’s Bay from Whanganui Collegiate. McLeod’s stay was brief as he was offered a spot in The Quincy Conserve at the Downtown Club in Wellington in March 1968.

Smith had relatives in the capital and would catch up with McLeod and hang out with the Quincys whenever he was visiting. When bass guitarist Dave Orams threatened to quit The Quincy Conserve, McLeod called Smith to ask if he’d be interested in joining.

Smith had been playing bass at the Mayfair in a trio with Sutcliffe’s employee Owen Knight, who would supply Smith’s gear. There were even occasional big band gigs and an experience with Garth Young in which Smith bluffed his way through Young’s charts.

With a Gibson EB-0 bass borrowed from Knight, Smith flew to Wellington to audition for Malcolm Hayman and The Quincy Conserve. McLeod told him he had the job and the band would be in touch, but once Orams got wind of the auditions he snaffled his spot back.

Purely a pop covers outfit, The Afta Set became The Squires, picking up Craig Alexander from The Matloes and John Lindsay from The Contacts. While playing one night at the Top Hat in Napier, Smith asked touring pop singer Larry Morris if he knew of any bands in Auckland looking for a keyboard player.

Morris gave him the number of Dallas Four leader Jimmy Ford and Smith again headed to the airport and off for another audition. This time he was successful and, after quitting his job in advertising, two weeks later had replaced Graham Gill in The Dallas Four.

The strong vocal group had formed in 1964 and released five singles on four different labels. By the end of 1969, they were feeling stale, and when original bass guitarist Basil Peterken indicated he was thinking of departing, Gill was the first to walk. Drummer Ford and original guitarist Dody Potter convinced Peterken to remain, and they were happy for a fresh face in Smith.

The reprieve was short-lived and Peterken left on New Year’s Eve. His replacement was former Action guitarist John Kristian. Although working for a wage on Phil Warren’s Auckland nightclub circuit, The Dallas Four were wooed away by Albanian wheeler-dealer John Muharami and his promise of 50 percent of the door at the new club he was opening called El Bongo.

“El Bongo?! I’m not playing in a place called El Bongo,” declared Potter. When pressed for a better alternative, Potter offered up The Tabla. Thus, The Dallas Four’s new residency became The Tabla and Muharami became known as Johnny Tabla.

The Tabla and its clientele were a heavy experience and despite making more money than they had with Warren, when he came courting with a new residency at a new club and a new deal of 50 percent of the drinks profits, The Dallas Four returned to their former mentor.

But the new club wasn’t ready and Warren put them in charge of The Montmartre for several months while The Crypt was being finished. Once it opened, it became evident the drinks profits could be easily written off against costs and the band were back to making peanuts. Potter left, Kristian moved to guitar and Ian Rowe came in on bass. Auckland stalwart Sonny Day even joined for a while.

Kristian was the next to go, replaced by former Classic Affair guitarist Peter Timperley. But soon after, Timperley and Bob Smith threw in the towel on the same Saturday night and wandered from The Crypt down to Granny’s, straight into Granny’s owners Tommy Adderley and Dave Henderson.

Upon revealing they had just left The Dallas Four, Adderley suggested they put a new unit together with unemployed ex-Troubled Mind drummer Johnny Banks – who Smith had known from Hawke’s Bay – to act as support band to Adderley’s own Headband at Granny’s.

