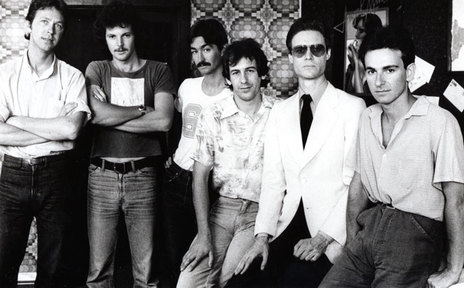

His association with that band harks back to the days after their 1980 split when he was a session musician on Graham Brazier’s Inside Out, recorded and gigged with The Legionnaires and Dave McArtney and briefly joined a revamped Coup D’Etat with Harry Lyon – all before he produced the Hello Sailor comeback The Album in 1994.

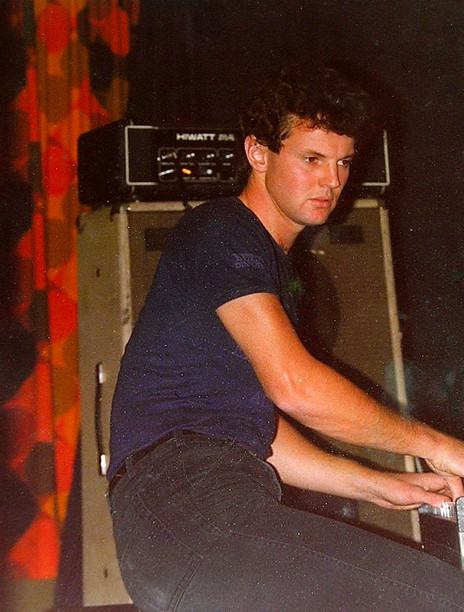

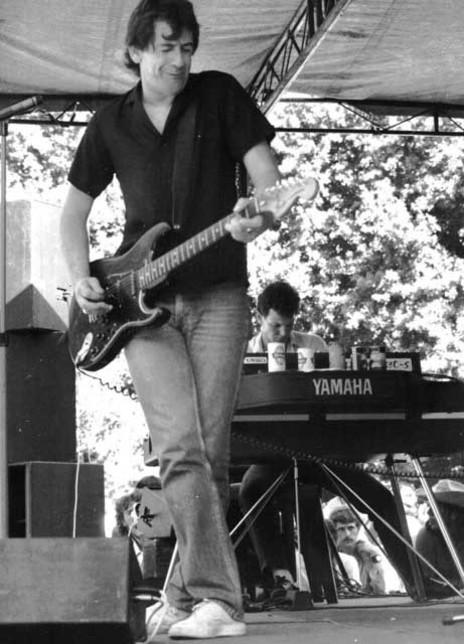

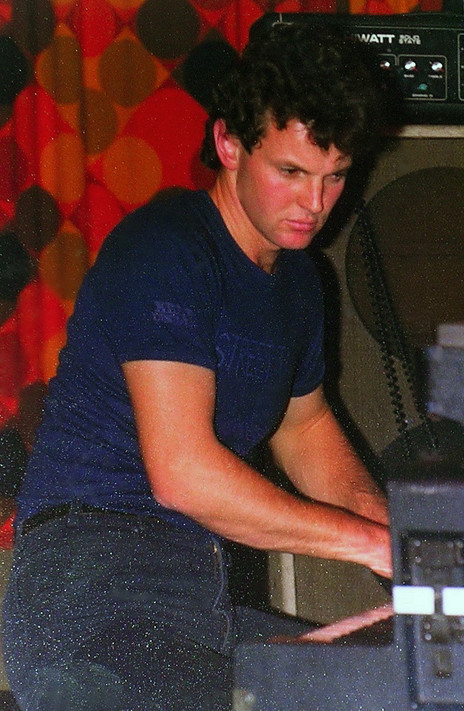

Throughout the mid-1970s while in nightclub bands led by Al Hunter and Sonny Day, Pearce carted upright pianos on mattresses under waterproof covers on hired trailers, or on dollies from one Queen Street nightclub to another. The Yamaha electric grand changed all that in 1980 and he could finally move his gear on his own.

For Years, Pearce carted upright pianos on mattresses under waterproof covers on hired trailers.