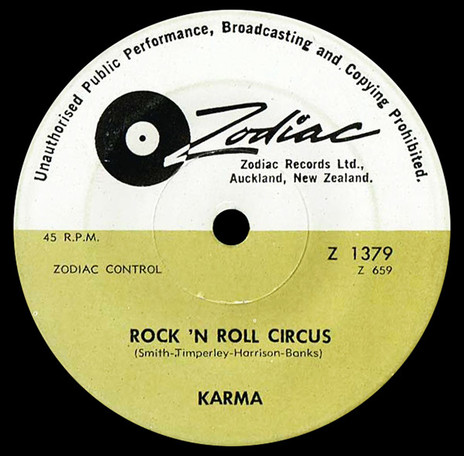

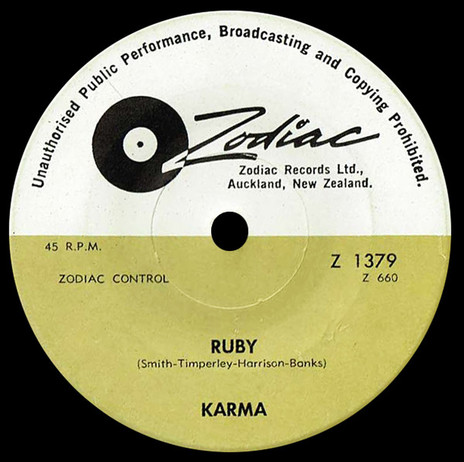

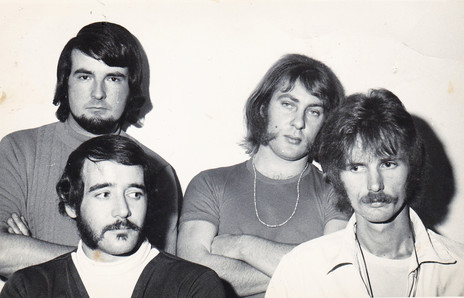

Karma had four different bass players during its first five gigs

Within weeks, the new band Karma debuted there. They had four different bass players during their first five gigs and were left stranded one night until a Granny’s waitress offered up her boyfriend who had just returned from Australia and was sitting at home doing nothing.

She rang him and minutes later in strode the bespectacled John “Yuk” Harrison, late of Max Merritt & The Meteors and Levi Smith’s Clefs, already a local legend and session man on a multitude of New Zealand tours and recordings.

Harrison became a permanent member and very quickly bestowed the others with nicknames. Johnny Banks became JB, Peter Timperley was rechristened Cockerel for the way he strutted around the stage and the approachable Bob Smith was Captain Social or just Captain – a name that would stick for most of his career.

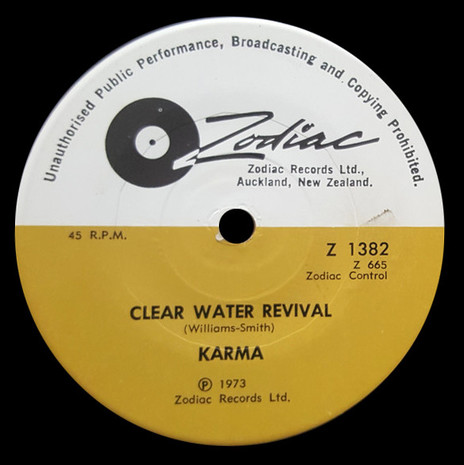

Karma released three singles on Zodiac in the early 1970s and toured the country with Headband, Ticket and Corben Simpson. Their final performance was at The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival in January 1973, where Harrison’s increasingly wild behaviour culminated with him going nude while the band backed Shane on his hit song ‘St Paul’.

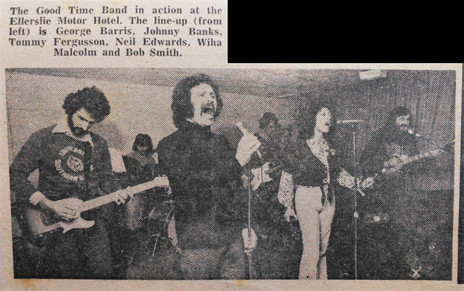

Smith kept busy in Auckland singing and playing on jingles, and on albums by The Human Instinct, The Rumour and others, sometimes adding his mother’s maiden name to be credited as Robert Hooper-Smith. He was enticed away to follow Karma drummer Johnny Banks in joining Tommy Ferguson’s Goodtime Band, then based in Hamilton and including former Underdogs Neil Edwards and George Barris.

After that wound up, Smith joined the comical Peter Caulton in Distillery working the NZ Breweries circuit. Distillery toured in support of jazz-pop cabaret singer Ricky May and a few weeks later Smith answered an SOS call from Wellington where the pick-up band was struggling with May’s material. To get the job done, NZ Breweries flew Smith and former Invaders Dave Russell and Jimmy Hill to the capital.

The night before the gig, Smith ventured to the Entertainers’ Club where former Quincy Conserve member Denys Mason was blowing saxophone in a hot band. Their keyboard player, Rufus Rehu, was unavailable but his instrument was onstage and Smith was invited to sit in. When the floorshow act turned out to be Sonny Day, Smith hid until the chorus of opener ‘Johnny B. Goode’ before surprising his one-time Dallas Four bandmate by playing along.

The show with May at the St George Hotel was a huge success and May enlisted Smith to find a rhythm section in place of the unavailable Russell and Hill for the remaining run of gigs in New Plymouth and Tauranga. Smith called on his ex-Distillery cohorts Paul Davies (drums) and Rick Adcock (bass) who had watched the May show night after night while the two bands toured together.