After basing himself at Mandrill Studios and serving stints in Street Talk, Hammond Gamble Band and Coconut Rough, Pearce took off to Australia where he became a partner in a studio in Sydney producing or remixing recordings by Hunter, Upper Hutt Posse, Moana and The Moahunters and ex-Easybeats frontman Stevie Wright.

Returning to New Zealand in 1991, he rejoined Mandrill until its demise and helped set up York Street Recording Studios. He produced a young Shihad, toured with Matty J & The Soul Syndicate, fell for Latin music, made a video compact disc of traditional Māori waiata for karaoke and recorded in Los Angeles with American Idol runner-up Adam Lambert.

Then there was the time Pearce was in Chuck Berry’s backing band for an Auckland show, in 1978: Berry got paid and skipped the country before the last show. More recently, Pearce and John Rowles toured with Elvis Presley’s Las Vegas-era band and they refused to play Rowles’ ‘Hush… Not A Word To Mary’ because it was a cheating song and they didn’t approve.

How interesting could a non-singing pianist be? Read on.

Leslie Pearce had been playing piano accordion and piano in dance bands around South Canterbury for around 15 years by the time his son Stuart was born in Timaru on 27 January 1956. The youngster’s grandmother played the church organ and at home Stuart would play the piano accordion, piano, melodica and drum kit while the radio blared the latest hits of Marty Robbins and Helen Shapiro.

By the time Stuart was about seven, his father was taking him from their Albury home for weekly piano lessons in Timaru. When the Pearce family sold the farm and bought another in Wellsford, north of Auckland, lessons continued with teacher Glenda Grant until Stuart was 15.

By that time he was often taking the bus to Auckland, for films such as Woodstock, Gimme Shelter and Mad Dogs & Englishmen and concerts by Elton John, Led Zeppelin and Mungo Jerry.

“And I just thought, ‘This is what I’m gonna do. I’m gonna get into a band,’” he told AudioCulture. “And I said to my parents, ‘Can I go to Auckland and join a band?’ And they said yes, and I got the shock of my life. So I did.”

He spied an ad in the NZ Herald for a piano player for a nightclub residency. The band was Chapeaux, led by former Cruise Lane frontman Alan [Al] Hunter. His audition was a success and he stayed with Chapeaux for two years, playing at Phil Warren’s The Crypt and in 1974 supporting Rod Stewart & The Faces and Leon Russell, both at Western Springs.

Martin Winch was guitarist for Chapeaux when Pearce joined, but not for long. “Martin Winch was the very first guitarist I ever played with. How lucky was that? Although I had studied piano and theory for years, there was never any naming of chords taught to me. Everything was notes and fingering. Within two weeks Martin had taught me every chord voicing I would ever need for the rest of my life, the whole damn lot.”

Red McKelvie, a good mate of Hunter’s, caught Chapeaux with their new member and put Stuart Pearce’s name forward to former Underdogs singer and burgeoning jingles writer Murray Grindlay as a possible sessions prospect. There was work aplenty for Auckland’s piano players and the phone started ringing constantly.

“The piano players who were here in Auckland when I came down as a kid – my absolute heroes – were Spike [Mike] Walker, who was playing at Granpa’s, and Carl Doy, who was playing in another one of Phil’s clubs called the Ace of Clubs,” Pearce said. “Carl Doy was the resident piano player up there, just around the corner from us at The Crypt. Peter Woods was playing jazz, and the other incredible piano player was Crombie Murdoch.”

When Sonny Day’s Caravan replaced Chapeaux at The Crypt, Day invited Pearce to stay on, joining a line-up that included former Invaders Jimmy Hill on drums and Dave Russell on bass. He didn’t stay long however, after saving enough cash to embark on his OE.

Besides taking in Europe and North Africa, he hunkered down in London and scanned the pages of ads in the NME and Melody Maker asking for a keyboards player “for group about to record an album and tour”. He quickly learnt that if the voice at the end of the phone instructed to leave your instrument at home it was just a record company manufacturing a pretty band.

Two years after he arrived in London, Nearly every young band had spiky hair, safety pins and leather bondage gear.