Smith returned to Distillery and arranged and recorded their entry in the heats of Studio One’s New Faces talent quest in 1974. That same weekend he was invited to join the band he had jammed with at the Entertainers’ Club. Owner Ray Johns was revamping the venue, Rufus Rehu was departing and the guys were keen to add Smith.

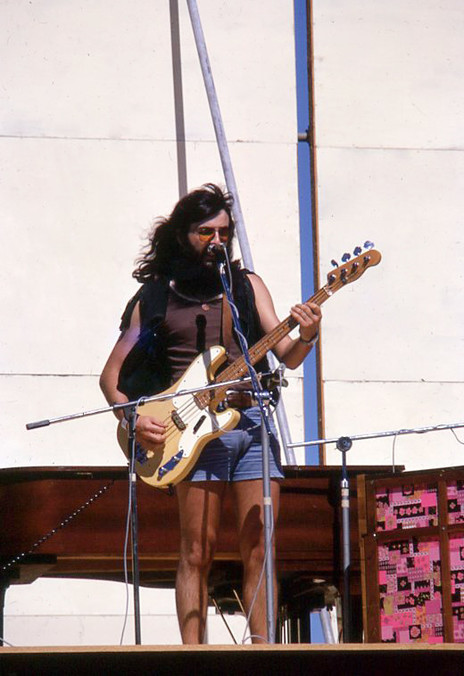

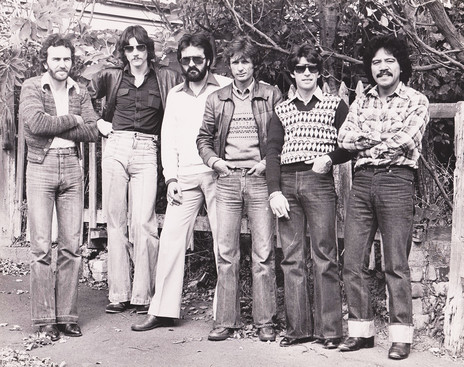

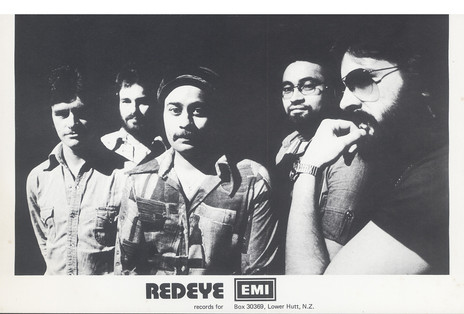

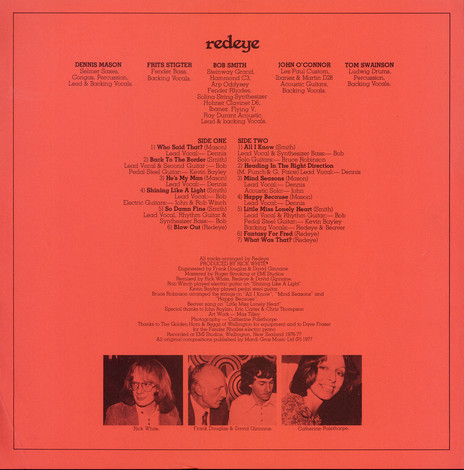

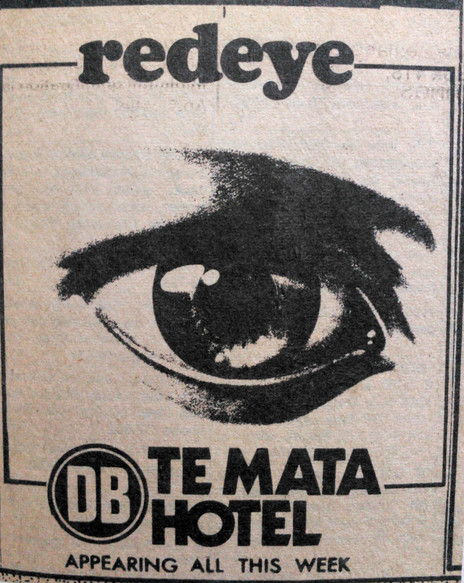

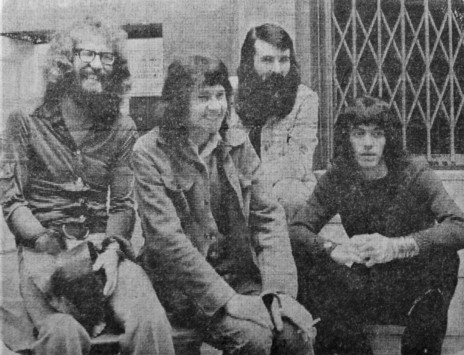

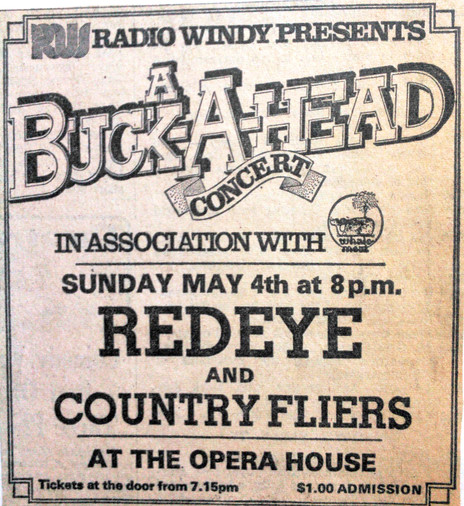

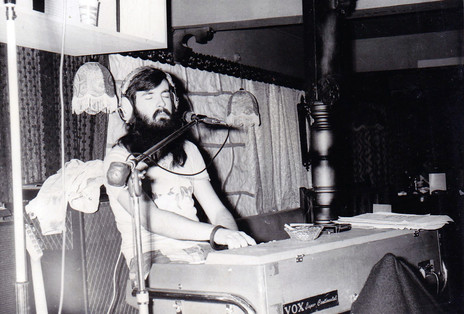

So he packed his entire life and belongings in the back of a Hertz Ford Transit van and moved in with Johns for a period. By the time the club reopened as the Western-themed The Cabin in September, the band had renamed itself Redeye, as in the Wild West whiskey, with a line-up of Smith, Denys Mason, drummer Tom Swainson (ex-Tom Thumb), bass guitarist Frits Stigter (Timberjack, The Quincy Conserve) and guitarist John O’Connor (Supernatural Blues Band).

Smith says that, looking back, Redeye is the best band he ever played in.

“It was a private club, so a lot of the same people every week,” Smith said. “We did some really interesting stuff and [it was] a really great band. I would have to say probably, looking back for me, that’s the best band I ever played in, for sure.”

Redeye was strong on Stevie Wonder and Bill Withers and obscure album tracks that most of the audience came to believe were their own. Musician Andy Anderson had turned them on to Dr John’s Desitively Bonnaroo, which opened their ears to The Meters and Allen Toussaint and gave the band a whole new repertoire.

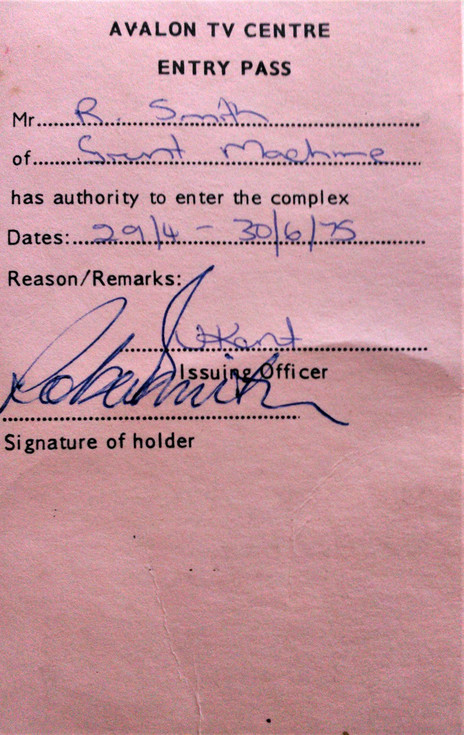

It didn’t take long for Redeye to build their reputation. Within six months, TV producer Mark Westmoreland engaged them as resident backing band for the local artists on new music show Grunt Machine. When Ready To Roll went to air in the middle of the year, Redeye could again be seen behind New Zealand singers such as Steve Gilpin, Craig Scott, Tina Cross, Steve Allen and Kim Hart.