During his two years there he played in three or four English pub-rock bands paying five quid a night per member. “I think we got as far north as Leeds one night; drove all the way to Leeds to do our £5 gig,” Pearce laughed. “I thought the money was horrendous because I was keen to get back to Auckland and get back to my $110 a week nightclub residency!”

By late 1977 nearly every young band in London had spiky hair, safety pins and leather bondage gear, while Pearce was searching out a slick, tight band to join. “Music magazines were all about Rick Wakeman, Patrick Moraz and Keith Emerson. The virtuosos dominated. This explains the punk phenomenon – at least teens could have a good time.

“I was there right through the punk years. I witnessed the whole thing and it was pretty funny. Then I had to come back and watch the Kiwi version of it repeat itself two years later!” Before that, however, Pearce was recruited into the band on board the Australis and stayed on for a couple of round trips until he finally journeyed home.

Back in Auckland, he found Sonny Day still resident at The Crypt and took back his place behind the piano. “It was almost like I had never been away,” he said. “I went away for two years, jumped back into the same band and after one week thought, ‘Shit, did I imagine that?’” He also discovered the city’s formidable pianists were busy in the jazz area, so he decided to concentrate on everything else.

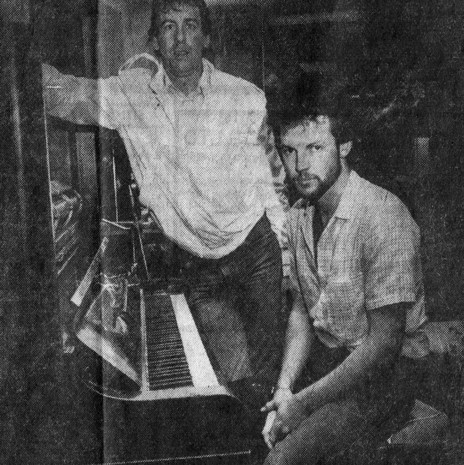

Work began pouring in and one day at a session at Mandrill, Pearce heard the dubbing engineer was leaving. He applied to owner Glyn Tucker and was given the job. Being the junior engineer meant whenever a client needed a pianist they only had to poke their head around the corner.

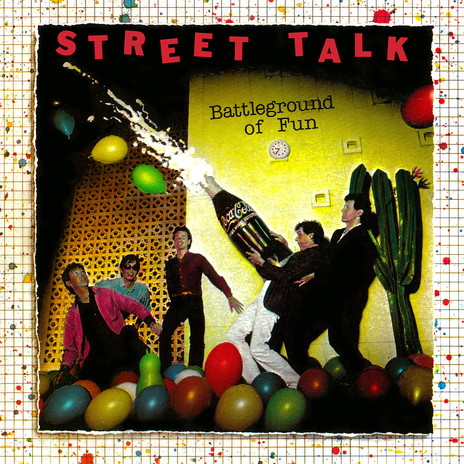

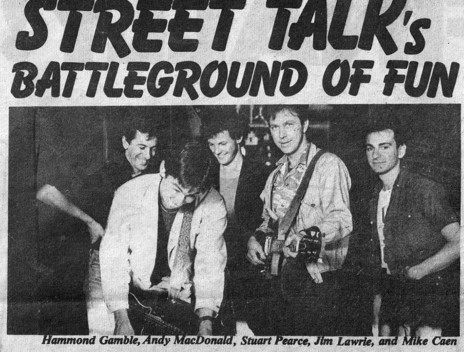

That’s exactly what happened when larger-than-life American producer Kim Fowley landed in Auckland in January 1979 and announced he would produce a Street Talk album at Mandrill. He declared, “Bruce Springsteen’s got a piano player, you guys have gotta have a piano player.”

“And so I was inflicted upon Street Talk,” Pearce said. “I think Hammond was the only guy who kinda liked what I was doing, actually. The others were all like, ‘What the fuck?’”

For almost two years Street Talk rotated with Th’ Dudes and Hello Sailor around Auckland’s major pub venues – The Gluepot, The Windsor Castle and the Station Hotel – with the occasional trip to Hamilton, Whangarei, Wellington or Christchurch.

At the conclusion of the Auckland pub bookings at 10.30pm, Pearce would grab his synth from atop the piano, jump in his car and shoot off to nightclub gigs with the likes of Larry Morris, Fantasy (featuring future Herbs guitarist Dilworth Karaka), Human Instinct, or an early version of The Pink Flamingos. The nightclub would be dead when he arrived, but by the time the band started at 11pm the place would be heaving.

When Street Talk was out of town, Pearce sent along a fill-in pianist of the ilk of Murray McNabb or Peter Woods to play his club gigs. “Because piano players are good like that, we all keep each other’s seats warm. Sometimes you’d fill in at a nightclub for a month for someone.”

Pearce’s later fling with Harry Lyon’s Coup D’Etat – a year after the chart success of ‘Doctor I Like Your Medicine’ – was just another nightclub residency. “That’s just me saying, ‘Oh, here’s a club gig, three nights a week. I’ll go and do that one.’

From 1982, three things killed the Auckland nightclub gigs: home videos, drink-driving blitzes, and the casino.

“Like most musicians from the 70s, I kinda thought that those nightclubs would never end. We thought, ‘Wow, this is incredible! This will go on forever.’ But there were three things that killed those nightclubs from 1982 onwards – home video players, the drink-driving blitzes and then when the casino opened. See ya later, nightclubs with resident bands.”

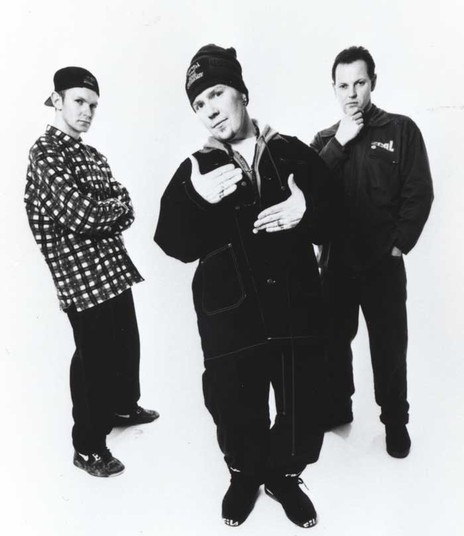

Street Talk split in half towards the end of 1980 with Pearce choosing The Hammond Gamble Band over the Mike Caen-fronted Blind Date. He appeared on Gamble’s self-titled solo album, receiving a co-write with Gamble and Kim Fowley on ‘Should I Be Good Or Should I Be Evil’.

For a time, Gamble and Pearce went around Auckland as a duo “playing excruciatingly loud”. One weekend their manager, Brian Jones, engaged as their support act a pair of girls he’d found busking at his Cook Street Market.

“Afterwards we had to say to Brian, ‘Mate, they are too good. Can you get rid of them?’ Rule number one in the rock’n’roll handbook is never form a trio with a married couple, rule number two is never, ever try to follow The Topp Twins.” But Pearce would go on to feature on many of the Topps’ recordings over the ensuing years.

In 1982, he was an arranger and keyboards player on Prince Tui Teka’s album The Man, The Music, The Legend, produced by Dalvanius and Barletta Prime. Its single ‘E Ipo’ was No.1 for two weeks that July.

ANdrew McLennan wanted to know if Pearce was interested in joining his new project, Coconut Rough.

The following year, he got a call from Andrew McLennan (aka Andrew Snoid) who was back in New Zealand after a spell with The Swingers in Australia. McLennan wanted to know if Pearce was interested in joining his new project, Coconut Rough. “He asked if I wanted to play in a sort of a poppy band and the idea really appealed to me.”

With former Blam Blam Blam guitarist Mark Bell also on board, Coconut Rough signed with Mushroom Records and released their debut single ‘Sierra Leone’. Driven along by Pearce’s Toto-inspired keyboard vamp, it peaked on the New Zealand charts at No.5 in September and went top 50 in Australia.

The producer was Dave Marett, an Australian who had previously produced or mixed New Zealand acts Dragon, Sharon O’Neill, Mi-Sex and The Tigers in Sydney. Mushroom also had Marett produce the Dance Exponents’ debut LP Prayers Be Answered, for which he had Pearce redo the piano parts with the instruction, “Listen to this piano and play it exactly the same, except tight.”

About two months after ‘Sierra Leone’, Pearce was enlisted to work on Dalvanius Prime’s groundbreaking ‘Poi E’. Released by the Pātea Māori Club early in 1984, ‘Poi E’ was everywhere during the first half of the year and held the No.1 spot on the singles chart for four weeks from March 18.