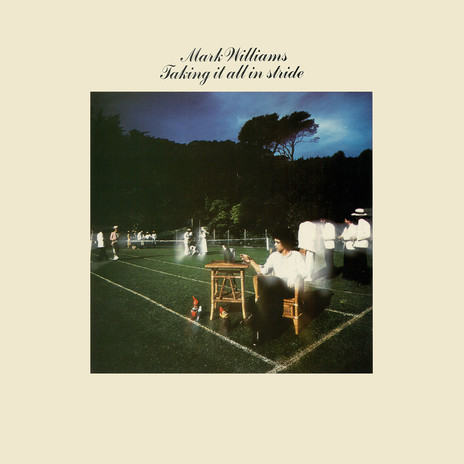

They were also frequenting the capital’s EMI Studios, sharing session work with Rockinghorse on the first two Mark Williams LPs before featuring entirely on his third, Taking It All In Stride. And they were the band on John “Timberjack” Donoghue’s 1975 Donoghue album.

During a break in 1976, Smith spent six weeks with his dad and brother in England, taking time to catch up with old mates Chris Thompson, Billy Kristian and Mike Walker, who were all based there.

Redeye reconvened in Christchurch for a week “to get our shit together” at one of Trevor Spitz’s clubs. While there, tales of “a suspicious package” being left at their Wellington gig The Cabin made the national news and the band decided they would not go back there.

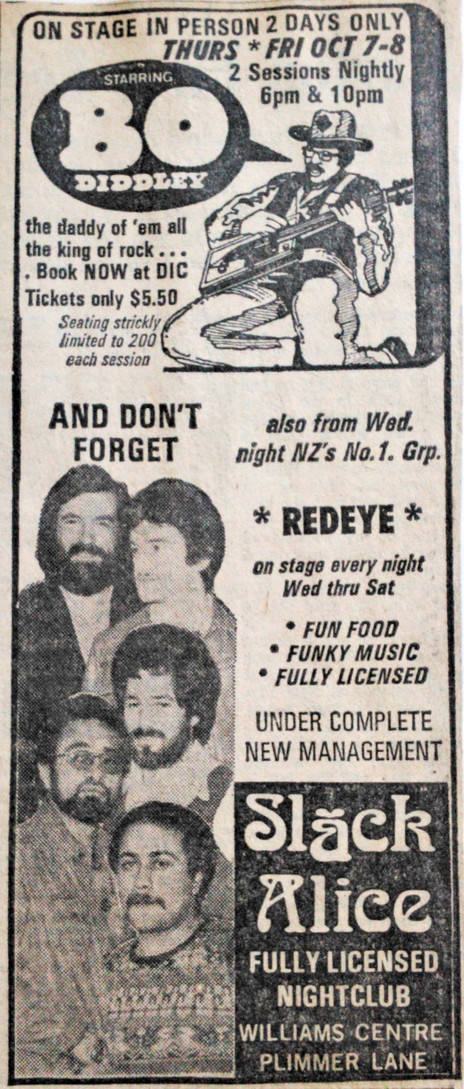

When they told Spitz about it that night, he confided his boss Phil Warren was looking for a resident band for his new Wellington nightclub Slack Alice. Redeye took the gig but it was a more poppy affair than what they were used to and – not long after it was renamed Nightsite and then Exchequer – they did return to The Cabin.

For the opening two weeks at Slack Alice the guest artist was American guitarist Bo Diddley, whose “rehearsal” consisted of calling Redeye to his dressing room and saying, “Y’all know my riff?” They did. “I play all my songs in E. Oh, I’ve got one in G … and one in A. So, how’s it going?”

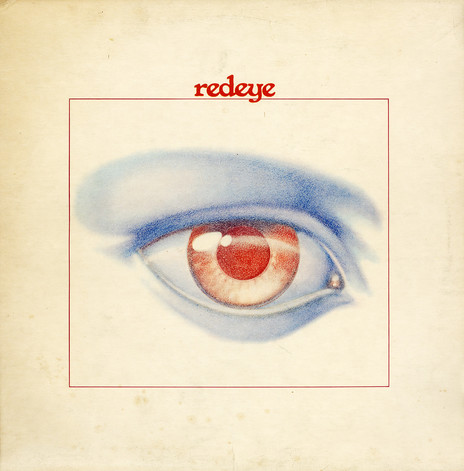

Redeye released three singles on EMI – ‘Who Said That?’ (1976), ‘He's My Man’ (1977) and the Smith-penned ‘Little Miss Lonely Heart’ (1977) – and a self-titled 1977 album, all with producer Rick White, who was formerly in Tom Thumb with Redeye drummer Tom Swainson.

Smith: “When we were offered the opportunity of doing an album we went, ‘Do we really want to do this?’ And we said, are we just gonna do covers like we normally do or are we gonna try and write some stuff? And Denys said he wouldn’t mind trying to write some stuff and we decided to do a bit of both, so Denys and I were the two who went away to write things.