“The beat was based on the Stevie Wonder-Jackson 5 hit ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’, but of course that record is more complex in its detail,” Pearce recalled. “Dal had heard this song played loudly at a function in Pātea, and he heard the stamping of the local Māori party crowd. So, his main instruction – and repeated-many-times catchphrase – for ‘Poi E’ production was ‘Hobnail boots! I want to hear those hobnail boots stomping! More boots!’ He kept this instruction up all the way through mixing too.”

Meanwhile, Coconut Rough’s fortunes had taken a dive. With The Narcs they shared a Radio With Pictures live-at-Mainstreet LP, Whistle While You Work, but their own self-titled album met delay after delay with Mushroom in Australia. A week after debuting a new rhythm section that included ex-Swinger Bones Hillman, Pearce left.

He was tempted away by the offer of a month-long tour of Texas with That’s Country stars Gray Bartlett, Brendan Dugan and Jodi Vaughan. Coconut Rough was released during his absence and when he got back he accepted a nightclub residency with the nine-piece 42nd Street at Club New York in old Papatoetoe.

Although he started producing jingles in 1980, Pearce produced his first album in 1985 with Anne Dumont’s Feeling The Distance on Epic. “The first album I produced for Anne Dumont, we set out to make an ABBA-type record. So, that’s how long I’ve been an ABBA fan. They hit my ears at the first chord change in ‘Waterloo’ when I heard that flatted fifth used like that in the melody.”

Pearce relocated to Australia in 1986. He took up with Sydney band Girl One and when the band went in to Transistor Music to record a single he was surprised to find the producer was Coconut Rough producer Dave Marett.

He and Pearce set up the eight-track digital recording studio Greystoke Music at Marett’s home in Wheeler Heights. Marett took his overflow work there while Pearce basically ran proceedings. Former Ticket guitarist Eddie Hansen’s studio was just up the road and he and Pearce would work on each other’s stuff.

One of Pearce’s earliest clients was Al Hunter, the man who had given him his big break when he moved to Auckland. Hunter had returned to his first love, country music, and arrived with a budget from CBS for a single. Pearce stretched the money into Hunter’s acclaimed debut long-player, Neon Cowboy. “I probably wanted to say thanks to Al for getting me started actually. I thought, ‘Gee, I owe this fulla something,’ so I poured my heart into that.”

In the late 80s, Southside label boss Murray Cammick began using Greystoke to remix his artists’ recordings. One such act was Moana and The Moahunters; another was Upper Hutt Posse, who stayed with Pearce while they worked on ideas. The brief from Cammick was, “Make a new version, hopefully one that is more danceable and fun.”

“With mostly approval from Upper Hutt Posse, I remixed and reprogrammed three tunes – ‘Do It Like This’, ‘That’s The Beat’ and ‘Stormy Weather’. With an Akai S900 sampler I could sample beats from other records to create the desired effect,” Pearce said.

A fill-in stint in Dragon led to a three-month Australian tour as part of dance band The Rockmelons, then fronted by Deni Hines. Promoted by Grant Thomas (Crowded House), with The Models as support, the tour started in Darwin and ended at the Auckland Town Hall. Along the way they hung out with Simply Red, who were on their own tour.

When Glyn Tucker offered him a chief production job at Mandrill in 1991, Stuart Pearce returned to Auckland, although he would continue commuting to Sydney till the end of the decade to work for Dave Marett. He remained at Mandrill until its closure in 1993 and then helped set up and suggested the name for York Street Studio just across the road.

The first recording made there was a contra deal for artist manager George Hubbard, who organised a traditional Māori opening for the place. “George says, ‘Yes, I can do that for you, but in exchange I want you to give me one free day in the studio for one of my acts,’” Pearce recalled. The day after the opening party, studio partner Jaz Coleman, of UK post-punk outfit Killing Joke – and Pearce’s flatmate – produced Emma Paki’s ‘System Virtue’.

Pearce spent about a year sequencing and working on songs with R&B/soul singer and rapper Matty J. Ruys. When it came time to road test the material, Pearce approached promoter Gray Bartlett, who added them to Ruby Turner’s New Zealand dates. They drafted Paddy Free and named themselves Matty J & The Soul Syndicate.

In 1994 Hello Sailor reconvened at York Street with Pearce on keys and in the producer’s chair.

“We had a whole album ready to go, but at the very last minute Matty J basically dropped me and got his album produced by Mark Tierney from The Strawpeople – listening to the tracks I’d done up and getting a band to play them. And then they got my version of ‘Colour B.L.I.N.D’, which was the only one that I’d actually finished and mixed properly, and unbeknownst to me stuck it on the record!”

In 1994 Hello Sailor reconvened at York Street with Pearce on keys and in the producer’s chair to record The Album. “I’d done The Legionnaires and I’d done The Flamingos and I’d even played in Coup D’Etat, so I had a connection with all three guys, and so I think they just asked me to play with them. I started playing with them live because I’d played with them a lot.”

Having produced Latin band Kantuta, Pearce became fascinated with percussion. While based at Greenstone Music in Karekare, he and Nick Tracy formed an experimental band built around Pacific beats and log drums. They played the first NZ Womad in 1997 where Japanese singer Monta Yoshinora asked Pearce to do an album with him in Osaka, but it was never completed. Pearce followed that up with six months in Dubai in 1999 as part of Kantuta before setting up a home studio in Auckland.

At the invitation of former York Street partner Malcolm Welsford, Pearce spent time producing and arranging in Los Angeles in 2005 and 2006. The first trip was for two CDs based on the 1950s Eloise children’s books written by Kay Thompson and illustrated by Hilary Knight. “I got Hammond Gamble to write all those songs, actually,” Pearce said. “He knocked them all out really quickly.”

The second included charting and arranging demos sung by unknown singer Adam Lambert with Madonna’s guitarist, Monte Pittman. The recordings came to nothing until Lambert was riding high on the American Idol TV show three or four years later and they were released as the unofficial album Take One. It sold 48,000 units and incurred all kinds of legal threats.

By that time Pearce had served as bandleader and arranger on TV series Pop’s Ultimate Star and musical director on New Zealand’s Got Talent. In 2009 he joined The Mermaids Dance Band as musical director; it featured singers Pauline Berry, Amber Claire and former TrueBliss singer Joe Cotton.

In 2011, a month after being inducted into the NZ Music Hall of Fame as part of Hello Sailor, a local music magazine puzzled why an old Sailor was playing with trendy young band Home Brew. “They [the magazine] really made me feel embarrassed,” Pearce said. “I thought it was ageism. Tom [Tom Scott] said, ‘Come and help us at this gig, Stu. No money. It’s easy though; just play these seven or eight songs.’ ‘Okay, sure.’ The little shits never told me there would be a video and sound production crew there filming the Red Bull Sessions.

“When I go along and get this Sailor award, nobody knows me. There’s only a few bands know me, and a few singers. Nobody knows me in the public arena. And as soon as we got that award, I felt like I got slapped in the face because I was playing with Home Brew, because basically Home Brew were the flavour of the month right at the same time.”

The truth was Pearce had recorded Home Brew rapper Tom Scott at his home studio long before Scott formed his own band with his dad Peter Scott on bass. “Pete and myself sort of mucked in to help assemble the first line-up, and within months they were taking care of themselves. I flicked Home Brew miscellaneous tracks for a long time and never had the heart to charge them for my services. Who would? I was happy just observing.”

Stuart Pearce has existed as a versatile, non-singing pianist for more than 40 years. He estimates he has played a minimum of 9,000 gigs, most of those in covers bands.

“It's very hard to estimate as I was playing clubs and bars solidly from 1973 until 2004. That is an average of five gigs a week, for decades I was playing 10, sometimes more. Now I still play 50-100 gigs a year, but an exact figure over 46 years is impossible to know. But to survive well I always accepted offers from the busiest groups – the resident bands.

“As a musician there is a certain stigma around being in a covers band, but I will say this: when music is being played by people, not one person onstage is thinking about who wrote it. Most of my recording work has been original Kiwi songs; most of my live work has been covers. A recording pop band may play 25 times year, a nightclub band may play 250 times. I did both simultaneously.”

--

Read more: Stuart Pearce, the piano has been thinking