“In the end it was this weird collection of stuff, to be honest. We did one or two covers – we did a couple of Bill Withers things – and the album got released and it didn’t do anything because we weren’t in a position to do anything. It was a wasted opportunity.”

The 1977 ‘Redeye’ album was “a wasted opportunity,” says Smith

Smith put a lot of thought into his decision to quit Redeye in mid-1978 after a phone call from Chris Thompson in England. Fresh from fronting Manfred Mann’s Earth Band on their US No.1 ‘Blinded By The Light’, Thompson wanted Smith to join a band of New Zealanders he was putting together in London.

“I loved playing with Redeye. We’d been playing so much together over that reasonably short period of time that the telepathy between us was just extraordinary.” But after talking to his bandmates, it dawned on Smith that although Redeye was his first big-name group, the others might not hold the band in quite the same high regard he did. So he flew to England, joining Thompson, Mike Walker and Billy Kristian in Filthy McNasty.

Outside influences contributed to Smith’s tenure not working out and he left before the band had evolved into Night and scored a US hit with ‘Hot Summer Nights’. Smith stayed in London working in a bar and a warehouse before returning to New Zealand with a tape of demos from a publishing contact at Chrysalis Records.

Back in Wellington in early 1979, he ran into A&R man Danny Ryan who was looking for material for his new protégé Jon Stevens. Smith handed over a handful of the Chrysalis songs including ‘Jezebel’ by Brummie songwriter Eddie Howell. It would be a No.1 hit for Stevens.

Having played keys on Larry Morris’s 1976 album Reputation Don’t Matter Any More, Smith moved to Auckland in 1979 to join Morris’s super group Shotgun. The line-up was helmed by Morris’s right-hand man and Smith’s former Dallas Four bandmate John Kristian on guitar and also included John Parker on guitar, Bob Jackson on bass and Billy Nuku on drums.

Shotgun set up base at Mascot Recording Studios and released the single ‘Taste Of The Devil’ on Vertigo, but by the end of the year they were no more. The diverse, intense personalities could be hard going and their slightly outdated material was out of step when sharing the same bills as Midnight Oil, Sheerlux and the like.

Smith returned to Wellington in time to be added to the band for Sharon O’Neill and Jon Stevens’ high-grossing national tour. He resumed working with his Redeye compadre Denys Mason and recorded demos for Stevens to take to Australia to secure a deal.

There, Stevens was signed to Big Time and went to the United States to work with producer Trevor Lawrence. The only song retained from the demos was ‘Running Away’, a song Bob Smith had written in his spare bedroom in Hataitai. It was cut in Los Angeles with the cream of the city’s studio players, including Toto guitarist Steve Lukather, drummer John Robinson and bass guitarist Nathan Watts, and released on Jon Stevens.

In 1981-82, Smith spent six months on the road with Sharon O’Neill’s Australian band and was intending to settle in Sydney after fulfilling a commitment to TVNZ for a second series of light entertainment show Rock Around The Clock. At the same time he played on the Jim Hall-produced Dennis O’Brien LP Strangers. Upon its completion, Smith called O’Neill to be told if he had work in New Zealand he should stay there because there was little on offer in Sydney.

For the remainder of the 1980s, he was in demand singing and playing on jingles, TV sessions and records, including albums by Eddie O’Strange, Jodi Vaughan, Netherworld Dancing Toys and Tex Pistol, aka Ian Morris. In 1985 he came across the Bruce Springsteen song ‘Saving Up’ on a Clarence Clemons album, and recommended that his friend Sonny Day record it; the song became a radio favourite and revived Day’s career. In 1987 Smith was part of the slick backing band for the ill-fated country music TV show Dixie Chicken, which was pulled from the air after only one episode.

In the 1980s Smith was in demand singing and playing on jingles, TV sessions and records

Jon Stevens’ brother Don Stevenson lured Smith back to the live scene in the early 1990s when he brought together a Commitments-style outfit called Soul Patrol to play at the Metro nightclub. Most of the jingle work headed to Auckland and Smith took a day job and drifted in and out of covers bands, including a spell with Darren Watson’s post-Smokeshop line-up The Hot Left Overs.

Although he’s continued writing songs and occasionally lyrics for friends, Bob Smith plays more infrequently these days. “The attraction that began all those years ago still keeps me inspired and creative, and maybe you can't ask for more than that.”